Authors: Doug Mill, Michael Lee, and Carlos Mccrum

Our task is to build inferential classification models for the Vehicle Safety Board of Chicago. We cleaned and formatted our data provided by the City of Chicago containing crashes, vehicles and people relating to crashes from 2016 to 2020, we then modeled the primary contributory causes of car accidents into two categories. We used an iterative modeling approach and incorporated several classification models to see if we could find what crashes were preventable. Our recommendations include investing in driver education for certain age groups and fixing certain road conditions that could cause a crash.

Our stakeholder is the Vehicle Safety Board of Chicago. They are launching a new campaign to reduce car crashes. Our task is to build an inferential model to find out which crashes were preventable and not. We labeled ‘Preventable’ as crashes that could have easily been avoided. Not following traffic laws and negligent driving would fall under this category. ‘Less Preventable’ are crashes that would require a substantial amount of money, time, and labor to fix. Bad road conditions, vision obscurity, and bad weather conditions would fall under this category.

Our stakeholder, the Vehicle Safety Board, has the resources to focus on large projects. Therefore, we to focused on 'Less Preventable' crashes as these projects were not related to human error. We also wanted to target the age groups most involved with crashes.

The Vehicle Safety Board would like to better understand the causes of crashes in the Chicago area. That way, they can focus their campaign on potentially preventing some of those crashes in the future. We used data from the City of Chicago Data Portal, which contains information about Chicago Car Crashes from January 2016 to December 2020. The target variable was “primary contributory cause” as recorded by the police officer at the scene of the crash. Some of our inferential variables “defect road”, “bad road conditions”, and “obscured vision” will help us in our analysis to see if a crash was preventable.

We combined 3 different datasets that we found on the City of Chicago website. Those datasets were crashes, people, and vehicles.

Crashes details various contributory causes of the accidents such as traffic devices and road conditions. For this dataset, we dropped all unnecessary columns such as injury severity and street direction. After dropping missing values we could not reasonably populate ourselves, we were left with a dataset of ~950,000 entries. Then, we mapped all the object data types into an int or float 64 to pass into our model. Finally, we created a Target column to label the crashes as Preventable or Less Preventable.

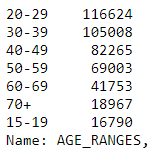

Next, we worked on the people dataset. For the people dataset, we dropped 25 unnecessary columns that we think would not influence the primary contributory cause of an accident. We removed remaining null and unknown values. We then binned by age, and this is where we saw that most of the drivers involved in accidents were between the ages of 20-39. We then converted the remaining features into binary variables. We joined this with the crash dataset and mapped the features into our target.

Lastly, we worked on the vehicle dataset. For this dataset, we only kept the vehicle defect and number of passengers variables. We turned these into binary variables. Our cleaned CSV's are in Cleaned CSVs.

Our data preparation process can be found in our Data Cleaning Notebook located in the appendix.

Our target had a distribution of .75 to .25. The 2 categories in the target are 0 for preventable and 1 for not preventable. Because our class balance was 3:1, we did not SMOTE the minority class.

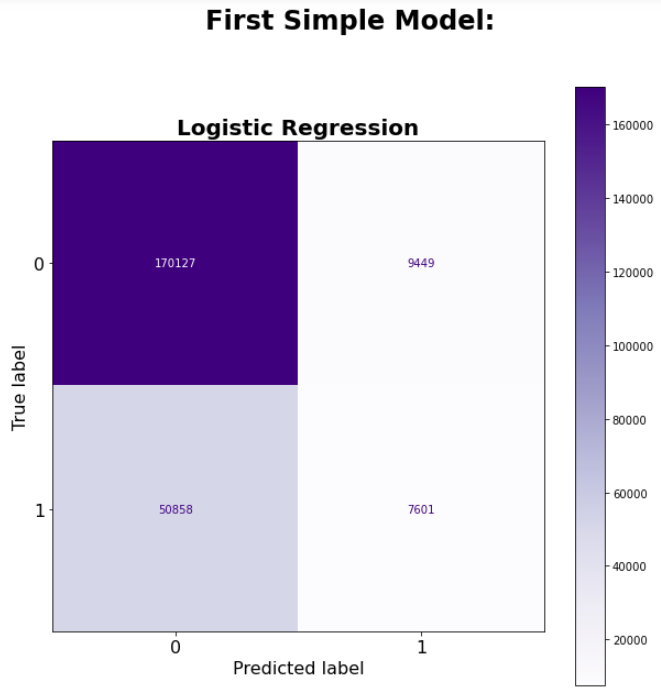

We modeled the data through iterative modeling. We used a logistic regression model as our first simple model.

We graded this model on accuracy score and it resulted in 0.7466465015648959. This was our lowest score. Therefore we used this as our baseline. It was something simple and understandable yet still decent and something we could build on.

We also graded this model on precision and got a result of 0.45.

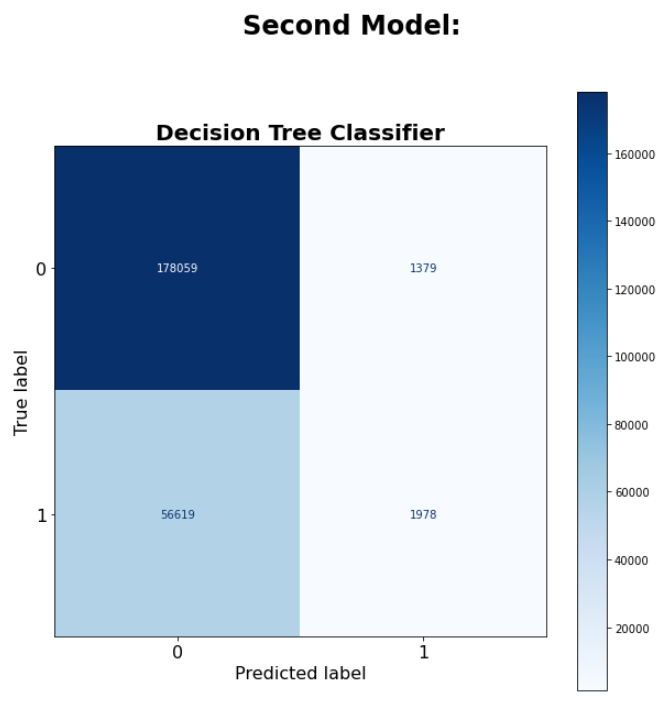

For our second model, we created a Decision Tree Classifier that scored slightly better than our simple model. We used a RFE to determine the most important features and iterated with GridSearch to find the best parameters. We found bad road conditions, road defects, traffic device failure, obscured driver vision, and driver error were the most important features. We ran a decision tree with these features as well as all features. Important features: 0.7555023420925494 All features: 0.7563467557291995 We then ran a grid search, which scored roughly the same. We graded this model on precision and got a score of 0.6. When we added RFE to this model, the precision rose to 0.63.

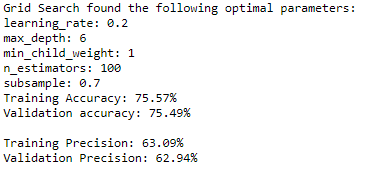

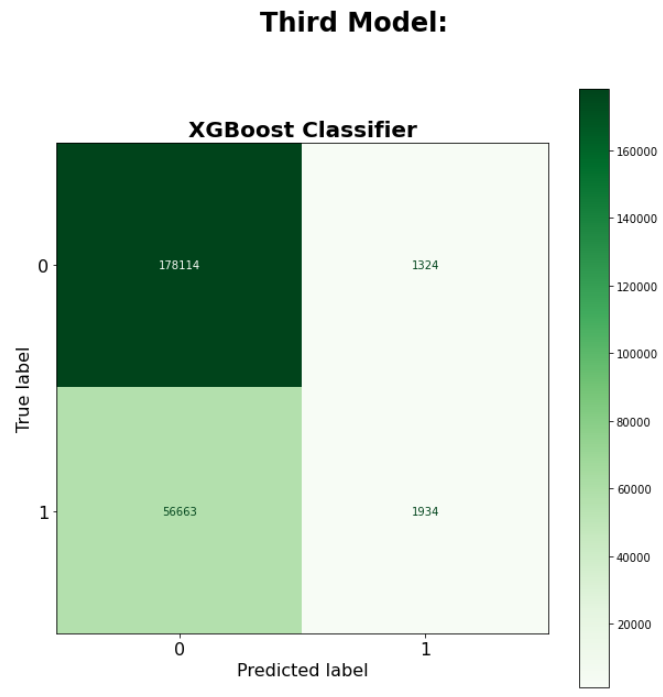

Lastly, we used a XGBoost classifier with GridSearchCV to find the best model. This model performed very similarly:

Our best model had an accuracy score of 75%. It had a precision score of 63%. Our precision score is out of all the times the model said it was a less preventable crash, how many times were actually a less preventable crash. Iterative modeling did well to improve precision. By directing the Vehicle Safety Board to certain hotspots of defective roads, we could make a substantial and immediate impact on accidents.

The results of our model indicated that most of the crashes were Preventable. By involving drivers with driver education, we could address some of these preventable crashes. It would be particularly prudent to focus on driver education for ages 20-39. This would be an efficient and effective use of funds for the Vehicle Safety Board of Chicago.

We recommend investing in fixing defective roads. This was the bigger contributor to less preventable crashes, followed by poor visibility, and vehicle defects. Our largest age range of drivers involved in crashes is 20-39. The biggest non-driver preventable issue this cohort faced was also defective roads. We discovered in mapping road defects that the northern side of Chicago has more crashes caused by this than the southern side. We recommend fixing up road defects in northern Chicago. We also suggest a driver education campaign targeting a younger audience between ages 20-39. We could potentially incentivize this cohort. Lastly, we could target specific hot spot areas that are known to be a magnet for crashes.

See the full analysis in the Jupyter Notebook or review this Presentation.

For additional info contact Michael Lee, Carlos Mccrum, and Doug Mill.

You are in the README.md right now. If you want to take a look at our Jupyter Notebook, go to the 'Chicago_Car_Crash_Notebook.ipynb' to find our data science steps for you to replicate! Within the 'appendix', you will find our data cleaning steps that we used for our final model. The 'data' folder contains the several datasets we merged together as well as the cleaned version of said files. 'images' folder contains the images used within this README. We hope you find our research informative!

├── appendix

├── data

├── images

├── .gitignore

├── .gitattributes

├── Chicago_Car_Crash_Notebook.ipynb

├── Chicago_Car_Crash_Presentation.pdf

└── README.md