A minimalist roadmap to the Data Science World, based on the Kaggle's courses, plus some COOL stuffs. For the Kaggle's courses, all credits goes to their instructors.

Python

Pandas

Geospatial Analysis

Intro to Machine Learning

Intermediate Machine Learning

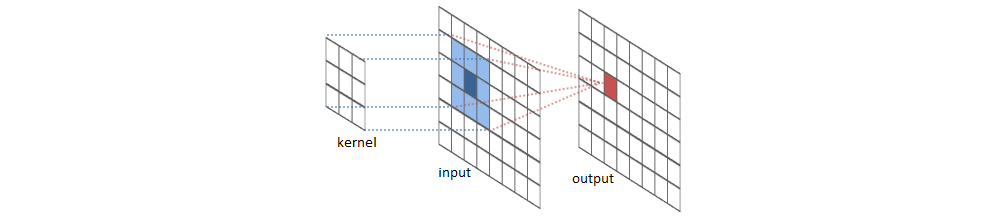

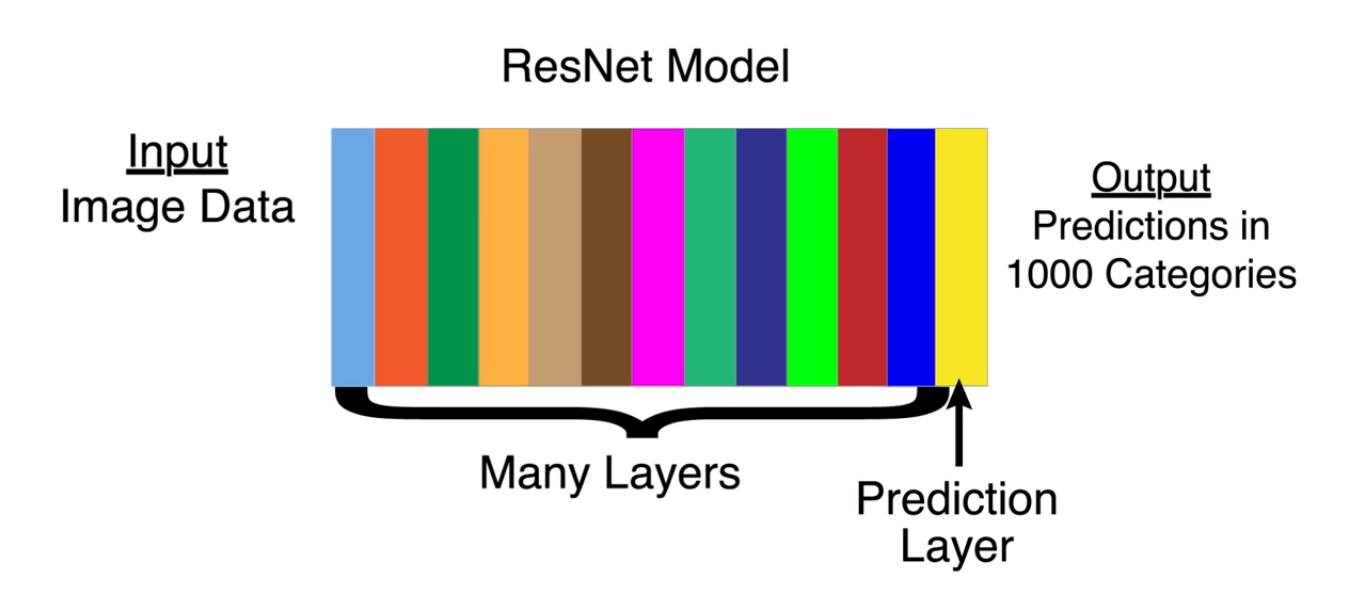

Deep Learning

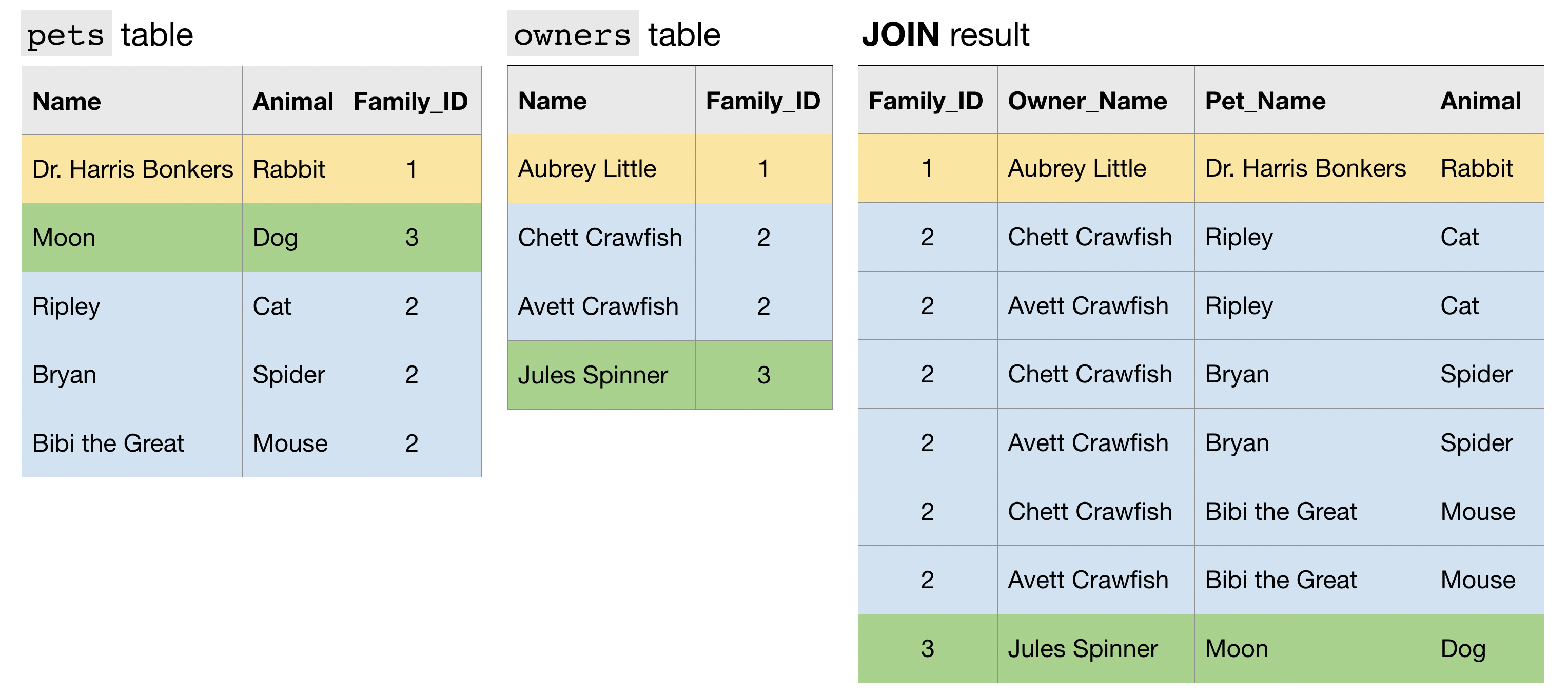

Intro to SQL

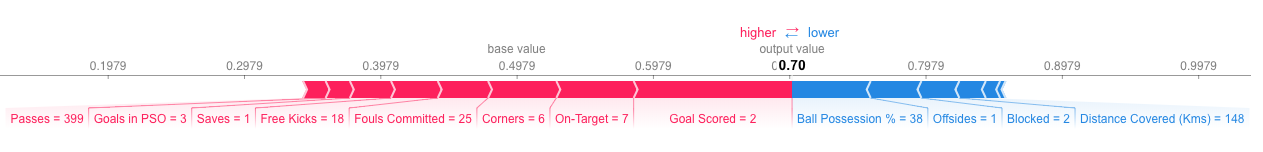

Machine Learning Explainability

Learn the most important language for data science.

A quick introduction to Python syntax, variable assignment, and numbers. #

=func(var)

var.func()/ # true division

// # floor division

% # modulus

** # exponentiationmin()

max()

abs()# conversion functions

int()

float()Calling functions and defining our own, and using Python's builtin documentation. #

on modules, objects, instances, and ...

help()

dir()def func_name(vars):

# some useful codes

return # some useful results""" some useful info about the function """ # `help()` returns thisprint()print(..., sep="\t")fn(fn(arg))

string.lower().split()Using booleans for branching logic. #

True

False

bool()a == b # a equal to b

a != b # a not equal to b

a < b # a less than b

a > b # a greater than b

a <= b # a less than or equal to b

a >= b # a greater than or equal to bPEMDAS combined with Boolean Values

()

**

+x, -x, ~x

*, /, //, %

+, -

<<, >>

&

^

|

==, !=, >, >=, <, <=, is, is not, in, not in

not

and

orif

elif

else- All numbers are treated as

True, except0. - All strings are treated as

True, except the empty string"". - Empty sequences (strings, lists, tuples, sets) are

Falseand the rest areTrue.

Setting a variable to either of two values depending on a condition.

outcome = "failed" if grade < 50 else "passed"Lists and the things you can do with them. Includes indexing, slicing and mutating. #

A mutable mix of same or different types of variables

[]

list()planets = ["Mercury", "Venus", "Earth", "Mars", "Jupiter"]

planets[0] # first element

planets[-1] # last elementplanets[:3]

planets[-3:]planets[:3] = ["Mur", "Vee", "Ur"]len()

sorted()

max()

sum()

any()Everything is an Object.

# complex number object

c = 12 + 5j

c.imag

c.real# integer number object

x = 12

x.bit_length()list.append()

list.pop()

list.index()

inImmutable.

()

,

tuple()x = 0.125

numerator, denominator = x.as_integer_ratio()For and while loops, and a much-loved Python feature: list comprehensions. #

Use in every iteratable objects: list, tuples, strings, ...

for - in - :

# some useful codesrange()while

[- for - in -]squares = [n ** 2 for n in range(10)]

# constant

[32 for planet in planets]# with if

short_planets = [planet.upper() + "!" for planet in planets if len(planet) < 6]# combined with other functions

return len([num for num in nums if num < 0])

return sum([num < 0 for num in nums])

return any([num % 7 == 0 for num in nums])Solving a problem with less code is always nice, but it's worth keeping in mind the following lines from The Zen of Python.

Readability counts.

Explicit is better than implicit.

for index, item in enumerate(items):

# some useful codesWorking with strings and dictionaries, two fundamental Python data types. #

Immutable.

""

""" """

str()[char + "! " for char in "Planet"]

>>> ['P! ', 'l! ', 'a! ', 'n! ', 'e! ', 't! ']"Planet"[0] = "M"

>>> TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignmentstr.upper()

str.lower()

str.index()

str.startswith()

str.endswith()# split

year, month, day = '2020-03-05'.split('-')

year, month, day

>>> ('2020', '03', '05')# join

'/'.join([month, day, year])

>>> '03/05/2020'"{}".format()

f"{}"Pairs of keys,values.

{}

dict()numbers = {"one": 1, "two": 2, "three": 3}

numbers["one"]

numbers["eleven"] = 11planet_to_initial = {planet: planet[0] for planet in planets}dict.keys()

dict.values()" ".join(sorted(planet_to_initial.values()))key_of_min_value = min(numbers, key=numbers.get)"M" in planet_to_initial.values()

>>> True# loop over keys

for planet in planet_to_initial:

print(planet)# loop over (key, value) pairs using `item`

for planet, initial in planet_to_initial.items():

print(f'{planet} begins with "{initial}"')Imports, operator overloading, and survival tips for venturing into the world of external libraries. #

# simple import, `.` access

import math

math.pi# `as` import, short `.` access

import math as mt

mt.pi# `*` import, simple access

from math import *

piThe problem of * import is that some modules (ex. math and numpy) have functions with same name (ex. log) but with different semantics. So one of them overwrites (or "shadows") the other. It is called overloading.

# combined, solution for the `*` import

from math import log, pi

from numpy import asarrayModules contain variables which can refer to functions or values. Sometimes they can also have variables referring to other modules.

import numpy

dir(numpy.random)

>>> ['set_state', 'shuffle', 'standard_cauchy', 'standard_exponential', 'standard_gamma', 'standard_normal', 'standard_t', 'test', 'triangular', 'uniform', ...]# make an array of random numbers

rolls = numpy.random.randint(low=1, high=6, size=10)

rolls

>>> array([3, 2, 5, 2, 4, 2, 2, 3, 2, 3])Standard Python datatypes are: int, float, bool, list, str, and dict.

As you work with various libraries for specialized tasks, you'll find that they define their own types. For example

- Matplotlib:

Subplot,Figure,TickMark, andAnnotation - Pandas:

DataFrameandSeries - Tensorflow:

Tensor

Use type() to find the type of an object. Use dir() and help() for more details.

dir(numpy.ndarray)

>>> [...,'__bool__', ..., '__delattr__', '__delitem__', '__dir__', ..., '__sizeof__', ..., 'max', 'mean', 'min', ..., 'sort', ..., 'sum', ..., 'tobytes', 'tofile', 'tolist', 'tostring', ...]# list

xlist = [[1, 2, 3], [2, 4, 6]]

xlist[1, -1]

>>> TypeError: list indices must be integers or slices, not tuple# numpy array

xarray = numpy.asarray(xlist)

xarray[1, -1]

>>> 6# list

[3, 4, 1, 2, 2, 1] + 10

>>> TypeError: can only concatenate list (not "int") to list# numpy array

rolls + 10

>>> array([13, 12, 15, 12, 14, 12, 12, 13, 12, 13])# tensorflow

import tensorflow as tf

a = tf.constant(1)

b = tf.constant(1)

a + b

>>> <tf.Tensor 'add:0' shape=() dtype=int32>When Python programmers want to define how operators behave on their types, they do so by implementing Dunder (Special) Methods, methods with special names beginning and ending with 2 underscores such as __add__ or __contains__. More info: https://is.gd/3zuhhL

The fundamental package for scientific computing with Python. #

NumPy’s main object is the homogeneous n-dimensional array. It is a table of elements (usually numbers), all of the same type, indexed by a tuple of non-negative integers. In NumPy dimensions are called axes. NumPy’s array class is called ndarray. Note that numpy.array is not the same as the Standard Python Library class array.array, which only handles one-dimensional arrays and offers less functionality.

# create an array with a single sequence as an argument

import numpy as np

a = np.array([2, 3, 4])

a.ndim # number of axes

>>> 1

a.shape # size of array in each dimension

>>> (1, 3)

a.size # total number of elements

>>> 3

a.dtype.name # type of elements

>>> 'int64'# sequences as arguments + dtype

c = np.array([[1, 2], [3, 4]], dtype=complex)

c

>>> array([[1.+0.j, 2.+0.j],

[3.+0.j, 4.+0.j]])NumPy offers several functions to create arrays with initial placeholder content. The function zeros creates an array full of zeros, the function ones creates an array full of ones, and the function empty creates an array whose initial content is random and depends on the state of the memory. By default, the dtype of the created array is float64.

np.ones((2, 3, 4), dtype=np.int16)

>>> array([[[1, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1]],

[[1, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1]]], dtype=int16)To create sequences of numbers, NumPy provides the arange function which is analogous to the Python built-in range, but returns an array.

a = np.arange(15).reshape(3, 5)

a

>>> array([[ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4],

[ 5, 6, 7, 8, 9],

[10, 11, 12, 13, 14]])np.arange(0, 2, 0.3)

>>> array([0. , 0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, 1.5, 1.8])Function linspace receives as an argument the number of elements that we want, instead of the step. It's useful to evaluate function at lots of points

from numpy import pi

x = np.linspace(0, 2 * pi, 100)

f = np.sin(x)On NumPy arrays, arithmetic operators apply elementwise, even the product operator *, unlike in many matrix languages. The matrix product can be performed using the @ operator or the dot function. NumPy provides familiar mathematical functions such as sin, cos, and exp. Some operations, such as += and *=, act in place to modify an existing array rather than create a new one.

a = np.array([20, 30, 40, 50])

b = np.arange(4)

a - b

b ** 2

10 * np.sin(a)

a < 35A = np.array([[1, 1], [0, 1]])

B = np.array([[2, 0], [3, 4]])

A * B # elementwise product

A @ B # matrix product

A.dot(B) # another matrix productMany unary operations are implemented as methods of the ndarray class. By default, these operations apply to the array as though it were a list of numbers, regardless of its shape. However, by specifying the axis parameter we can apply an operation along the specified axis of an array.

# create an instance of a random generator

rg = np.random.default_rng(1)

a = rg.random((2, 3))

a.sum() # sum of array

a.min(axis=0) # min of each column

a.cumsum(axis=1) # cumulative sum along each rowHere is a list of some useful NumPy functions ordered in categories. See Routines for the full list.

-

Array Creation:

arange,array,copy,empty,empty_like,eye,fromfile,fromfunction,identity,linspace,logspace,mgrid,ogrid,ones,ones_like,r_,zeros,zeros_like -

Conversions:

astype,atleast_1d,atleast_2d,atleast_3d,mat -

Manipulations:

apply_along_axis,array_split,column_stack,concatenate,diagonal,dsplit,dstack,hsplit,hstack,item,newaxis,ravel,repeat,reshape,resize,squeeze,swapaxes,take,transpose,vsplit,vstack -

Questions:

all,any,nonzero,where -

Ordering:

argmax,argmin,argsort,max,min,ptp,searchsorted,sort -

Operations:

average,ceil,choose,compress,cumprod,conj,cumsum,diff,floor,inner,invert,fill,imag,prod,put,putmask,real,round,sum -

Basic Statistics:

cov,corrcoef,mean,median,std,var -

Basic Linear Algebra:

cross,dot,outer,linalg.svd,vdot

When operating with arrays of different types, the type of the resulting array corresponds to the more general or precise one (a behavior known as upcasting).

(np.ones(3, dtype='int8') + np.linspace(0, pi, 3)).dtype.name

>>> 'float64'One-dimensional arrays can be indexed, sliced and iterated over, much like lists and other Python sequences.

a = np.arange(10) ** 3 # the first 10 cube numbers

a[2:5]

a[:6:2] = 1000 # from start-to-6, set every 2nd element to 1000

a[::-1] # reversed aMultidimensional arrays can have one index per axis. These indices are given in a tuple.

def f(x, y):

return 10 * x + y

b = np.fromfunction(f, (5, 4), dtype=int)

b[2, 3]

b[:, 1] # each row in the second column of b

b[1:3, :] # each column in the second and third row of b

b[-1] # the last row. equivalent to b[-1,:]The expression within brackets in b[i] is treated as an i followed by as many instances of : as needed to represent the remaining axes. NumPy also allows you to write this using dots as b[i, ...]. The dots (...) represent as many colons as needed to produce a complete indexing tuple. For example, if x is an array with 5 axes, then x[1, 2, ...] is equivalent to x[1, 2, :, :, :].

Iterating over multidimensional arrays is done with respect to the first axis. However, if we want to perform an operation on each element in the array, we can use the flat attribute which is an iterator over all the elements of the array.

for element in b.flat:

print(element)NumPy offers more indexing facilities than regular Python sequences. In addition to indexing by integers and slices, as we saw before, arrays can be indexed by arrays of integers and arrays of booleans.

a = np.arange(12) ** 2 # the first 12 square numbers

i = np.array([1, 1, 3, 8, 5]) # an array of indices

a[i] # the elements of a at the positions i

>>> array([ 1, 1, 9, 64, 25])

j = np.array([[3, 4], [9, 7]]) # a bidimensional array of indices

a[j] # the same shape as j

>>> array([[ 9, 16],

[81, 49]])a = np.arange(12).reshape(3, 4)

a

>>> array([[ 0, 1, 2, 3],

[ 4, 5, 6, 7],

[ 8, 9, 10, 11]])

i = np.array([[0, 1], [1, 2]])

j = np.array([[2, 1], [3, 3]])

a[i, j]

>>> array([[ 2, 5],

[ 7, 11]])

a[i, 2] # broadcasting

>>> array([[ 2, 6],

[ 6, 10]])We can also use indexing with arrays as a target to assign to.

a = np.arange(5)

a[[1, 3, 4]] = 0

a

>>> array([0, 0, 2, 0, 0])However, when the list of indices contains repetitions, the assignment is done several times, leaving behind the last value.

a = np.arange(5)

a[[0, 0, 2]] = [1, 2, 3]

a

>>> array([2, 1, 3, 3, 4])a = np.arange(5)

a[[0, 0, 2]] += 1

a

>>> array([1, 1, 3, 3, 4]) # the 0th element is only incremented onceWhen we index arrays with arrays of (integer) indices we are providing the list of indices to pick. With boolean indices the approach is different; we explicitly choose which items in the array we want and which ones we don’t. This can be very useful in assignments.

a = np.arange(12).reshape(3, 4)

b = a > 4

b # b is a boolean with a's shape

>>> array([[False, False, False, False],

[False, True, True, True],

[ True, True, True, True]])

a[b] # 1d array with the selected elements

>>> array([ 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11])

a[b] = 0 # All elements of 'a' higher than 4 become 0

a

>>> array([[0, 1, 2, 3],

[4, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0]])The second way of indexing with booleans is that for each dimension of the array we give a 1D boolean array selecting the slices we want.

a = np.arange(12).reshape(3, 4)

b1 = np.array([False, True, True]) # first dim selection

b2 = np.array([True, False, True, False]) # second dim selection

a[b1, :] # selecting rows

>>> array([[ 4, 5, 6, 7],

[ 8, 9, 10, 11]])

a[:, b2] # selecting columns

>>> array([[ 0, 2],

[ 4, 6],

[ 8, 10]])

a[b1][:, b2]

>>> array([[ 4, 6],

[ 8, 10]])

a[b1, b2] # a weird thing to do

>>> array([ 4, 10])The ix_ function can be used to construct an open mesh from multiple sequences. This function takes N 1-D sequences and returns N outputs with N dimensions each. Using ix_ one can quickly construct index arrays that will index the cross product.

a = np.arange(10).reshape(2, 5)

a

>>> array([[0, 1, 2, 3, 4],

[5, 6, 7, 8, 9]])

ixgrid = np.ix_([0, 1], [2, 4])

ixgrid

>>> (array([[0],

[1]]), array([[2, 4]]))

ixgrid[0].shape, ixgrid[1].shape

>>> ((2, 1), (1, 2))

a[ixgrid]

>>> array([[2, 4],

[7, 9]])

ixgrid = np.ix_([True, True], [2, 4])

a[ixgrid]

>>> array([[2, 4],

[7, 9]])An array has a shape given by the number of elements along each axis. The shape of an array can be changed with various commands. Note that the following three commands all return a modified array, but do not change the original array.

a.ravel() # returns the array, flattened

a.transpose() # returns the array, transposed

a.reshape() # returns the array with a modified shapeThe reshape function returns its argument with a modified shape, whereas the resize function modifies the array itself. And, if a dimension is given as -1 in a reshaping operation, the other dimensions are automatically calculated.

Several arrays can be stacked together along different axes, vertically with vstack and horizontally with hstack. The function column_stack stacks 1D arrays as columns into a 2D array. It is equivalent to hstack only for 2D arrays. On the other hand, the function row_stack is equivalent to vstack for any input arrays. In general, for arrays with more than two dimensions, hstack stacks along their second axes, vstack stacks along their first axes, and concatenate allows for an optional arguments giving the number of the axis along which the concatenation should happen.

np.column_stack is np.hstack

>>> False

np.row_stack is np.vstack

>>> TrueUsing hsplit, we can split an array along its horizontal axis, either by specifying the number of equally shaped arrays to return, or by specifying the columns after which the division should occur. vsplit splits along the vertical axis, and array_split allows one to specify along which axis to split.

a = np.floor(10 * rg.random((2, 12)))

a

>>> array([[6., 7., 6., 9., 0., 5., 4., 0., 6., 8., 5., 2.],

[8., 5., 5., 7., 1., 8., 6., 7., 1., 8., 1., 0.]])

# split a into 3

np.hsplit(a, 3)

>>> [array([[6., 7., 6., 9.], [8., 5., 5., 7.]]),

array([[0., 5., 4., 0.], [1., 8., 6., 7.]]),

array([[6., 8., 5., 2.], [1., 8., 1., 0.]])]

# split a after the 3rd and the 4th column

np.hsplit(a, (3, 4))

>>> [array([[6., 7., 6.], [8., 5., 5.]]),

array([[9.], [7.]]),

array([[0., 5., 4., 0., 6., 8., 5., 2.], [1., 8., 6., 7., 1., 8., 1., 0.]])]When operating and manipulating arrays, their data is sometimes copied into a new array and sometimes not. There are three cases:

- No Copy at All - Simple assignments (

b = a) make no copy of objects or their data. - Shallow Copy or View - The

viewmethod creates a new array object that looks at the same data. Slicing an array returns a view of it too. Changing the data in a view, changes the base data. - Deep Copy - The

copymethod makes a complete copy of the array and its data. Sometimescopyshould be called after slicing if the original array, maybe a huge intermediate result, is not required anymore.

a = np.array([[ 0, 1, 2, 3],

[ 4, 5, 6, 7],

[ 8, 9, 10, 11]])

b = a # no new object is created

b is a

>>> True

c = a[:, 1:3]

c.base is a

>>> True

c[:] = 10 # c[:] is a view of c, a's data changes

d = a.copy()

d.base is a # d doesn't share anything with a

>>> FalseSolve short hands-on challenges to perfect your data manipulation skills.

You can't work with data if you can't read it. #

It is a table and contains an array of individual entries. Each entry corresponds to a row (or record) and a column.

import pandas as pd

pd.DataFrame({"Apples": [50, 21], "Bananas": [131, 2]})The syntax for declaring a new one is a dictionary whose keys are the column names, and whose values are a list of entries.

The list of row labels used in a DataFrame is known as an Index. We can assign values to it by using an index parameter in our constructor.

pd.DataFrame(

{"Apples": [50, 21], "Bananas": [131, 2]}, index=["2018 Sales", "2019 Sales"]

)In essence, it is a single column of a DataFrame, a sequence of data values.

pd.Series([30, 50, 21])You can assign column values to the Series the same way as before, using an index parameter. However, a Series does not have a column name, it only has one overall name.

pd.Series([30, 50, 21], index=["2017 Sales", "2018 Sales", "2019 Sales"], name="Apples")Data can be stored in any of a number of different forms and formats. By far the most basic of these is the humble CSV file. A CSV file is a table of values separated by commas.

# load data

wine_reviews = pd.read_csv(

"../input/wine-reviews/winemag-data-130k-v2.csv", index_col=0

)- If your CSV file has a built-in index, pandas can use that column for the index (instead of creating a new one automatically).

# data dimention

wine_reviews.shape

# columns' name

wine_reviews.columns

# top rows

wine_reviews.head()

# bottom rows

wine_reviews.tail()animals = pd.DataFrame(

{"Cows": [12, 20], "Goats": [22, 19]}, index=["Year 1", "Year 2"]

)

animals.to_csv("cows_and_goats.csv")Pro data scientists do this dozens of times a day. You can, too! #

In Python, we can access the property of an object by accessing it as an attribute. A reviews object, might have a country property, which we can access by calling reviews.country. Columns in a pandas DataFrame work in much the same way.

If we have a Python dictionary, we can access its values using the indexing [] operator.

# select the `country` column

reviews["country"]A pandas Series looks kind of like a dictionary. So, to drill down to a single specific value, we need only use the indexing operator [] once more.

# select the first value from the `country` column

reviews["country"][0]

>>> 'Italy'For more advanced operations, pandas has its own accessor operators, iloc and loc.

Selecting data based on its numerical position in the data, like a matrix.

# select the first row

reviews.iloc[0]

# select the first column, `:` means everything

reviews.iloc[:, 0]

# select the first value from the `country` column

reviews["country"].iloc[0]

# select the last five elements of the dataset

reviews.iloc[-5:]Selecting data based on its index value, with inclusive range.

# select the first value from the `country` column

reviews.loc[0, "country"]

# select all the entries from three specific columns

reviews.loc[:, ["taster_name", "taster_twitter_handle", "points"]]# select first three rows

reviews.iloc[:3]

# or

reviews.loc[:2]# select the first 100 records of the `country` and `variety` columns.

cols_idx = [0, 11]

reviews.iloc[:100, cols_idx]

# or

cols = ["country", "variety"]

reviews.loc[:99, cols]reviews.set_index("title")To do interesting things with the data, we often need to ask questions based on conditions.

To combine multiple conditions in pandas, bitwise operators must be used.

& # AND x & y

| # OR x | y

^ # XOR x ^ y

~ # NOT ~x

>> # right shift x>>

<< # left shift x<<For example, suppose that we're interested in better-than-average wines produced in Italy.

cond1 = reviews["country"] == "Italy"

cond2 = reviews["points"] >= 90

reviews.loc[cond1 & cond2]isin() lets you select data whose value "is in" a list of values.

# select wines only from Italy or France

reviews.loc[reviews["country"].isin(["Italy", "France"])]isna() and notna() let you highlight values which are (or are not) empty (NaN).

# filter out wines lacking a price tag in the dataset

reviews.loc[reviews["price"].notna()]isnull()is an alias forisna(), same asnotnull()fornotna().

# query a df like SQL datasets

wine_reviews.query("price > 100 and country = 'Italy'")# you can assign either a constant value

reviews["critic"] = "everyone"

# or with an iterable of values

reviews["index_backwards"] = range(len(reviews), 0, -1)Extract insights from your data. #

# get summary statistic about a DataFrame

reviews.describe()count: shows how many rows have non-missing values.mean: the average.std: the standard deviation, measures how numerically spread out the values are.min,25%(25th percentile),50%(50th percentiles),75%(75th percentiles) andmax

# get summary statistic about a Series

reviews["points"].describe()

# see the mean

reviews["points"].mean()

# see a list of unique values

reviews["points"].unique()

# see a list of unique values and how often they occur

reviews["points"].value_counts()

# get the titles & points of the 3 highest point

reviews["points"].nlargest(3)# get the title of the wine with the highest points-to-price ratio

max_p2pr = (reviews["points"] / reviews["price"]).idxmax()

reviews.loc[max_p2pr, "title"]

>>> 'Bandit NV Merlot (California)'A function that takes one set of values and "maps" them to another set of values, for creating new representations from existing data.

# remean the scores the wines received to 0

review_points_mean = reviews["points"].mean()

reviews["points"].map(lambda p: p - review_points_mean)# create a series counting how many times each of "tropical" or "fruity" appears in the description column

n_tropical = reviews["description"].map(lambda desc: "tropical" in desc).sum()

n_fruity = reviews["description"].map(lambda desc: "fruity" in desc).sum()

pd.Series([n_tropical, n_fruity], index=["tropical", "fruity"])The function you pass to map() should expect a single value from the Series (a point value, in the above example), and return a transformed version of that value. map() returns a new Series.

# remean the scores the wines received to 0

def remean_points(row):

row["points"] = row["points"] - review_points_mean

return row

reviews.apply(remean_points, axis="columns")# create a series with the number of stars corresponding to each review

def stars(row):

# any wines from country X should automatically get 3 stars, because of ADs' MONEY!

if row["country"] == "X":

return 3

elif row["points"] >= 95:

return 3

elif row["points"] >= 85:

return 2

else:

return 1

reviews.apply(stars, axis="columns")apply() is the equivalent method if we want to transform a whole DataFrame by calling a custom method on each row. apply() returns a new DataFrame.

If we had called reviews.apply() with axis="index", then instead of passing a function to transform each row, we would need to give a function to transform each column.

They perform a simple operation between a lot of values on the left and a single (a lot of) value(s) on the right.

# remean the scores the wines received to 0

review_points_mean = reviews["points"].mean()

reviews["points"] - review_points_mean# combine country and region information in the dataset

reviews["country"] + " - " + reviews["region_1"]These operators are faster than map() or apply() because they uses speed ups built into pandas. All of the standard Python operators (>, <, ==, and so on) work in this manner.

However, they are not as flexible as map() or apply(), which can do more advanced things, like applying conditional logic, which cannot be done with addition and subtraction alone.

Scale up your level of insight. The more complex the dataset, the more this matters. #

Maps allow us to transform data in a DataFrame or Series one value at a time for an entire column. However, often we want to group our data, and then do something specific to the group the data is in.

# replicate what `value_counts()` does

reviews.groupby("points")["points"].count()

# get the minimum price from each group of points

reviews.groupby("points")["price"].min()

# get a series whose index is the taster_twitter_handle values count how many reviews each person wrote

reviews.groupby("taster_twitter_handle").size()

# or

reviews.groupby("taster_twitter_handle")["taster_twitter_handle"].count()

# get the title of the first wine reviewed from each winery

reviews.groupby("winery").apply(lambda df: df["title"].iloc[0])# get a dataframe whose index is the variety category and values are the `min` and `max` prices

reviews.groupby("variety")["price"].agg([min, max])# pick out the best wine by country and province

reviews.groupby(["country", "province"]).apply(lambda df: df.loc[df["points"].idxmax()])Multi-indices have several methods for dealing with their tiered structure which are absent for single-level indices.

They also require two levels of labels to retrieve a value.

The use cases for a multi-index are detailed alongside instructions on using them in the MultiIndex / Advanced Selection section of the pandas documentation.

# convert back to a regular index

count_prov_best.reset_index()# sort (country, province) based on how many reviews are belong to

count_prov_reviewed = reviews.groupby(["country", "province"])["description"].agg([len])

count_prov_reviewed.reset_index().sort_values(by="len", ascending=False)count_prov_reviewed.reset_index().sort_values(by=["country", "len"], ascending=False)# get a series whose index is wine prices and values is the maximum points a wine costing that much was given in a review. sort the values by price, ascending

reviews.groupby("price")["points"].max().sort_index(ascending=True)Deal with the most common progress-blocking problems. #

The data type for a column in a DataFrame or a Series is known as the dtype.

int64,float64,object

# a dataframe

reviews.dtypes

# a series

reviews["price"].dtype

# a dataframe or series index

reviews.index.dtype

# convert a dtype

reviews["points"].astype("float64")# get a series of True & False, based on where NaNs are

reviews["price"].isna()

# find the number of NaNs

reviews["price"].isna().sum()

# create a dataframe of rows with missing country

reviews[reviews["country"].isna()]isnull()is an alias forisna(), same asnotnull()fornotna().

# fill NaNs with Unknown

reviews["region_1"].fillna("Unknown")# replace missing data which is given some kind of sentinel values

reviews["region_1"].replace(["Unknown", "Undisclosed", "Invalid"], "NaN")# filter rows with NaNs

reviews.dropna(axis=0)

# filter columns with NaNs

reviews.dropna(axis=1)Data comes in from many sources. Help it all make sense together. #

# change the names of columns

reviews.rename(columns={"region_1": "region", "region_2": "locale"})

# change the indices of rows

reviews.rename(index={0: "firstEntry", 1: "secondEntry"})# change the names of axes, form rows to wines, from columns to fields

reviews.rename_axis("wines", axis="rows").rename_axis("fields", axis="columns")We will sometimes need to combine different DataFrames and/or Series. Pandas has three core methods for doing this. In order of increasing complexity, these are

It will smush a list of elements together along an axis.

This is useful when we have data in different DataFrame or Series objects but having the same columns.

canadian_yt = pd.read_csv("../input/youtube-new/CAvideos.csv")

british_yt = pd.read_csv("../input/youtube-new/GBvideos.csv")

pd.concat([canadian_yt, british_yt])It lets you combine different DataFrame objects which have an index in common.

# pull down videos that happened to be trending on the same day in both Canada and the UK

left = canadian_yt.set_index(["title", "trending_date"])

right = british_yt.set_index(["title", "trending_date"])

left.join(right, lsuffix="_CAN", rsuffix="_UK")- The

lsuffixandrsuffixparameters are necessary when the data has the same column names in both datasets.

Make great data visualizations. A great way to see the power of coding!

Visualize trends over time. #

import pandas as pd

pd.plotting.register_matplotlib_converters()

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

import seaborn as sns# load a timeseries data file

spotify_data = pd.read_csv("../input/spotify.csv", index_col="Date", parse_dates=True)

# set the width and height of the figure

plt.figure(figsize=(14, 6))

# add title

plt.title("Daily Global Streams of Popular Songs in 2017-2018")

# plot a line chart for daily global streams of each song

sns.lineplot(data=spotify_data)

# plot a subset of the data

sns.lineplot(data=spotify_data["Shape of You"], label="Shape of You")

# add label for horizontal axis

plt.xlabel("Date")Use color or length to compare categories in a dataset. #

# load data

flight_data = pd.read_csv("../input/flight_delays.csv", index_col="Month")

# add title

plt.title("Average Arrival Delay for Spirit Airlines Flights, by Month")

# rotate labels for horizontal axis

plt.xticks(rotation="vertical")

# plot a bar chart, showing average arrival delay for Spirit Airlines flights by month

sns.barplot(x=flight_data.index, y=flight_data["NK"])

# add label for vertical axis

plt.ylabel("Arrival delay (in minutes)")- Note: You must select the indexing column with

flight_data.index, and it is not possible to useflight_data['Month'], because when we loaded the dataset, the"Month"column was used to index the rows.

# add title

plt.title("Average Arrival Delay for Each Airline, by Month")

# plot a heatmap, showing average arrival delay for each airline by month

sns.heatmap(data=flight_data, annot=True)

# add label for horizontal axis

plt.xlabel("Airline")# get the maximum average delay on March

flight_data.loc[3].max()

# find the aireline with the minimum average delay on October

flight_data.loc[10].idxmin()Leverage the coordinate plane to explore relationships between variables. #

# load data

insurance_data = pd.read_csv("../input/insurance.csv")

# a simple scatter plot

sns.scatterplot(x=insurance_data["bmi"], y=insurance_data["charges"])

# add a regression line

sns.regplot(x=insurance_data["bmi"], y=insurance_data["charges"])

# a color-coded scatter plot

sns.scatterplot(

x=insurance_data["bmi"], y=insurance_data["charges"], hue=insurance_data["smoker"]

)

# add two regression lines, corresponding to hue

sns.lmplot(x="bmi", y="charges", hue="smoker", data=insurance_data)

# a categorical scatter plot with non-overlapping points (swarmplot)

sns.swarmplot(x=insurance_data["smoker"], y=insurance_data["charges"])Create histograms and density plots. #

# load data

iris_data = pd.read_csv("../input/iris.csv", index_col="Id")

# a simple histogram

sns.distplot(a=iris_data["Petal Length (cm)"], kde=False)

# a kde (kernel density estimate) plot

sns.kdeplot(data=iris_data["Petal Length (cm)"], shade=True)

# a 2D kde plot

sns.jointplot(

x=iris_data["Petal Length (cm)"], y=iris_data["Sepal Width (cm)"], kind="kde"

)# load data

iris_set_data = pd.read_csv("../input/iris_setosa.csv", index_col="Id")

iris_ver_data = pd.read_csv("../input/iris_versicolor.csv", index_col="Id")

iris_vir_data = pd.read_csv("../input/iris_virginica.csv", index_col="Id")

# kde plots for each one, histograms can be used too

sns.kdeplot(data=iris_set_data["Petal Length (cm)"], label="Setosa", shade=True)

sns.kdeplot(data=iris_ver_data["Petal Length (cm)"], label="Versicolor", shade=True)

sns.kdeplot(data=iris_vir_data["Petal Length (cm)"], label="Virginica", shade=True)

# force legend to appear

plt.legend()Decide how to best tell the story behind your data. #

- A trend is defined as a pattern of change.

sns.lineplot- Line charts are best to show trends over a period of time, and multiple lines can be used to show trends in more than one group.

sns.barplot- Bar charts are useful for comparing quantities corresponding to different groups.sns.heatmap- Heatmaps can be used to find color-coded patterns in tables of numbers.sns.scatterplot- Scatter plots show the relationship between two continuous variables; if color-coded, we can also show the relationship with a third categorical variable.sns.regplot- Including a regression line in the scatter plot makes it easier to see any linear relationship between two variables.sns.lmplot- This command is useful for drawing multiple regression lines, if the scatter plot contains multiple, color-coded groups.sns.swarmplot- Categorical scatter plots show the relationship between a continuous variable and a categorical variable.

- A distribution shows the possible values that we can expect to see in a variable, along with how likely they are.

sns.distplot- Histograms show the distribution of a single numerical variable.sns.kdeplot- KDE plots (or 2D KDE plots) show an estimated, smooth distribution of a single numerical variable (or two numerical variables).sns.jointplot- This command is useful for simultaneously displaying a 2D KDE plot with the corresponding KDE plots for each individual variable.

Practice for real-world application. #

# list all your datasets' folders

import os

print(os.listdir("../input"))How to put your new skills to use for your next personal or work project. #

Create interactive maps, and discover patterns in geospatial data.

Get started with plotting in GeoPandas. #

With this course you can find solutions for several real-world problems like:

- Where should a global non-profit expand its reach in remote areas of the Philippines?

- How do purple martins, a threatened bird species, travel between North and South America? Are the birds travelling to conservation areas?

- Which areas of Japan could potentially benefit from extra earthquake reinforcement?

- Which Starbucks stores in California are strong candidates for the next Starbucks Reserve Roastery location?

- ...

import geopandas as gpdThe data was loaded into a (GeoPandas) GeoDataFrame object has all of the capabilities of a (Pandas) DataFrame. So, every command that you can use with a DataFrame will work with the data!

There are many, many different geospatial file formats, such as shapefile, GeoJSON, KML, and GPKG.

- shapefile is the most common file type that you'll encounter, and

- all of these file types can be quickly loaded with the

read_file()function.

Every GeoDataFrame contains a special geometry column. It contains all of the geometric objects that are displayed when we call the plot() method. While this column can contain a variety of different datatypes, each entry will typically be a Point, LineString, or Polygon.

Create it layer by layer.

# load data

world_loans = gpd.read_file(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/kiva_loans/kiva_loans/kiva_loans.shp"

)

# define a base map with county boundaries

world = gpd.read_file(gpd.datasets.get_path("naturalearth_lowres"))

ax = world.plot(

figsize=(20, 20), color="whitesmoke", linestyle=":", edgecolor="lightgray"

)

# add loans to the base map

world_loans.plot(ax=ax, color="black", markersize=2)You can subset the data for more details.

# subset the data

phl_loans = world_loans.loc[world_loans["country"] == "Philippines"].copy()

# enable fiona driver & load a KML file containing island boundaries

gpd.io.file.fiona.drvsupport.supported_drivers["KML"] = "rw"

phl = gpd.read_file(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/Philippines_AL258.kml", driver="KML"

)

# define a base map with county boundaries

ax_ph = phl.plot(

figsize=(20, 20), color="whitesmoke", linestyle=":", edgecolor="lightgray"

)

# add loans to the base map

phl_loans.plot(ax=ax_ph, color="black", markersize=2)It's pretty amazing that we can represent the Earth's surface in 2 dimensions! #

The world is a three-dimensional globe. So we have to use a map projection method to render it as a flat surface. Map projections can't be 100% accurate. Each projection distorts the surface of the Earth in some way, while retaining some useful property.

- The equal-area projections preserve area.

- The equidistant projections preserve distance.

We use a coordinate reference system (CRS) to show how the projected points correspond to real locations on Earth. CRSs are referenced by European Petroleum Survey Group (EPSG) codes.

When we create a GeoDataFrame from a shapefile, the CRS is already imported for us. But when creating a GeoDataFrame from a CSV file, we have to set the CRS to EPSG 4326, corresponds to coordinates in latitude and longitude.

# create a DataFrame with health facilities in Ghana

import pandas as pd

facilities_df = pd.read_csv(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/ghana/ghana/health_facilities.csv"

)

# convert the DataFrame to a GeoDataFrame

import geopandas as gpd

facilities = gpd.GeoDataFrame(

facilities_df,

geometry=gpd.points_from_xy(facilities_df.Longitude, facilities_df.Latitude),

)

# set the CRS code

facilities.crs = {"init": "epsg:4326"}- We begin by creating a DataFrame containing columns with latitude and longitude coordinates.

- To convert it to a GeoDataFrame, we use

gpd.GeoDataFrame(). - The

gpd.points_from_xy()function creates Point objects from the latitude and longitude columns.

Re-projecting refers to the process of changing the CRS. This is done in GeoPandas with the to_crs() method. For example, when plotting multiple GeoDataFrames, it's important that they all use the same CRS.

# load a GeoDataFrame containing regions in Ghana

regions = gpd.read_file(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/ghana/ghana/Regions/Map_of_Regions_in_Ghana.shp"

)

regions.crs

>>> 32630# create a map

ax = regions.plot(figsize=(8, 8), color="whitesmoke", linestyle=":", edgecolor="black")

facilities.to_crs(epsg=32630).plot(ax=ax, alpha=0.6, markersize=1, zorder=1)In case the EPSG code is not available in GeoPandas, we can change the CRS with what's known as the "proj4 string" of the CRS. The proj4 string to convert to latitude/longitude coordinates is:

# change the CRS to EPSG 4326

regions.to_crs("+proj=longlat +ellps=WGS84 +datum=WGS84 +no_defs")For an arbitrary GeoDataFrame, the type in the geometry column depends on what we are trying to show: for instance, we might use:

- a

Pointfor the epicenter of an earthquake, - a

LineStringfor a street, or - a

Polygonto show country boundaries.

All three types of geometric objects have built-in attributes that you can use to quickly analyze the dataset.

# get the x- or y-coordinates of a point from the x and y attributes

facilities["geometry"].x

# calculate the area (in square kilometers) of all polygons

sum(regions["geometry"].to_crs(epsg=3035).area) / 10 ** 6- ESPG 3035 Scope: Statistical mapping at all scales and other purposes where true area representation is required.

# load data

import pandas as pd

birds_df = pd.read_csv(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/purple_martin.csv", parse_dates=["timestamp"]

)

# create the GeoDataFrame

import geopandas as gpd

birds = gpd.GeoDataFrame(

birds_df,

geometry=gpd.points_from_xy(birds_df["location-long"], birds_df["location-lat"]),

)

# create GeoDataFrame showing path for each bird

from shapely.geometry import LineString

path_df = (

birds.groupby("tag-local-identifier")["geometry"]

.apply(list)

.apply(lambda x: LineString(x))

.reset_index()

)

path_gdf = gpd.GeoDataFrame(path_df, geometry=path_df["geometry"])

path_gdf.crs = {"init": "epsg:4326"}Learn how to make interactive heatmaps, choropleth maps, and more! #

# load data

import pandas as pd

crimes = pd.read_csv(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/crimes-in-boston/crimes-in-boston/crime.csv",

encoding="latin-1",

)

# drop rows with missing locations

crimes.dropna(subset=["Lat", "Long", "DISTRICT"], inplace=True)

# focus on major crimes in 2018

crimes = crimes[

crimes["OFFENSE_CODE_GROUP"].isin(

[

"Larceny",

"Auto Theft",

"Robbery",

"Larceny From Motor Vehicle",

"Residential Burglary",

"Simple Assault",

"Harassment",

"Ballistics",

"Aggravated Assault",

"Other Burglary",

"Arson",

"Commercial Burglary",

"HOME INVASION",

"Homicide",

"Criminal Harassment",

"Manslaughter",

]

)

]

crimes = crimes[crimes["YEAR"] == 2018]

# focus on daytime robberies

daytime_robberies = crimes[

((crimes["OFFENSE_CODE_GROUP"] == "Robbery") & (crimes["HOUR"].isin(range(9, 18))))

]In this tutorial, you'll learn how to create interactive maps with the folium package. We create the base map with folium.Map().

# create the base map

from folium import Map

base_map = Map(location=[42.32, -71.0589], tiles="openstreetmap", zoom_start=10)locationsets the initial center of the map. We use the latitude (42.32° N) and longitude (-71.0589° E) of the city of Boston.tileschanges the styling of the map; in this case, we choose the OpenStreetMap style. If you're curious, you can find the other options listed here.zoom_startsets the initial level of zoom of the map, where higher values zoom in closer to the map.

We add markers to the map with folium.Marker(). Each marker below corresponds to a different robbery.

# define the base map

map_marker = map_base

# add points to the map

from folium import Marker

for idx, row in daytime_robberies.iterrows():

Marker([row["Lat"], row["Long"]], popup=row["HOUR"]).add_to(map_marker)

# display the map

map_markerIf we have a lot of markers to add, folium.plugins.MarkerCluster() can help to declutter the map. Each marker is added to a MarkerCluster object.

# define the base map

map_cluser = map_base

# add points to the map

from folium.plugins import MarkerCluster

mc = MarkerCluster()

from folium import Marker

import math

for idx, row in daytime_robberies.iterrows():

if not math.isnan(row["Lat"]) and not math.isnan(row["Long"]):

mc.add_child(Marker([row["Lat"], row["Long"]]))

map_cluser.add_child(mc)

# display the map

map_cluser- We used

math.isnan()becauserow["Lat"]orrow["Long"]arefloat.

A bubble map uses circles instead of markers. By varying the size and color of each circle, we can also show the relationship between location and two other variables.

We create a bubble map by using folium.Circle() to iteratively add circles.

# define the base map

map_bubble = map_base

# define color/size producer function

def color_producer(val):

if val <= 12:

# robberies that occurred in hours 9-12

return "forestgreen"

else:

# robberies from hours 13-17

return "darkred"

# add a bubble map to the base map

from folium import Circle

for i in range(len(daytime_robberies)):

Circle(

location=[daytime_robberies.iloc[i]["Lat"], daytime_robberies.iloc[i]["Long"]],

radius=20,

color=color_producer(daytime_robberies.iloc[i]["HOUR"]),

).add_to(map_bubble)

# display the map

map_bubblelocationis a list containing the center of the circle, in latitude and longitude.radiussets the radius of the circle.- We can implement this by defining a function similar to the

color_producer()function that is used to vary the color of each circle.

- We can implement this by defining a function similar to the

colorsets the color of each circle.The color_producer()function is used to visualize the effect of the hour on robbery location.

To create a heatmap, we use folium.plugins.HeatMap(). This shows the density of crime in different areas of the city, where red areas have relatively more criminal incidents.

# define the base map

map_heat = map_base

# add a heatmap to the base map

from folium.plugins import HeatMap

HeatMap(data=crimes[["Lat", "Long"]], radius=10).add_to(map_heat)

# display the map

map_heatdatais a DataFrame containing the locations that we'd like to plot.radiuscontrols the smoothness of the heatmap. Higher values make the heatmap look smoother.

To understand how crime varies by police district, we'll create a choropleth map. To create a choropleth, we use folium.Choropleth().

As a first step, we create a GeoDataFrame where each district is assigned a different row, and the geometry column contains the geographical boundaries.

# create GeoDataFrame with geographical boundaries of districts

import geopandas as gpd

districts_full = gpd.read_file(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/Police_Districts/Police_Districts/Police_Districts.shp"

)

districts = districts_full[["DISTRICT", "geometry"]].set_index("DISTRICT")# create a Pandas Series shows the number of crimes in each police district

plot_dict = crimes["DISTRICT"].value_counts()- It's very important that

plot_dicthas the same index as districts - this is how the code knows how to match the geographical boundaries with appropriate colors.

# define the base map

map_choropleth = map_base

# add a choropleth map to the base map

from folium import Choropleth

Choropleth(

geo_data=districts.__geo_interface__,

data=plot_dict,

key_on="feature.id",

fill_color="YlGnBu",

legend_name="Major Criminal Incidents (Jan-Aug 2018)",

).add_to(map_choropleth)

# display the map

map_choroplethgeo_datais a GeoJSON FeatureCollection containing the boundaries of each geographical area.- We convert the districts GeoDataFrame to a GeoJSON FeatureCollection with the

__geo_interface__attribute.

- We convert the districts GeoDataFrame to a GeoJSON FeatureCollection with the

datais a Pandas Series containing the values that will be used to color-code each geographical area.key_onwill always be set tofeature.id, based on the GeoJSON structure.fill_colorsets the color scale.

Find locations with just the name of a place. And, learn how to join data based on spatial relationships. #

Geocoding is the process of converting the name of a place or an address to a location on a map. We'll use geopandas.tools.geocode() to do all of our geocoding.

from geopandas.tools import geocode

geocode("The Great Pyramid of Giza", provider="nominatim")To use the geocoder, we need:

- the

nameoraddressas a Python string, and - the name of the

provider. To avoid having to provide an API key, we used the OpenStreetMap Nominatim geocoder.

It's often the case that we'll need to geocode many different addresses.

# load Starbucks locations in California

import pandas as pd

starbucks = pd.read_csv("../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/starbucks_locations.csv")# define geocoder function

def my_geocoder(row):

try:

point = geocode(row, provider="nominatim")["geometry"][0]

return pd.Series({"Latitude": point.y, "Longitude": point.x})

except:

return NoneIf the geocoding is successful, it returns a GeoDataFrame with two columns:

- the

geometrycolumn, which is aPointobject, and we can get theLatitudeandLongitudefrom theyandxattributes, respectively. - the

addresscolumn contains the full address.

When geocoding a large dataframe, you might encounter an error when geocoding.

- In case you get a time out error, try first using the

timeoutparameter (allow the service a bit more time to respond). - In case of Too Many Requests error, you have hit the rate-limit of the service, and you should slow down your requests.

GeoPyprovides additional tools for taking into account rate limits in geocoding services. More info.

# rows with missing locations

rows_with_missing = starbucks[

starbucks["Latitude"].isna() | starbucks["Longitude"].isna()

]# fill missing geo data

rows_with_missing = rows_with_missing.apply(lambda x: my_geocoder(x["Address"]), axis=1)

# drop rows that were not successfully geocoded

rows_with_missing.dropna(axis=0, subset=["Latitude", "Longitude"])

# update main DataFrame

starbucks.update(rows_with_missing)We can combine data from different sources.

You already know how to use pd.DataFrame.join() to combine information from multiple DataFrames with a shared index. We refer to this way of joining data (by simpling matching values in the index) as an attribute join. We'll work with some DataFrames containing data and a unique id (in the GEOID column) for each county in the state of California.

# create DataFrame contains an estimate of the population of each county

CA_pop = pd.read_csv(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/CA_county_population.csv", index_col="GEOID"

)

# create DataFrame contains the number of households with high income

CA_high_earners = pd.read_csv(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/CA_county_high_earners.csv",

index_col="GEOID",

)

# create DataFrame contains the median age for each county

CA_median_age = pd.read_csv(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/CA_county_median_age.csv", index_col="GEOID"

)# use an attribute join

cols_to_add = CA_pop.join([CA_high_earners, CA_median_age]).reset_index()When performing an attribute join with a GeoDataFrame, it's best to use the gpd.GeoDataFrame.merge(). We'll work with a GeoDataFrame CA_counties containing the name, area (in square kilometers), and a unique id (in the GEOID column) for each county in the state of California. The geometry column contains a polygon with county boundaries.

import geopandas as gpd

CA_counties = gpd.read_file(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/CA_county_boundaries/CA_county_boundaries/CA_county_boundaries.shp"

)# use an attribute join

CA_stats = CA_counties.merge(cols_to_add, on="GEOID")- The

onargument is set to the column name that is used to match rows.

Now that we have all of the data in one place, it's much easier to calculate statistics that use a combination of columns.

CA_stats["density"] = CA_stats["population"] / CA_stats["area_sqkm"]With a spatial join, we combine GeoDataFrames based on the spatial relationship between the objects in the geometry columns. We do this with gpd.sjoin().

So, which counties look promising for new Starbucks Reserve Roastery?

sel_counties = CA_stats[

(CA_stats["high_earners"] >= 100000)

& (CA_stats["median_age"] <= 38.5)

& (CA_stats["density"] >= 285)

]

sel_counties.crs = {"init": "epsg:4326"}starbucks_gdf = gpd.GeoDataFrame(

starbucks,

geometry=gpd.points_from_xy(starbucks["Longitude"], starbucks["Latitude"]),

)

starbucks_gdf.crs = {"init": "epsg:4326"}sel_counties_stores = gpd.sjoin(starbucks_gdf, sel_counties)The spatial join above looks at the geometry columns in both GeoDataFrames. If a Point object from the starbucks_gdf GeoDataFrame intersects a Polygon object from the sel_counties DataFrame, the corresponding rows are combined and added as a single row of the sel_counties_stores DataFrame. Otherwise, counties without a matching starbuckses (and starbuckses without a matching county) are omitted from the results.

The gpd.sjoin() method is customizable for different types of joins, through the how and op arguments. For example, you can do the equivalent of a SQL left (or right) join by setting how='left' (or how='right').

Let's visualize!

# define the base map

from folium import Map

map_cluser = Map(location=[37, -120], zoom_start=6)

# add points to the map

from folium.plugins import MarkerCluster

mc = MarkerCluster()

from folium import Marker

for idx, row in sel_counties_stores.iterrows():

mc.add_child(Marker([row["Latitude"], row["Longitude"]]))

map_cluser.add_child(mc)

# display the map

map_cluserMeasure distance, and explore neighboring points on a map. #

We'll explore several techniques for proximity analysis, such as:

- Measuring the distance between points on a map, and

- Selecting all points within some radius of a feature.

We want to identify how hospitals have been responding to crash collisions in New York City. We'll work with GeoDataFrame collisions tracking major motor vehicle collisions in 2013-2018.

import geopandas as gpd

collisions = gpd.read_file(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/NYPD_Motor_Vehicle_Collisions/NYPD_Motor_Vehicle_Collisions/NYPD_Motor_Vehicle_Collisions.shp"

)

hospitals = gpd.read_file(

"../input/geospatial-learn-course-data/nyu_2451_34494/nyu_2451_34494/nyu_2451_34494.shp"

)To measure distances between points from two different GeoDataFrames, we first have to make sure that they use the same CRS.

collisions.crs == hospitals.crs- We also check the CRS to see which units it uses (meters, feet, or something else). In this case, EPSG 2263 has units of meters.

Then, we use the distance() method, returns a Series containing the distance to the others.

# measure distance from a relatively recent collision to each hospital

distances = hospitals["geometry"].distance(collisions.iloc[-1]["geometry"])# calculate mean distance to hospitals

distances.mean()

# find the closest hospital

hospitals.iloc[distances.idxmin()][["ADDRESS", "LATITUDE", "LONGITUDE"]]If we want to understand all points on a map that are some radius away from a point, the simplest way is to create a buffer. It's a GeoSeries containing multiple Polygon objects. Each polygon is a buffer around a different spot.

We'll create a DataFrame outside_range containing all rows from collisions with crashes that occurred more than 10 kilometers from the closest hospital.

# create a GeoSeries buffer

ten_km_buffer = hospitals["geometry"].buffer(10000)To test if a collision occurred within 10 kilometers of any hospital, we could run different tests for each polygon. But a more efficient way is to first collapse all of the polygons into a MultiPolygon object. We do this with the unary_union attribute.

# turn group of polygons into single multipolygon

my_union = ten_km_buffer.unary_unionWe use the contains() method to check if the multipolygon contains a point.

# is the closest station less than two miles away?

my_union.contains(collisions.iloc[-1]["geometry"])outside_range = collisions.loc[

~collisions["geometry"].apply(lambda x: my_union.contains(x))

]# calculate the percentage of collisions occurred more than 10 km away from the closest hospital

round(100 * len(outside_range) / len(collisions), 2)When collisions occur in distant locations, it becomes even more vital that injured persons are transported to the nearest available hospital.

With this in mind, we want to create a recommender that:

- takes the location of the crash as input,

- finds the closest hospital, and

- returns the name of the closest hospital.

def best_hospital(collision_location):

idx_min = hospitals["geometry"].distance(collision_location).idxmin()

return hospitals.iloc[idx_min]["name"]# suggest the closest hospital to the last collision

best_hospital(outside_range["geometry"].iloc[-1])# which hospital is most recommended?

outside_range["geometry"].apply(best_hospital).value_counts().idxmax()Where should the city construct new hospitals? Lets visualize!

# define the base map

from folium import Map

m = Map(location=[40.7, -74], zoom_start=11)

# add buffers' Polygon

from folium import GeoJson

GeoJson(ten_km_buffer.to_crs(epsg=4326)).add_to(m)

# add the heatmap of collisions, out of 10km buffers

from folium.plugins import HeatMap

HeatMap(data=outside_range[["LATITUDE", "LONGITUDE"]], radius=9).add_to(m)

# add (Lat,Long) popup

from folium import LatLngPopup

LatLngPopup().add_to(m)

# display the map

m- We use

folium.GeoJson()to plot eachPolygonon a map. Note that since folium requires coordinates in latitude and longitude, we have to convert the CRS to EPSG 4326 before plotting.

Learn the core ideas in machine learning, and build your first models.

The first step if you're new to machine learning. #

- Fitting or Training: Capturing patterns from training data

- Predicting: Getting results from applying the model to new data

Load and understand your data. #

# load data

import pandas as pd

melbourne_data = pd.read_csv("../input/melbourne-housing-snapshot/melb_data.csv")# summary

melbourne_data.head()

melbourne_data.describe()Building your first model. Hurray! #

# filter rows with missing values

dropna_melbourne_data = melbourne_data.dropna(axis=0)# separate target (y) from features (predictors, X)

y = dropna_melbourne_data["Price"]

feature_list = [

"Rooms",

"Bathroom",

"Landsize",

"BuildingArea",

"YearBuilt",

"Lattitude",

"Longtitude",

]

X = dropna_melbourne_data[feature_list]- Define: What type of model will it be? A decision tree? Some other type of model?

- Fit: Capture patterns from provided data. This is the heart of modeling.

- Predict: Just what it sounds like.

- Evaluate: Determine how accurate the model's predictions are.

# define model

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeRegressor

melbourne_model = DecisionTreeRegressor(random_state=1)

# fit model

melbourne_model.fit(X, y)

# make prediction

predictions = melbourne_model.predict(X)Measure the performance of your model? So you can test and compare alternatives. #

There are many metrics for summarizing the model quality. Predictive accuracy means will the model's predictions be close to what actually happens?

Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

from sklearn.metrics import mean_absolute_error

mean_absolute_error(y, predictions)Big Mistake: Measuring scores with the training data or the problem with in-sample scores!

Making predictions on new data

Exclude some data from the model-building process, and then use those to test the model's accuracy.

# break off validation set from training data, for both features and target

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train, X_valid, y_train, y_valid = train_test_split(X, y, random_state=1)# define model

melbourne_model = DecisionTreeRegressor(random_state=1)

# fit model

melbourne_model.fit(X_train, y_train)

# make prediction on validation data

predictions_val = melbourne_model.predict(X_valid)

# evaluate the model

mean_absolute_error(y_valid, predictions_val)There are many ways to improve a model, such as

- Finding better features, the iterating process of building models with different features and comparing them to each other

- Finding better model types

Fine-tune your model for better performance. #

- Overfitting: Capturing spurious patterns that won't recur in the future, leading to less accurate predictions.

- Underfitting: Failing to capture relevant patterns, again leading to less accurate predictions.

In the Decision Tree model, the most important option to control the accuracy is the tree's depth, a measure of how many splits it makes before coming to a prediction.

- A deep tree makes leaves with fewer objects. It causes overfitting.

- A shallow tree makes big groups. It causes underfitting.

There are a few options for controlling the tree depth, and many allow for some routes through the tree to have greater depth than other routes. But the max_leaf_nodes argument provides a very sensible way to control overfitting vs underfitting.

# function for comparing MAE with differing values of max_leaf_nodes

def get_mae(max_leaf_nodes, X_train, X_valid, y_train, y_valid):

model = DecisionTreeRegressor(max_leaf_nodes=max_leaf_nodes, random_state=0)

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

predictions_val = model.predict(X_valid)

mae = mean_absolute_error(y_valid, predictions_val)

return mae# compare models

max_leaf_nodes_candidates = [5, 50, 500, 5000]

scores = {

leaf_size: get_mae(leaf_size, X_train, X_valid, y_train, y_valid)

for leaf_size in max_leaf_nodes_candidates

}

best_tree_size = min(scores, key=scores.get)Using a more sophisticated machine learning algorithm. #

Decision trees leave you with a difficult decision. A deep tree and overfitting vs. a shallow one and underfitting.

A Random Forest model uses many trees, and makes a prediction by averaging the predictions of each component. It generally has much better predictive accuracy even with than a single decision tree, even with default parameters, without tuning the parameters like max_leaf_nodes.

# define & fit model

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

forest_model = RandomForestRegressor(random_state=1)

forest_model.fit(X_train, y_train)

# make prediction

preds_valid = forest_model.predict(X_valid)

# evaluate the model

from sklearn.metrics import mean_absolute_error

mean_absolute_error(y_valid, preds_valid)Some models, like the XGBoost model, provides better performance when tuned well with the right parameters (but which requires some skill to get the right model parameters).

Enter the world of machine learning competitions to keep improving and see your progress. #

# load data

import pandas as pd

X_full = pd.read_csv("../input/train.csv", index_col="Id")

X_test_full = pd.read_csv("../input/test.csv", index_col="Id")# separate target (y) from features (X)

y = X_full["SalePrice"]

features = [

"LotArea",

"YearBuilt",

"1stFlrSF",

"2ndFlrSF",

"FullBath",

"BedroomAbvGr",

"TotRmsAbvGrd",

]

X = X_full[features].copy()

X_test = X_test_full[features].copy()# break off validation set from training data

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train, X_valid, y_train, y_valid = train_test_split(

X, y, train_size=0.8, test_size=0.2, random_state=0

)# define models

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeRegressor

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

model_1 = DecisionTreeRegressor(random_state=0)

model_2 = DecisionTreeRegressor(max_leaf_nodes=100, random_state=0)

model_3 = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=50, random_state=0)

model_4 = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=100, random_state=0)

model_5 = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=100, criterion="mae", random_state=0)

model_6 = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=200, min_samples_split=20, random_state=0)

model_7 = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=100, max_depth=7, random_state=0)

models = [model_1, model_2, model_3, model_4, model_5, model_6, model_7]# function for comparing different models

from sklearn.metrics import mean_absolute_error

def score_model(model, X_train, X_valid, y_train, y_valid):

# fit model

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

# make validation predictions

preds_valid = model.predict(X_valid)

# return mae

return mean_absolute_error(y_valid, preds_valid)# compare models

for i in range(len(models)):

mae = score_model(models[i])

print(f"Model {i+1} MAE: {mae:,.0f}")Model 1 MAE: 29,653

Model 2 MAE: 27,283

Model 3 MAE: 24,015

Model 4 MAE: 23,740

Model 5 MAE: 23,528

Model 6 MAE: 23,996

Model 7 MAE: 23,706# define model, based on the most accurate model

my_model = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=100, criterion="mae", random_state=0)

# fit the model to the training data, all of it

my_model.fit(X, y)

# make test prediction

preds_test = my_model.predict(X_test)# save predictions in format used for competition scoring

output = pd.DataFrame({"Id": X_test.index, "SalePrice": preds_test})

output.to_csv("submission.csv", index=False)Learn to handle missing values, non-numeric values, data leakage and more. Your models will be more accurate and useful.

Review what you need for this Micro-Course. #

In this micro-course, you will accelerate your machine learning expertise by learning how to:

- Tackle data types often found in real-world datasets (missing values, categorical variables),

- Design pipelines to improve the quality of your machine learning code,

- Use advanced techniques for model validation (cross-validation),

- Build state-of-the-art models that are widely used to win Kaggle competitions (XGBoost), and

- Avoid common and important data science mistakes (leakage).

Missing values happen. Be prepared for this common challenge in real datasets. #

There are many ways data can end up with missing values. For example,

- A 2 bedroom house won't include a value for the size of a third bedroom.

- A survey respondent may choose not to share his income.

Most machine learning libraries (including scikit-learn) give an error if you try to build a model using data with missing values.

# show number of missing values in each column

def missing_val_count(data):

missing_val_count_by_column = data.isna().sum()

return missing_val_count_by_column[missing_val_count_by_column > 0]- Drop Columns with Missing Values

- Imputation

# load data

import pandas as pd

X_full = pd.read_csv("../input/train.csv", index_col="Id")

X_test_full = pd.read_csv("../input/test.csv", index_col="Id")# remove rows with missing "SalePrice"

X_full.dropna(axis=0, subset=["SalePrice"], inplace=True)# separate target (y) from features (X)

y = X_full["SalePrice"]

X_full.drop(["SalePrice"], axis=1, inplace=True)# use only numerical features, to keep things simple

X = X_full.select_dtypes(exclude=["object"])

X_test = X_test_full.select_dtypes(exclude=["object"])# break off validation set from training data

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train, X_valid, y_train, y_valid = train_test_split(

X, y, train_size=0.8, test_size=0.2, random_state=0

)# get names of columns with missing values

cols_with_missing = [col for col in X_train.columns if X_train[col].isna().any()]# function for comparing different approaches

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.metrics import mean_absolute_error

def score_dataset(X_train, X_valid, y_train, y_valid):

model = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=10, random_state=0)

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

preds_valid = model.predict(X_valid)

return mean_absolute_error(y_valid, preds_valid)The model loses access to a lot of (potentially useful!) information with this approach.

# drop `cols_with_missing` in training and validation data

reduced_X_train = X_train.drop(cols_with_missing, axis=1)

reduced_X_valid = X_valid.drop(cols_with_missing, axis=1)

# evaluate the model

score_dataset(reduced_X_train, reduced_X_valid, y_train, y_valid)Imputation fills in the missing values with some number.

# imputation

from sklearn.impute import SimpleImputer

imputer = SimpleImputer(strategy="mean")

imputed_X_train = pd.DataFrame(imputer.fit_transform(X_train))

imputed_X_valid = pd.DataFrame(imputer.transform(X_valid))

# imputation removed column names; put them back

imputed_X_train.columns = X_train.columns

imputed_X_valid.columns = X_valid.columns

# evaluate the model

score_dataset(imputed_X_train, imputed_X_valid, y_train, y_valid)Strategy

- default=

meanreplaces missing values using the mean along each column. (only numeric) medianreplaces missing values using the median along each column. (only numeric)most_frequentreplaces missing using the most frequent value along each column. (strings or numeric)constantreplaces missing values withfill_value. (strings or numeric)

# define and fit model

model = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=100, random_state=0)

model.fit(imputed_X_train, y_train)

# make validation prediction

preds_valid = model.predict(imputed_X_valid)

mean_absolute_error(y_valid, preds_valid)# preprocess test data

imputed_X_test = pd.DataFrame(imputer.fit_transform(X_test))

# put column names back

imputed_X_test.columns = X_test.columns

# make test prediction

preds_test = model.predict(imputed_X_test)# save test predictions to file

output = pd.DataFrame({"Id": X_test.index, "SalePrice": preds_test})

output.to_csv("submission.csv", index=False)There's a lot of non-numeric data out there. Here's how to use it for machine learning. #

A categorical variable takes only a limited number of values.

- Ordinal: A question that asks "how often you eat breakfast?" and provides four options: "Never", "Rarely", "Most days", or "Every day".

- Nominal: A question that asks "what brand of car you own?".

Most machine learning libraries (including scikit-learn) give an error if you try to build a model using data with categorical variables.

- Drop Categorical Variables

- Label Encoding

- One-Hot Encoding

# load data

import pandas as pd

X_full = pd.read_csv("../input/train.csv", index_col="Id")

X_test_full = pd.read_csv("../input/test.csv", index_col="Id")# remove rows with missing target

X_full.dropna(axis=0, subset=["SalePrice"], inplace=True)# separate target (y) from features (X)

y = data["Price"]

X = data.drop(["Price"], axis=1)# break off validation set from training data

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train_full, X_valid_full, y_train, y_valid = train_test_split(

X, y, train_size=0.8, test_size=0.2, random_state=0

)# handle missing values (simplest approach)

cols_with_missing = [

col for col in X_train_full.columns if X_train_full[col].isna().any()

]

X_train_full.drop(cols_with_missing, axis=1, inplace=True)

X_valid_full.drop(cols_with_missing, axis=1, inplace=True)# select categorical columns with relatively low cardinality, to keep things simple

# cardinality means the number of unique values in a column

categorical_cols = [

cname

for cname in X_train_full.columns

if (X_train_full[cname].dtype == "object") and (X_train_full[cname].nunique() < 10)

]

# select numerical columns

numerical_cols = [

cname

for cname in X_train_full.columns

if X_train_full[cname].dtype in ["int64", "float64"]

]

# keep selected columns only

my_cols = categorical_cols + numerical_cols

X_train = X_train_full[my_cols].copy()

X_valid = X_valid_full[my_cols].copy()

X_test = X_test_full[my_cols].copy()# function for comparing different approaches

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.metrics import mean_absolute_error

def score_dataset(X_train, X_valid, y_train, y_valid):

model = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=100, random_state=0)

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

preds = model.predict(X_valid)

return mean_absolute_error(y_valid, preds)This approach will only work well if the columns did not contain useful information.

# drop catagorial columns

drop_X_train = X_train.select_dtypes(exclude=["object"])

drop_X_valid = X_valid.select_dtypes(exclude=["object"])

# evaluate the model

score_dataset(drop_X_train, drop_X_valid, y_train, y_valid)Label encoding assigns each unique value, that appears in the training data, to a different integer.

In the case that the validation data contains values that don't also appear in the training data, the encoder will throw an error, because these values won't have an integer assigned to them. It should be used only for target labels encoding.

To encode categorical features, use One-Hot Encoder, which can handle unseen values.

For tree-based models (like decision trees and random forests), you can expect label encoding to work well with ordinal variables.

# find columns, which are in validation data but not in training data

good_label_cols = [

col for col in categorical_cols if set(X_train[col]) == set(X_valid[col])

]

bad_label_cols = list(set(categorical_cols) - set(good_label_cols))

# drop them

label_X_train = X_train.drop(bad_label_cols, axis=1)

label_X_valid = X_valid.drop(bad_label_cols, axis=1)

# apply label encoder

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder

label_encoder = LabelEncoder()

for col in good_label_cols:

label_X_train[col] = label_encoder.fit_transform(X_train[col])

label_X_valid[col] = label_encoder.transform(X_valid[col])

# evaluate the model

score_dataset(label_X_train, label_X_valid, y_train, y_valid)One-hot encoding creates new columns indicating the presence (or absence) of each possible value in the original data. Useful parameters are:

handle_unknown="ignore"avoids errors when the validation data contains classes that aren't represented in the training data,sparse=Falsereturns the encoded columns as a numpy array (instead of a sparse matrix).

In contrast to label encoding, one-hot encoding does not assume an ordering of the categories. Thus, you can expect this approach to work particularly well with categorical variables without an intrinsic ranking, we refer them as nominal variables.

One-hot encoding generally does not perform well with high-cardinality categorical variable (i.e., more than 15 different values). Cardinality means the number of unique values in a column.

# get cardinality for each column with categorical data

object_nunique = list(map(lambda col: X_train[col].nunique(), categorical_cols))

d = dict(zip(categorical_cols, object_nunique))

# print cardinality by column, in ascending order