EIP-3005: Batched meta transactions (+ gas usage tests and more)

Simple Summary

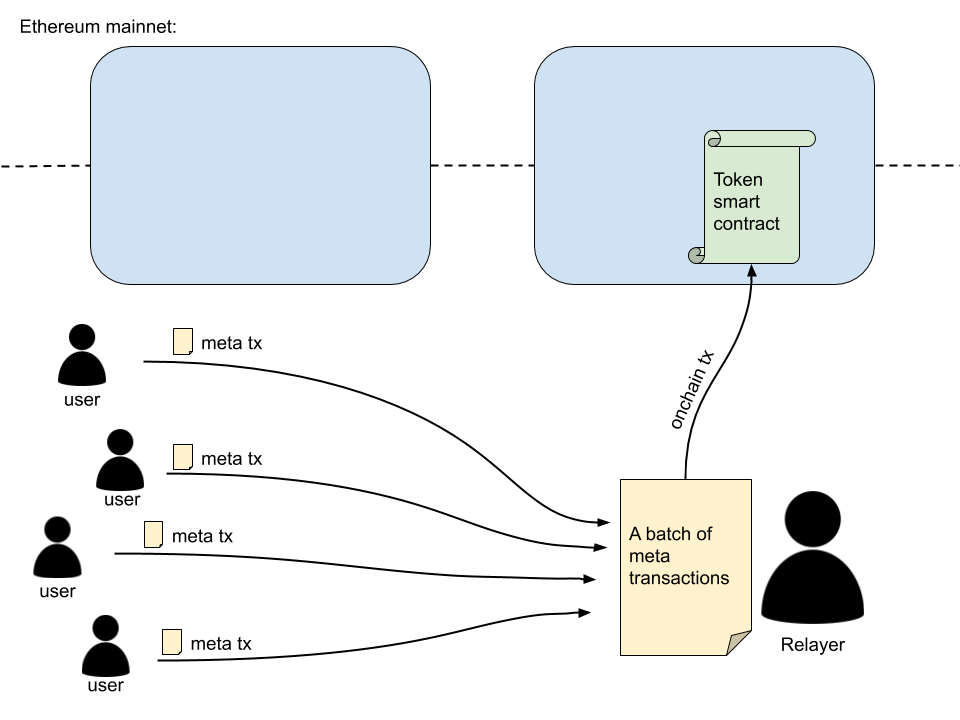

A meta transaction is a cryptographically signed message that a user sends to a relayer who then makes an on-chain transaction based on the meta transaction data. A relayer effectively pays gas fees in Ether, while a meta tx sender can compensate the relayer in tokens (a "gas-less" transaction).

This proposal offers a solution to relay multiple meta transactions as a batch in one on-chain transaction. This reduces the gas cost that the relayer needs to pay, which in turn reduces the relayer fee that each meta tx sender pays in tokens.

Abstract

The current meta transaction implementations (such as Gas Station Network - EIP-1613) only relay one meta transaction through one on-chain transaction (1-to-1: 1 sender, 1 receiver). Gnosis Safe does the same, but can also relay a batch of meta transactions coming from the same sender (a 1-to-M batch: 1 sender, many receivers).

This EIP proposes a new function called processMetaBatch() (an extension to the ERC-20 token standard) that is able to process a batch of meta transactions arriving from many senders to one or many receivers (M-to-M or M-to-1) in one on-chain transaction.

Motivation

Meta transactions have proven useful as a solution for Ethereum accounts that don't have any ether, but hold ERC-20 tokens and would like to move them (gas-less transactions).

The current meta transaction relayer implementations only allow relaying one meta transaction at a time.

The motivation behind this EIP is to find a way to allow relaying multiple meta transactions (a batch) in one on-chain transaction, which also reduces the total gas cost that a relayer needs to cover.

Specification

How the system works

A user sends a meta transaction to a relayer (through relayer's web app, for example). The relayer waits for multiple meta txs to arrive until the meta tx fees (paid in tokens) cover the cost of the on-chain gas fee (plus some margin that the relayer wants to earn).

Then the relayer relays a batch of meta transactions using one on-chain transaction to the token contract (triggering the processMetaBatch() function).

Technically, the implementation means adding a couple of functions to the existing ERC-20 token standard:

processMetaBatch()nonceOf()

You can see the proof-of-concept implementation in this file: ERC20MetaBatch.sol. This is an extended ERC-20 contract with added meta tx batch transfer capabilities (see function processMetaBatch()).

processMetaBatch()

The processMetaBatch() function is responsible for receiving and processing a batch of meta transactions that change token balances.

function processMetaBatch(address[] memory senders,

address[] memory recipients,

uint256[] memory amounts,

uint256[] memory relayerFees,

uint256[] memory blocks,

uint8[] memory sigV,

bytes32[] memory sigR,

bytes32[] memory sigS) public returns (bool) {

address sender;

uint256 newNonce;

uint256 relayerFeesSum = 0;

bytes32 msgHash;

uint256 i;

// loop through all meta txs

for (i = 0; i < senders.length; i++) {

sender = senders[i];

newNonce = _metaNonces[sender] + 1;

if(sender == address(0) || recipients[i] == address(0)) {

continue; // sender or recipient is 0x0 address, skip this meta tx

}

// the meta tx should be processed until (including) the specified block number, otherwise it is invalid

if(block.number > blocks[i]) {

continue; // if current block number is bigger than the requested number, skip this meta tx

}

// check if meta tx sender's balance is big enough

if(_balances[sender] < (amounts[i] + relayerFees[i])) {

continue; // if sender's balance is less than the amount and the relayer fee, skip this meta tx

}

// check if the signature is valid

msgHash = keccak256(abi.encode(sender, recipients[i], amounts[i], relayerFees[i], newNonce, blocks[i], address(this), msg.sender));

if(sender != ecrecover(keccak256(abi.encodePacked("\x19Ethereum Signed Message:\n32", msgHash)), sigV[i], sigR[i], sigS[i])) {

continue; // if sig is not valid, skip to the next meta tx

}

// set a new nonce for the sender

_metaNonces[sender] = newNonce;

// transfer tokens

_balances[sender] -= (amounts[i] + relayerFees[i]);

_balances[recipients[i]] += amounts[i];

relayerFeesSum += relayerFees[i];

}

// give the relayer the sum of all relayer fees

_balances[msg.sender] += relayerFeesSum;

return true;

}Note that the OpenZeppelin ERC-20 implementation was used here. Some other implementation may have named the balances mapping differently, which would require minor changes in the

processMetaBatch()function.

nonceOf()

Nonces are needed due to the replay protection (see Replay attacks under Security Considerations).

mapping (address => uint256) private _metaNonces;

// ...

function nonceOf(address account) public view returns (uint256) {

return _metaNonces[account];

}The EIP-2612 (

permit()function) also requires a nonce mapping. At this point, I'm not sure yet if this mapping should be re-used in case a smart contract implements both EIP-3005 and EIP-2612.At the first glance, it seems the nonce mapping could be re-used, but this should be thought through (and tested) for possible security implications.

What data is needed in a meta transaction?

- sender address (a user that is sending the meta tx)

- receiver address

- token amount to be transferred - uint256

- relayer fee (in tokens) - uint256

- nonce (replay protection within the token contract)

- block number - uint256 (a block by which the meta tx must be processed)

- token contract address (replay protection across different token contracts)

- the relayer address (front-running protection)

- signature (comes in three parts and it signs a hash of the values above):

- sigV - uint8

- sigR - bytes32

- sigS - bytes32

(The bolded data are not sent as parameters, but are still needed to construct a signed hash.)

The front-end implementation (relayer-side)

The processMetaBatch() function is agnostic to how relayers work and are organized.

The function can be used by a network of relayers who coordinate to avoid collisions (meta txs with the same nonce meant for the same token contract). Having a network of relayers makes sense for tokens with lots of traffic.

A relayer would most likely have a website (web3 application) through which a user could submit a meta transaction. Pending meta transactions can be logged in that website's database (and communicated with other relayers to avoid collisions) until the relayer decides to make an on-chain transaction.

Rationale

All-in-one

Alternative implementations (like GSN) use multiple smart contracts to enable meta transactions, although this increases gas usage. This implementation (EIP-3005) intentionally keeps everything within one function which reduces complexity and gas cost.

The processMetaBatch() function thus does the job of receiving a batch of meta transactions, validating them, and then transferring tokens from one address to another.

Function parameters

As you can see, the processMetaBatch() function takes the following parameters:

- an array of sender addresses (meta txs senders, not relayers)

- an array of receiver addresses

- an array of amounts

- an array of relayer fees (relayer is

msg.sender) - an array of block numbers (a due "date" for meta tx to be processed)

- Three arrays that represent parts of a signature (v, r, s)

Each item in these arrays represents data of one meta tx. That's why the correct order in the arrays is very important.

If a relayer gets the order wrong, the processMetaBatch() function would notice that (when validating a signature), because the hash of the meta tx values would not match the signed hash. A meta transaction with an invalid signature is skipped.

Why is nonce not one of the parameters?

Meta nonce is used for constructing a signed hash (see the msgHash line where a keccak256 hash is constructed - you'll find a nonce there). Since a new nonce has to always be bigger than the previous one by exactly 1, there's no need to include it as a parameter array in the processMetaBatch() function, because its value can be deduced.

This also helps avoid the "Stack too deep" error.

Token transfers

Token transfers could alternatively be done by calling the _transfer() function (part of the OpenZeppelin ERC-20 implementation), but it would increase the gas usage and it would also revert the whole batch if some meta tx was invalid (the current implementation just skips it).

Another gas usage optimization is to assign total relayer fees to the relayer at the end of the function, and not with every token transfer inside the for loop (thus avoiding multiple SSTORE calls that cost 5'000 gas).

Backwards Compatibility

The code implementation of batched meta transactions is backwards compatible with ERC-20 (it only extends it with one function).

Security Considerations

Here is a list of potential security issues and how are they addressed in this implementation.

Forging a meta transaction

The solution against a relayer forging a meta transaction is for a user to sign the meta transaction with their private key.

The processMetaBatch() function then verifies the signature using ecrecover().

Replay attacks

The processMetaBatch() function is secure against two types of a replay attack:

Using the same meta tx twice in the same token smart contract

A nonce prevents a replay attack where a relayer would send the same meta tx more than once.

Using the same meta tx twice in different token smart contracts

A token smart contract address must be added into the signed hash (of a meta tx).

This address does not need to be sent as a parameter into the processMetaBatch() function. Instead the function uses address(this) when constructing a hash in order to verify the signature. This way a meta tx not intended for the token smart contract would be rejected (skipped).

Signature validation

Signing a meta transaction and validating the signature is crucial for this whole scheme to work.

The processMetaBatch() function validates a meta tx signature, and if it's invalid, the meta tx is skipped (but the whole on-chain transaction is not reverted).

msgHash = keccak256(abi.encode(sender, recipients[i], amounts[i], relayerFees[i], newNonce, blocks[i], address(this), msg.sender));

if(sender != ecrecover(keccak256(abi.encodePacked("\x19Ethereum Signed Message:\n32", msgHash)), sigV[i], sigR[i], sigS[i])) {

continue; // if sig is not valid, skip to the next meta tx

}Why not reverting the whole on-chain transaction? Because there could be only one problematic meta tx, and the others should not be dropped just because of one rotten apple.

That said, it is expected of relayers to validate meta txs in advance before relaying them. That's why relayers are not entitled to a relayer fee for an invalid meta tx.

Malicious relayer forcing a user into over-spending

A malicious relayer could delay sending some user's meta transaction until the user would decide to make the token transaction on-chain.

After that, the relayer would relay the delayed meta tx which would mean that the user would have made two token transactions (over-spending).

Solution: Each meta transaction should have an "expiry date". This is defined in a form of a block number by which the meta transaction must be relayed on-chain.

function processMetaBatch(...

uint256[] memory blocks,

...) public returns (bool) {

//...

// loop through all meta txs

for (i = 0; i < senders.length; i++) {

// the meta tx should be processed until (including) the specified block number, otherwise it is invalid

if(block.number > blocks[i]) {

continue; // if current block number is bigger than the requested number, skip this meta tx

}

//...Front-running attack

A malicious relayer could scout the Ethereum mempool to steal meta transactions and front-run the original relayer.

Solution: The protection that processMetaBatch() function uses is that it requires the meta tx sender to add the relayer's Ethereum address as one of the values in the hash (which is then signed).

When the processMetaBatch() function generates a hash it includes the msg.sender address in it:

msgHash = keccak256(abi.encode(sender, recipients[i], amounts[i], relayerFees[i], newNonce, blocks[i], address(this), msg.sender));

if(sender != ecrecover(keccak256(abi.encodePacked("\x19Ethereum Signed Message:\n32", msgHash)), sigV[i], sigR[i], sigS[i])) {

continue; // if sig is not valid, skip to the next meta tx

}If the meta tx was "stolen", the signature check would fail because the msg.sender address would not be the same as the intended relayer's address.

A malicious (or too impatient) user sending a meta tx with the same nonce through multiple relayers at once

A user that is either malicious or just impatient could submit a meta tx with the same nonce (for the same token contract) to various relayers. Only one of them would get the relayer fee (the first one on-chain), while the others would get an invalid meta transaction.

Solution: Relayers could share a list of their pending meta txs between each other (sort of an info mempool).

The relayers don't have to fear that someone would steal their respective pending transactions, due to the front-running protection (see above).

If relayers see meta transactions from a certain sender address that have the same nonce and are supposed to be relayed to the same token smart contract, they can decide that only the first registered meta tx goes through and others are dropped (or in case meta txs were registered at the same time, the remaining meta tx could be randomly picked).

At a minimum, relayers need to share this meta tx data (in order to detect meta tx collision):

- sender address

- token address

- nonce

Too big due block number

The relayer could trick the meta tx sender into adding too big due block number - this means a block by which the meta tx must be processed. The block number could be far in the future, for example, 10 years in the future. This means that the relayer would have 10 years to submit the meta transaction.

One way to solve this problem is by adding an upper bound constraint for a block number within the smart contract. For example, we could say that the specified due block number must not be bigger than 100'000 blocks from the current one (this is around 17 days in the future if we assume 15 seconds block time).

// the meta tx should be processed until (including) the specified block number, otherwise it is invalid

if(block.number > blocks[i] || blocks[i] > (block.number + 100000)) {

// If current block number is bigger than the requested due block number, skip this meta tx.

// Also skip if the due block number is too big (bigger than 100'000 blocks in the future).

continue;

}This addition could open new security implications, that's why it is left out of this proof-of-concept. But anyone who wishes to implement it should know about this potential constraint, too.

The other way is to keep the processMetaBatch() function as it is and rather check for the too big due block number on the relayer level. In this case, the user could be notified about the problem and could issue a new meta tx with another relayer that would have a much lower block parameter (and the same nonce).

Other considerations

How much is the relayer fee?

The meta tx sender defines how big the fee they want to pay to the relayer.

Although it is more likely that the relayer will suggest (maybe even enforce) a certain amount of the relayer fee via the UI (the web3 application).

How can relayer prevent an invalid meta tx to be relayed?

The relayer can do some meta tx checks in advance before sending it on-chain.

- Check if a signature is valid

- Check if a sender or a receiver is a null address (0x0)

- Check if a sender and a receiver are the same address

- Check if some meta tx data is missing

Does this approach need a new type of a token contract standard, or is it a basic ERC-20 enough?

This approach would need an extended ERC-20 token standard (we could call it ERC20MetaBatch).

This means adding a couple of new functions to ERC-20 that would allow relayers to transfer tokens for users under the condition the meta tx signatures (made by original senders) are valid. This way meta tx senders don't need to trust relayers.

Is it possible to somehow use the existing ERC-20 token contracts?

This might be possible if all relayers make the on-chain transactions via a special "relayer smart contract" (which then sends multiple txs to token smart contracts).

But this relayer smart contract would need to have a token spending approval from every user (for each token separately), which would need to be made on-chain, or via the permit() function.

More info here:

- https://github.com/defifuture/relayer-smart-contract

- https://github.com/defifuture/M-to-1-relayer-smart-contract

Types of batched meta transactions

There are three main types of batched meta transactions:

- 1-to-M: 1 sender, many recipients

- M-to-1: many senders, 1 recipient

- M-to-M: many senders, many recipients

Right from the start, we can see that 1-to-M use case does not make sense for this implementation, because if there's only one unique sender in the whole batch, there's no need to sign and then validate each meta tx separately (which costs additional gas). In this case, a token multisender such as Disperse.app can be more useful (higher throughput) and less costly.

The Gas usage section below will thus focus only on the M-to-1 and M-to-M use cases.

There are two additional types of batched meta transactions:

- A batch where sender and recipient are the same address

- A batch that has only one unique sender and only one unique recipient (but both different from each other)

Both of these examples are very impractical and are not useful in reality. But the gas usage tests for both were made anyway (Test #2 and #3, respectively) and can be found in the calculateGasCosts.js file in the test folder.

Gas usage tests

Gas usage is heavily dependent on whether a meta transaction is the first transaction of a sender (where prior nonce value is zero) and whether the receiver held any prior token balance.

The gas usage tests are thus separated into two groups:

- First-meta-transaction tests (initially sender has a zero nonce, and a receiver has a zero token balance)

- Second-meta-transaction tests (sender has a non-zero nonce value, and a receiver has a non-zero token balance)

All the tests were run with different batch sizes:

- 1 meta tx in the batch

- 5 meta txs in the batch

- 10 meta txs in the batch

- 50 meta txs in the batch

- 100 meta txs in the batch

Benchmarks

There are two types of benchmarks that ERC-3005 can compare with in regards of gas usage.

1) On-chain token transactions (36'000 or 51'000 gas)

One benchmark type is a normal on-chain token transfer transaction.

There are two possible benchmarks here and they both depend on whether a recipient has a prior non-zero token balance, or not.

In case a recipient's token balance (prior to the meta tx) is zero, the on-chain transaction cost is 51'000 gas.

But if a recipient's token balance is bigger than zero, the on-chain token transfer transaction would cost only 36'000 gas.

2) Other meta tx relaying services (144'315 - 191'650 gas)

Another type of a benchmark are other meta tx services like Gas Station Network (GSN).

GSN gas usage for a relayer sits between 144'315 and 191'650 gas (per meta tx), based on transactions made on Kovan testnet (source 1, source 2).

Benchmark results

The first meta transaction

In this group of tests, a sender's nonce prior to the meta tx is always 0.

M-to-1 (to a zero-balance receiver)

The M-to-1 (many senders, 1 receiver with a zero token balance) gas usage test results are the following:

- 1 meta tx in the batch: 88666/meta tx (total gas: 88666)

- 5 meta txs in the batch: 47673.6/meta tx (total gas: 238368)

- 10 meta txs in the batch: 42553/meta tx (total gas: 425530)

- 50 meta txs in the batch: 38485.5/meta tx (total gas: 1924275)

- 100 meta txs in the batch: 38025.83/meta tx (total gas: 3802583)

A further test has been done to determine that having 4 meta txs in a batch costs 50232 gas/meta tx.

Note that in this case the "On-chain token transfer" benchmark should be closer to 36'000, because only the first tx in the batch is sent to the receiver with a 0 balance. After that, receiver does not have a 0 balance anymore.

Benchmarks score:

- On-chain token transfer:

❌ - Gas station network:

✅

M-to-1 (to a non-zero balance receiver)

The M-to-1 (many senders, 1 receiver with a non-zero token balance) gas usage test results are the following:

- 1 meta tx in the batch: 73666/meta tx (total gas: 73666)

- 5 meta txs in the batch: 44671.2/meta tx (total gas: 223356)

- 10 meta txs in the batch: 41049.4/meta tx (total gas: 410494)

- 50 meta txs in the batch: 38182.62/meta tx (total gas: 1909131)

- 100 meta txs in the batch: 37875.83/meta tx (total gas: 3787583)

Benchmarks score:

- On-chain token transfer:

❌ - Gas station network:

✅

M-to-M (to a zero-balance receiver)

The M-to-M (many senders, many receivers) gas usage test results are the following:

- 1 meta tx in the batch: 88666/meta tx (total gas: 88666)

- 5 meta txs in the batch: 63031.2/meta tx (total gas: 315156)

- 10 meta txs in the batch: 59833/meta tx (total gas: 598330)

- 50 meta txs in the batch: 57298.86/meta tx (total gas: 2864943)

- 100 meta txs in the batch: 57032.51/meta tx (total gas: 5703251)

Benchmarks score:

- On-chain token transfer:

❌ - Gas station network:

✅

M-to-M (to a non-zero balance receiver)

In this example (as opposed to the previous one), the recipient has a prior non-zero token balance:

- 1 meta tx in the batch: 73678/meta tx (total gas: 73678)

- 5 meta txs in the batch: 48038.4/meta tx (total gas: 240192)

- 10 meta txs in the batch: 44842.6/meta tx (total gas: 448426)

- 50 meta txs in the batch: 42310.62/meta tx (total gas: 2115531)

- 100 meta txs in the batch: 42032.75/meta tx (total gas: 4203275)

Benchmarks score:

- On-chain token transfer:

❌ - Gas station network:

✅

The second meta transaction (and subsequent transactions)

Note that in this group of tests, the sender's nonce is a non-zero value (more precisely: 1). This brings visible gas reductions.

M-to-1 (to a non-zero balance receiver)

- 1 meta tx in the batch: 58666/meta tx (total gas: 58666)

- 5 meta txs in the batch: 29671.2/meta tx (total gas: 148356)

- 10 meta txs in the batch: 26048.2/meta tx (total gas: 260482)

- 50 meta txs in the batch: 23183.1/meta tx (total gas: 1159155)

- 100 meta txs in the batch: 22876.07/meta tx (total gas: 2287607)

An additional test showed that the "On-chain token transfer" benchmark (36'000) is beaten already at 3 meta transactions in a batch.

Benchmarks score:

- On-chain token transfer:

✅ - Gas station network:

✅

M-to-M (to a zero-balance receiver)

- 1 meta tx in the batch: 73666/meta tx (total gas: 73666)

- 5 meta txs in the batch: 48026.4/meta tx (total gas: 240132)

- 10 meta txs in the batch: 44829.4/meta tx (total gas: 448294)

- 50 meta txs in the batch: 42298.14/meta tx (total gas: 2114907)

- 100 meta txs in the batch: 42032.27/meta tx (total gas: 4203227)

In this case, the "On-chain token transfer" benchmark is 51'000, because the receiver has a zero-value balance. This M-to-M example beats the benchmark starting from 4 meta txs in a batch.

Benchmarks score:

- On-chain token transfer:

✅ - Gas station network:

✅

M-to-M (to a non-zero balance receiver)

- 1 meta tx in the batch: 58666/meta tx (total gas: 58666)

- 5 meta txs in the batch: 33024/meta tx (total gas: 165120)

- 10 meta txs in the batch: 29830.6/meta tx (total gas: 298306)

- 50 meta txs in the batch: 27307.98/meta tx (total gas: 1365399)

- 100 meta txs in the batch: 27033.59/meta tx (total gas: 2703359)

An additional test shows that 4 or more meta txs in a batch have a lower average gas than the "On-chain token transfer" benchmark (36'000).

Benchmarks score:

- On-chain token transfer:

✅ - Gas station network:

✅

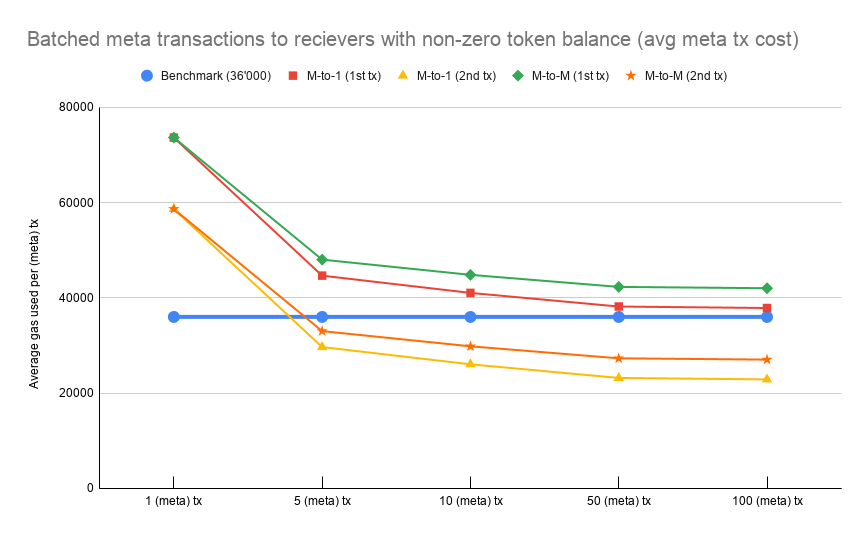

Comparing ERC-3005 gas cost to on-chain token transfer gas cost

Graph

This graph represents how M-to-1 and M-to-M fare in the case of the first and the second sender's meta transactions - compared to on-chain token transfer cost.

Note that only transactions where the benchmark is 36'000 are included (meaning the recipient has a prior non-zero token balance).

The economics of ERC-3005 vs on-chain token transfers

Let's consider the real-world economic viability of both use cases, M-to-M and M-to-1, by calculating gas cost in USD for each.

First, we need to make a few assumptions:

A) The gas price is 500 Gwei

The purpose of batched meta transactions is to lower the tx cost for the end-user, which means batching comes useful in times of high gas prices.

B) Ether price is 350 USD

At the time of writing these words, the ETH price is 350 USD, so let's take this as the price for our transaction cost calculations.

C) All meta transactions are sent to receivers with non-zero token balances

This means the benchmark is always 36'000 gas. Having a constant benchmark will make calculations and cost comparisons easier.

D) A relayer sends the batch after it reaches the size of 50 meta txs

Let's say the token is very popular, so there are plenty of people who want to send a meta transaction and the relayer has no trouble getting 50 meta transactions into a single batch.

E) A relayer includes (in a batch) no more than 15 meta txs from first-time senders

Meta transactions coming from first-time senders are the most expensive (because these senders have a zero nonce value).

Since meta txs from first-time senders do not go below the benchmark, the relayer subsidizes them by charging second-time senders more.

F) The relayer wants to earn a margin equivalent to 1000 gas per each meta transaction

Running a relayer is a business that needs to earn a margin (and make a profit) in order to make it viable.

Following the above assumptions, the formula to calculate the gas cost in USD is:

gas cost in USD = 0.000000001 * 500 Gwei * 350 USD * gas amount

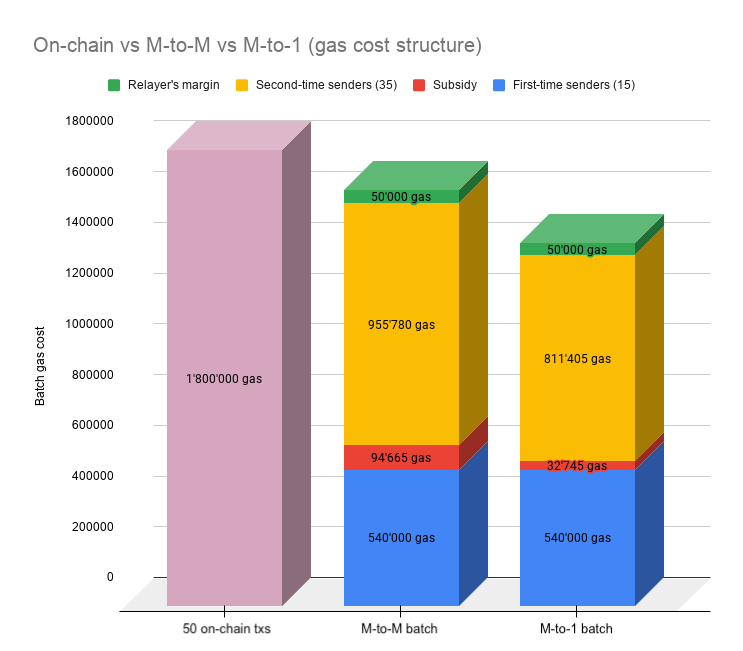

M-to-M example

As per our assumptions, there are 15 first-time senders. The cost of each such meta tx is 42'310.62 gas/mtx. This is obviously above the benchmark:

gas amount above benchmark = (42311 gas/mtx - 36000) * 15 = 94665 gas

The gas amount above the benchmark for all 15 first-time senders is 94'665 gas.

With the second-time senders, the story is just the opposite. Each of their meta transactions costs 27'307.98 gas/mtx, which is well below the benchmark.

gas amount below benchmark = (36000 - 27308 gas/mtx) * 35 = 304220 gas

The gas savings for all the 35 second-time senders is 304'220 gas.

Since relayers are passing the gas cost overages (over the benchmark) of first-time senders to second-time senders, we need to make additional calculations in order to determine the final gas cost per meta tx for second-time senders.

We need to subtract the gas cost overage of first-time senders from the gas savings of second-time senders. In addition, we also need to subtract the margin that the relayer expects from this batch (50 * 1000 gas):

final gas savings for second-time senders = 304220 - 94665 - 50000 = 159555 gas

Next, let's divide this number by the amount of second-time senders:

final gas savings per each second-time sender = 159555 / 35 = 4559 gas

Instead of saving around 8'700 gas per meta tx, each second-time sender will only save 4'559 gas (due to subsidizing first-time senders).

The meta tx gas cost for second-time senders is now the following:

meta tx gas cost = 36000 - 4559 = 31441 gas

To sum up, let's take a look at how much each of the users would pay for a meta transaction (or earn in case of a relayer):

- First-time sender: 6.30 USD/mtx (0 USD savings compared to benchmark)

- Second-time sender: 5.50 USD/mtx (0.80 USD/mtx savings compared to benchmark)

- Relayer's margin: 0.175 USD/mtx (8.75 USD for the whole batch)

The second-time sender would pay 13% less in tx fees by submitting a meta tx, compared to doing an on-chain token transfer transaction (benchmark).

M-to-1 example

Again, there are 15 first-time senders, whose meta transactions cost 38182.62 gas/mtx each. This is slightly above the benchmark:

gas amount above benchmark = (38183 gas/mtx - 36000) * 15 = 32745 gas

The gas amount above the benchmark for all 15 first-time senders is 32'745 gas.

With the second-time senders, the story is the opposite (gas savings instead of gas cost overage). Each meta tx of a second-time sender costs only 23'183.1 gas/mtx:

gas amount below benchmark = (36000 - 23183 gas/mtx) * 35 = 448595 gas

Next, we need to subtract the cost overage of first-time senders and the margin of a relayer:

final gas savings for second-time senders = 448595 - 32745 - 50000 = 365850 gas

Now, let's divide this number by the amount of second-time senders:

final gas savings per each second-time sender = 365850 / 35 = 10453 gas

The meta tx gas cost for second-time senders is the following:

meta tx gas cost = 36000 - 10453 = 25547 gas

This is, of course, less than the original amount of 23'183.1 gas/mtx, but still significantly below the benchmark.

To sum up, let's take a look at how much each of the users would pay for a meta transaction (or earn in case of a relayer):

- First-time sender: 6.30 USD/mtx (0 USD savings compared to benchmark)

- Second-time sender: 4.47 USD/mtx (1.83 USD/mtx savings compared to benchmark)

- Relayer's margin: 0.175 USD/mtx (8.75 USD for the whole batch)

The second-time sender would pay 30% less in tx fees by submitting a meta tx, compared to doing an on-chain token transfer transaction (benchmark).

Graph: batch gas structure comparison

Conclusion

The gas usage tests shows that normal on-chain token transactions can often make more sense than using meta transactions.

Why would someone want to use meta transactions then?

Meta transactions come useful for gas-less transactions, when a user doesn't have any ETH on their account.

In this case, the user might decide to use meta transactions even if it's a bit costlier - although considering that the alternative means buying ETH first and transferring it to an account, (ERC-3005) meta transactions can actually be cheaper in all cases.

Compared to other meta transaction services, EIP-3005 is less gas demanding. But some of these services take advantage of the permit() function, which means they can offer relays of much broader amount of tokens than EIP-3005.

So in the end, it depends on the use case. In some use cases, one way of transferring tokens is more suitable, in other cases some other way.

Nevertheless, the topic of meta transactions should be explored further in order to find the right use cases where meta transactions can provide a valuable solution.

Sources

- Griffith, Austin Thomas (2018): Ethereum Meta Transactions, Medium, 10 August 2018.

- Kharlamov, Artem (2018): Disperse Protocol, GitHub, 27 November 2018.

- Lundfall, Martin (2020): EIP-2612: permit – 712-signed approvals, Ethereum Improvement Proposals, no. 2612, April 2020.

- Sandford, Ronan (2019): ERC-1776 Native Meta Transactions, GitHub, 25 February 2019.

- Weiss, Yoav, Dror Tirosh, Alex Forshtat (2018): EIP-1613: Gas stations network, Ethereum Improvement Proposals, no. 1613, November 2018.

Feedback

I'm looking forward to your feedback!

P.S.: A huge thanks to Patrick McCorry (@stonecoldpat), Artem Kharlamov (@banteg), Matt (@lightclient), and Ronan Sandford (@wighawag) for providing valuable feedback.