This work demonstrates the use of PyCuTe to generate constants and integers for an MLIR Python binding-driven code generation solution targeting mlir.nvgpu and mlir.nvvm. PyCuTe is employed to tile, partition, compute descriptor bits, and encode layouts, offsets, and strides essential for code generation. This enhances the coverage, scalability, and composability of NVIDIA codegen solutions. By combining CuTe concepts (layout and layout algebra) with MLIR, all through Python, it brings significant advancements in programmability and user-experience.

AI accelerators like the NVIDIA H100 hierarchically tile large problems through various memory hierarchy to the compute cores (Tensor Cores). This hierarchical approach leads to blocked layouts where different layout modes emerge at various stages, from global memory to shared memory to registers and closer to the Tensor Cores. The logical significance of these modes often gets obscured due to error-prone div-mod math.

CuTe simplifies this by providing Layout and Layout Algebra, enabling the definition and manipulation of hierarchical, multidimensional layouts. This approach elegantly scales solutions by abstracting away complex div-mod math, allowing programmers to retain and exploit the logical significance of these modes.

This section highlights the power of CuTe concepts. PyCuTe provides MLIR Python codegen with significant enhancements. The smallest unit of math tile exposed to programmers on Hopper is wgmma.m64nNk16. However, for effective codegen, tiling needs to be addressed beyond that point. The core matrix 8x8xf16 (highlighted in pink) must be tiled over wgmma.m64nNk16 to obtain the GMMA descriptor bits.

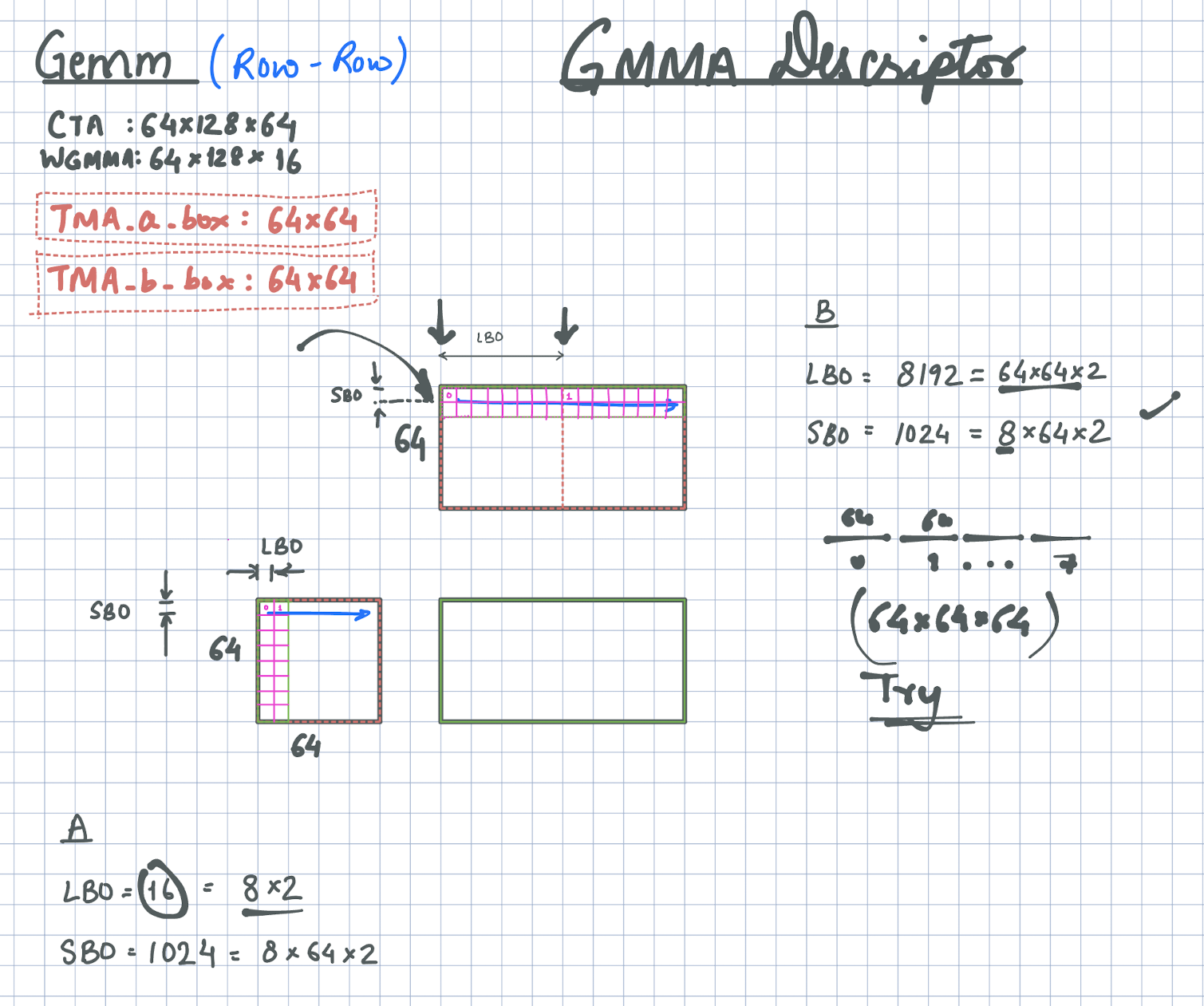

Figure 1 shows the definitions of wgmma descriptors: Leading Byte Offset (LBO) and Stride Byte Offset (SBO), which are crucial in setting the GMMA descriptor bits. The figure illustrates a 64x128x64 CTA tile and a 64x128x16 wgmma Tensor Core, where shared memory tiles are loaded using TMA. LBO represents the byte offset between two core matrices in the contiguous dimension (blue line), while SBO is the byte offset between core matrices in the strided dimension.

Using these definitions, we can apply architecture-specific tiling operations to deduce compile-time integer values for various data types and layouts. Please refer to the PyCuTe [code, test] implemented in this work to understand how the figure converts into integers.

CuTe's layout algebra enables us to transform illustrations into code, code into integers, and integers into codegen, improving scalability, correctness, and user-experience. While it can also enhance code readability, this requires thorough familiarity with the CuTe documentation and practice.

The example above demonstrates how PyCuTe aids in tiling part of a large problem hierarchically to utilize Hopper Tensor Cores. PyCuTe concepts prove valuable in many scenarios. I champion that the software components need to be carefully to target the Hopper and exploit its power to combine different arch features. The CUTLASS/CuTe (CUDA/C++) solution has established a reliable approach to decomposing problems for Hopper Tensor Cores while maximizing performance and scalability. Next, we present code structures built using MLIR Python bindings and PyCuTe (Python), incorporating insights gained from the CUTLASS/CuTe solution in CUDA/C++.

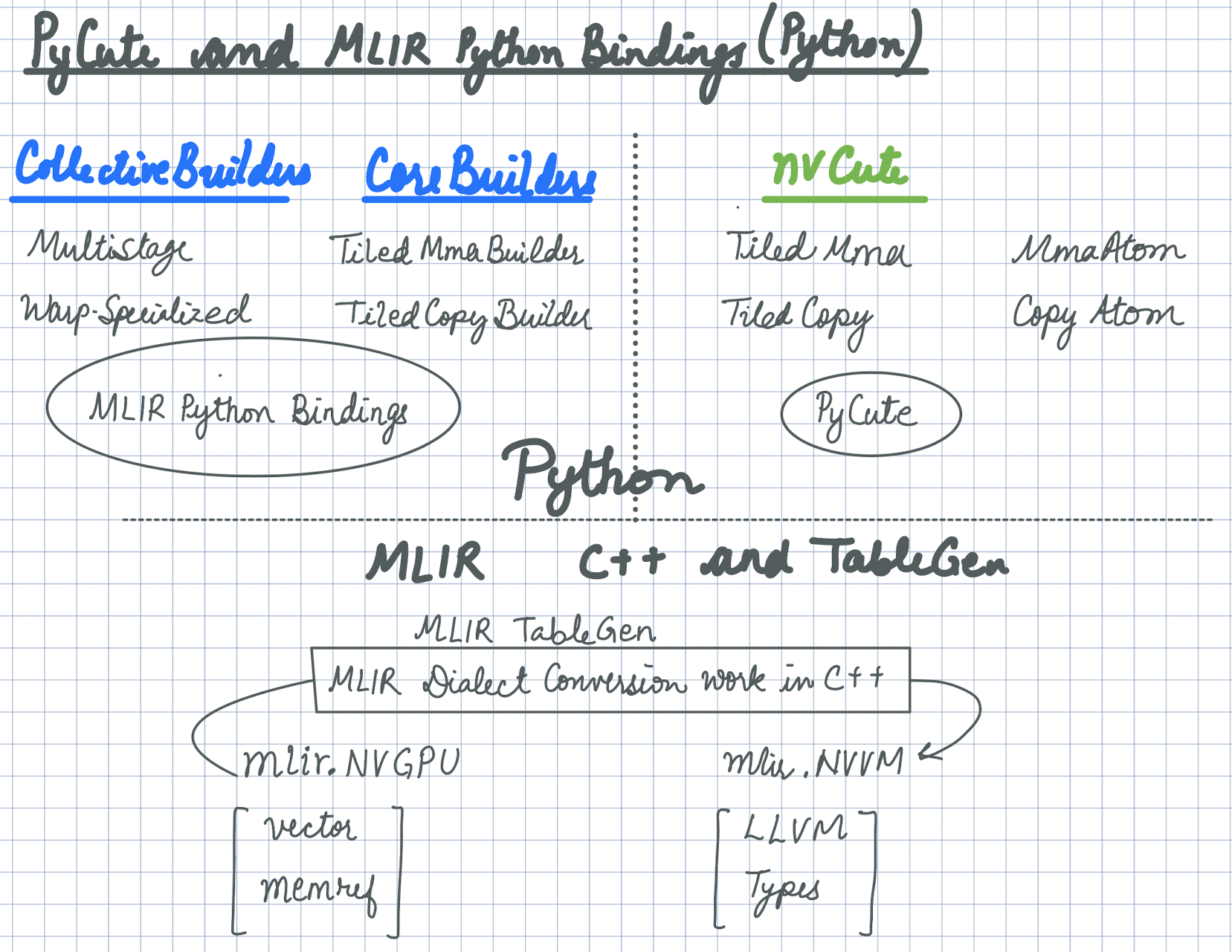

Figure 2. Code components building a Hopper codegen solution "almost" all in Python.-

pycute is used from third-party/cutlass/python/pycute to handle Layout and Layout algebra e.g.

layout_composition,logical_divide,zipped_divide,layout_productetc. Note that the four Python files in the cutlass/python/pycute folder is all that his project depends on from the NVIDIA/CUTLASS repo. Isn't it amazing that these four files are so powerful that it can handle multiple generation of NVIDIA architectures and more! -

nvcute built in this repo on top of

pycuteto handle NVIDIA architecture-specific details soley in Python. This part doesn't use any MLIR (Python bindings or C++).- MmaAtom encodes the details of

wgmmaTensor Core instructions such as instruction shape, operand, and accumulator layout. - TiledMma Tiles

MmaAtomon a CTA tile.- Computes the number

MmaAtom[s] required to fill the CTA tile m-, n-, and k-dimensions. - Creates desc for A and B operands in shared memory.

- Finds the increments in bytes along m-, n-, and k- dimensions as the

MmaAtomare tiled on a CTA.

- Computes the number

- TiledCopy computes the meta information required to tile TMA copy operations to fill the entire tile.

- Shared memory swizzle.

- Number of boxes required to fill the CTA when using TMA copy.

- Shared memory layout after the

TiledCopyoperations.

- MmaAtom encodes the details of

-

codegen is where we use the meta information from

nvcutecomponents and use it to generate/build kernels using MLIR Python bindings. Note that any component or file with "builder" as a suffix is an NVGPU IR builder emitting MLIR operations. Please see TiledMmaBuilder and TiledCopyBuilder.

There is existing work showcasing MLIR Python bindings targeting mlir.nvgpu and mlir.nvvm can achieve decent performance on selected cases (a) JAX mosaic GPU work (see commits 1, 2) and (b) LLVM/MLIR work on NVDSL. This work adds value by using PyCute to scale several more senario by making the codegen more general. Additionally, apply the software design philosophy similar to CUDA/C++ (CUTLASS/CuTe) in Pythonic codegen (MLIR Python bindings/PyCute).

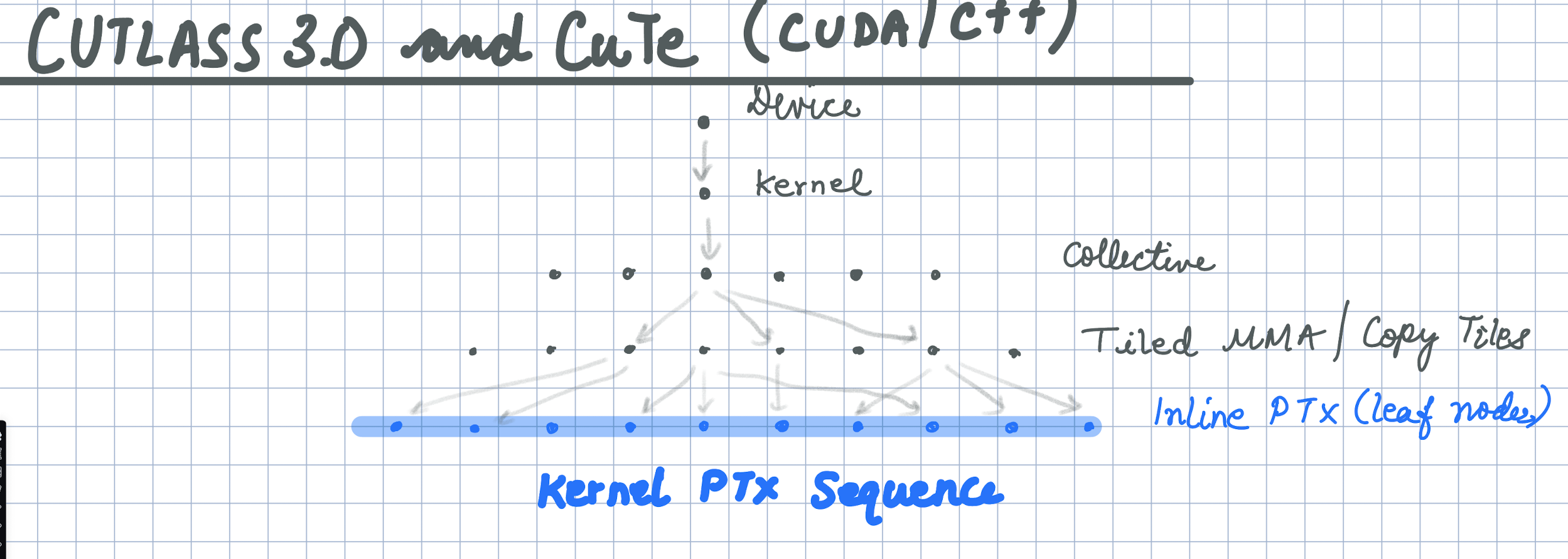

I set out to do this work prove to myself that we can tame the PTX on Hopper architecture and get close to the CUTLASS's PTX using PyCuTe and MLIR Python bindings. If we can get close CUTLASS's PTX in a way we understand it (as much as we can), we should see a similar performance. Refering to Figure 3., I see CUTLASS as codegenerator where C++ compiler triggers a tree of C++ templates to reach leaf nodes of inline PTX stiched together to form a kernel.

Figure 3. Visualization of CUTLASS/CuTe C++ compiler triggering templates to reach inline PTX.From my experience, I am now 98% certain that Hopper codegen is possible all in Python achiving performance and scalability. The remaining 2% is software engineering and design problem, but remember "the last 2% are the hardest part and that's why they leave it in the milk." I am joking here and the remaining work is probably more than 2%, but it is doable.

An MLIR Python-based codegenerator will have some trade-offs which we discuss next. The pros section list the advantanges of using PyCute which are also discussed above.

- PyCute allows us to decoupling address offset computations from the kernel logic and putting it in a reusable components, simplifying the software design part of the problem.

- The use of PyCute and building

Tiled*Buildercomponents that targets specific "Atoms" improves composibility and scalability. For e.g., we may want a kernel with various combinations [cp.async.bulk,wgmma.64mNn16k.descA.descB], [cp.async,wgmma.64mNn16k], [cp.async.bulk,mma.sync.16m8n16k], [cp.async.bulk,ldmatrix,wgmma.64mNn16k.regA.descB]. We createTiled[Mma|Copy]Builderfor each of these components where we change the underlyingMmaAtomorCopyAtomto change emitted PTX sequence. - Improved developer productivity in getting a kernel out of the door, while still having full PTX level control through Python.

- Python-based codegen will be slower than a fully-optimized codegen in C++ in speed of generating the kernel, not the kernel itself. However, the compilation times should be faster than using nvcc on CUDA/C++ templates.

- The solution has a dependence on Python and cannot be shipped as a binary solution.

- To use the full power of CuTe in Python and support layout algebra on runtime values, we need a "

PyCuTeBuilder" that to emitmlir.arithoperations on runtime values. - The approach is more performant as a ahead-of-time compilation strategy. If Python is in the critical path it will slow down just-in-time compilation.

- CUTLASS/CuTe C++ is more powerful than what we intent to build out here as the C++ versions support GETT and contractions on multi-dimensional tensors.

"If we have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants." I express my gratitude to those whose groundbreaking work has paved the way for this study. My thanks go to the colleagues with whom I've had technical interactions and shared experience of working together. Pradeep Ramani, Haicheng Wu, Andrew Kerr, Vijay Thakker, and Cris Cecka working on CUTLASS/CuTe. Guray Ozen and Thomas Raoux on NVGPU and NVVM. Adam Paszke on JAX Moasic GPU. Quentin Colombet, Jacques Pienaar, Aart Bik, Alex Zinenko, and Mehdi Amini on MLIR.