// numbers

7.43

// Very small/big numbers can be represented using exponents (e)

2.4e8 // same as 240000000

+ // addition

* // multiplication

- // subtraction

% // remainder or modulo

// Creful using these two

Infinity // + infinity

-Infinity // - infinity

NaN // not a number (confused)

// As long as the the quotes at the start and the end of the string match

// String can be represented in 3 ways

"I am a string"

'This is another string'

`Me too, but I am special` // template literals, allow for value-embedding

`5+5 is ${5+5}` // code

"5+5 is 10" // output

// Unary operator

typeof 4; // code

"number" // output

typeof "S" // code

"string" // output 3 < 2 // less than

false // output

1.01 > 1 // greater than

true "z" > "a" // is "z" greater than "a"

true // outputStrings are ordered alphabetically. "a" being the 'smallest' to "z" the 'largest'.

"Z" > "a" // is capital "Z" greater than "a"?

false // output Well, with the exception of uppercase letters. They are always “less” than lowercase ones.

To visually see it from "largest" to "smallest":

z > y > x > w > v > ... b > a > Z > Y > X > ... > B > A

(...) The three dots here simply indicate an intentional omission of the letters but the pattern should be clear.

So, how will javascript compare longer strings (i.e words, sentences)?

Javascript goes over the string from left to right, comparing the unicodes (characters) one by one:

- Compares first characters of both words, decides whether one is greater or they're both equal.

- When both firsts are equal, goes on to compare the next two.

- Repeat until the end.

- If both strings end at the same length, then they are equal. Otherwise, the longer string is greater.

>= // greatr than or equal to

<= // less than or equal to

!= // not equal to Note: There is only one value in JavaScript that is not equal to itself, and that is NaN.

console.log(NaN == NaN)

false // this is bc it's the result of nonsensical computation and that can be different every time.Applied to Boolean values.

- and:

&& - or:

|| - not:

!

! flips the value behind it.

!true // read: not true

false // output: produces false null and undefined are empty values and the difference can be ignored.

Javascript tries to please everyone. There's a cost to that "openness".

12 * null // multiplication

0 // output

"51" - 1 // the string "51" minus 1

50 // outputs the number 50

"5" + 1 // string "5" plus 1

"51" // outputs the string "51"

"five" * 2 // string "five" times 2

NaN // output 'Not a Number'This is just Javascript being Javascript. This is called type coercion. JS notices an operation and tries its "best" to satisfy the instructions by quietly converting the values.

In the first case, null becomes 0. In the second case, it recognizes "51" as a string but also realizes that - is an operator on numerics and 1 is also a numeric value. Whereas in the third case, the + operator is used for concatinating two strings together and "5" is already a string, so it makes sense to cast 1 as a string as well.

== tests whether both values are the same.

=== tests whether the type and content matches.

!== Will return true if they're not equal in type and/or content.

Binding or variable assignment can be used interchangeably. JS uses three keywords for binding (creating a new variable), let, var (short for "variable") and const (short for "constant").

let name = "Ahmeda"; // 'let' connects the string "Ahmeda" to the binding (variable) 'name'.

// multiple bindings at the same time

let lastName = "Cheick", hobby = "Playing Soccer";

// using const to assign an age binding

const age = 25;const is used to define a constant variable which points to its value for as long as it 'lives'. So probably setting age to 25 with const isn't a good idea if I plan on living longer!

Note: var is the way variables were declared prior to 2015 in Javascript and it does mostly the same things as let, except that it's visible outside of its defined scope.

if keyword executes or skips a statement depending on the value of a Boolean expression.

if (age == 25) {

console.log(`You are ${age} years old!`);

}When the statement wrapped in braces () isn't true, the program skips. Adding an else keyword lets it know what to do in that case.

else {

console.log(`You are not ${age}!`)

}You can check whether multiple expressions are true by chaining else ifs.

if (expressionOne) {

doSomething();

} else if (expressionTwo) {

doSomethingElse();

} else if (expressionThree) {

doAnotherThing();

} else (whenNothingWorks) {

wellDoThisThen();

}Note: Indentation in javascript is simply to enhance code readibility unlike Python which "breathes" it. You could write your program in a single line if you wanted to. Don't do it!

Since you insist:

if (expressionOne){doSomething();} else if(expressionTwo{

doSomethingElse();}else if (expressionThree){doAnotherThing();} else (whenNothingWorks{wellDoThisThen();}A simple for loop:

for (let number = 0; number <= 6; number + 2) {

console.log(number);

}A for loop consists of three parts, the for keyword itself, the statement in parentheses and finally the body whithin the {} which contains the instructions of what to do at every iteration.

The statement (let number = 0; number <= 6; number +2) does three things seperated by two semicolons. It initializes the loop, checks if it must continue and how it must update.

Switch allows you to put a number of scenarios (case labels) and javascript will start executing at the label that corresponds to the value that switch was given, or defaults when no matching value was found.

Let's say, depending on your budget you want to go somewhere for a vacation.

let budget = parseInt(prompt("What's your budget"));

switch (true) {

case budget < 100:

console.log("Take a walk around the block.");

break;

case budget >= 1000:

console.log("let's to the beach");

break;

case budget > 5000:

console.log("Hello, Vegas!")

default:

console.log("Let's discuss your finances.");

break;

}Note: Don't forget the break statement, or else it will execute code you don't want.

Arryas:

Arrays (lists) in Javascript are declared using square brackets.

let someArray = [2,57,63,5];Every element has an index, starting from 0 and can be retrieved this way someArray[0].

You can access its property using a dot . or brackets.

someArray.length or someArray["length"] do the same thing.

Note: Properties that contain functions are called methods.

someArray.push(76); // adds the number 76 at the end of the array and reutrns the new length of the array

someArray.pop(); // removes the last element and returns it.

76 // output

// the corresponding methods for adding and removing elements

// at the start of an array are called unshift and shift

someArray.shift(); // removes first element 2 and returns it

someArray.unshift(2); // adds the numb 2 at the start of the array.Note: To search for a specific element in an array we use indexOf method. Going from the start to end of the array it will return the index of that element when found. Otherwise, it will return -1.

To search from end to start instead we use lastIndexOf. Also, they both take a second optional argument indicating where to start searching from.

console.log([1, 2, 3, 2, 1].indexOf(2));

// → 1

console.log([1, 2, 3, 2, 1].lastIndexOf(2));

// → 3

console.log([1, 2, 3, 2, 1].indexOf(2,2)) // notice how it starts searching only from index 2.

// → 3

console.log([0, 1, 2, 3, 4].slice(2, 4)); // slice method used to return an inner array based on a range of indices. The second number is exclusive

// → [2, 3]The concat method can be used to glue arrays together to create a new array.

Objects

Objects are a collection of properties seperated by commas.

let someObject = {

"type": true,

"day": "Sunday",

}Properties whose names aren't valid variables need to be quoted.

You can assign new values using the = operator. someObject.date = "10/06/2019". If it already existed, it will replace its value.

delete someObject.type; // deletes the property 'type'

console.log("type" in someObject); //checks whether 'type' still exists

false // console output

Object.keys(someObject); // return the properties (keys)

["day","date"] // output

Object.values(someObject) // similarly this one return the values

["Sunday", "10/06/2019"] // output

Object.entries(someObject) // returns each key-value pair as an array.

someObject.date // the key can also be used to access the value

"10/06/2019" // output Functions in Javascript are objects and possess all its capabilities.

const makeSomeNoise() = function() {

console.log("Honk Honk!");

};

makeSomeNoise();

"Honk Honk!" // console output They can take multiple parameters or no parameter at all. Its body which is contained in the braces {} gets executed every time the function is called.

const addNumbers = function (numb1, numb2, numb3) {

console.log(numb1 + numb2 + numb3);

};

addNumbers(1, 2, 3);

6 // console outputThe values of those parameters are assigned by its caller. Then a return statement determines the final output of that function.

Note: Each binding (variable) in JS has a scope where it's 'visible'. Variables with global scopre are visible and can be used anywhere in the program. Variables created inside a function are only visible within that function, they are local variables. Unless declared using the var keyword, in that case they are gloabl. There are also degrees to locality and functions can be nested.

function addNUmbers(n1, n2) {

return n1 + n2;

}Note: Function declaration doesn't require a semicolon after the function and it works differently.

// logging out half a quote and a function

console.log("'Always remember that you are absolutely unique." + secondPart());

function secondPart() {

return " Just like everyone else.' -Margaret Mead";

}If you haven't noticed, we called the function secondPart() before we've even declared it. This is because function declarations are not part of the top-to-bottom execution you're used to. Those functions get moved to the top of their scope and can be used anywhere within tha scope.

The arrow => comes after the parameters then followed by the function's body. You can remember it this way "This list of params => will produce the following".

const addNumbers = (n1, n2) => {

return n1 + n2;

};

// these two do the same thing.

const squared = (x) => { return x * 2; };

const squared = x => x * 2; // you can omit the braces {} for a single expression in the body

// when an arrow function has no params

const saySomething = () => {

console.log("It was over my head.");

};function addition(x1, x2) {

return x1 + x2;

}

console.log(addition(2, 2, "It's a beautiful day!"));Note: if you pass too many arguments, they will get ignored. However, when you pass too few arguements, they will get replaced with undifined.

The = operator is used as default in case an argument isn't passed.

function addition(x1, x2 = Infinity) {

return x1 + x2;

}

console.log(addition(2));

Infinity // console output We pass a function as an argument to another function that might, at a later point in execution, call the passed-in function.

function uselessFunction (callMeBack()) {

return callMeBack();

}As you know well by now, methods are properties that hold function values. We call them this way someObject.method(). A variable called this automatically points at the object it was called on. Let's slowly build on this.

let dog = {};

dog.speak = function (speech) {

console.log(`The dog says: ${speech}`);

}

dog.speak("I can speak now!");

"The dog says: I can talk now!" // output Nothing new there! But watch closely:

function speak(speech) {

console.log(`The ${this.type} says '${speech}'`);

}

let dog1 = {

type: "Chihuahua",

speak

};

let hungryDog = {

type: "boxer",

speak

};

hungryDog.speak("I am hungry");Think of this as an extra parameter which isn't passed explicitly! However, if you want to pass it, you use a function's call method which takes this as its first argument and the rest arguements passed to it as normal arguements.

speak.call(hungryDog, "Burp!");

"The boxer says 'Burp!'" // output

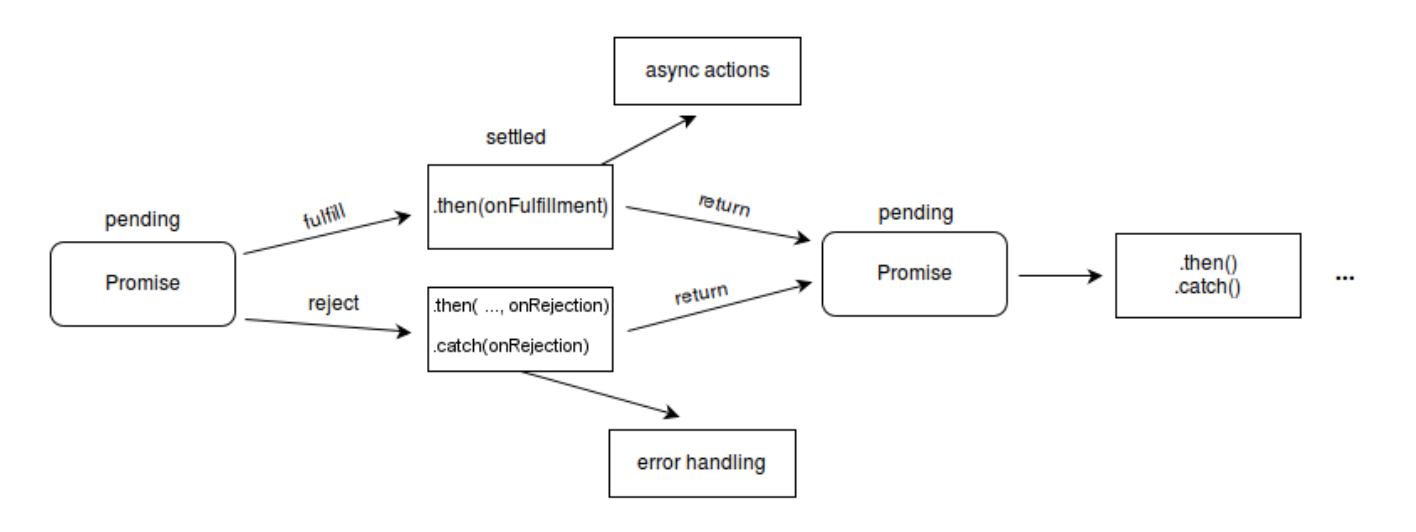

Javascript relies a lot on asynchronous computations. A promise is a placeholder for a value that we don’t have now but will have later. Well there ar only two possible outcomes; we either make good on our promise and we get the data as a value or something unexpected happens in that case we get an error.

var promise1 = new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

setTimeout(function () {

resolve('foo');

}, 3000);

});

promise1.then(function (value) {

console.log(value);

// expected output: "foo"

});

console.log(promise1);To create a promise we use the built-in Promise constructor, to which pass a function. This, executor function, has two parameters. resolve and reject.

This code (copied from documentation) uses the promise by calling the built-in then method on the Promise.

Let's say you're pulling a JSON file of all the troops and you want to send orders to the first soldier (at index zero).

getJSON("data/troops.json", function(err, troops){

getJSON(troops[0].location, function(err, locationInfo){

sendOrder(locationInfo, function(err, status){

/*Process status*/

}) })

});This code is difficult to understand and adding new steps can be very painful. Also, some of these steps can be done in parallel. Let's say we want to set a plan in motion that require us to know which soldier we have at our disposal, the plan itsel, and the location where our plan will play out, we could write something like this.

var troops, mapInfo, plan;

d3.json("data/troops.json", function (err, data) {

if (err) {

processError(err);

return;

}

troops = data;

actionItemArrived();

});

d3.json("data/mapInfo.json", function (err, data) {

if (err) {

processError(err);

return;

}

mapInfo = data;

actionItemArrived();

});

d3.json("plan.json", function (err, data) {

if (err) {

processError(err);

return;

}

plan = data;

actionItemArrived();

});

function actionItemArrived() {

if (troops != null && mapInfo != null && plan != null) {

console.log("The plan is ready to be set in motion!");

}

}

function processError(err) {

alert("Error", err)

}