This repository contains three projects that explore the idea of calling Swift code from CLR languages (in this case, C#) via the relatively new C++ interop feature of Swift.

Note: You can find a less technical writeup of this project in my blog post Proof of Concept Project: Combining Swift and C# on Windows with SwiftToCLR.

Here at Cascable, we have a product called CascableCore, which is an SDK for connecting to and working with over 200 cameras from multiple manufacturers. This SDK powers our own consumer-facing products, as well as those of a number of other developers who license our SDK for their apps.

Currently, CascableCore only works on Apple platforms. However, we'd eventually like to bring it to other platforms so we can expand our offerings, and on Windows this should mean that apps written with modern languages and tooling (i.e., C#) can easily use the SDK.

This proof-of-concept explores the idea of using a pure-Swift codebase to achieve this, bridged into C# via C++.

With newer Swift versions, you can enable C++ interoperability with a build flag, and another to generate a C++ header.

Since we can call into C++/CLI from C#, this should be a piece of cake!

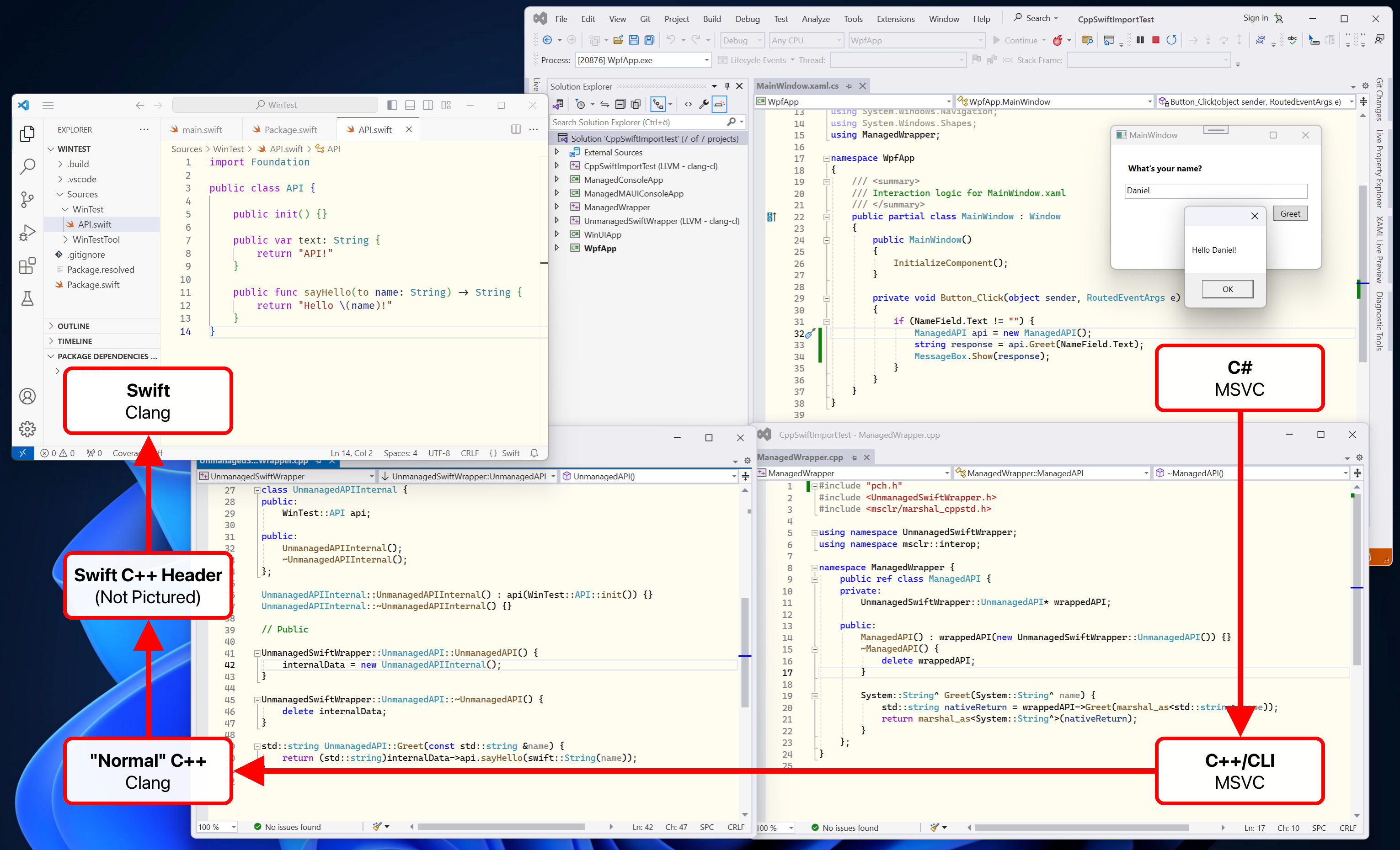

When you start to explore this idea, however, it quickly becomes apparent that it's not going to be as simple as it seems. The relevant facts are these:

-

The Swift compiler,

Clang, generates an API header that I can only describe as "5000 lines of chaos" for the simplest of Swift APIs. This header can, as far as I can make out, only be parsed byClangitself, and not the Microsoft C++ compiler (MSVC). -

The ABI, however, is standard C++.

-

In order to be called from CLR (i.e., the garbage-collected runtime environment C# code runs in), we need to use a variant of C++ called C++/CLI.

Clangcan't generate C++/CLI, butMSVCcan.

This means we need not one, but two C++ wrappers.

-

A 'simplification' wrapper, compiled by

Clang, that takes the Swift interop header and re-defines it using a, er, "normal" C++ header thatMSVCcan understand. -

A 'CLRification' wrapper, compiled by

MSVC, that takes the simplified header and redefines it in C++/CLI that can be called from within the CLR and from C++.

An early, simple example of this that I put together a couple of months ago looked like this:

This process isn't particularly difficult, but it sure is tedious! CascableCore's API surface is pretty big - approaching 50 protocols and hundreds of methods, properties, and enum cases. It is relatively static — we don't like to break our customer's builds if we can help it — so in theory once we've gone through the pain of building these two wrapper layers, it'll be a relatively small maintenance overhead going forward.

However, that's no fun! And, what if you're building new code and want to prototype it via a C# app as you're iterating? Having to rebuild each change you make through two wrapper layers would be like wading through treacle!

This is a job for automated code generation, and that's the meat of this proof-of-concept: a command-line tool, written in Swift, called SwiftToCLR.

SwiftToCLR takes the C++ interop header produced by the Swift compiler and uses LibClang to parse it and create both wrapper layers needed to get into the CLR.

There are multiple projects in this repository, which together provide an end-to-end implementation of the task at hand for you to experiment with:

The Swift Project folder contains the Swift project we want to use from C#. I wanted to use "real" code, so that's what I've done:

-

The

CascableCoretarget contains a Swift redefinition of the CascableCore API, which is currently a set of Objective-C headers. This is a relatively "straight" redefinition in that it makes no attempt to use any features unique to Swift. -

The

StopKittarget contains a port of our StopKit SDK, which CascableCore depends on. -

The

CascableCore Simulated Cameratarget contains a mostly intact copy of our Simulated Camera plugin for CascableCore. You'll see some clumsily commented-out and rebuilt sections to make it compile on Windows, but it's largely identical to our shipping plugin.

Together, these targets give us a "real" SDK to work with without the complexity to connecting to a real camera via the network or USB, which is outside of the scope of this proof-of-concept.

Additionally, there's a fourth target:

- The

CascableCore Basic APItarget contains a simplified API that avoids the limitations of Swift's C++ interop (see below). It's a very basic wrapper around theCascableCoreAPI, and this is what we're using from our C# demo project.

The SwiftToCLR folder contains the SwiftToCLR tool itself.

The Windows CascableCore Demo Project contains a Visual Studio solution containing three projects:

-

The

UnmanagedCascableCoreBasicAPIproject compiles the "first" wrapper layer from SwiftToCLR usingClang. -

The

ManagedCascableCoreBasicAPIproject compiles the "second" wrapper layer from SwiftToCLR usingMSVC. -

The

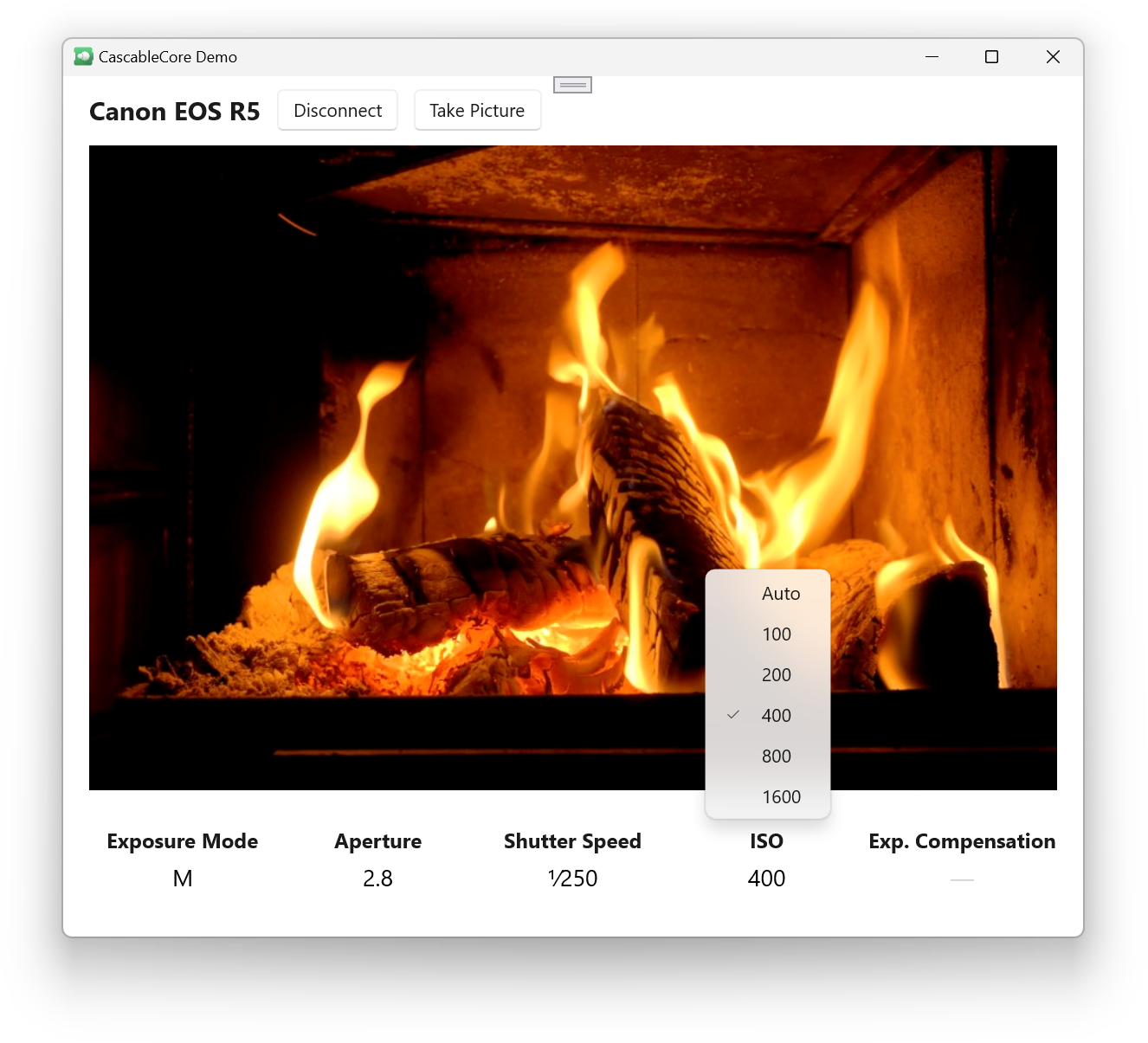

CascableCore Demoproject is a C# demo application that lets you connect to a camera, see the live view stream, and adjust some camera settings. A screenshot of this is what's at the top of this README.

The Mac CascableCore Demo Project folder contains an Xcode project implementing the same app as the Windows demo project, but on macOS using SwiftUI. It's just here to provide a fun comparison on how you might build the same app in C# on Windows and in SwiftUI on the Mac.

Note: Each project in this repo is standalone, so if you want to just fire up the demo project and look around you don't need to build the Swift project then run SwiftToCLR on it (although you can if you want!). However, for the Visual Studio solution you will need to edit the Directory.Build.props file to point Visual Studio to your local Swift installation. For more details, see the "Technical Notes: Windows Demo Project" section below.

If you want to see the "journey" of a Swift API into C# without having to fiddle around with the repo, you can check out:

-

CascableCoreBasicAPI.swift contains the definition and implementation of the Swift API that we want to call from C#.

-

CascableCoreBasicAPI-Swift.h is the Swift C++ interop header for our Swift module, and it's what you'd give to SwiftToCLR. Warning: It's nearly 8,000 lines — the actual API definition is near the bottom.

-

UnmanagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.hpp is SwiftToCLR's output for the first wrapper (wrapping the Swift C++ header in "normal" C++). The implementation is in UnmanagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.cpp.

-

ManagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.hpp is SwiftToCLR's output for the second wrapper (wrapping the "normal" C++ header in C++/CLI). The implementation is in ManagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.cpp.

-

There's no C# definition of the API since .NET automatically exposes C++/CLI symbols to C# with no additional steps required.

Note: SwiftToCLR will compile and work on macOS as well as Windows (although it requires Xcode to build on macOS - see the SwiftToCLR technical notes section below). The examples here are for Windows.

SwiftToCLR has a simple command-line interface. Once you've compiled your Swift target and have a C++ header file for it, give it to SwiftToCLR along with your target's module name, a path to Swift's swiftToCxx header directory (which contains supporting headers for Swift's C++ interop), and an output directory.

.\SwiftToCLR.exe CascableCoreBasicAPI-Swift.h

--input-module CascableCoreBasicAPI

--cxx-interop .\swiftToCxx

--output-directory .

SwiftToCLR will parse your Swift module and output an "unmanaged" wrapper and a "managed" one:

C:\> .\SwiftToCLR.exe ...

Using clang version: compnerd.org clang version 17.0.6

Successfully wrote UnmanagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.hpp

Successfully wrote UnmanagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.cpp

Successfully wrote ManagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.hpp

Successfully wrote ManagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.cpp

C:\>

There are a number of additional options and commands to customise SwiftToCLR's behaviour and wrapper names. To view the documentation, run .\SwiftToCLR.exe --help.

Once you have your header files, you need to make a couple of Visual Studio projects to compile them.

-

The "unmanaged" wrapper should be built with the

LLVMtoolchain and link against the.libfiles the Swift compiler output, as well as theswiftCore.libbinary inside Swift's distribution. -

The "managed" wrapper should be built with the Visual Studio toolchain, link against the same

.libfiles as the "unmanaged" wrapper project as well as the.objbuild result of the unmanaged wrapper, and use the appropriate flag to compile using C++/CLI (such as/clr:netcore). -

The app consuming all of this should depend on the managed wrapper, and all

.dllfiles produced so far (from both Swift and the wrappers) should be placed in the app's build directory.

For an example of all this, see the Windows Demo Project included in this repository. See below for important compiling instructions.

All of the source code in this repo is licensed under the MIT open-source license. However, the Cascable and CascableCore logos and graphics used in the demo projects are not included in this license — they remain the exclusive intellectual property of Cascable AB and cannot be reproduced or re-used without the express permission of Cascable AB.

Swift's C++ interop is an evolving feature. The Swift "source" project and SwiftToCLR both compile on both macOS and Windows, but you may find limited results with Swift 5.9 and 5.10 that're included in current Xcode versions.

I've been using recent Swift development builds (at the time of writing, a build from late January 2024) for this project. You can find trunk development builds on the Swift.org downloads page. Windows builds can lag behind a little bit at times, but The Browser Company maintains a GitHub repo containing automated Windows builds that's updated very frequently.

The Swift project itself (i.e., the CascableCore, StopKit, and CascableCore Simulated Camera targets) aren't anything particularly special. However, when generating a C++ interop header for them, a number of limitations of Swift's C++ interop immediately make themselves known. At the time of writing (early February 2024), our sample codebase exposes the following:

-

Protocols aren't exposed to C++. This includes basics like

Equatable, which means that implementingEquatableon a type in Swift doesn't get you anoperator==in the C++ header. -

static letproperties aren't exposed to C++. -

Enum cases with more than one associated value will cause the entire enum to be not exposed to C++.

-

Closures/callbacks aren't exposed to C++.

-

If a type isn't available, any methods/properties referencing that type will be silently omitted from the C++ header.

-

This includes Swift's

Datatype, which doesn't have a C++ implementation. -

This includes types from other targets within the package you're compiling. I wanted that

CascableCore Simulated Cameratarget to use thePropertyIdentifiertype fromCascableCore, for example, but that didn't work.

-

Additionally, I observed the following behaviours that I consider bugs:

- Public properties with private setters (i.e., something like

public private(set) var myCoolProperty: String) will have both a getter and a setter in the C++ interop header.

For our sample project, most of these limitations can be worked around. The lack of protocols is disappointing and quite a big one considering our API surface is defined almost entirely in protocols, but we can redefine them as classes without too much trouble.

The lack of Data in C++ can also be worked around simply enough. CLR languages support allocating unmanaged memory, and we can implement something like the following in Swift:

public var rawImageDataLength: Int {

return imageData.count

}

public func copyPixelData(into pointer: UnsafeMutablePointer<UInt8>) {

imageData.copyBytes(to: pointer, count: rawImageDataLength)

}This will be exposed like this in C++:

int getRawImageDataLength();

void copyPixelData(uint8_t* pointer);Finally, up in C#, we can get the data contents by allocating some memory and punching the pointer right through our wrapper layers. This is currently a double-copy, but I'm sure that can be improved:

private unsafe byte[] extractImage(BasicCameraInitiatedTransferResult result)

{

int byteCount = result.getRawImageDataLength();

byte[] destination = new byte[byteCount];

IntPtr buffer = Marshal.AllocHGlobal(byteCount);

result.copyPixelData((byte*)buffer.ToPointer());

Marshal.Copy(buffer, destination, 0, byteCount);

Marshal.FreeHGlobal(buffer);

return destination;

}The biggest problem these limitations impose on this project is the lack of closures. CascableCore relies heavily on closures, since working with cameras (and, well, external hardware in general) is asynchronous by nature. We use closures to observe changes to camera settings, receive live view frames, to know if a command succeeded or not, so know when files have been added to the camera's memory card, and so on and so on.

There are workarounds for this that fall back to C-style function pointers (you can see an example here), but doing that for the multitude of closure signatures we have was out of bounds for this proof-of-concept.

In the end, I settled on making a fourth target - CascableCore Basic API - that defines a simplified set of APIs with the C++ interop's limitations in mind. It's a basic wrapper around CascableCore types, with the following simplifications:

-

Types that were previously protocols are now classes.

-

All needed types are consolidated into that one target so the C++ interop header can contain them all.

-

There are no closures to be found.

This, unfortunately, means that to observe changes we need to poll for them. In the C# demo project you'll find two classes - PollingAwaiter and PollingObserver - that put this behind an abstraction so the rest of the demo can use events and observation is it should. This won't survive a production codebase, but it'll do for now.

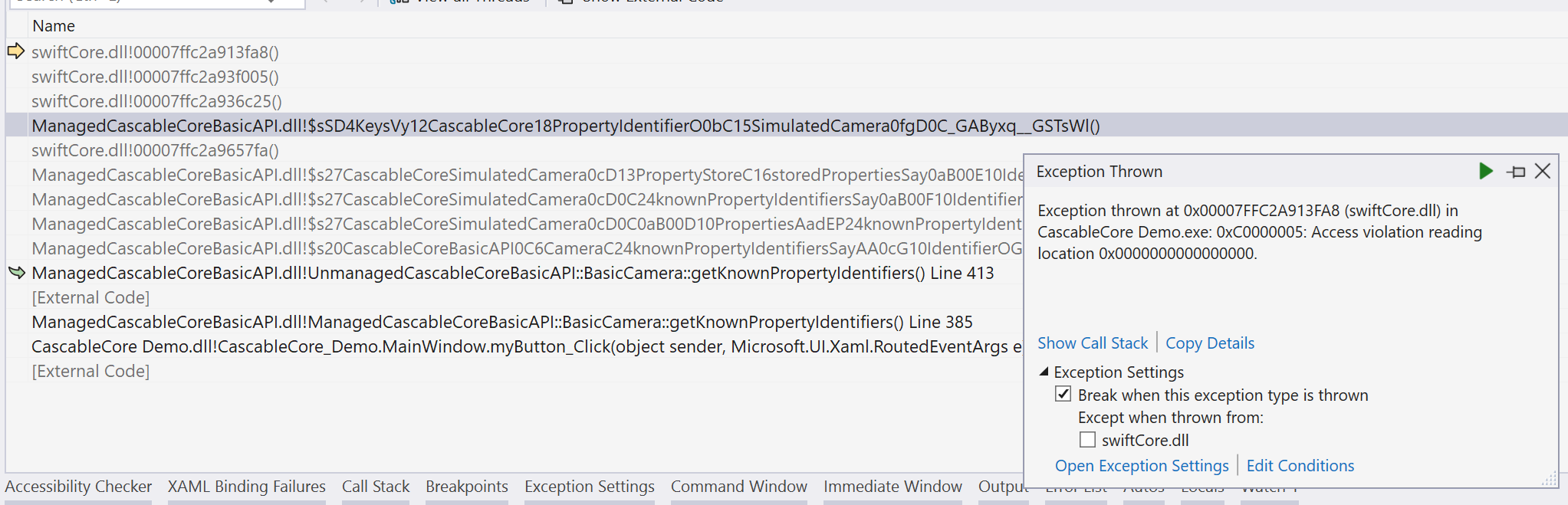

By default, Swift Package Manager will compile library targets statically, which on Windows will give you a pile of .o files - one for each .swift file compiled and an additional one per module. While managing these is a bit tedious, Visual Studio can link to them and ostensibly work fine. If you look through this repo's history, you'll see I was doing that for a good while.

However, I started to experience very odd behaviour. The first was that when accessing dictionary types in Swift code called from C++/C#, the app would crash with a bad access error as if the dictionary was nil. The exact same code running via swift test etc worked just fine.

I eventually found a workaround that confused the heck out of me, complained about it on Mastodon, and moved on. The next day I started getting some other super weird crash deep in swiftCore.dll.

Later, I figured out how to make the Swift Package Manager compile the library targets as dynamically-linked .dll binaries (pro tip: You need to set all involved targets to type: .dynamic, not just the "parent" one) and *poof* - the weird issues went away and I could revert my weird workaround.

It's beyond my understanding to know why this happened or why static vs. dynamic linking is important here, but I was certainly happy to get the problem gone.

SwiftToCLR uses LibClang to parse the Swift C++ interop header. LibClang is included in Xcode on macOS and in the Swift distribution on Windows, and the package should be able to autodetect its location (on Windows, this requires that Swift is installed in a "standard" location).

Note: Running swift build on macOS will fail with an error about an unknown linker flag. The package compiles correctly in Xcode.

Do note that this is very much a pre-alpha quality experiment, and the code should be evaluated with that in mind.

In addition, there are the following known limitations:

-

Support for "container" types is pretty limited. It supports optional types, optional arrays (i.e.,

[Type]?), but arrays of optional types ([Type?]) or optional arrays of optional types ([Type?]?) won't be dealt with correctly. -

Our API doesn't expose any dictionary types, so support for those wasn't implemented.

-

LibClangseems to have trouble handling container types declared by Swift (such asswift::Array,swift::Optional, etc), so SwiftToCLR falls back to string parsing for these types. I've noted this as a red flag in the code - hopefully it's user error on my part.

A side effect of the amount of wrapping we need to do here is that some types need to be copied or adapted multiple times on the way through.

For example, to pass a C# string to Swift and get one back as a return value, we go from System::String to std::string to swift::String and back again, which is most likely to be multiple copies in each direction. This is especially compounded when dealing with arrays, since we also need to translate the arrays from System::Collections::Generic::List to std::vector to swift::Array.

At the moment, this project makes no attempt to work around this, and I haven't even measured the performance impact - it's noted here as a potential future problem.

As noted above, thanks to the CLR's ability to work with unmanaged memory, we can "punch" a pointer straight through from C# to Swift, avoiding forced copies by the wrapping layers.

The demo project requires a modern version of Visual Studio (Community edition is fine) with the Clang toolchain installed. I've been building this project on Windows 11 with a recent Swift development build installed - earlier versions are untested.

The project won't build out-of-the-box due to a hard-coded path to the Swift runtime, which is needed by the linker.

To build the project, edit the Directory.Build.props file alongside the Visual Studio solution, and edit two of the keys:

-

SwiftInstallVersion: Enter the installed Swift version. If you're running a development trunk build (i.e., not a stable release), this will be0.0.0. -

SwiftInstallRoot: The path to the root Swift installation directory. Newer builds want to install into the user home directory, hence the need for everyone to have an adjusted path.

Once these two values have been adjusted, you can build the CascableCore Demo project within the solution and off you go. If you get linker errors, double-check your values above.

While development of this project will slow down as I return to other tasks, my plan is to keep it current with Swift developments and to improve it as time goes on. If you find this project interesting and would like to contribute, please do so - there's even a handy list of immediate improvements that could be made right below.

You're also welcome to chat on Mastodon - I'd be happy to hear your thoughts, particularly if you have more experience with this sort of tooling than I do!

-

Header-To-DLL: SwiftToCLR is a very useful little tool, but you still need to manually assemble the generated header files into multiple Visual Studio projects. It'd be really neat to automate the process end-to-end, so that one command could take a Swift C++ interop header file and spit out compiled

.dllbinaries that you can add directly to the consuming C# app. With the right CMake magic, I'm sure this wouldn't be too much of a challenge. -

Better Handling Of Container Types: As noted above, SwiftToCLR is missing support for dictionaries, as well as various permutations of nested optionals. It should do better.

-

Properties: C++/CLI supports property declarations in a similar way to Swift, and it'd be a nice quality-of-life feature to detect

int getFoo()andvoid setFoo(int value)methods and convert them into properties instead. -

Output Cleanup: I'll be the first to say that C++ is not my strong suit (quite the opposite - I consider my C++ abilities as "bad"), and I'm sure the C++ output of SwiftToCLR could be improved.

-

Code Cleanup: SwiftToCLR has been built in a timeboxed proof-of-concept project. The code is messy at best, and could be significantly improved to be more reliable and more easily understood.

The largest limitation to overcome, for our needs at least, is the lack of closures via Swift's C++ interop. Since we're already generating code, it's not outside the bounds of possibility that a tool could be built to parse the Swift code, pull out public closure definitions, and built out the relevant Swift and C++ code to wrap these in C-style function pointers and definitions.

With the above said, it would be nice to not have to work around these limitations. The Swift C++ interop is (hopefully) still being built upon, and we're not in a giant rush to ship a Windows version of CascableCore. Fingers crossed, by the time that comes around, the interop will be more fleshed out.

While the state of the Swift/C++ Interop feature prevents us from immediately diving in and shipping a Windows version of the full CascableCore SDK, this was a very useful learning experience - albeit a frustrating one at times.

A combination of inexperience with the Windows platform, tooling trouble, and inexperience with C++ turned this "two weeks, tops" project into one that took over a month. However, once everything came together, progress was made remarkably quickly, and I have to admit to experiencing a huge amount of joy when I first saw that fireplace live view stream flickering away in the C# app.

What this investigation has done is given me a lot more confidence in the viability of Swift on Windows. I came into this sceptical at best, but now I can actually see a path to a shipping product.

Our codebase has a lot of Objective-C in it, and a lot of Swift that depends on Objective-C features, so it's going to be a long road.

I'd like to thank a couple of folks who've been particularly inspiring and helpful for this project. They've helped me navigate a tricky and unbeaten path, for which I'm very grateful:

-

Michael Thomas: This whole thing started when I saw a post of his on Mastodon that pulled a thread in my mind that cost me a new laptop and over a month of my life. I do love the laptop, though, and this project has been a ton of fun.

-

Brian Michel works at The Browser Company, and is part of a team building a whole web browser in Swift on Windows! Their approach is different to this one, but equally as interesting. You can see some examples of their work on the GitHub.