- Adaptavist Word Count Assessment Notes

.

├── img

│ ├── adptv-logo.png

│ └── jacoco-ss.png

├── pom.xml

├── README.md

└── src

├── main

│ └── java

│ └── wordcount

│ ├── App.java

│ └── textprocessor

│ └── TextStatistics.java

└── test

├── java

│ └── wordcount

│ └── AppTest.java

└── resources

├── adaptavist.txt

├── empty-file.txt

├── gutenberg.txt

├── stockexample.txt

└── unicode.txt

10 directories, 12 files

This is a Maven project so requires maven to build and run.

- First clone and enter the root source code directory.

git clone https://github.com/ArenT1981/advst-word-count

cd advst-word-count- Next, compile/build the code

mvn clean compile. - Next, run the tests and generate the

jacocotest coverage binary stub:- i)

mvn testto run the tests; - ii) Followed by

mvn jacoco:reportto generate the HTML report.

- i)

- To inspect the code coverage report, open the generated

index.htmlusing your web-browser, undertarget/site/jacoco/index.html. e.g.

xdg-open ./target/site/jacoco/index.html on Linux/Unix/POSIX systems.

- To run the application on the supplied demonstration files, simply run it without any arguments:

mvn exec:java -Dexec.mainClass="wordcount.App"

- To run it on plain text file(s) of your choice, supply it/them as space delimited arguments with the path/file location. You can specify multiple files/arguments:

mvn exec:java -Dexec.mainClass="wordcount.App"- Dexec.args="path/to/file1.txt path/to/file2.txt path/to/file3.txt"

The file src/test/java/wordcount/AppTest.java contains a sequence of JUnit that tests that provide close to 100% code coverage on the target classes. These exercise the code using some example/demo files which are present under src/test/resources and cover a gamut of demonstration/use cases. Inspection of this class should provide a pretty good specification as to how the code works/behaves. It is worth noting that the code works just fine across unicode files, though the merit/benefit of being able to treat emojis, etc., as "words" is of course debatable.

It gracefully handles empty files or non-existent files.

This file is not particularly interesting, other than that it handles the passed in command line parameters, or otherwise runs a "demo". The demo makes use of some supplied text files to exercise the code, and show the usage of the TextStatistics.java object, via a small void runDemo() method.

This is where the bulk of the work is done. The object/class is deliberately named with the more general appellation TextStatistics, highlighting that in principle, one could conceive of many other further/future "statistics" operations one could perform on a text file for whatever purposes. Similarly, one could reasonably also envisage titling it TextAnalysis for that matter.

This method uses a "try-with-resources" structure to ensure we don't have any dangling file pointers/handles left open once the input file has been processed. It's purpose is simply to read in the file, line by line, and use a StringBuilder to assemble it into one String. There are a couple of hard-coded constants/limits (line length and file length) that have been set at reasonable defaults to ensure that one does not attempt to read in files of ridiculous size. Obviously if extremely large file handling was a requirement, that would probably necessitate a much more complex solution that the one presented here, if the objective was to minimise RAM overhead.

This method then runs the parsed file through ParseText which delivers the data structure with the word counts in (see below).

This method uses a StringTokenizer (one could equally well use the in-built string split() method) to split the input string into words/"tokens". Necessarily, it is "opinionated" (see Caveats/Deliberate Requirements Assumptions below), so in this case treats hyphenated compound words as one "word", similarly with forward slash separated alternative terms (e.g. "someday/maybe" is treated as one word). It employs the POSIX "punctuation" class within a regular expression to remove quotation and other surrounding particles. All words/tokens are taken in their lower case form, since we are interested in their "token count" rather than their grammatical representation; i.e. we don't care about title case.

The pairing/tuple of (<word>, <count>) is stored in a LinkedHashMap <String, Integer> since this structure is efficient for iterating over in a given sequence, whilst retaining the desirable attributes of a key/value pair (e.g. "tell me how many times the word adaptavist appears in the given text").

The actual computationally intensive sorting task is performed by the sortWordCounts() method (see below).

This method uses a compact but involved Java 8+ style streams/functional approach to sort the word counts into descending order (i.e. largest count first). The Map.Entry.comparingByValue inbuilt when combined with the Comparator.reverseOrder() achieves just what we are after; meanwhile an anonymous lambda then builds the new resultant LinkedHashMap as part of the collect() method to return the sorted map, which we can now iterate over in the manner of a list.

This is just a convenience wrapper used by our parseTextFromFile method as part of its try-with-resources.

A public accessor method to return access our private sortedCounts LinkedHashMap data structure.

Here we @Override the inbuilt toString() method so we can very easily dump the sorted word maps/list to console by simply calling System.out.println() on an instance of aTextStatistics object.

Obviously this task is not presented with a formal requirements specification that adumbrates every or indeed even any behavioural/performance/data characteristics of the desired solution. In the absence of such a specification, then, it falls upon the software engineer to state, within reasonable limits, what design assumptions they made when producing the solution. Here are mine:

- The solution does not need to be, or care about, being "thread safe", since we're not attempting to make some type of multi-threaded or massively distributed solution.

- The solution does not to deal with, or care about, particularly huge files, where this naive approach would exhaust a system's memory or have otherwise unacceptable performance characteristics. Apparently there is a large pirated eBook library (i.e. epub files) floating around the internet that is approximately 3.8TB big. One could imagine if one wanted to devise some kind of word counting/textual analysis solution for that, something more elaborate than what is here would probably be required or desired. Once again, however, it would really depend on the intended outcome/use-case. Even if a solution was relatively "slow", if it is something that is only run as a batch-script overnight once, why over-engineer something if the simple solution would suffice? Here, the Agile principle of "make it good enough" is always pertinent, as is the apocryphal "worse is better" principle.

- More problematical than performance for this software task, is the fact that there are an enormous number of edge-cases that would require a vast amount of additional complexity to solve, together with their stated methodology/intended behaviour when encountering them. In particular, consider "their / they're / there" - are these three separate words, or not? One could imagine considering etymology/philology/word stems when counting words. Dealing with apostrophe's, both as an English grammatical construct but also as a speech or quotation indicator is another consideration. There is the matter of dealing with the innumerable other "extra linguistic"/syntactical operators; for example, bullet points, asterixes, footnote symbols, etc. The point is, the limitations of the solution here would obviously become apparent if one were to throw it against a full corpus of real-world texts, where the peculiarities/difficulties of designing and building a general purpose parser that dealt with them all nicely would be decidedly non-trivial. Here, we are into matters that would require a detailed contextual understanding of the use-case rather than simply an intrinsic property of the code/solution. To illuminate what I mean, consider the very real-world concern of compiling/assembling datasets for machine learning systems. Here, one of the most time-consuming parts of the entire software life-cycle is the necessary "data-cleansing" and appropriate formatting, in a standardised manner, for consumption/ingestion by the given system such that the dataset is not "polluted" with artefacts. I have read anecdotal reports where as much as 90% of the total time spent producing the given system in such areas has been spent on carefully cleaning and curating the initial training dataset (often necessitating a lot of very labour intensive and painstaking manual editing). A similar issue would be true for our word count or general "text statistics" program under consideration here, if we were, as an imaginative exercise, to consider it applied in a wider real-world context; one could either invest enormous effort into supporting or dealing with as many edge-cases/"dirty" input texts as possible, or one could instead keep the code simpler but make assumptions on the cleanliness of the input, thus shifting the onus of work into the preparation of suitable input files. In any case, two small explicit assumptions were made here; hyphenated words are treated as one, as are forward slash separated terms, without additional spacing. The more general point I am making is that the limitations of the parser are known, and no attempt has been made to make it significantly "cleverer", since to do so would soon exceed the reasonable scope of the task/time invested set here, not to mention it would depend on the intended purpose of such software in a wider context. Yet this is an isolated technical task for demonstration purposes.

- Whilst the solution does require reasonably sane input files in order to deliver decent results, it nevertheless does cope nicely with empty files, and has deliberate protections in place against unreasonably large files. Having some degree of explicitly hard-coded rather than parameterised values is a reasonable design trade-off. It should also happily ingest any platform readable plain text files, including unicode. Further testing would be needed to establish whether additional protections/additional code to check and verify strange character sets or file encodings on other platforms would be needed. Once again, the object was not to over-complicate matters and turn this into too lengthy a task.

- One final matter to consider: this solution does not work at all for certain languages. In the West, we tend to always assume that the words/token of a given language are separated by spaces. A cursory inspection, of, for example, the Thai language, shows that this assumption is not at all universal. So this solution would not work at all on a Thai input text, as it would be likely to consider the entire paragraph of text as one "word", since Thai language does not depend on or use spaces to separate individual words. The same observation/limitation, or variant thereof, also no doubt applies to a multitude of other non-English languages.

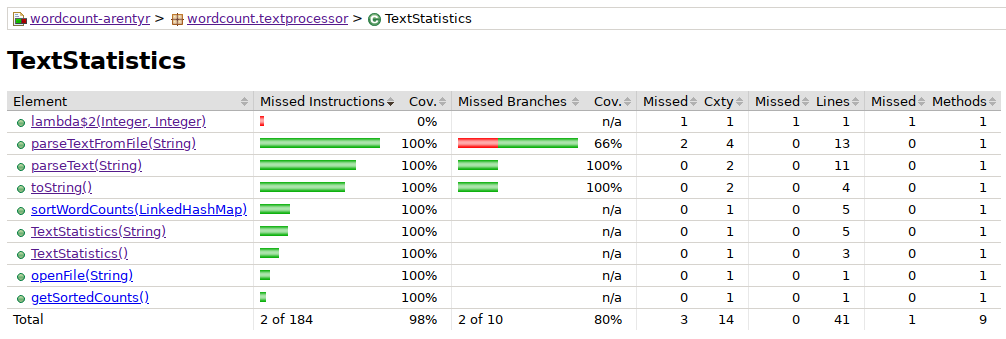

Within the constraints discussed above, this solution employs a reasonably substantial test class/cases, together with the use of the Jacoco code coverage library that provides the nicely formatted code coverage report that you can view using a web-browser (generated under target/site/jacoco). As you can see, the test code provides coverage across virtually the entire code-base.