- Overview

- To run after installing, go to directory with the

.plfile andswipl likes.pl(where likes.pl is name of file)?- likes(joe,money).to produce boolean answer?- owns(john, book(_, author(_, bronte))).to produce boolean answer if john owns a book by a author with bronte surname.?- owns(john, book(X, author(Y, bronte))).to produce answers for who is the X and who is the Y??- likes(john,X).to produce what john likes.- to quit

- after answer means happy with 1 answer

- To have more answers like uninstantiated variables outcome, hit

; - if before fullstop, next line is | so to complete the query, insert

. - comment out with

/* .... */(see 01.Tutorial_Introduction/sister.pl) and can also be used to number /1/ (see 01.Tutorial_Introduction/steal.pl ) - Enclose capitalised words with '' e.g event(1505,['Euclid',translated, into 'Latin']) so they wont read as variables.

read( X )in goal to create interactive QA program. After swipl file.pl, SOMETHING +.+(enter)to retrieve the accompanying contents e.ghello1(Event) :- read(Date), event(Date, Event).

?- hello1(X). |: 1523. X = ['Christian', 'II', flees, from, 'Denmark']. - Additional material https://www.swi-prolog.org/pldoc/man?section=quickstart

- To run after installing, go to directory with the

- Ch01 Tutorial Introduction

- Rules

- usually oversimplified & accepted as definitions e.g sisters = 2 females with same parents

- Prolog is a storehouse of facts and rules which it uses to answer questions. Prolog requires

- specifying some facts about objects and their relationships

- defining some rules about objects and their relationships

- asking questions about objects and their relationships

- Facts

- relationships + objects in lower case. likes (john, mary). = john likes mary

- 1st r/s then 2nd objects with commas.

- must have full stop

- arbitrary order but must be consistent

- many ways to interpret a name as determined by the programmer.

- names in bracket = arguments vs relationship before bracket = predicate

- e.g valuable (gold). vs likes (john, mary). valuable = predicate with 1 argument vs likes = predicate with 2 arguments.

- Collection of facts (and / rules) = database

- Questions

- with ?- e.g ?- owns(mary, book) = Does Mary own the book?

- unify Answers in Prolog is found by searching through the database for facts that unify the fact in the question , meaning

- predicates are same

- arguments are the same

- then answer = yes

- Variables

- To list all the possibilies e.g whatever John like

Xfor objects yet to be named.- instantiated variable = known object

- uninstantiated variable = unknown object

- Variable start with capital letter

- After a variable is found, we say it is instantiated (here to book)

?- likes(john,X). X = book . - Conjugation

- and

- to ask each other type question , use

,e.g do john and mary like each other:?- likes(john,mary),likes(mary,john).Note. If many conditions, just extend with more,. - to ask common variable object questions like what do mary and john like in common:

?- likes(mary,X),likes(john,X). - Process. started with code line 16 in 01.Tutorial_Introduction/likes.pl

- When a goal is satisfied, Prolog mark the place in database in case there is need to re-satisfy ie instantiated first likes(mary,chocolate). and chocolate is marked everywhere in the database

- Then the second part looks for likes(john,chocolate). in the database but this is not found.

- So Prolog looks for next likes(mary,X). but starting from where it was marked previously ie likes(mary,chocolate). and make X uninstantiated once more so that X may unify with anything. This means uninstantiating all the chocolate

- Now, it tries til it get the next unifying fact likes(mary,wine). Prolog marks wines in case it must re-satisfy what mary likes later.

- Again, Prolog goes trying for the second goal ie likes(john,wine). As it is not re-satisfying the goal as it is an extension from the LHS, it starts from the start of database until the unifying fact is found n goal is satisfied so it marks its place in case there is need to re-satisfy the goal.

- Answer is where both goals have been satisfied. First goal X rest at wine at the database fact likes(mary,wine). and the second goal rest and make a place-marker at the database fact likes(john,wine).

- To find the second item that both john and mary like with

;to re-satisfy both goals starting from the place-markers they rested at previously. - Prolog satisfy goal from left to right, passing each

, - See backtracking in book: forgetting the previous instantiated X that satisfy the first goal bcos it cannot be instantiated / match for the second goal. And re-attempt to re-satisfy the first goal of likes(mary,X).

- to ask each other type question , use

- and

- Rules

- Compact way than a list of facts e.g John likes every one (in the data base) is tedious. Rule form: John likes any object provided it is a person.

- Consistent interpretation. In a rule, if 1 X stands for Fred, then all X = Fred. But at each different rule, a variable can stand for different object.

- A rule is a general statement about objects and their relationships.

:-means if and is to connect head and body bcos a rule consists of a head and a body.- Adding conditions. Compare

likes(John, X) :- likes(X, wine), likes (X, food). gives John likes anyone who likes wine AND food likes(John, X) :- female(X), likes(X, wine). gives John likes a woman who likes wine - Can be more than a tuple. parents(X, Y, Z). means The parents of X are Y (for mother) and Z (for father)

- Can be singular. male(albert).

- So sisters can be written as

sister_of(X,Y) :- female(X), parents(X, M, F), parents(Y, M, F). - conferences each variable refers to the other. As soon as 1 is instantiated, the other becomes instantiated to the same objected. So for 01.Tutorial_Introduction/sister.pl after loading,

?- sister_of(alice,X).in terminal will returnX = edward - Typically, a predicate is defined by a mixture of facts and rules ie clauses for a predicate. So clause is either a fact or a rule. Example the rule

may_stealdepends on clausesthiefandlikes

may_steal(P,T) :- thief(P), likes (P,T)- For example, in the may_steal rule in 01.Tutorial_Introduction/steal.pl, X stands for the object that can steal something. But in the likes rule, X stands for the object that is liked. In order for this program to make sense, Prolog must be able to tell that X can stand for two different things in two different uses of the clauses.

likes(john,X) :- likes(X, wine). may_steal(X,Y) :- thief(X), likes(X,Y).

- Rules

- Ch02 A Closer Look

-

Prolog allows ways to structure data + the order in which attempts are made to satisfy goals.

-

Prolog programs are built from terms. A term is either a constant, a variable, or a structure and term = sequence of characters.

-

4 forms of characters

- Capital letters

- Lower case letters

- Numerals

- Signs and Symbols

-

Terms

- Constants name specific object or specific relationships. 2 kinds:

- atoms:

- names given e.g likes mary john book can_steal wine

?-(for questions) and:-(rules)

- number with e = power of 10 such that -2.67e2 = -2.67 x 10 x 10

- atoms:

- Variables starts with

- capital letters

- or an under sign "" e.g `?- likes(,john). Allow anonymous variables in the same clause to be given different interpretations.

- Structures = a single object consisting of a collection of other objects, called components which are related.

- The related components are grouped together into a single structure for convenience in handling them. A libary card with author name, title, publication date, location etc is an example of structure bcos it contains components e.g author name which further consist of initials and surname.

- Context of structure is given by specifying the structure functor and its components.

- Below example the book structure inside the fact ie as an argument, it is an object, taking part in a relationship. Another structure for author's name to distinguish among 3 Bronte writers to allow for QA using variables where X is instantiated to title and then Y will be instantiated to the first name. Alternatively, QA can be done with anonynmous "_" to get true/false answer if john owns any book by a bronte author.

owns(john, book(wuthering_heights, author(emily, bronte))). ?- owns(john, book(X, author(Y, bronte))). ?- owns(john, book(_, author(_, bronte))). - A predicate (used in facts and rules) is actually the functor of a structure.

- The arguments of a fact or rule are actually the components of a structure.

- Constants name specific object or specific relationships. 2 kinds:

-

Characters may be

- printable : displayable

- non-printable: non displayable e.g new line

-

Operators

- " x + y *z " is

+(x, *(y,z)). - 3 + 4 is

+(3,4)which is a data structure. - left vs right associative. +-*/ are left associative so 8/4/4 = (8/4)/4 and 5+8/2/2 = 5+((8/2)/2)

- " x + y *z " is

-

Unification.

- When X = Y and Y = something , then X is also equal the same thing. X = the structure rides(student,bicycle) by

?- rides(student,bicycle) = X - atoms and integers only equal to themselves.

- 2 structures are equal if

- same functor

- same number of components

- all corresponding components are equal

- X = Y means they refer to the same thing ie they co-refer

equal(X, Y) :- X = Y

- When X = Y and Y = something , then X is also equal the same thing. X = the structure rides(student,bicycle) by

-

Arithmetic

notation meaning X =:=Y X and Y stand for the same number X ==Y X and Y stand for different number X < Y X is less than Y X > Y X is greater than Y X =< Y X is less than or equal to Y X >= Y X is greater than or equal to Y -

isoperator:-

infix

-

right side is an arithmetic expression

-

so if left is unknown, then all the right variables must be known to evaluate.

-

for arithmetic

/* rule for population (pop) density for a country : The population density of country X is Y, if: The population of X is P, and The area of X is A, and Y is calculated by dividing P by A. */ density(X, Y) :- pop(X, P), area(X, A), Y is P / A . -

issupports:notation meaning X + Y the sum of X and Y X - Y the difference of X and Y X * Y the product of X and Y X / Y the quotient of X divided by Y X // Y the integer quotient of X divided by Y X mod Y the remainder of X divided by Y

-

-

Satisfying goals 1. conjunction of goals to be satisfied 2. via the known clauses e.g fact or a rule to reduce the task to that of satisfying a conjugation of subgoals 3. if a gaol is not satisfied, backtracking will be initiated to re-satisfy the goals to find alterative way to satisfy the goals. 4. can self-initate backtracking by

;5. Start with satisfying the left then move to satisfy the right 6. boxes illustration Fig 2.4:- Arrow moves down the page, passing through the boxes.

- Enter a box, a clause is chosen and its position marked.

- If the clause unifies with the goal and the clause is a fact, then the arrow can leave the box.

- Else if the clause unifies with the goal and the clause is a rule, then new boxes are created for the subgoals. The aarow must pass through all these subgoal boxes before leaving the original big box.

7. Backtracking for failure (bcos alternatives have been tried or bcos

;), the arrows retreat back into the boxes that have previously been left in order to re-satisfy the goals. - first uninstantiated all variables previously instantiated while satisfying the goal.

- searches through the database from where the place-marker was put. When it finds another unifying possibility, it marks the place and recontinue from 6 above.

- Further failure leads to further arrow retreats until it comes to another place-marker, while reset previous choices to uninstantiated.

- Prolog searches through the database for a clause after the place marker. A new place marker is recorded if it finds a clause that unifies with the goal. Boxes for subgoals are created and arrows starts moving downwards again. Otherwise arrows continue retreating upwards to find another place marker.

-

Unification.

?- sum(2+3).unifies with factsum(X + Y).: the argument of the sum structure is a structure with + sign as its functor and 2 and 3 as its components so X is instantiated to 2 and Y is instantiated to 3.- Compare with computation using

ispredicate:?- X is 2 + 3. - verbosely, the rule can be written as

add(X, Y, Z) :- Z is X + Y.

- Compare with computation using

-

- Ch03 Using Data Structures

- head is the first element in a list and tail is the remaining elements

|as in([X|Y])instantiated X to the head and Y to the tail.- With 03.Using_Data_Structures/1list.pl, test

|?- p([X|Y]). X = 1, Y = [2, 3] ; X = the, Y = [cat, sat, [on, the, mat]]. ?- p([_,_,_,[_|X]]). X = [the, mat]. ?- p([_,_,_,[A|X]]). A = on, X = [the, mat]. - Recursion case here has 2 boundary conditions -- either existent or not in the list

- First boundary condition is first clause to cause the search through the list to be stopped if the first argument of member matches the head of the second argument.

- Second boundary condition is when the second argument of member is the empty list. ie complete search to the end already.

/* Fact: X as a member of the list that has X as its head */ member(X, [X|_]). /* As a rule alternatively*/ member(X, [Y|_]) :- X = Y. /* recursion : X is a member of the list if X is a member of the tail of the list*/ member(X, [_|Y]) :- member(X,Y). - Be careful about

- ending with "circular definition". chicken and egg problem

parent(X, Y) :- child(Y, X). child(A, B) :- parent (B, A). - Where subgoal relies on another goal which is the subgoal which run until memory runs out.

person(adam). person(X) :- person(Y), mother(X, Y). AND QUESTION IS ?- person(X). SOLUTION is put rule before fact. person(X) :- person(Y), mother(X, Y). person(adam).

- ending with "circular definition". chicken and egg problem

- Try to put rule before fact: see solution to issue 2 above except for when exceptional tail must be empty list case

SOLUTION is put rule before fact. person(X) :- person(Y), mother(X, Y). person(adam). EXCEPTION islist([A|B]) :- islist(B). islist([]).

- Mapping (refer to 03.Using_Data_Structures/2translate.pl)

- definition: traverse the old structure component by component and construct the components of the new structure. ie retain old structure but with some modification.

- in Dialog example (03.Using_Data_Structures/2translate.pl) Change 'do' to 'no', 'french' to 'german', and 'you' to 'I' for "do you speack french?" to return "no i speak german"

- So translation is actually altering a list with head H and tail T gives a list with head X and tail Y if:

- changing word H gives word X, and

- altering the list T gives the list Y.

- Translation involve database of many facts

change(X,Y).and a catchall fact - first clause check for empty list. and also for end of of list as well

- Example

alter([], []). alter([H|T],[X,Y]) :- change(H, X), alter(T, Y). ?- alter([you, are, a, computer], Z). Z = [i, [[am, not], [a, [computer, []]]]] - First step

- H is "you"

- T is [are, a, computer]

- Translate with goal

change(you,X).from the facts in 03.Using_Data_Structures/2translate.pl so X is "i". As X is the head of output list inalter([H|T],[**X**,Y]), the first word in utput list is "i". - Next phase goal alter([are, a, computer], Y) follows the same rule with "are" being translate by

change(are, [am, not]).such thatarebecomes the list[am, not]by the database. - This eventually leaves us with

alter([a, computer], Y).- Searching through the database for

change(a, X)without success leads to the catchall factchange(X, X)so "a" remains "a" - Return to

alterrule again withcomputeras head of input list and[]as tail of input list. change(computer,X)matches with the catchall.- Finally

alteris called with the empty list[]which matches the first alter clausealter([], []).resulting in an empty list thus ending the sentence. (rem a list ends with an empty tail).

- Searching through the database for

- Put together prologs responds with

Z = [i, [[am, not], [a, [computer, []]]]]orZ = [i, [am, not], a, computer]. - Interesting notes:

[am, not]is in the output list. It is essentially an example of a list that is a member of another list.- boundary conditions occurs when

- fact

alter([], []).for when input list becomes empty list , then terminate the output list by putting an empty list at its end, and - catchall

change(X, X).for when all the change facts have been combed through, then retain the word unchanged by changing it into itself.

- fact

- Example

- Recursive Comparison (See 03.Using_Data_Structures/3compare_car.pl)

- First create a predicate fuel_consumed for car with list of fuel consumption over 4 routes in their order.

fuel_consumed(waster, [3.1, 10.4, 15.9, 10.3]). fuel_consumed(guzzler, [3.2, 9.9, 13.0, 11.6]). fuel_consumed(prodigal, [2.8, 9.8, 13.1, 10.4]). - The comparison predicate

equal_or_better_consumptionto compare 2 consumption with underlying yardstick -- consumption is equal or better" if less than 5% more than the ave of the two. So the threshold is 1/20 of the average or 1/40 of the sum.equal_or_better_consumption(Good, Bad) :- Threshold is (Good + Bad) / 40, Worst is Bad + Threshold, Good < Worst. - Rule to compare 2 cars based on their fuel consumption that over each of the 4 routes, it beats the relative car.

prefer(Car1, Car2):- fuel_consumed(Car1, Con1), fuel_consumed(Car2, Con2), always_better(Con1, Con2). - A rule to compare consumption for 2 cars across each corresponding element across the list of 4 routes.

- Code rules

always_better([], []). always_better([Con1|T1], [Con2|T2]) :- equal_or_better_consumption(Con1, Con2), always_better(T1, T2). always_better([Con1|T1], [Con2|T2])means first list is always better if its headCon1is equal or better consumption that the comparative headCon2and plus its tail of first listT1is always better than the tail of the comparative listT2.- Above is recursion: Test heads of 2 lists, then the 2 heads via second layer/element of remaining lists, then 3rd pair of heads of the original lists which is the remaining lists of last 2 routes. This continues until all 4 corresponding elements in 2 respective lists are compared, each time invoking recursion.

- When the boundary condition fails ie

equal_or_better_consumptionfails, the originalalways_bettergoal will fail also.

- Code rules

- Subtly different from

always_betterissometimes_better.sometimes_betterachieve boundary condition when an element in first list is a better consumption than corresponding element in the second list. ie succeed without going any further down the list. Note that at least 1 pair of elements needs to be better otherwise the predicate would fail bcos both both clauses specify non-empty lists in both arguments.sometimes_better([Con1|_],[Con2|_]) :- equal_or_better_consumption(Con1, Con2). sometimes_better([_|Con1], [_|Con2]) :- sometimes_better(Con1, Con2). - Ex 3.1 A significant better consumption comparison. See 03.Using_Data_Structures/3compare_car.pl :

significant_better_consumption(Good, Bad) :- Good < Bad , Margin is (abs(Bad - Good)) * 2, Good < (4 * Margin). significant_better([Con1|_],[Con2|_]) :- significant_better_consumption(Con1, Con2). significant_better([_|Con1], [_|Con2]) :- significant_better(Con1, Con2).- Test with

?- significant_better_consumption(4,5). true. ?- significant_better_consumption(4.8,5). false. ?- significant_better_consumption(2,10). true. - Within expectation

/* bcos 2nd head is true */ ?- significant_better([4.8,1,4.5] ,[5,5,5]). true /* bcos 1st head is true */ ?- significant_better([1 ,4.8, 4.5 ], [5 ,5, 5 ]). true /* bcos none is true */ ?- significant_better([5 ,4.8, 4.5 ], [5 ,5, 5 ]). false.

- Test with

- First create a predicate fuel_consumed for car with list of fuel consumption over 4 routes in their order.

- Joining Structures Together

- Definition of

append2 lists into 1 list:append([], L, L). append([X|L1], L2, [X|L3]) :- append(L1, L2, L3). /* returns */ ?- append([alpha, beta], [gamma, delta], X). X = [alpha, beta, gamma, delta]. ?- append(X, [b, c, d], [a,b,c,d]). X = [a]- Boundary condition is when first list is empty list. Then what returns is the appended list.

- Second rule has 3 principles:

- Head of first list ie

Xwill become the head of the 3rd list. - Second argument

L2will append to tail of first list (L1) to form/become tail of the 3rd argumentL3. - Pt 2 is perform via the recursive append.

- Continually take head of remaining tail from first argument until it becomes empty list ie until the boundary condition

append([], L, L).occurs.

- Head of first list ie

- Like the bicycle parts in 03.Using_Data_Structures/5bicycle.pl and hierachical tree, partsoflist can be applied to generate sentences from a grammar after decomposition into noun phrase, verb phrase, determiner.

- Definition of

- Accumulator

- Len of list without accumulator:

listlen([],0). listlen([H|T], N) :- listlen(T, N1), N is N1 + 1.- 2 clauses: the boundary condition and the recursive case

- Boundary condition = empty list has length 0.

- Recursive case with rule that the length of non-empty list is computed by adding 1 to length of the tail of the list.

- With accumulator

/* format */ lenacc(L, A, N). listlen(L, N) :- lenacc(L, 0, N). lenacc([], A, A). lenacc([H|T], A, N) :- A1 is A + 1, lenacc(T, A1, N).lenacc([], A, A).For empty list, the length is whatever has been accumulated so far (A).- Second clause

A1 is A + 1increase accumulation by 1 to becomeA1. Then recur on the tail withA1. - Sequence for list [a, b, c, d, e]:

- lenacc([a, b, c, d, e], 0, N)

- lenacc([b, c, d, e], 1, N)

- lenacc([c, d, e], 2, N)

- lenacc([d, e], 3, N)

- lenacc([ e], 4, N)

- lenacc([], 5, N)

- activate boundary condition lenacc([], A, A).

- N becomes instantiated to 5 as N = A as A = 5.

- Bicycle parts with accumulator 03.Using_Data_Structures/7accum_bicycle.pl vs 5bicycle.pl

partsacc/* NEW */ /* with accumulator */ partsof(X, P) :- partsacc(X, [], P). partsacc(X, A, [X|A]) :- basicpart(X). /* partsacc is similar to 5bicycle.pl partsof except for accumulator partsacc (X, A, P) means the parts of object X, when added to the list A, gives the list P. */ partsacc(X, A, P) :- assembly(X, Subparts), partsacclist(Subparts, A, P).- first clause of

partsacc(X, A, [X|A]) :- basicpart(X).construct a new list with head being the first argumentXand tail being the accum list of parts. Condition is object is a basic part. - second clause of

partsacc(X, A, P) :- assembly(X, Subparts), partsacclist(Subparts, A, P).is applicable for objects which are assembly. 1st find the list of subparts, then applypartsacclistto find subparts of each part in the list

- first clause of

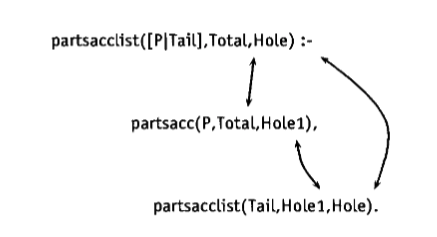

partsacclist/* partsacclist is similar to 5bicycle.pl partsoflist except for accumulator*/ partsacclist([], A, A). partsacclist([P|Tail], A, Total) :- partsacc(P, A, Hp), partsacclist(Tail, Hp, Total).- first clause

partsacclist([], A, A).is the boundary case which is result of accumulated list of subparts (A). - second clause

partsacclist([P|Tail], A, Total) :- partsacc(P, A, Hp), partsacclist(Tail, Hp, Total).The recursive case callpartsaccto find subparts of next eleemnt on the given list. Recursive goal deals with the remainder of the list. - Second clause 2nd argument (

A) becomes the accumulator for thepartsaccgoal to give resultHpwhich becomes the accumulator for the recursive goal.

- first clause

- Side effect with accumulator is the output list is in reverse order to the original list. For bicycle parts, this reversal is ok but it is not ok for English sentences. Bcos for every basic part, a new accumulator is created which has this part appending to to the end of list

.... partsacclist(Tail, Hp, Total)..

- Len of list without accumulator:

- Difference lists to overcome accumulator order reversal problem with 2 arguments

- one argument for "result so far"

- one argument for "hole where further info can be plugged into for final result"

[a, b, c|X] X- With a plug hole to sequence the result in order:

/* Changes with plug hole to ensure accumulator results is not reversed */ partsof(X, P) :- partsacc(X, P, Hole), Hole = []. /* alternatively partsacc(X, P , []). */ partsacc(X, [X| Hole], Hole) :- basicpart(X). partsacc(X, P, Hole) :- assembly(X, Subparts), partsacclist(Subparts, P, Hole).partsofclause:partsaccis called only once bypartsof, instantiate theHolewith [] to terminate the difference list. Thispartsacc(X, P, Hole), Hole = [].means that the very last hole will be filled with[]even before the list contents are known.partsaccfirst clause returns a difference list with the objectXas first argument if it is a basic part.partsaccsecond clause is for assemblies. It- find the

subpartslist - delegate traversal of list to

partsacclist, passing the 2 requistie arguments making the difference --PandHole. This in turn usepartsacc(specficially... partsacc(P, Total, Hole1),inpartsacclistto list subparts using the difference list viaTotalandHole1. - while still on

partsacclistwhich was extended frompartsacc,partsacclist(T, Hole1, Hole).is essentially the recursive goal to return the portion of difference list starting atHoleand ending atHole. - Result: list between

TotalandHoleis result of secondpartacclistclause "weaving" together partial results.

Traversal in partacclist - Difference List (ordered accumulator)

- find the

- Ch04 Backtracking and the "Cut"

- Multipple solutions

/* Dance Party */ possible_pair(X, Y) :- boy(X), girl(Y). boy(john). boy(marmaduke). boy(bertram). boy(charles). girl(griselda). girl(ermintrude). girl(brunhilde). ?- possible_pair(X,Y). X = john, Y = griselda ; X = john, Y = ermintrude ; X = john, Y = brunhilde ; X = marmaduke, Y = griselda ; X = marmaduke, Y = ermintrude ; X = marmaduke, Y = brunhilde ; X = bertram, Y = griselda ; X = bertram, Y = ermintrude ; X = bertram, Y = brunhilde ; X = charles, Y = griselda ; X = charles, Y = ermintrude ; X = charles, Y = brunhilde.- Prolog produces solutions in this order bcos

- first satisty the goal boy(X) ie John, then the girl(Y) ie griselda.

- With

;for backtracking, Prolog attemps to re-satisfy the girl goal to satisfy the possible_pair goal. This brings us to to girl ermintrude giving the pair john and ermintrude as 2nd solution. - Eventually at john and brunhilde, the place-marker is at the the end of database and the next time, the goal fails. Now it tries to re-satisfy boy(X). Since the place-marker was earlier placed at the first boy fact, the next solution would be the second boy marmaduke.

- Upon satisfying the second boy for the boy goal, Prolog attempts to satifsy the girl(Y) goal from the start again ,ie griselda the first girl. So the next 3 solution is marmaduke and the 3 different girls.

- On the following attempt, girl goal cannot be re-satisfied again and we find another boy and begin search for girl from scratch.

- At the end, no more solution for girl goal and no more solution for boy goal such that the program cannot find anymore pairs.

- Prolog produces solutions in this order bcos

- The "Cut"

- tells Prolog which previous choice it needs not consider again when it backtracks through the chain of satisfied goals. (Save memory and time).

- Note this suceeds immediately and cannot be re-satisfied. (side-effects)

- "Cut" alters the flow of satisfaction

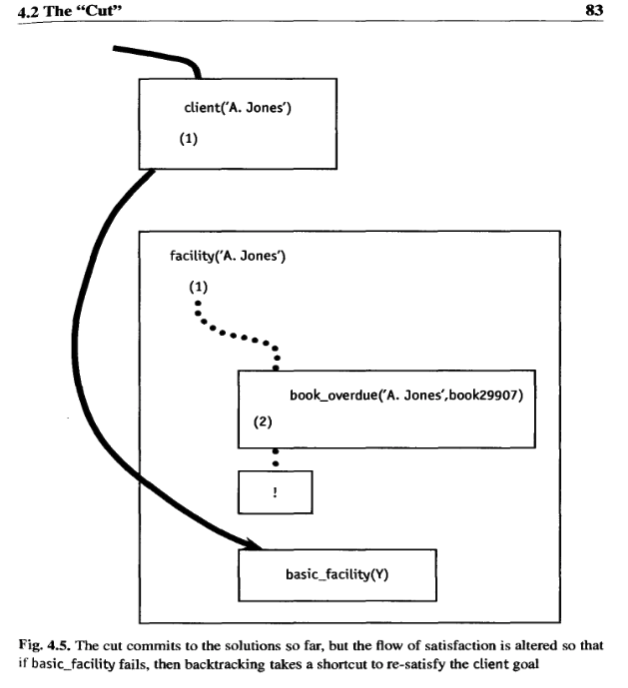

Cut limits the facility to basic facility out of all available facilities (general and basic)

- "Cut" changes the flow of satisfaction path so as to avoid all the place markers between the facility goal (comprising "basic" and "additional") and the cut goal("basic") inclusive. Thus if backtracking later retreat past this point, the facility goal will immediately fail. Result: alternative solutions for goal book_overdue('A. Jones', Book).

- Summary effect: If there is overdue book, only the basic facilities is available to the client. No need to go through all the overdue books nor any other rules about facilities.

- When a cut is encountered as a goal, commitment is made only to all choices made since parent goal (the

!box) was invoked. All other alternatives are discarded such that attempt to re-satisfy goal between parent goal and cut goal will fail. - In

foo, Prolog will backtrack among goals a, b, and c until the success of c causes the "fence" to be crossed to the right to reach goal d. Then backtracking can occur among d,e, and f, maybe safisfying the entire conjunction several times. But if d fails, the "fence" is crossed to the left, then no attempt will be made to re-satisfy goal c: the entire conjunction of goals fail and the goalfooalso fail.foo :- a, b, c, !, d, e, f.

- "Cut" uses

- Right rule found for a particular goal. The "cut" says "if you get this far, you have picked the correct rule for this goal."

- For telling the systems where to fail a particular goal immediately so it won't try for alternative solutions. "Stop trying if you get to here."

- To terminate backtracking looking for alternative solutions. "If you get to here, you have found the only solution to this problem, no point ever looking for alternatives."

- "Cut" example

- Recursive example

sum_to(1,1) : !. sum_to(N, Res) :- N1 is N - 1, sum_to(N1, Res1), Res is Res1 + N.- first clause = boundary condition for 1 where result is also 1.

- second clause = recusion where new goal is 1st argument is one less again until boundary condition is reached.

- Prolog will try to match the number agst 1 first and try the second rule if this fails ie the second rule are for non-1 numbers. But actually both rules allows for

sum_to(1, X).so we need to specify in first rule a "cut" to say never remake decision about which rule to use for sum_to goal ie only get this far with number = 1 - Ex 4.1 Using the above, the program will run into an infinite loop as it toggle between first and second clause for N = 1 SO it needs a condition. The improved solution is

sum_to(N,1) :- N =< 1, !. sum_to(N, R) :- N1 is N - 1, sum_to(N1, R1), R is R1 + N.- When condition is true, go for 1st clause and no more recursive goals. If false, then go for second clause. (Cut purpose)

- only if with

\+.\+Xsuccees only if X, when seen as a Prolog goal fails. ie\+Xmeans that "X is not satisfiable as a Prolog goal." Two alternative for when X is not 1:/* more alternatives with \+X for X is not satisable */ /* OPTION 1 with \+ */ sum_to(1,1). sum_to(N,R) :- \+(N = 1), N1 is N-1, sum_to(N1, R1), R is N + R1. /* OPTION 2 with \+ */ sum_to(N,1) :- N =< 1. sum_to(N,R) :- \+(N =< 1), N1 is N - 1, sum_to(N1, R1), R is N + R1.- More replacement options

\+(N=1)can be replaced byN\=1\+(N=<1)can be replaced byN>1

\+are preferred over cuts as they are easier to understand. But need to ensure\+involves showing that it is a satisfiable goal.- Weigh against complexity to use

\+or!- Hard to understand and may even end up satisfying B twice for

Band\+ BA :- B, C. A :- \+B, D. - Easier to understand incidentally with cut

A :- B, !, C. A :- D.

- Hard to understand and may even end up satisfying B twice for

- More replacement options

- Cut can make more sense esp when appending empty list to front of another list for efficiency reasons.

- This is inefficient bcos of backtracking to satisfy append([],[a,b,c,d],X) goal.

appennd([], X, X). append([A|B], C, [A|D]) :- append (B,C,D). - This cut improves efficiency

appennd([], X, X) :- !. append([A|B], C, [A|D]) :- append (B,C,D).

- This is inefficient bcos of backtracking to satisfy append([],[a,b,c,d],X) goal.

- Recursive example

- cut-fail combination Fail means the goal always fail and causes backtracking, similar to trying to satisfy a goal for a predicate with no facts or rules. To stop finding alternatives bcos RECALL: during BACKTRACKING, Prologs tries to re-satisfy EVERY goal that has suceeded. Insert a cut (to freeze the ddecision) before failing See 04.Backtracking_and_the_Cut/taxpayer.pl.

- goal for someone being an average taxpayer can be abandoned if the spouse earns more than 3000

average_taxpayer(X) :- spouse(X, Y), gross_income(Y, Inc), Inc > 3000, !, fail. - if pernsion is < P, then the person has no gross income

gross_income(X, Y) :- gross_salary(X, Z), investment_income(X, W), Y is Z + W.

- goal for someone being an average taxpayer can be abandoned if the spouse earns more than 3000

- Call predicate

\+: treats argument as goal to satisfy it. Below means for first rule to be applicable it P can be shown and second to be applicable otherwise.\+P :- call(P), !, fail. \+P.- ie If Prolog can satisfy call(P), it should thereupon abandon satisfying the + goal.

- OTHERWISE if it cannot show call(P), then it never gets to the cut. Bcos the call(P) goal fail, hence backtracking begins and Prolog finds the second rule. This results in goal +P succeeding when P (indicated by call(P)) is not provable.

- Terminate a "generate and test"

- "Generate": process of generating acceptable solutions(success) during backtracking (vs when no more solutions can be found(failure)).

- "Test" : checking whether the alternative solution(s) generated is acceptable.

- In 04.Backtracking_and_the_Cut/tic_tac_toe.pl

line(b(X,Y,Z,_,_,_,_,_,_),X,Y,Z). /* top row */ line(b(_,_,_,X,Y,Z,_,_,_),X,Y,Z). /* second row */ line(b(_,_,_,_,_,_,X,Y,Z), X,Y,Z). line(b(X,_,_,Y,_,_,Z,_,_),X,Y,Z). line(b(_,X,_,_,Y,_,_,Z,_),X,Y,Z). line(b(_,_,X,_,_,Y,_,_,Z),X,Y,Z). line(b(X,_,_,_,Y,_,_,_,Z),X,Y,Z). line(b(_,_,X,_,Y,_,Z,_,_),X,Y,Z). /* Case where x-player is threatening to win on next move */ /* cut means 1 threat is enough to force a move */ forced_move(Board) :- line(Board,X,Y,Z), threatening(X,Y,Z), !. threatening(e,x,x). threatening(x,e,x). threatening(x,x,e).- program tries to find a line with 2 occupied squares and report a forced_move situation.

- In forced_move, the goal of line(Board,X,Y,Z) is the "generator" of possible lines which has many possibilities.

- In forced_move, the "tester" goal is threatening(X,Y,Z) which looks for 1 of 3 possible threatening patterns.

- Thus the sequence is:

- line propose a line

- threatening check if line is threatening. If forced, forced_move goal succeed.

- otherwise, backtracking kicks in to find another line.

- If we get to the point when line can generate no more lines, then forced_move goal correctly fails ie no forced move.

- But mostly, there is no alternative so save on effort for forced_move to search thru before itself failing. So put a "cut" at the end of forced_move. EFFECT is freeze the last successful line solution. This means when looking for forced moves, only the first solution is important.

- In 04.Backtracking_and_the_Cut/4.3.3b_divide.pl, the result of dividing 27 by 6 is 4 bcos 4 * 6 is less than or equal to 27, and 5 * 6 is greater than 27.

divide(N1, N2, Result) :- is_integer(Result), Product1 is Result * N2, Product2 is (Result + 1) * N2, Product1 =< N1, Product2 > N1, !.- generator =

is_integer - tester = rest of goals bcos for specific N1, N2,

divide(N1, N2, Result)can only succeed for 1 possible value for Result. - so although

is_integercan generate infinitely many candidates, the tester will limit solution to 1. And the cut purpose is to stop trying after we have aResultthat passes the test. - The cut stop backtracking from finding alternatives for

is_integer.

- generator =

- Cut problem. Putting cut at the wrong place could give a wrong result ie no solution when there are. So it is impt to be certain how the rules work. p96 shows

- Freezing everything saying no further solutions altho there are actually other solutions.

append([], X, X) : -!. append([A|B], C, [A|D]) :- append(B,C,D). ?- append(X, Y, [a,b,c]). will return X = [], Y= [a,b,c] only. - 04.Backtracking_and_the_Cut/4.4_cut_problem.pl is intended to say everyone has 2 parents expect adam and eve. The cut prevents backtracking to 3rd rule of the person(X) being adam or eve. See tHe 2 options as alternative.

number_of_parents(adam, 0). number_of_parents(eve, 0). number_of_parents(X, 2) :- \+(X = adam), \+ (X = eve). - summary: review all the uses of cut to see the rules are used correctly.

- Freezing everything saying no further solutions altho there are actually other solutions.

- Multipple solutions

- Ch05 Input and Output

- Using atoms in list for a database to facilitate searches. Here the headlines are in lists of atoms to help find the dates when certain key events happen.

event(1505, ['Euclid', translated, into, 'Latin']). event(1510, ['Reuchlin-Pfefferkorn', controversy]). event(1523, ['Christian', 'II', flees, from, 'Denmark']). /*goal when(X,Y) succeeds if X is mentioned in year Y*/ when(X,Y) :- event(Y, Z), member(X, Z). ?- when('Denmark', D). D = 1523. - Reading and writing

- program waits for me to type input means reading the input

- progrma displays output to me means writing the output.

read+ SOMETHING +.+(enter)- uninstantiated X will caused next term to be read and instantiated.

- read predicate cannot be re-satisfied and succeeds at most once. It cannot re-satisfy once it reach backtracking.

- read is special

hello1(Event) :- read(Date), event(Date, Event). get event by enter Date bcos read is in the goal ?- hello1(X). |: 1523. X = ['Christian', 'II', flees, from, 'Denmark'].

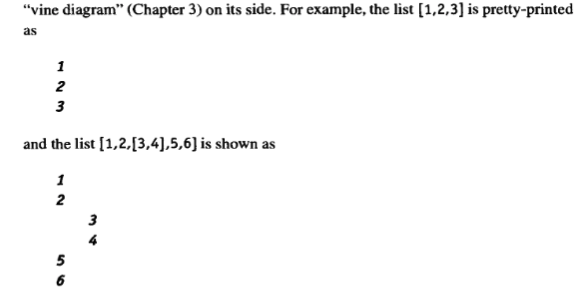

nl= new line. succeeds only oncewritesucceeds only onceppfor pretty print. Elements in list get displayed as a column and list in a list get displayed as a indented column like a parent-child token of ud-gf. This is done by 05.Input_and_Output/5.1.2_pretty_print.pl

- how

ppxworks:pp([H|T], I) :- !, J is I + 3, pp(H,J), ppx(T, J), nl. pp(X,1) :- spaces(I), write(X), nl.- second arg of pp is the column counter. So the top level goal to display a list would be pp(L,0) initialising the counter to 0.

- 1st clause handles special case whereby first argument is a list then the column counter set to 3 and then pretty print the head of list which is a list itself

- then

ppxaligns the tail of the list in the same column. - second clause of

ppfor pretty print somehting that is not a list.ie indent to the specified col, usewriteto display, and then new line.nlto terminate each list with a new line.

- the predicate spaces defines the number of "space" / spacing by the argument of spaces

- To get any history headlines that mentions "England" in 05.Input_and_Output/5.1.1_events.pl

phh([]) :- nl. phh([H|T]) :- write(H), spaces(0), phh(T). - To extract event with the word 'Latin' using backtracking to search the database. Whenever member goal fails, an attempt is made to re-satisfy the event.

?- event(_, L), member('Latin',L), phh(L). EuclidtranslatedintoLatin L = ['Euclid', translated, into, 'Latin']- write vs write_canonical : write_canonical auto handles precedences of operators. Some prolog systems call it display

?- write(a+b*c*c), nl, write_canonical(a+b*c*c), nl. a+b*c*c +(a,*(*(b,c),c)) true.- To make interactive program to list headlines and using phh to display a list of atoms for question with hello2 in 05.Input_and_Output/5.1.1_events.pl. Steps:

- display question

- read to read the date like hello1

- phh to display the retrieved headline

- noticed the first phh shows it can display any list of atoms regardless of its origin

- ps: remember ' ' is for capital words to not mistaken them as Variable and bcos of ? at desire*/

in .pl hello2 :- phh(['What', date, do, you, 'desire? ']), read(D), event(D, S), phh(S). ------------------------- in terminal after swipl ?- hello2. Whatdatedoyoudesire? |: 1510. Reuchlin-Pfefferkorncontroversy true.

- Checking character errors:

check_lineread everything until\nand which then compare every pair of char for known "typing errors" ie "qw" and "cv" with its X instantiated to 'yes' or 'no'.rest_lineis always called after a character is read. Its clauses do:- check end of line reached

- match known typing error in previous and current characters.

- keep checking for next character as not known typing error is spotted at this point.

put_chardisplay whatever character?- put_char('h'), put_char('i'). hi true. ?- put_char('h'), put_char('i'), nl, put_char('Y'), put_char('o'), put_char('u'). hi You true.correct_linecorrect a known typing error when it is detected otherwise the characters are simply copied out unchanged but its limitations are- limited to errors with only 2 adjacent char

- coerce the 2 adjacent errorneous chars into 1 single character via

typing_correction.

correct_rest_lineoutput is the corrected text with character in its first argument. "lawn mower"

- Sentences

- Special characters quote

" " ''and- - Space character between words

- Word forming character ',' , '.', ';', ':', '!'

- End of sentence ',' , '?', '!'

- Everything to lowercase

- avoid backtracking over a use of get_char to avoid losing the character it reads in.

- Special characters quote

- Using atoms in list for a database to facilitate searches. Here the headlines are in lists of atoms to help find the dates when certain key events happen.

1Regina/Programming_In_Prolog

William F. Clocksin, Christopher S. Mellish-Programming in Prolog-Springer (2003).pdf: Notes and Exercises

Prolog