- To-Do List

- File hierarchy

- Requirements

- Configuration File

- Allowed Functions

- HTTP Server

- Socket

- Making a non Blocking server

- Response && Request

- 42 Tester

- Bibliography

- License

- Implement a configuration file

- Work on the tester

- Implement: "Transfer-Enconding: Chunked"

- Start Cheking every Request's header

- Stop erasing client_fd, request and response

- Return HTTP correct statuses

.

├─ 📁includes

│ └─ webserv.h

├─ 📁srcs

│ ├─ 📁classes

│ │ └─ *.cpp/&.hpp

│ └─ *.cpp

├─ 📁routes

├─ 📁public

│ ├─ 📁html

│ └─ 📁img

├─ main.cpp

├─ 📁config

├─ 📁resources

│ ├─ 📁images

│ └─ 📁simpleServer

├─ 📁testers

├─ 📁image_gallery

├─ 📁SessionManager

├─ links.txt

├─ changelog

├─ Makefile

└─ README.md

• Your program has to take a configuration file as argument, or use a default path.

• You can’t execve another web server.

• Your server must never block and the client can be bounced properly if necessary.

• It must be non-blocking and use only 1 poll() (or equivalent) for all the I/O operations

between the client and the server (listen included).

• poll() (or equivalent) must check read and write at the same time.

• You must never do a read or a write operation without going through poll() (or equivalent).

• Checking the value of errno is strictly forbidden after a read or a write operation.

• You don’t need to use poll() (or equivalent) before reading your configuration file.

• You can use every macro and define like FD_SET, FD_CLR, FD_ISSET, FD_ZERO (understanding

what and how they do it is very useful).

• A request to your server should never hang forever.

• Your server must be compatible with the web browser of your choice.

• We will consider that NGINX is HTTP 1.1 compliant and may be used to compare

headers and answer behaviors.

• Your HTTP response status codes must be accurate.

• You server must have default error pages if none are provided.

• You can’t use fork for something else than CGI (like PHP, or Python, and so forth).

• You must be able to serve a fully static website.

• Clients must be able to images files.

• You need at least GET, POST, and DELETE methods.

• Stress tests your server. It must stay available at all cost.

• Your server must be able to listen to multiple ports (see Configuration file).

In the configuration file, you should be able to:

• Choose the port and host of each ’server’.

• Setup the server_names or not.

• The first server for a host:port will be the default for this host:port (that means

it will answer to all the requests that don’t belong to an other server).

• Setup default error pages.

• Limit client body size.

• Setup routes with one or multiple of the following rules/configuration (routes wont

be using regexp):

◦ Define a list of accepted HTTP methods for the route.

◦ Define a HTTP redirection.

◦ Define a directory or a file from where the file should be searched (for example,

if url /kapouet is rooted to /tmp/www, url /kapouet/pouic/toto/pouet is

/tmp/www/pouic/toto/pouet).

◦ Turn on or off directory listing.

◦ Set a default file to answer if the request is a directory.

◦ Execute CGI based on certain file extension (for example .php).

◦ Make the route able to accept imagesed files and configure where they should

be saved.

∗ Do you wonder what a [CGI][CGI] is?

∗ Because you won’t call the CGI directly, use the full path as PATH_INFO.

∗ Just remember that, for chunked request, your server needs to unchunked

it and the CGI will expect EOF as end of the body.

∗ Same things for the output of the CGI. If no content_length is returned

from the CGI, EOF will mark the end of the returned data.

∗ Your program should call the CGI with the file requested as first argument.

∗ The CGI should be run in the correct directory for relative path file access.

∗ Your server should work with one CGI (php-CGI, Python, and so forth).

| Function | Prototype | Description |

|---|---|---|

| htons | uint16_t htons(uint16_t hostshort) |

Host To Number Short (#include <arpa/inet.h>) |

| htonl | uint32_t htons(uint32_t hostlong) |

Host To Number Long(#include <arpa/inet.h>) |

| ntohs | uint16_t ntohs(uint16_t hostshort) |

Number to Hostshort (#include <arpa/inet.h>) |

| ntohl | uint32_t ntohl(uint32_t hostlong) |

Number to Hostlong (#include <arpa/inet.h>) |

| select | int

select(int nfds,

fd_set *restrict readfds,

fd_set *restrict writefds,

fd_set *restrict errorfds, s

truct timeval *restrict timeout); |

To be Found (#include <sys/select.h>) |

| poll | int poll(struct pollfd fds[], nfds_t nfds, int timeout); |

To be Found (#include <poll.h>) |

| epoll_create | int epoll_create(int flag/size); |

To be Found (#include <sys/epoll.h>) |

| epoll_ctl | int epoll_ctl(int epfd, int op, int fd, struct epoll_event *event); |

Add modify or remove epoll things (#include <sys/epoll.h>) |

| epoll_wait | int epoll_wait(int epfd, struct epoll_event *events, int maxevents, int timeout); |

Waits for an epoll event (#include <sys/epoll.h>) |

| kqueue | int kqueue(void); |

To be Found (#include <sys/event.h>/<sys/time.h>) |

| kevent | int

kevent(int kq, const struct kevent *changelist, size_t nchanges,

struct kevent *eventlist, size_t nevents,

const struct timespec *timeout); |

Long to write rn (#include <sys/event.h>/<sys/time.h>) |

| socket | int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol); |

Creates an endpoint for comunication and return an fd for it (#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| accept | int accept(int sockfd, struct sockaddr *restrict addr, socklen_t *restrict addrlen); |

Extracts the first connection request on the queue from a socket (#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| accept | int accept(int sockfd, struct sockaddr *restrict addr, socklen_t *restrict addrlen); |

Extracts the first connection request on the queue from a socket (#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| listen | int listen(int sockfd, int backlog); |

Makes the socket passive, which makes the socket accept connections(#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| send | ssize_t send(int sockfd, const void *buf, size_t len, int flags); |

Transmits a message to a socket(#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| recv | ssize_t recv(int sockfd, void *buf, size_t len, int flags); |

Recieves a message from a socket(#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| bind | int bind(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen); |

Binds a socket name to a address(#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| connect | int connect(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen); |

Connects the socked reffered by sockedfd to the address(#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| inet_addr | in_addr_t inet_addr(const char *cp); |

Converts the ipv4 direction to into binary into binary data(#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| setsockopt | int setsockopt(int sockfd, int level, int optname, const void *optval, socklen_t optlen); |

Manipulate options of the socket(#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| getsocketname | int setsockopt(int sockfd, int level, int optname, const void *optval, socklen_t optlen); |

Returns the socked address(#include <sys/socket.h>) |

| fcntl | int fcntl(int fd, int cmd, ... /* arg */ ); |

Performs an operation on the fd based on cmd(#include <fcntl.h>) |

Libraries that we are using:

Hypertext Transfer Protocol

HTTP is a protocol, a set of rules for data transmission between computers, for fetching resources. So it is the set of rules servers and clients use to transfers documents on the web back and forth.

HTTP is a "Stateless" procotol, which means that it does not have memory of previus requests. That make users unable to walk through requests because they are not conected. Even though it is statless it is not Sessionless, which means that the server can store data of you previus request and store them as "cookies". So when you request access back to a website you visited it has info about you. Cookies are saved as HTTP Headers, which can store all kind of data request

So the last basic priciple about it is that it works based on request/response pairs. So every action starts with a request using an HTTP method, and ends with a response of a HTTP status code, along with what happened to the request, data ...

A socket is a mechanism OSs use to allow programs to access the network. A socket is independet of the network.

The workflow of a socket would be something like:

- Creating the socket

- Identifying the socket

- Make the server wait for an incomming connection

- Send/Recive messages

- Closing the socket

To create a socket we use the fucntion socket();, liste above, which returns a socket_fd.

int server_fd = socket(domain, type, protocol);All its parameters are integers: domain (or address family AF), the communication domain in which the socket will work (AF_INET, IP | AF_INET6, IPV6 | AF_UNIX, local channel, similar to pipes | ...); type, type of the service it'll be using, it varies depending on the properties of the program (SOCK_STREAM, virtual service circuit | SOCK_DGRAM, datagram service | SOCK_RAW, direct IP service), I'd recommend checking with the domain to see if the service is aviable; protocol, it indicates which protocol is gonna be used to support the socket operations, some families have multiple protocols so they can support multiple services

For a TCP/IP socket we will be using the IP family address AF_INET, a virtual socket circuit SOCK_STREAM, and since there are no variations of the protocol the last argument is 0

AF_INET: Address Family that your socket can comunicate to, in this case Internet Protocol v4 (IPv4).

SOCK_STREAM: A connection based protocol in which since the connection is established the two ends have a conversation until some end decides to end it. For example, in SOCK_DGRAM you send just one datagram, recive a respond and the comunication ends.

The TCP socket would look something like this:

#include <sys/socket.h>

...

if ((server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)) < 0){

write(2, "error\n", sizeof("error\n"));

return (1);

}Identifying or naming a socket means we bind it to an IP and a port, a transfer address. In socket this is called binding. We use bind(); function.

The socket address is defined in a socked address structure, because sockets work in many types of comunication this interface is very general. The socket address is defined by the address family. In a AF_UNIX it would create a file.

int bind(int socket, const struct sockaddr *address, socklen_t address_len);It's first parameter is the socket we just created; The second one is a sockaddr struct, which is a generic structure that allows the OS to detect the Address Family. Depending on the address family we determine what struct to use, for IP networkin struct sockaddr_in, defined in netinet/in.h

struct sockaddr_in

{

__uint8_t sin_len;

sa_family_t sin_family;

in_port_t sin_port;

struct in_addr sin_addr;

char sin_zero[8];

};Before calling bind we should fill this structure: sin_family, the address family we use for out socket (AF_INET); sin_port, the port number, you can either assing one or let your OS assing one by default (by assigning 0); sin_addr, the IP address of your machine, you can allow you OS to choose the interface by choosing the special one 0.0.0.0 or using INADDR_ANY. struct in_addr

The third parameter is just the size of the structure, it just :

sizeof(struct sockaddr_in) the code that binds the socket would look something like this:

#include <sys/socket.h>

...

struct sockaddr_in addr;

int port = 8080;

ft_memset( &addr, 0, sizeof(addr));

addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

addr.in_addr.s_addr = htonl(INADDR_ANY); //converts long to a network representation

addr.sin_port = htons(port); //converts a short to a network representation

if (bind(server_fd,(struct sockaddr_in*)&addr, sizeof(addr)) < 0){

write(2, "error\n", sizeof("error\n"));

return (1);

}Before any connection happens the server's gotta have a socket waiting for incoming connections. To achive this we use the listen(); system call

int listen(int socket, int backlog);It calls the socket it should be accepting incoming connections from, thats the first parameter. The second one is the amount of pending connections it can handle before starting to refuse them.

The accept function grabs the first connection request that's pending and creates a new socket for it. The socket that was created by the socket(); system call is just used for accepting connections. The syntax of accept is:

int accept(int socket, struct sockaddr *restrict address, socklen_t *restrict address_len);It's parameters are: socket, the socket that's set for accepting connections with listen();; address, the address thats filled with the client that is trying to connect address; address_len, is the lenght of the structure.

The code would look something like this:

if (listen(server_fd, 3) < 0){

write(2, "error\n", sizeof("error\n"));

exit(1);

}

if ((new_socket = accept(socket_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address, (socklen_t *)&addrlen)) < 0){

write(2, "error\n", sizeof("error\n"));

exit (1);

}Once the connection between the server and the client has been stablished we can start with the info exchange. This part is easier than the previous ones, since we use functions we are all familiar with, read(); && write().

It would look something like this:

#define BUFF_SIZE 1024

...

char *buffer[BUFF_SIZE];

if ((int reader = read(new_socket, buffer, BUFF_SIZE)) < 0){

write(2, "error\n", sizeof("error\n"));

return (1);

}

write(1, buffer, BUFF_SIZE);

char *msg = "Server: Got your request\n";

write(new_socket, msg, strlen(msg));We use the same system call we use when dealing whit FD's: close();

close(new_socket);We've learnt how to setup a simple server that works on TCP we can start writting a simple code that creates and server and waits for a request. If you follow this guide you should be able to test if your server is working by googling 0.0.0.0:8080, or 0.0.0.0:X, X being the port you use, but I'd recommend using the 8080. If you want to see a code doing this jump to /resources/simpleServer/.

Ok, now that we've done the TCP part of the code we should start on the HTTP one.

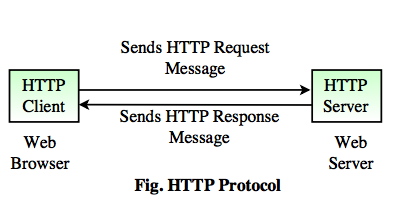

The basics of HTTP communication are that the Client sends an HTTP request to the HTTP server, and then the server processes the request and sends an HTTP response to the HTTPS client.

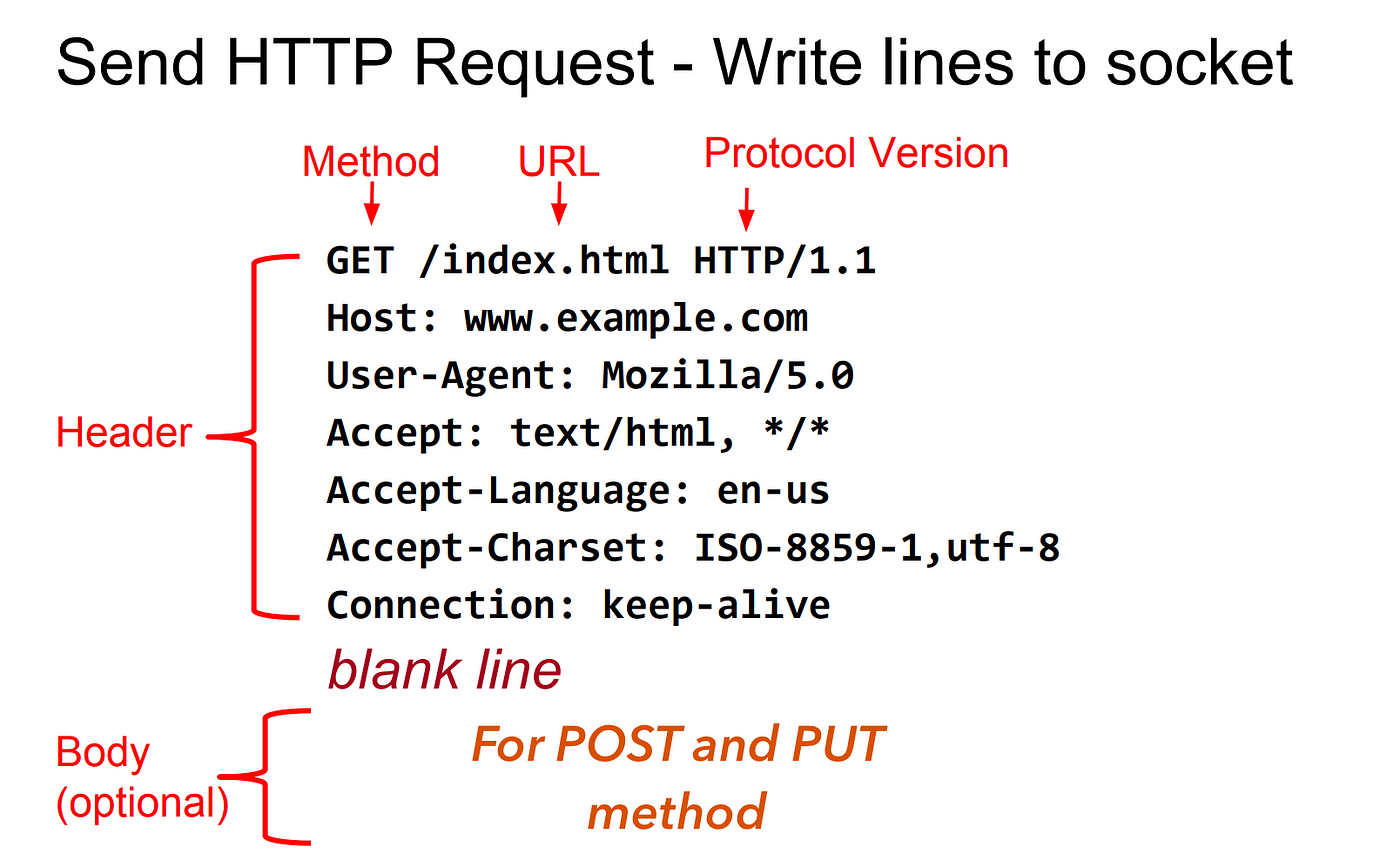

Now we have to see what are they really sending/requesting

The client connects to the server, the server cant connect to the user. So the client is who initiates the connection

http::/www.example.com:8080/index.html

To display the webpage the browser fetches index.html from the webserver. With www.example.com is the same but with the default(port: 80, file index.html, http protocol). So if you were to type in a browser it would come up with something like http://www.example.com:80, so this is what out web browsers send to the internet while we are browsing.

The server can be configured so it has some default settings, like a default page when we visit a folder on the page. The webpage is decided by the name of the file, some servers have index.html others public.html. In this example we'll be using index.html.

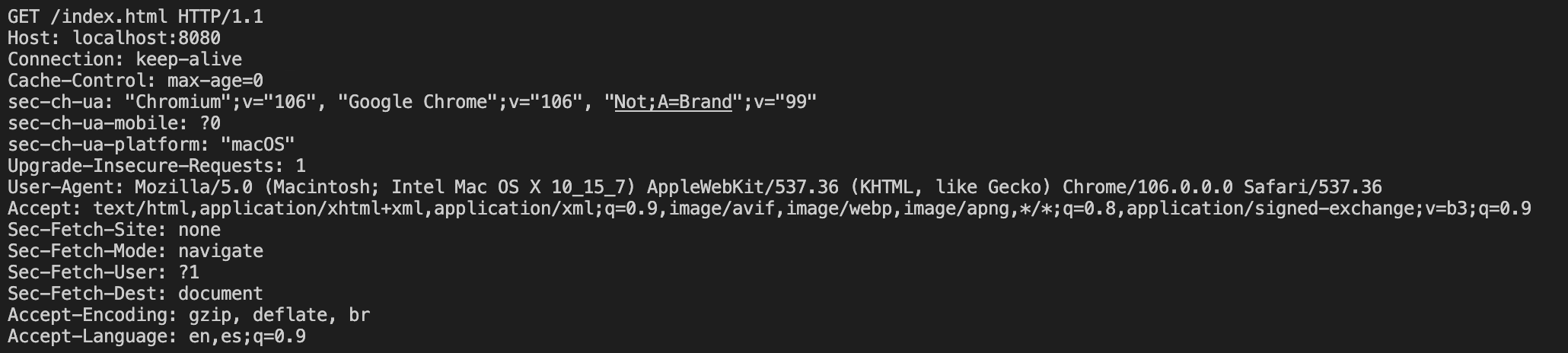

We will be testing this with out little server we just made:

- Run the TCP server

- Type "localhost:8080/index.html" on your browser (instead of localhost you can type 0.0.0.0)

- Now look at the terminal

You should be seeing something like this:

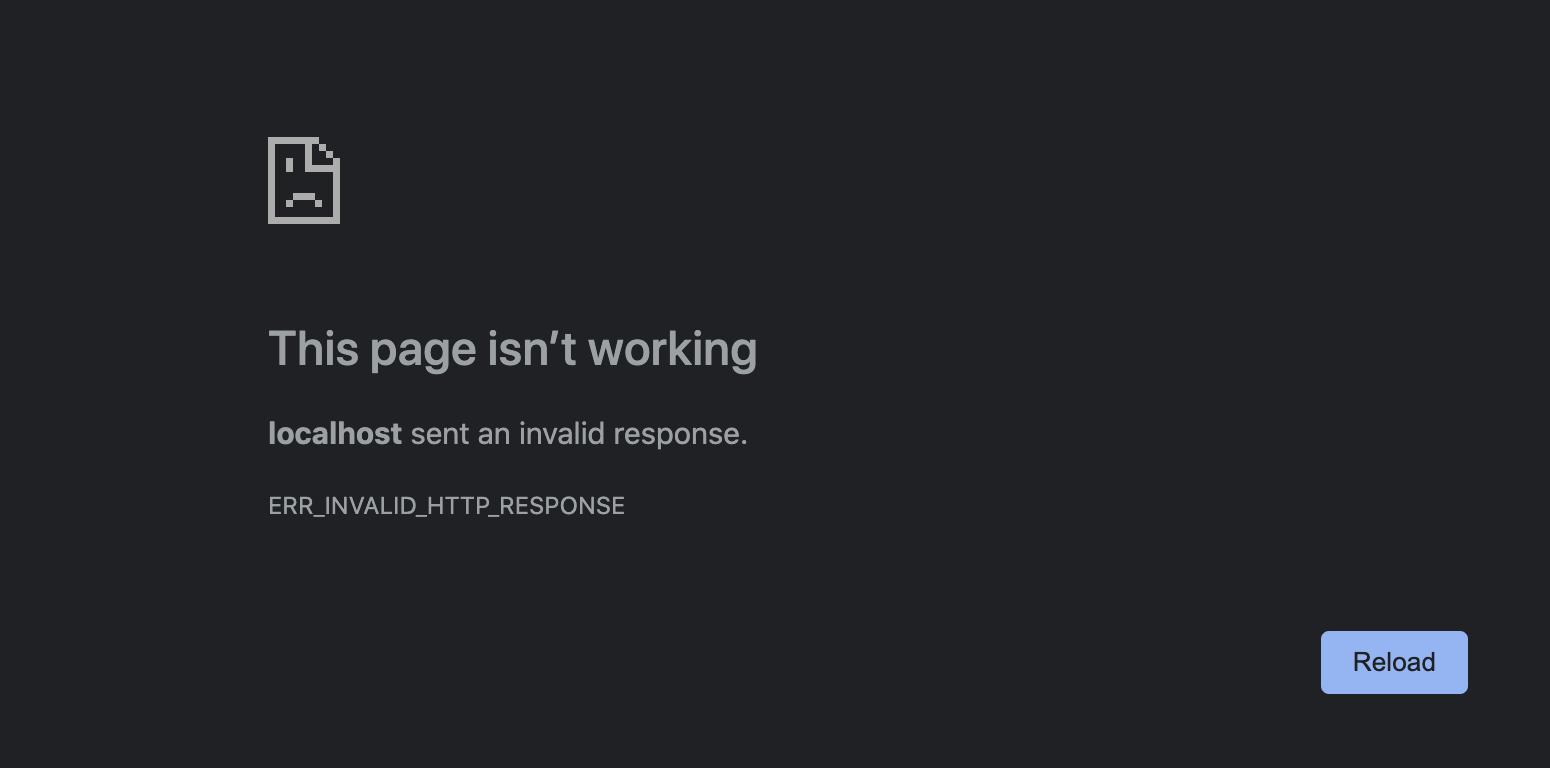

And your browser should be saying something like this:

Obviously, our response was a message that said "Yo, Im the server\n", the browser cannot read that.

GET is the default method use by HTTP, but there are 9 Methods:

| HTTP Methods | Use |

|---|---|

| GET | fetches a URL |

| HEAD | fetches info about URL |

| PUT | Puts a URL |

| POST | Send Data to a URL and get a response back |

| DELETE | Deletes an indicate data |

| CONNECT | Makes a tunel to the server |

| OPTIONS | Describes the communication options for the target |

| TRACE | Performs a message loop-back test along the path to the target resource |

| PATCH | Applies a modification to a resource |

Now It's time to start sending responses to the client. The client sends a header expecting a response from us, but we are just responding whit a simple message, let's change that.

The Client's browser is expecting a response in a certain format.

HTTP is nothing more complex than following the rules specified in the RFC documentation.

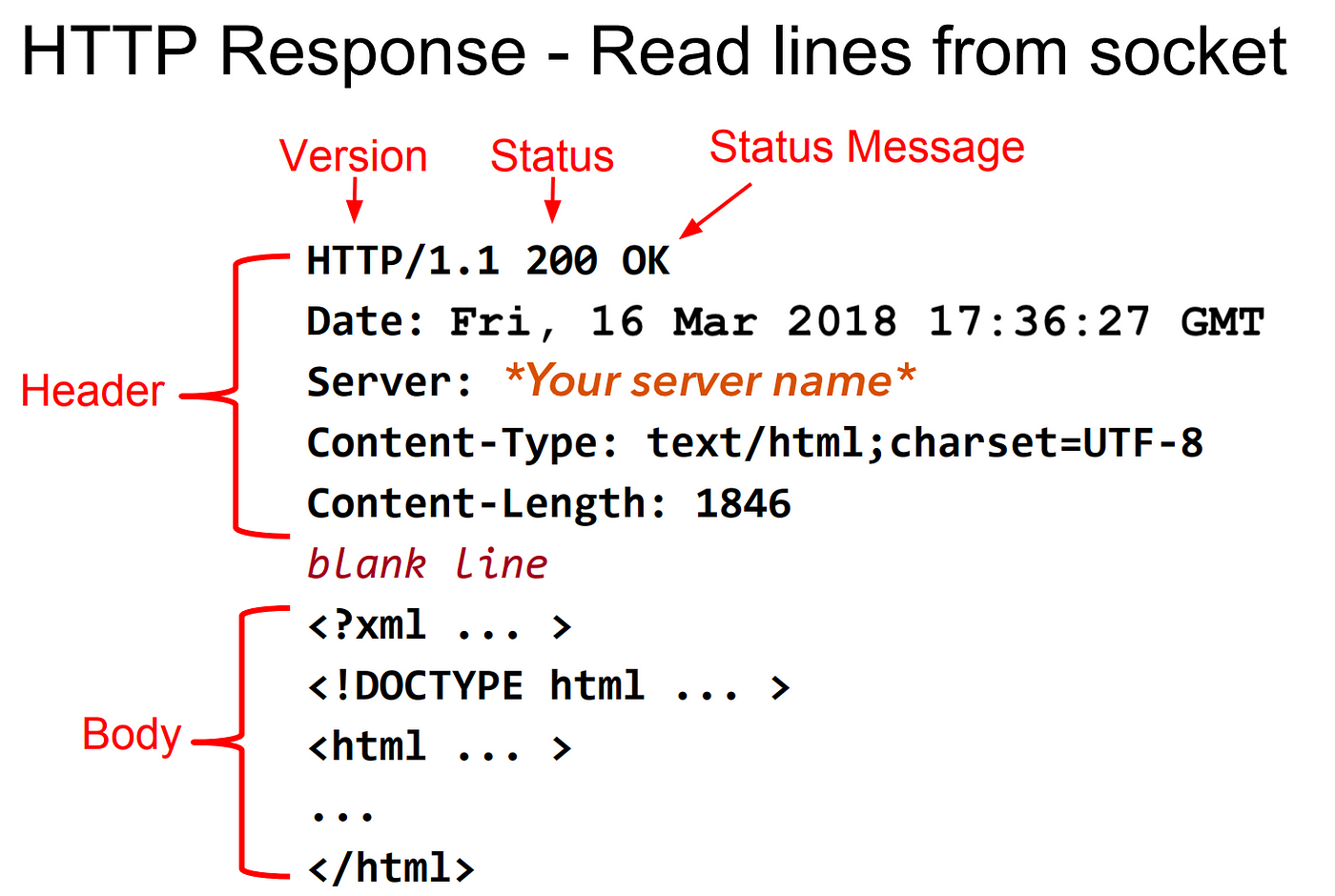

This is the HTTP notations for responses web-browsers expects us to use:

If we want the client to see the response we first need to send the header, then a blank line and then the message you want. The header shown above is just an example of many, if you want to see more you cant take a look at HTTP RFCs.

Now let's construct a simple header so our server client can see something else than an error:

char msg[] = "HTTP/1.1 200 OK\nContent-Type: text/plain\nContent-Length: 12\n\nHello world!"; The 3 minimun headers you've gotta have are these:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK, the HTTP version we are using, the Status Code and the Status messageContent-Type: text/plain, this says that the content we are sending is just plain text. There are many Content-Types, I'd suggest looking at this or thisCode-Lenght: 12, the amount of bytes the server is sending to the client, the web-browser wont read more than those

The next part is the body, we need to calculate how many bytes are we sending for the Code-Lenght: and also set the Code-Type: to the apropiate one.

Status Codes are issued by the server to the client in response of a request. It includes codes from IETF Request For Comments(RFC), other specifications and some aditional codes used in some common aplications of HTTP.

The first digit of the Status Code specifies one of the five standard classes of responses. The message shown have defaults but human readable alternatives can be shown. Unless stated otherwise the status code is part of the HTTP/1.1 standard RFC231.

So, for example, if you can't find the file the client is asking for you send the apropiate status code, if the client is trying to access a file he doesn't have permission to access you send the apropiate status code, and so on...

If we ran the code we previusly wrote and change the char msg[] = "whatever"; to char msg[] = "HTTP/1.1 200 OK\nContent-Type: text/plain\nContent-Length: 12\n\nHello world!";, and then connect to localhost:8080 in you browser you should get something diferent.

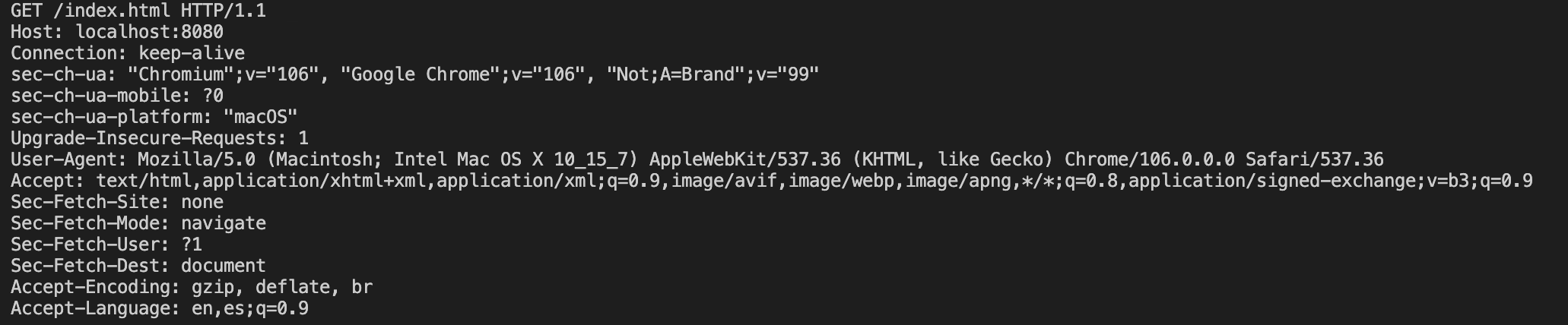

Now that we've sent a message, how do we send another datatypes (images, webpages, ...). Lets suppose we've entered localhost:8080/index.html, we get this in the terminal:

For simplicitys sake we just consider the first line of the request: GET /info.html HTTP/1.1 . All we have to do is look for index.html in root. If we were to enter localhost:8080/srcs/html/index.html we would have to look insede of /srcs/html/ for this. There are so many cases to consider:

- The file is present

- The file is absent

- The client has no permission to see the file

- ...

First we have to select a status code from here, then we select the content-type here, then you open the file, read the data into a variable, count the amount of bytes and set the Content-Lenght, and then construct the respond header. Then you add a newline and append the data from the file we wanted to send. Once this is done the final step is to just send the Header to the client

Huge Shoutout to Skrew Everything for making an easy tutorial to understand HTTP servers

When accepting a request from a server we can use many functions, but those like accept(); or recv(); are blocking. This can be a problem when a server is trying to handle a big amount of clients, where the server would end up blocking a big amount of clients. So the solution to this problem would be using other socket calls, like select(); or poll();, these calls let us handle multiple sockets without blocking none of them.

The easiest way to get around this problem would be making a thread pool, but since we cant use any of the pthread functions we have to use one of the commands used above. The one we'll be using is gonna be select();

Sockets are by definition blocking. If you dont know this you probably havent dealed with sockets too much. Every developer that has worked with sockets has had to learn a way around this.

Why are sockets blocking? Well just as any other function when you call it it enters the fucntions, does it thing and returns a value. If the function is too long it take some time until it returns something. In case of sockets, since their task is to wait for something to read, so it will block until it reads something from the socket. So a socket will hang until data is aviable to be read. In accept();'s case untill the client tries to connect to the server.

- Using the

select();system call

Before using select we have to understand how it works. It takes a number of file descriptors that you want to read from, it checks which of them are ready to be read or wrote and gives them back. So it does not block that way.

The basic way of using it is to initilize the fd_set in a loop, then test all the sockets and then deal with the ones that hold some info to work with.

- Using non-blocking sockets

This would seem to be the easiest way around it. Well sockets are blocking, what if they were not? Sockets have many options and one of them is to make them non-blocking. It seems that easy untill you realize that turning it off makes the dealing with the socket more complicated. I wont elaborate more on this.

- With a thread pool

I'd recommend doing this method, but since the subject I've to stick to doesnt allow me I wont be using it. With this method you make a thread pool of the amount of connections you want your server to be able to handle, and you assing each thread with a socket to stablish the connection on.

Using select makes you learn about new concepts, data types, macros and so on...

Here is the basic problem: if there is a socket holding some data the socket will return it, but if it has nothing in it it'll hold there. Knowing that you cant work with the sockets that have info in them and ignore the rest of them.

This is what select lets us do. We have 3 set_fd, the read, write and exception ones you pass them and it checks wether they are ready to perform their operations.

int select (int nfds, fd_set *read-fds, fd_set *write-fds, fd_set *except-fds, struct timeval *timeout);

int nfds

The highest-numbered file descriptor in any of the three sets, plus 1. The usual thing

is to pass FD_SETSIZE as the value of this argument.

In Winsock, this parameter is ignored; it is included only for compatibility with

Berkeley sockets.

fd_set *read-fds

An optional pointer to a set of sockets to be checked for readability.

fd_set *write-fds

An optional pointer to a set of sockets to be checked for writability

fd_set *except-fds

An optional pointer to a set of sockets to be checked for exceptional conditions.

struct timeval *timeout

The maximum time for select to wait, or NULL for blocking operation.

Return Values

1 or greater -- The total number of sockets that are ready.

zero -- The time limit expired; ie, none of the sockets are ready.

-1 -- An error occurred. In Winsock, this return value will be SOCKET_ERROR.

Use the applicable function to identify the actual error (eg, in Winsock,

call WSAGetLastError()).

We have a new data type, the ft_set. Its a set of file descriptors and as far as it concerns us a set of sockets. We create a set of sockets to let select know where to work. Its also the way select returns the socket we can work with. This obviously tells us that select edits fd_set, therefore each and every time we call select it changes our fd_set we have to re-initialize our fd_set.

These are the macros we are going to use to work with an fd_set:

int FD_SETSIZE

The value of this macro is the maximum number of file descriptors that a fd_set

object can hold information about. On systems with a fixed maximum number, FD_SETSIZE

is at least that number. On some systems, including GNU, there is no absolute limit on

the number of descriptors open, but this macro still has a constant value which controls

the number of bits in an fd_set; if you get a file descriptor with a value as high as

FD_SETSIZE, you cannot put that descriptor into an fd_set.

void FD_ZERO (fd_set *set)

This macro initializes the file descriptor set set to be the empty set.

void FD_SET (int filedes, fd_set *set)

This macro adds filedes to the file descriptor set set.

void FD_CLR (int filedes, fd_set *set)

This macro removes filedes from the file descriptor set set.

int FD_ISSET (int filedes, fd_set *set)

This macro returns a nonzero value (true) if filedes is a member of the file descriptor

set set, and zero (false) otherwise.

So the normal procedure would be to start with FD_ZERO, and then set each socket individualy each socket with FD_SET. The next step would be checking if select return 1 or greater and then you would compare with the returned set through FD_ISSET

The general way of dealing with select(); is to make a loop that periodically calls select. You send select a list of sockets, and when select returns you'll go through each socket seeing if it's ready, the process it and go check the next one.

I'll recommend watching this video, which is how I implemented select into my server. Jacob Sorber's video on select and for further understanding of this I'd go watch this really nice tutorial of a wholesome Scottish dude. The rest if for you to figure out.

Thanks to this guide and also this other guide

To actually start with the section we have to read a little bit about the HTTP Methods on the RFC7231. If we want to Implement HTTP methods to our server we have to first understand what they are, how they work and what are the standards.

The subject says that we have to implement, at least, GET | POST | DELETE. These are the only ones we are gonna work with.

Implementing the Request and Response is not the hardest part to program, but to implement clearly. In our case we've made a routes directory where we store as much .cpp files as routes we have implemented (ex: /index, /index/public, /profile ...). Each file checkes if the route goes deeper or if it stays there, if so it checks if the METHOD request is allowed in that route and fills up the response object and sends it.

If you've implemented everything I've talked about so far you should be able to display a full static .html webpage. The easiest way to implement this last part if by just having one route /index and one METHOD, GET.

Quick Tip:

To implement css, js, images, mp4, mp3... files to your static webpage you just have to reference them correctly on your .html file. In my case I'm using Chrome, while this browser reads the HTML if it finds a reference to a .something file it will send a GET request to the server, so if you have implemented the GET method to the extension file that the browser's just requested you should be able to return it.

-

First Test: the first test of the server is a simple GET request, at this point this shouldn't be an issue.

-

Second test: this one one comes in hard, it is a POST request that has the Transfer-Enconding: chunked header, which we dont know how to deal with right now.

Id look at this two sections of the RFC 9112:HTTP/1.1 Section 6 and Section 7.1. You also have this exmaple on stackoverflow

- An overview of HTTP

- Some HTTP things(ESP)

- MND WEB DOCS select function

- HTTP Server: Everything you need to know to Build a simple HTTP server from scratch

- What is a .tpp file (ESP)

- What is a .ipp file (ESP)

- stack overflow AF_INET

- stack overflow SOCK_STREAM

- struct sockaddr_in

- socket programming: socket select

- socket programming: introduction

- more info about socket, another tutorial

- an old tutorial (<2010) about sockets

- Dealing With and Getting Around Blocking Sockets

- Wipedia About Berkeley Sockets

- Wikipedia On HTTP Headers

I Do not belive in those things