This repository contains common methods for encoding and generating spikes.

Install via pip

pip install spike-encoding

NOTE Requires python >= 3.10 (!)

NOTE This will also install torch and torchmetrics

You can import it like any other package. For instance, you can import the StepForwardConverter as follows

from spike_encoding.step_forward_converter import StepForwardConverter

NOTE There may be compatibility issues with prior versions. If you are upgrading to a newer version, please use

pip uninstall spike-encoding

and install it again. If you install the newer version without uninstalling, there may be strange errors.

The repository provides common methods of encoding scalar values to spike trains. In many cases there is also an inverse method that decodes spike trains back to scalar values. The current implementations include

- Ben's spiker algorithm (BSA)1 - Encoding, Decoding & Optimization

- Step-forward encoding (SF)2 - Encoding, Decoding & Optimization

- Pulse-width modulation (PWM)3 - Encoding, Decoding & Optimization

- LIF-based encoding (LIF)4 - Encoding, Decoding & Optimization

- Gymnasium encoder5 - Encoding

- Bin encoder6 - Encoding

For each encoder, there are examples on its usage in the examples folder. In general, encoders are created by creating an instance of its class and then calling its encode method. Optionally, parameters can be given or determined through and optimization method.We will see this in more detail in the following sections.

There will be some utility for loading datasets. Right now, only Spiking Heidelberg Digits is supported (https://zenkelab.org/resources/spiking-heidelberg-datasets-shd/). You can load it as follows:

from spike_encoding.datasets import load_processed_shd

loaded = load_processed_shd(100)BSA1 encodes signals into spikes by using a combination of FIR (Finite Impulse Response) filtering and error comparison. For each timestep, it compares the error between the signal and a potential spike's filter response. If adding a spike at the current timestep would reduce the overall error by more than a threshold amount, a spike is generated and the filter response is subtracted from the signal. This process continues for each timestep, effectively encoding the signal into a series of spikes that can later be decoded by applying the same FIR filter to the spike train.

The method has three main parameters that can be optimized:

- Filter order: Controls the length of the FIR filter

- Filter cutoff: Determines the frequency response of the filter

- Threshold: Sets how aggressive the spike generation should be Here we will illustrate this with a simple hardcoded signal.

We will illustrate its usage with a simple hardcoded signal.

import torch

signal = torch.tensor([[0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0, 0.9, 0.8, 0.7, 0.6, 0.5]])Then to encode the signal, we do

from spike_encoding.bens_spiker_algorithm import BensSpikerAlgorithm

bsa = BensSpikerAlgorithm()

spikes = bsa.encode(signal)

# returns [0., 1., 1., 0., 1., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.]And to decode the spikes again, we can simply call the decode method

reconstructed = bsa.decode(spikes)

# returns [0.5, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5, 0.82, 0.87, 0.80, 0.72, 0.62, 0.53]

# NOTE these outputs were rounded for easier displayingThe implementation also supports optimization of the parameters for a given signal. This is achieved by calling the optimize method.

filter_order, filter_cutoff, threshold = bsa.optimize(signal)These parameters can then be used to create an optimized instance of the BensSpikerAlgorithm.

bsa = BensSpikerAlgorithm(threshold, filter_cutoff=filter_cutoff, filter_order=filter_order)SF2 encodes signals into spikes by comparing signal values against an adaptive baseline plus/minus a threshold. For each timestep, if the signal value exceeds the baseline plus threshold, an "up spike" is generated and the baseline is increased by the threshold amount. Similarly, if it falls below the baseline minus threshold, a "down spike" is generated and the baseline is decreased. This adaptive baseline approach creates two complementary spike trains that can be used to reconstruct the original signal by accumulating the changes represented by each spike.

The method has one main parameter that can be optimized:

- Threshold: Controls how far from the baseline the signal must deviate to generate a spike

Here we will illustrate its usage with a simple hardcoded signal.

import torch

signal = torch.tensor([[0.1, 0.3, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 0.6, 0.7, 0.9, 0.5, 0.3, 0.2]])Then to encode the signal, we do

from spike_encoding.step_forward_converter import StepForwardConverter

sf = StepForwardConverter(threshold=torch.tensor([0.1])) # (optional parameter, default value 0.5)

spikes = sf.encode(signal)

# returns two spike trains (up/down spikes):

# up: [0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

# down: [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, -1.0, -1.0, -1.0]And to decode the spikes again, we can simply call the decode method

reconstructed = sf.decode(spikes)

# returns [0.0, 0.1, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.5, 0.4, 0.3]The implementation also supports optimization of the threshold parameter for a given signal. This is achieved by calling the optimize method.

threshold = sf.optimize(signal)These parameters can then be used to create an optimized instance of the StepForwardConverter.

sf = StepForwardConverter(threshold=threshold)PWM3 encodes signals by comparing them against a carrier signal (typically a sawtooth wave) to generate spikes. When the input signal crosses the carrier signal, spikes are generated. The frequency of the carrier signal can be optimized to minimize reconstruction error. The method supports both unipolar (up spikes only) and bipolar (up and down spikes) encoding.

The method has several parameters:

- Frequency: Controls how often the carrier signal repeats, affecting spike density (optimizable)

- Scale Factor: Scaling applied to normalize the input signal amplitude

- Down Spike: Boolean flag to enable/disable bipolar encoding (True = bipolar, False = unipolar)

Here's an example using a simple signal:

import torch

signal = torch.tensor([[0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.2]])To encode the signal:

from spike_encoding.pulse_width_modulation import PulseWidthModulation

# Create encoder with default frequency=1Hz

pwm = PulseWidthModulation(frequency=torch.tensor([1.0]))

spikes = pwm.encode(signal)

# Returns two spike trains (up/down spikes):

# up: [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

# down: [0.0, 0.0, -1.0, 0.0, 0.0, -1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]To decode the spikes back to a signal:

reconstructed = pwm.decode(spikes)

# Returns approximately:

# [0.0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.6, 0.6, 0.6, 0.53, 0.47, 0.4]The implementation supports optimization of the frequency parameter for a given signal:

frequency = pwm.optimize(signal, trials=100)

# Create optimized encoder

pwm_opt = PulseWidthModulation(frequency=frequency)LIF4 (Leaky Integrate-and-Fire) encoding treats the input signal as a current that increases a membrane potential. When this potential exceeds a predefined threshold, a spike is generated and the potential resets. Between spikes, the membrane potential decays according to a constant value. The input signal must be normalized before encoding, as neither the threshold nor the decay rate adapts to different signal ranges. This approach creates a biologically plausible spike pattern that can effectively represent temporal dynamics in the signal.

The method has several parameters:

- Threshold: Controls how much voltage must accumulate before a spike is generated (optimizable)

- Down Spike: If set to True, the neuron can also generate spikes when the value gets lower than -threshold. This is not biologically plausible, but can be useful in some cases.

Here's an example using a simple signal:

import torch

signal = torch.tensor([[0.5, 0.3, 0.1, 0.4, 0.8, 1.0, 0.7, 0.3, 0.6]])To encode the signal:

from spike_encoding.lif_based_encoding import LIFBasedEncoding

# Create encoder with default threshold=0.5 and membrane_constant=0.9

lif = LIFBasedEncoding(threshold=torch.tensor([0.5]), membrane_constant=torch.tensor([0.2]))

spikes = lif.encode(signal)

# Returns two spike trains (up/down spikes):

# up: [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

# down: [0.0, 0.0, -1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]To decode the spikes back to a signal:

reconstructed = lif.decode(spikes)

# Returns approximately:

# [0.55, 0.55, 0.32, 0.5, 0.54, 0.77, 0.59, 0.56, 0.55]The implementation supports optimization of both the threshold and membrane constant parameters:

# Optimize threshold and membrane constant

threshold, membrane_constant = lif.optimize(signal, trials=100)

# Create optimized encoder

lif_opt = LIFBasedEncoding(threshold=threshold, membrane_constant=membrane_constant)The purpose of this encoder is to convert scalar values to spike trains. I.e. if your feature is in the range from 0 to 1 and you want to encode the value 0.5, you might get a spike train as follows

[[1], [0], [1], [0], [1]]

The encoder works great with gymnasium environments. However, the documentation is incomplete. A small example is given below. For a more thorough example, see examples/example_cartpole.py.

Starting with an observation from an environment, such as cartpole. It might look like this

observation = [0.00662101, -0.02290802, -0.00224132, 0.00596699]If you want to encode it, you need to create a scaler and then the encoder.

# assuming you have gymnasium imported

cartpole_env = gym.make("CartPole-v1")

scaler_factory = ScalerFactory()

scaler = scaler_factory.from_env(cartpole_env)

encoder = GymnasiumEncoder(

cartpole_env.observation_space.shape[0],

batch_size,

seq_length,

scaler,

rate_coder=True,

step_coder=False,

split_exc_inh=True,

)Then to encode the observation, use encoder.forward as follows

spike_train = encoder.encode(np.array([observation]))Your spike_train will look something like this

[[[0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]]

[[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]]

[[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]]

[[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]]

[[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]]

[[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]]

[[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]]

[[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]]

[[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]]

[[ 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0]]]

NOTE The observation is wrapped in a list and the list was used to create numpy array. This is because the encoder supports batch processing.

If you want to use the step coder, you also need to create a converter.

converter_factory = ConverterFactory(cartpole_env, scaler)

converter, converter_th = converter_factory.generate()and create the encoder like this

encoder = GymnasiumEncoder(

cartpole_env.observation_space.shape[0],

batch_size,

seq_length,

scaler,

converter_th,

converter,

rate_coder=False,

step_coder=True,

split_exc_inh=True,

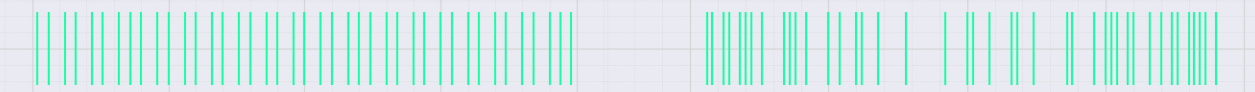

)To change the way the spikes are distributed in the spike train, use the spike_train_conversion argument. By default it is set to "deterministic". In the images below you can see it compared to poisson encoding.

What follows is an example of using the encoder with poisson encoding

encoder = GymnasiumEncoder(

cartpole_env.observation_space.shape[0],

batch_size,

seq_length,

scaler,

spike_train_conversion_method="poisson"

)Inverses of the input values may enable better predictions in low-spike count scenarios. You can set a flag to create inverse inputs.

Detailed explanation.

Let's say you are using temperatures to predict the weather. Your temperature may be between 0° and 10° Celsisus at this time of the year. When your temperature is 10°, your spike trains may look like this [[1], [1], [1], ...]. At 5° it will be alternating evenly like this [[1], [0], [1], [1], [0], ...]. Now at 0° your input will be [[0], [0], [0], ...] (always zero). Since there are no input spikes for this input, it will not trigger anything in the network. However, a temperature of 0° will have a positive impact on whether or not it may snow. Therefore you may want inputs to the contrary (i.e. not just hotness but also coldness)The encoder supports this with another flag. For every input you will receive an additional spike train with the inverse activity (high when the feature's value is low and vice versa). If you use split_exc_inh, both the positive and the negative will receive an inverse spike train (i.e. 1 scalar leads to 4 spike trains). It is used as follows

encoder = GymnasiumEncoder(

cartpole_env.observation_space.shape[0],

batch_size,

seq_length,

scaler,

spike_train_conversion_method="poisson",

add_inverted_inputs=True

)For a given firing rate of 0.9, the inverse will have a firing rate of 0.1. Inverses are appended at the end. Thus, the n inputs are doubled to 2*n, where the first n are the regular inputs and the ones that follow are their inverses.

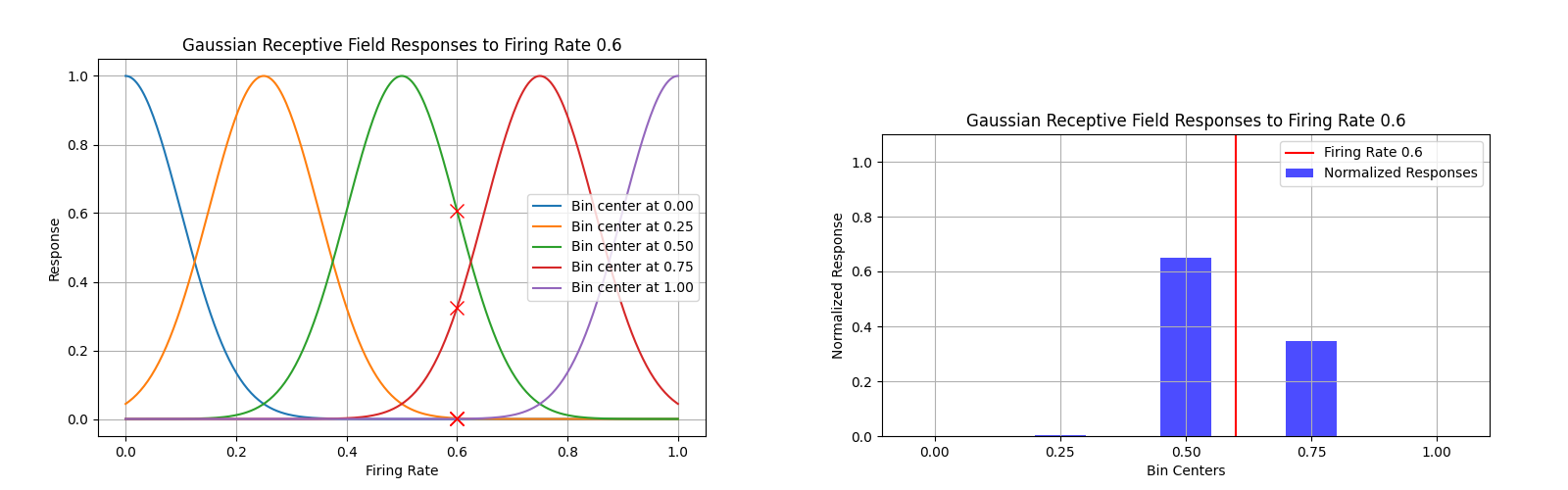

This class encodes roughly implements gaussian receptive fields. Essentially, instead of a generating one spike train, it generates a bunch of spike trains that represent how close a value is to some anchor points.

Imagine you are encoding the brightness of a pixel. It can be between 0 and 255. The encoder will first scale your input value to between 0 and 1. Now it creates a bunch of bins within this range, how many can be specified by a parameter. Depending on how close a given value is to any given bin, the value of the bin will be affected. For example, if the value is right in the center of the bin, the value may be 1. If it close to the bin, it could be 0.7. If it is far, it will be 0. The drop-off follows a gaussian curve.

In the figure below, you can see how each of the 5 bins reacts to the different input values. You can see that the value that would otherwise correspond to a firing rate of 0.6, is around the same for the green bin, but the red bin will have a lower firing rate for this particular input sample.

In this example, we will create a bin encoder and encode two features. One is between -2 and 2, and the other between -5 and 5. We encode each one with 3 bins. This means we get 2(features) * 3(bins) = 6(spiketrains)

encoder = BinEncoder(

10,

min_values=np.array([-2, -5]),

max_values=np.array([2, 5]),

n_bins=3,

)

spike_train = encoder.encode(np.array([1.8, 0]))The first 3 spiketrains correspond to the first feature and the last 3 to the second one. It should look as follows

[[[0 0 1 0 1 0]]

[[0 0 1 0 1 0]]

[[0 0 1 0 1 0]]

[[0 0 1 0 1 0]]

[[0 0 1 0 1 0]]

[[0 0 1 0 1 0]]

[[0 0 1 0 1 0]]

[[0 0 1 0 1 0]]

[[0 0 1 0 1 0]]]

We are grateful for the support from our organizations and welcome contributions from the community! We hope this list of contributing organizations will grow much further as the project develops.

If you're interested in improving this project, please feel free to clone the repository, make your changes, and submit a pull request. Make sure to tell us your organisation if you want it added to the list. Check out our guidelines on testing and formatting in the sections below or browse the Issues tab. We look forward to your contributions!

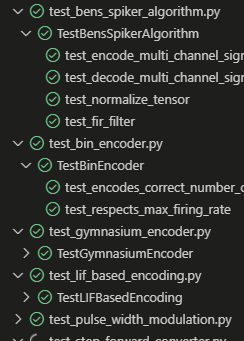

If you want to work on this repository, please note that we are using unittests to test our components. You can run our unittests in vs code by going to the testing tab and running the configuration. Select unittests as the testing framework and the root directory as the directory to run from. The result should look like this

An example of how the unittests might look in your VS code.In order to ensure consistent formatting, please install the "black formatter" extension. Follow the instructions on the extension page to ensure it is active. Furthermore, please enable "Format on Save" if you are using VS Code, or the equivalent if you are using a different IDE.

Make sure to run bash tag_release.sh <version> for every release in order to trigger updates on PiPy. This will activate the workflow in .github/workflows/workflow.yml which will build and release the new verison.

An example of this call could be bash tag_release.sh 0.1.3

Copyright © 2025 Alexandru Vasilache

This project is licensed under the MIT License. See the LICENSE file for details.

If you use this repository in your research, please cite the following paper:

@misc{vasilache2025pytorchcompatiblespikeencodingframework,

title={A PyTorch-Compatible Spike Encoding Framework for Energy-Efficient Neuromorphic Applications},

author={Alexandru Vasilache and Jona Scholz and Vincent Schilling and Sven Nitzsche and Florian Kaelber and Johannes Korsch and Juergen Becker},

year={2025},

eprint={2504.11026},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.LG},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.11026},

}Footnotes

-

B. Schrauwen and J. Van Campenhout, “Bsa, a fast and accurate spike train encoding scheme,” in Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, 2003., vol. 4. IEEE, 2003, pp. 2825–2830. ↩ ↩2

-

N. Kasabov, N. M. Scott, E. Tu, S. Marks, N. Sengupta, E. Capecci, M. Othman, M. G. Doborjeh, N. Murli, R. Hartono et al., “Evolving spatio-temporal data machines based on the neucube neuromorphic framework: Design methodology and selected applications,” Neural Networks, vol. 78, pp. 1–14, 2016 ↩ ↩2

-

S. Y. A. Yarga, J. Rouat, and S. Wood, “Efficient spike encoding algorithms for neuromorphic speech recognition,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Neuromorphic Systems 2022, 2022, pp. 1–8. ↩ ↩2

-

A. Arriandiaga, E. Portillo, J. I. Espinosa-Ramos, and N. K. Kasabov, “Pulsewidth modulation-based algorithm for spike phase encoding and decoding of time-dependent analog data,” IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, vol. 31, no. 10, pp. 3920–3931, 2019. ↩ ↩2

-

The gymnasium encoder is a custom encoder specifically tailored for gymnasium environments. ↩

-

The bin encoder is based on gaussian receptive fields and splits each input into multiple spike trains, as determined by the number of bins. ↩