Work performed at Indiana University, GTAP program 2019

We are working with Pi language. Pi is a language for describing (syntactically) invertible functions between types. It consists of three parts:

- First part is about types. It consists of type constants

0, 1and type constructors_+_ , _*_ - Second part is about invertible functions between these types. It consists of so-called 1-combinators: constants (like

id: A <-> A,+-comm: A + B <-> B + A, etc.) and 1-combinators constructors (like sequential composition, parallel composition etc). - Third part is about the equivalences between the 1-combinators, so called 2-combinators (like

id-left: id.x <=> x, etc).

To define the semantics of Pi, we have to map Pi types to appropriate concrete types, where 1-combinators will be mapped to bijections between (concrete) types, and if two 1-combinators are related by some 2-combinator, then appropriate (concrete) bijections should be equivalent.

We'd also like this language to be complete in this context, e.g. for the family of concrete types that we can get from interpreting Pi types, every possible bijection can be acquired by interpreting some 1-combinator, and if two bijections are equivalent, there is a way of constructing 2-combinator between them.

To do that, the choice was made to have the semantics grounded in (... - this depends on where does Robert Rose work - in HoTT? in pure Agda? in cubical?)

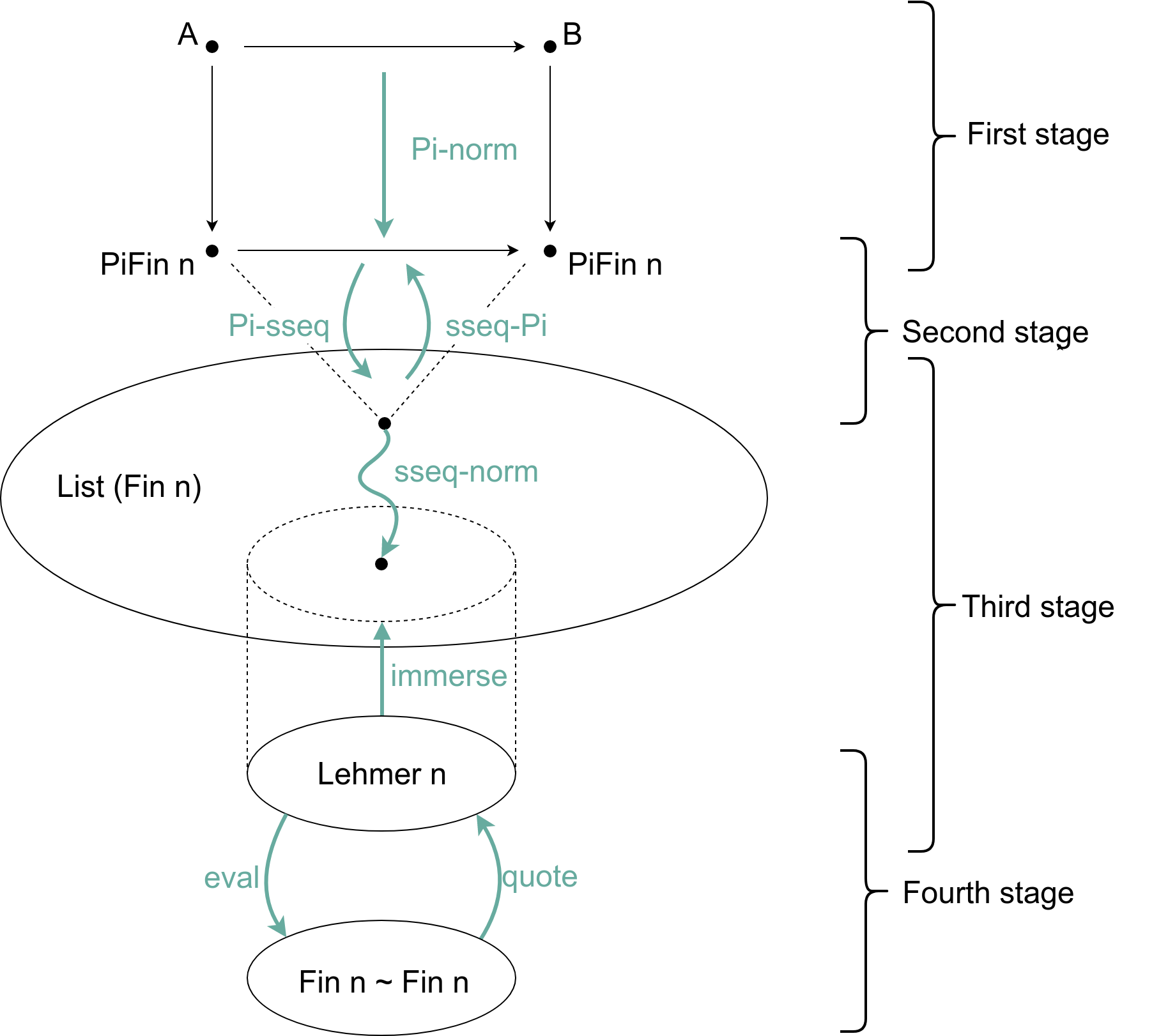

The proof is done in four stages.

-

The first step is doing an internal normalization in Pi. This includes types normalization (informally speaking, every type in Pi should be "equivalent" to a type in the family

PiFin = {0, 0 + 1, (0 + 1) + 1, ((0 + 1) + 1) + 1, ...}) and 1-combinator normalization (we want to our normalized combinators to be built solely out ofid, assoc, swapconstants and sequential and parallel composition). In the end, we should have the functionPi-norm : {A B : Pi-type} -> (c : A <-> B) -> Σ ℕ (λ n -> Σ ( PiFin n <-> PiFin n) (λ cc -> c <=> cn))

-

Then, in the next step, we want to switch away from Pi, and talk about the combinators more abstractly - informally, as seqences of adjecent swaps (we'll talk about it in the next section). Such sequences are represented as elements of the

List (Fin n)type. So, we'd like to have two functionsPi-sseq : {n : ℕ} -> (c : PiFin n <-> PiFin n) -> List (Fin n) sseq-Pi : {n : ℕ} -> List ℕ -> (PiFin n <-> PiFin n)

along with the proofs that

Pi-sseq ∘ sseq-Pi ≡ idandsseq-Pi ∘ Pi-sseq ≡ id. -

In the third step, we're in the realm of permutations represented as

List (Fin n)- in other words, what we have is a word in the free group ofngenerators. We introduce a relation_≃_, based on Coxeter presentation of full symmetric groupS_n(where the generators are elements ofFin n- thek-th generator represents a transposition ofk-th andk+1-th elements), and we'd like to show that the typeList (Fin n)divided by this equivalence relation is isomorphic to yet another form of permutation representation - Lehmer codes.

We do that by defining a functionimmerse : {n : ℕ} -> Lehmer n -> List (Fin n)

(together with a proof that it is an injection), and a proof

sseq-norm : {n : ℕ} -> (l : List (Fin n)) -> Σ (Lehmer n) (λ cl -> l ≃ cl)

-

As a fourth step, we do the final isomorphism, between Lehmer codes and real bijections. Having the type of bijections as

_~_, what we want are two functionseval : {n : ℕ} -> (Lehmer n) -> (Fin n ~ Fin n) quote : {n : ℕ} -> (Fin n ~ Fin n) -> (Lehmer n)

along with the proofs that

eval ∘ quote ≡ idandquote ∘ eval ≡ id.

We can then finally define

Pi-eval = eval ∘ sseq-norm ∘ Pi-sseq ∘ Pi-norm

quote-Pi = sseq-Pi ∘ immerse ∘ quote`and two proofs

- that turning an bijection into a 1-combinator and executing it gives us the same bijection back:

quote-eval : Pi-eval ∘ quote-Pi ≡ id - that executing a 1-combinator and then quoting the result gives us the same (with respect to 2-combinators) combinator back:

eval-quote : {A B : PiType} -> (c : A <-> B) -> ((quote-Pi ∘ Pi-eval) c) <=> c

The picture below hopefully shows the whole process more clearly

The reason the proof is structured in a way it is, is to bring down the complexity of idividual steps.

First, as Pi is a fairly complicated language, with many features built-in, we want to scale it down to the bare minimum. This minimum consists specifically of the standard types (0 + 1 + 1 + ...) and functions defined by id, assoc, swap together with parallel and sequential composition.

Then, we go to even more bare-bones, abstract language for describing permutations syntactically - lists of numbers denoting adjecent swaps - based on Coxeter presentation of a full symmetric group S_n. It is in this setting we isolate the task of word normalization (e.g. reducing all words to a subset of them).

This step takes us from the countable to the finite world (intuitively, from "operational" to "denotational" world). In the first one, each permutation is written as a sequence of operations, and so the type representing the permutations (on some particular type) is infinite - in the second one, we have some finite representation of this set of permutations, and permutations having the same "outcome" are identified.

The choice of introducing this intermediate representation in terms of Lehmer codes stems from the fact that working with the bijections type in Agda is a little cumbersome - they are defined as invertible functions, having the proofs of compositions with inversions being identity and so on. The Lehmer codes do not come with any of that - in a way, they are the simplest possible way of talking about the type of bijections on a finite type - and, in addition, have a very natural embedding as words in List (Fin n).

Having the Lehmer encoding of the bijection, we can isolate the complexity of dealing with bijection types in the last stage of the proof.

Since every step comes with it's own proofs of being an isomorphism (in case of step 3 - injection), the whole proof can be made by composition of all parts.

Info from prof. Sabry.

Info from prof. Sabry.

We can define Coxeter presentation in Agda as follows (this will be useful later on):

data _≃_ : List ℕ -> List ℕ -> Set where

cancel : l ++ n ∷ n ∷ r ≃ l ++ r

swap : {k : ℕ} -> (suc k < n) -> l ++ n ∷ k ∷ r ≃ l ++ k ∷ n ∷ r

braid : l ++ (suc n) ∷ n ∷ (suc n) ∷ r ≃ l ++ n ∷ (suc n) ∷ n ∷ r

refl : m ≃ m

comm : m1 ≃ m2 -> m2 ≃ m1

trans : m1 ≃ m2 -> m2 ≃ m3 -> m1 ≃ m3In our case, the normalization is done using a collection of the following rewriting rules:

cancel, wherel ++ n ∷ n ∷ rgoes tol ++ rswap, wherel ++ k ∷ n ∷ rgoes tol ++ n ∷ k ∷ r, provided that1 + k < nlbraid, wherel ++ n ∷ n - 1 ∷ n - 2 ∷ ... ∷ n - k ∷ n ∷ rgoes tol ++ n - 1 ∷ n ∷ n - 2 ∷ ... ∷ n - k ∷ r, provided that0 < k

These three rules come from Coxeter presentation, and the first two of them appear verbatim. The third rule is different - it replaces the standard braid rule.

Using these rewriting rules, after taking reflexive-transitive closure, we prove the

- Local confluence - this is the main technical result of this section. The proof requires resolving all critical pairs and is quite long.

- Strong normalization - this stems from the fact that each transformation either reduces the length of the list or its lexicographical order.

- Church-Rosser - this is the classic, short proof by induction on the reflexive-transitive closure of the reduction rules.

This whole procedure is done to define the relation

data _≃_ : List ℕ -> List ℕ -> Set where

comm : (l1 l2 l : List ℕ) -> (l1 →* l) -> (l2 →* l) -> l1 ≃ l2Contrast this with the usual definition of Coxeter relations for a full symmetric group, where the reduction rules (having braid instad of lbraid) go in both directions, so there is no normalization property.

Our third rule - lbraid - is defined as such, because it is both strong enough to give the diamond property (ie to resolve critical pairs), and weak enough not to break Coxeter equivalence (we prove formally that the equivalence relation defined above is not stronger than Coxeter relation).

The reason we're using this admittedly more complicated machinery is because it is very hard (or maybe even impossible) to prove certain things about the relation when using non-directed version. For example, suppose that what we need to prove is that [] ≄ [ 0 ]. Using the standard Coxeter presentation, we quickly run into a problem with transitive property: we have to prove, that there is no (arbitrary list) l, such that [] ≃ l and l ≃ [ x ]. Thus, we can't do usual induction over reduction rules, and the only way to prove that is to use some kind of clever invariant. And even though in this particular case, the invariant saying that if l ≃ l', then their lengths are equal mod 2 would suffice, it should be clear that in general case, proving things about this relation is going to be very difficult.

After performing all reductions possible, we arrive at one of the normal forms - in the image of immersion of Lehmer codes. We define them as

data Lehmer : ℕ -> Set where

LZ : Lehmer 0

LS : (l : Lehmer n) -> {r : ℕ} -> (r ≤ suc n) -> Lehmer (suc n)So, Lehmer codes are, in essence, lists, where on n-th place there is a number that is less than or equal to n.

To define embedding, we first define a decreasing sequence

_↓_ : (n : ℕ) -> (k : ℕ) -> List ℕ

n ↓ 0 = []

n ↓ (suc k) = (k + n) ∷ (n ↓ k)By the defintion above, n ↓ (1 + k) means a sequence

[n + k, n + (k - 1), ... n].

Now, we can define immersion as

immersion : {n : ℕ} -> Lehmer n -> List ℕ

immersion {zero} LZ = []

immersion {suc n} (LS l {r} _) = (immersion l) ++ (((suc n) ∸ r) ↓ r)Immersion takes a Lehmer code, interprets the number on n-th place as the length of decreasing sequece starting with n, and then concatenates them all together.

Example immersions of Lehmer codes (the embeddings are our normal forms):

[]goes to[][0, 0, 0]goes to[][1]goes to[0][1, 2]goes to[0, 1, 0][1, 2, 3, 4]goes to[0, 1, 0, 2, 1, 0, 3, 2, 1, 0][1, 0, 0, 3, 2]goes to[0, 3, 2, 1, 0, 4, 3].

In the section above, we prove that any two ways of reducing given word, using provided rules, are equivalent.

A somewhat easier way to define reduction is to focus on some standard reduction method, and prove properties only for that method. This is what Alain Lascoux does in (THE SYMMETRIC GROUP, 2002, unpublished) does, in Lemma 1, and what is (partially) replicated in the Coq proof of the equivalence between Coxeter presentation of S_n and bijections between sets (see https://github.com/hivert/Coq-Combi/blob/master/theories/SymGroup/presentSn.v).

We started by implementing this method first, but then run into technical problems described at the end of the previous section. Although Lascoux method does not require the use of full Coxeter relations, and works with reduction rules described above, we thought it is better to prove the more general case, since we had the machinery set up anyway.

The implementation closely follows the decription in the book (text included?) and is availble in the lascoux directory.

Lascoux method works by induction over the generators, from the highest to the lowest. Let's assume that we are currently at the generator k. There are three reduction rules at our disposition (actually, three reduction schemas, like our lbraid) and the strategy to select next redux is to choose the leftmost redux of all that contain k. If threre is no such thing - proceed with induction. The rules are chosen such that this process always terminates, and always brings one the predefined normal forms (the same as we defined earlier.)

Info from Robert Rose.

An alternative approach to defining isomorphism between Lehmer codes and bijections would be to work directly with lists of transpositions. Then, eval is trivially defined as a composition of eval on each element, and the proof that it gives a bijection is also quite easily done by induction.

On the other hand, quote can be defined as insertion sort of tabulated function values. That this is specifically the insertion sort is important - and that's because normalized words in Coxeter group are precisely the sequences of swaps coming from insertion sort running on some data!

Then, to complete the proof, one would have to show that eval respects Coxeter equations - but it's again quite simple to do so.

As the space of 1-combinators is much bigger than the space of bijections, we cannot hope for getting the same thing back - but this is a good thing! What we are actually getting is a normalized version of the program defined by 1-combinator.

What we would like would be of course an "optimized" version of such a program. The procedure outlined cannot guarantee that at this moment - the reason for this is that we lack the un-norm-Pi function, that would serve as a counterpart of Pi-norm. What we have now is the optimizer for the low-level language describing the permutations (lists of adjecent transpositions) (TODO think more about that) There is an obvious way of embedding lists of transpositions into Pi, but what is unclear is whether this naive embedding, even though being an, is actually "optimal" at the level of Pi - moreover, we don't even have a good notion of what it would mean (some possible choices would be: lowest number of operators, lowest number of sequential steps, etc.).

Of course, it is possible that such a notion will be developed in the future, along with the un-nor-Pi function, ultimately giving us the optimizer for the whole stack.

In general, optimiztion is a hard process. In this case, however, notice that we don't have to optimize arbitrary programs (Pi expressions) - only the normal forms! As normal forms have a very clear, "rigid" structure, the task of writing optimizer for them no longer seems impossibly hard.

In code/AllExports.agda, we include all exported signatures and types.