- Mean Reversion Strategies

- Background Information

- Stationarity and Mean Reversion

- Augmented Dicky Fuller Test

- Hurst Exponent & Variance Ratio Test

- Cointegration and Pair Trading with Mean Reversion

- Determining the Hedge Ratio - Linear Combination

- Cointegrated Augmented Dicky Fuller Test

- Linear Regression

- Linear Regression with Moving Window

- Kalman Filter (Advanced)

- Johansen Test (Advanced)

- Generating Entry and Exit Signals

- Half-Life of Mean Reversion

- Standard Deviation

- Standard Deviation - Linear Scaling

- Standard Deviation - Bollinger Bands

- Testing with BackTrader

- Where do you come in?

Here I test out some of the mean reversion strategies found in algorithmic trading textbooks to see how well they work in practice (aka how well I can execute them... lol). The Strategies here were read about in Algorithmic Trading by Ernest P. Chan - a great book but hard to follow at times. The initial rough work and visualization of the strategy will be in jupyter notebook, then we will do a proper backtest in Backtrader (Python backtesting library)

To understand the demo strategies I will present, let us go over some of the core mathematical principles that the algorithms will use. We will use examples from the strategies themselves to illustrate the concepts and by the end, you will be able to piece together a mean-reverting strategy from scratch.

The core concept governing mean reversion strategies is the notion of stationarity. If you look into stationarity from a mathematical perspective you may come across many complex definitions that are hard to visualize. In the simplest terms, we want a time series to be stationary in the sense that we know that the value of the time series will oscillate around the mean value in a "predictable way".

We won't ever find time series that are perfectly stationary in the world of securities trading, but our preference is for our time series to have a constant(enough) variance about the mean value.

For an in-depth look at stationarity concepts (also courtesy of image) - https://towardsdatascience.com/stationarity-in-time-series-analysis-90c94f27322

For an in-depth look at stationarity concepts (also courtesy of image) - https://towardsdatascience.com/stationarity-in-time-series-analysis-90c94f27322

Notice that even if the mean value of our time series is variable, it doesn't impact us (since we can calculate a variable mean with a moving average). What is important is that the time series "always go back to the mean" in other words has a semi-constant variance. Following, we will present a variety of ways to determine whether a time series is stationary or not. We will not go into exactly how these tests work, but rather how to analyze their results. For these statistical tests, we will be using the statsmodels library.

A lot of the following tests for both stationarity and cointegration are known as hypothesis tests. Essentially a statistical way for us to assess the probability of a certain assumption, in this case, whether something is stationary or not. To be able to interpret the following tests you need to understand how a hypothesis test works.

- Null Hypothesis - This is our initial assumption. What we first assume to be true: the time series is stationary

- Challenger Hypothesis - This is the challenge to our null hypothesis in this case it is the just the negation: the time series is not stationary

- Test Statistic - A observation we can draw of the data also called the trace statistic

- P-value - The probability of observing the test statistic

Usually, you will know the probability distribution and be able to calculate the p-value for a given observation. But since we are using a module with abstracts away the manual calculation, we have to do a little interpolation to figure out what our test statistic is trying to tell us.

For this example, consider the following graphs, and their results for the Augmented Dicky Fully test

Code Examples for image 1

Code Examples for image 1

from statsmodels.tsa.stattools import adfuller

adfuller(plot1)

adfuller(plot2)

Output

------------------------------

Plot 1:

(-0.439959559222557,

0.9032101486279716,

7,

749,

{'1%': -3.439110818166223,

'5%': -2.8654065210185795,

'10%': -2.568828945705979},

-143.3804208871445)

------------------------------

Plot 2:

(-0.7982895406439698,

0.8196239858542839,

7,

749,

{'1%': -3.439110818166223,

'5%': -2.8654065210185795,

'10%': -2.568828945705979},

513.3832739948602)

Ok, let's break down the values returned by the function adfuller(). The first value in the tuple is the trace statistic.

-

In the case of plot 1 it is approx -0.43996.

-

The second value in the tuple is the p-value.

-

The third value is the number of lags used for the calculation - the lookback window

-

The fourth value is the number of observations used for the ADF regression and calculation

For our purposes, we can ignore the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th values. We care about the trace statistic and the critical values for our confidence interval (the tuple). They tell us the percent change that our test statistic was observed given that the time series is NOT stationary. Meaning the null hypothesis is that the time series is *NOT* stationary and the challenger hypothesis is that it is stationary.

Therefore, what the output for plot 1 is telling us is that there is a 1% chance of our trace statistic being -3.44 if the plot is not stationary. This essentially means that if our trace statistic is close to -3.44 we can be pretty certain that our time series is stationary. Of course, it follows that there is a 5% chance that the test statistic = -2.86 and our time series not being stationary.

As a rule of thumb, anything < 5% means we can be pretty certain. Another thing you might have already noticed is that the trace statistics get smaller as our confidence of stationarity increases. Thus, *in this case*, we can interpret a smaller trace statistic as better evidence for us if we want the time series to be stationary. It naturally follows that if our test statistic = -100 then there is a <<<<< 1% chance that our time series is not stationary.

If trace stat at 1% < trace stat at 5% < trace stat at 10% -> the smaller the value, the more likely that the null hypothesis is wrong

*BUT*

if If trace stat at 1% > trace stat at 5% > trace stat at 10% -> the bigger the value, the more likely that the null hypothesis is wrong

By this logic, we can say that plot 2 is "more stationary" than plot 1, but neither are truly stationary by definition. (Don't say this is real life, math people will murder you.)

from statsmodels.tsa.stattools import adfuller

adfuller(plot3)

Output

(-5.3391482290364545,

4.540668357784293e-06,

11,

745,

{'1%': -3.4391580196774494,

'5%': -2.8654273226340554,

'10%': -2.5688400274762397},

-654.0838685347887)

Note that again the smaller the value of the trace statistic, the more likely our time series is stationary. Since our trace stat of -5.34 < -3.44 it follows that there is a < 1% chance our time series is not stationary. In other words... it is stationary (lol). Another thing to notice is that the second value 4.5e-06 is our p-value, which we can look at as the probability that we observed our test statistic given the null hypothesis is true. Therefore, we can roughly say there is a 0.00045% chance that it is not stationary.

The Hurst Exponent is another criteria we can use to evaluate stationarity. The variance ratio test is just a hypothesis test to see how likely your calculated value of the Hurst exponent is to be true since you are running the calculation on a finite dataset. (And more than likely just a subset of that finite dataset)

The Hurst exponent is pretty complicated, here is an article that covers it rather well - https://towardsdatascience.com/introduction-to-the-hurst-exponent-with-code-in-python-4da0414ca52e, and is also where I got the code for calculating the Hurst exponent from.

def get_hurst_exponent(time_series, max_lag):

'''

Returns the Hurst Exponent of the time series

'''

lags = range(2, max_lag)

# variances of the lagged differences

tau = [np.std(np.subtract(time_series.values[lag:], time_series.values[:-lag])) for lag in lags]

# calculate the slope of the log plot -> the Hurst Exponent

reg = np.polyfit(np.log(lags), np.log(tau), 1)

return reg[0]

The important thing to note here is the value of the lags, it indicates how far back we want to look into our data. In practice, it is often the case that securities prices are not always mean reverting or always trending. Their movement tends to change with time, they may have periods of mean reversion or periods of trending. Therefore, the time window (including both the starting point and the lag value) in which we apply the calculation of the Hurst exponent can yield very different results. In the above code, we start from the latest value and just look back max_lag units of time.

When evaluating the result of the Hurst exponent we note that it is a value between 0 and 1: Hurst < 0.5 implies the time series is mean reverting Hurst = 0.5 implies the time series is a random walk Hurst > 0.5 implies the time series is trending

For information on the variance ratio test (as well as an overview of many of the topics covered in the first half of this README) - https://medium.com/bluekiri/simple-stationarity-tests-on-time-series-ad227e2e6d48 which is also the site I ripped this code from.

import numpy as np

def variance_ratio(ts, lag = 2):

'''

Returns the variance ratio test result

'''

# make sure we are working with an array, convert if necessary

ts = np.asarray(ts)

# Apply the formula to calculate the test

n = len(ts)

mu = sum(ts[1:n]-ts[:n-1])/n;

m=(n-lag+1)*(1-lag/n);

b=sum(np.square(ts[1:n]-ts[:n-1]-mu))/(n-1)

t=sum(np.square(ts[lag:n]-ts[:n-lag]-lag*mu))/m

return t/(lag*b);

In brief, we essentially just want to see a result >= 1 on the variance ratio test. This implies that our time series is not a random walk with >= 90% confidence. Though the details are much more technical than I let on.

Cointegration, for our purposes, is just the process of finding a linear combination of time series that will (linearly combine to) form a stationary (mean-reverting) time series. It is rare(impossible) to find any stock or derivative's price that will be stationary for any meaningful amount of time. Therefore, we need to be able to synthesize a stationary time series using a combination of stocks, or other securities. The following tests will tell you if two or more time-series do cointegrate (linearly combine to form a stationary time series) and give your their hedge ratio

Note that this is for all t such that t is in the bounds of the window in the time series we are analyzing.First and foremost, let's discuss something that you might hear referred to as the hedge ratio. Essentially these are the values a,b,c...n in the above equation that makes sure time series 1 through n add together to a stationary time series. Although we would it would be nice if a,b,c... n were all constant factors, the real world usually is not that nice. Hence it might produce better results if we treated the scaling factors as functions as well. Turning a,b,c...n into a(t),b(t),c(t)...n(t).

Most derivations of the hedge ratio treat the scaling factors as constant. The Kalman filter is one of the few advanced techniques that solve for the scaling factors as variable values.

The CADF test (Cointegrated Augmented Dicky Fuller Test) does not tell us the hedging ratio. Moreover, it can only tell us if a pair (only takes two inputs) of time series cointegrates. It is simple to implement the test, but not very effective, as it is only useful for testing pair trading strategies. (Strategies that use only two time series to create a stationary time series)

from statsmodels.tsa.stattools import coint as cadf_test

cadf_test(input_data["GLD"], input_data["USO"] )

Output

----------------------

(-2.272435700404821,

0.3873847286679448,

array([-3.89933891, -3.33774648, -3.0455719 ]))

Here we notice that our trace statistic is greater than the 99%, 95%, and 90% confidence interval values. A glance at the p-value (0.39) indicates that there is a ~39% change the null hypothesis is false. Which is not strong enough evidence to say that the two time series will cointegrate. This test is fast, but it does not tell us much.

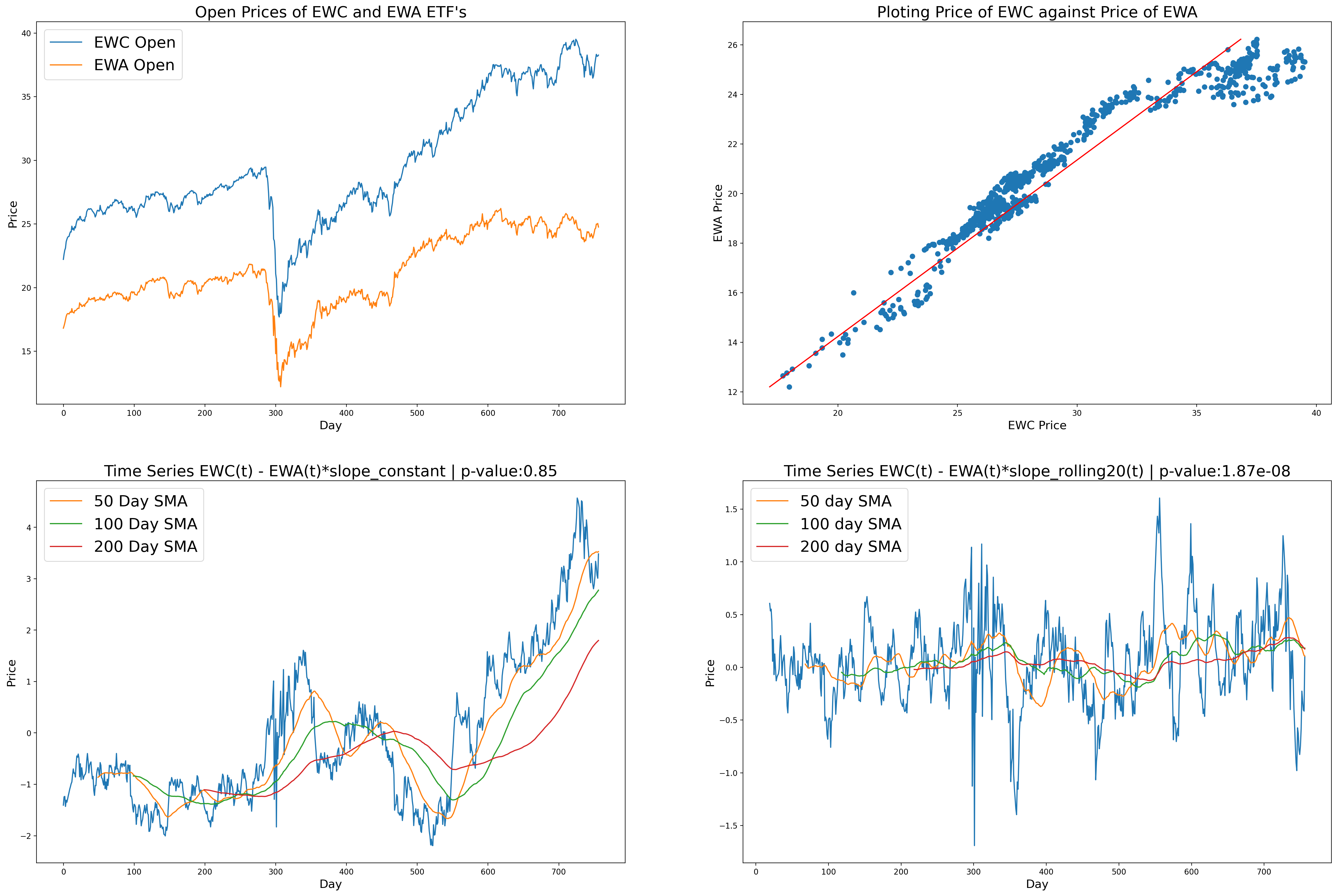

Another method we can use to get the hedge ratio between two stocks is to use linear regression. The concept here is pretty simple, consider the following time series for the EWC and EWA ETFs. A quick CADF test tells us that they do cointegrate. We can verify this by plotting their time series values on a scatter plot, with EWC(t) on the x-axis, and EWA(t) on the y-axis.

In theory, the actual price point values of our time series should be close to and hover around the value of the least-squares regression we ran. (Since our time series value cointegrate). This means that we expect the price to mean revert around this regression line. Therefore, to generate a stationary series we use the following equation.

Now the idea here is that since our price values for EWA and EWC oscillate around the regression line EWA = slopeEWC, the value of the series EWA - slopeEWC should oscillate around 0. Essentially generating a mean reverting time series.

from statsmodels.regression.linear_model import OLS as least_sqaures_regression

linear_reg = least_sqaures_regression(ewc["Open"] , ewa["Open"])

results = linear_reg.fit()

slope = results.params[0]

Calling results.params[0] gives us the slope value. However, you should consult the docs for the exact returns values. As your model might also spit out an intercept value.

But you might have noticed something important. Our regression line really is not that good. You can see periods where many data points are concentrated above the line and other regions where they are clustered below the line. This issue will be reflected in our resulting "stationary" time series.

So the notion of an OLS Regression generating a constant hedge ratio was just a precursor to discussing the Rolling window Linear Regression(which will yield some decent results). The idea here is to treat the slope as a variable rather than a constant. Recall how I stated there are periods where many values are above(or below) the line of best fit, and since this regression line is fitted on ALL of the data it cannot account for regime shifts in the market and can quickly become outdated. Therefore, it makes logical sense to update our linear regression every so often. Then is pretty much was a rolling window OLS is. We are running a regression on a section of the data each time.

As you can see, the results of the rolling regression are much better than that of the regular regression. For the rolling regression in this example, I used a window of 20 days, although it is often good to experiment around and see what works best for your purposes.

from statsmodels.regression.rolling import RollingOLS

rolling_regression = RollingOLS(ewc["Open"], ewa["Open"], window=20)

rolling_results = rolling_regression.fit()

slope_function_20 = rolling_results.params

slope_function_20 = slope_function_20.rename(columns={"Open" : "Slope"})

slope_function_20

Again we will not go into the specifics about how the Kalman filter works. We will just learn how to analyze the results we are getting from it. The Kalman filter can be a whole conversation in and of itself. All we need to know is how to extract the following components from the filter. There are many different packages that provide a Kalman filter. I am using the pykalman package, although it is a little bit outdated. A good exercise would be to figure out how the Kalman filter works and try to implement one yourself.

Gives us:

- Moving Average - Mean value

- Moving Slope - Hedge ratio

- Moving Standard Deviation - Entry and Exit signals

#Dynamic Linear Regression using a Kalman Filter

from pykalman import KalmanFilter

"""

Utilize the Kalman Filter from the pyKalman package

to calculate the slope and intercept of the regressed

ETF prices.

"""

delta = 1e-5

trans_cov = delta / (1 - delta) * np.eye(2)

obs_mat = np.vstack([ewc["Open"], np.ones(ewc["Open"].shape)]).T[:, np.newaxis]

kf = KalmanFilter(

n_dim_obs=1,

n_dim_state=2,

initial_state_mean=np.zeros(2),

initial_state_covariance=np.ones((2, 2)),

transition_matrices=np.eye(2),

observation_matrices=obs_mat,

observation_covariance=1.0,

transition_covariance=trans_cov

)

state_means, state_covs = kf.filter(ewa["Open"].values)

slope = state_means[:,0]

intercept = state_means[:,1]

One important thing to note first is that the Kalman filter also gives us an intercept function. Which is the value that the time series is supposed to mean revert around. The rolling regression just assumes this value to be 0 (and constant).

In practice, we always prefer the Johansen Test over the CADF test. The Johansen test can:

- Tell us if multiple (two or more) time series cointegrate

- It can also tell us the constant hedge ratios for all n time series we pass to it as inputs

- Not dynamic is nature as it assumes the hedge ratios are constant

We will not go into the mathematics of how it works as it is significantly more complicated than linear regression. The key idea here however is that we can cointegrate and find the hedge ratio of more than two time series (which we could not do with our previous regression techniques).

DATA SPECS

--------------------

import yfinance as yf

#Get the data for EWC and EWA

ewc = yf.Ticker("EWC")

ewa = yf.Ticker("EWA")

ewc = ewc.history(start="2019-01-01" , end="2022-01-01")

ewa = ewa.history(start="2019-01-01" , end="2022-01-01")

from statsmodels.tsa.vector_ar.vecm import coint_johansen as johansen_test

input_data = pd.DataFrame()

input_data["EWA"] = ewa["Open"]

input_data["EWC"] = ewc["Open"]

print(input_data.columns)

print(input_data)

jres = johansen_test(input_data, 0 , 1)

trstat = jres.lr1 # trace statistic

tsignf = jres.cvt # critical values

eigen_vec = jres.evec

eigen_vals = jres.eig

print("trace statistics", trstat)

print("critical values", tsignf)

print("Eigen vectors:", eigen_vec)

print("Eigen vals",eigen_vals)

print(eigen_vec[:,0])

OUTPUT

--------------------

Index(['EWA', 'EWC'], dtype='object')

EWA EWC

0 16.816011 22.219603

1 16.994619 22.632471

2 17.208949 22.942117

3 17.467934 23.111017

4 17.735846 23.608328

.. ... ...

752 24.663866 37.990002

753 24.990999 38.330002

754 24.990999 38.180000

755 25.040001 38.189999

756 24.760000 38.270000

[757 rows x 2 columns]

trace statistics [4.88385059 0.4410689 ]

critical values [[13.4294 15.4943 19.9349]

[ 2.7055 3.8415 6.6349]]

Eigen vectors: [[ 1.10610232 -0.55180587]

[-0.55167024 0.50269167]]

Eigen vals [0.0058672 0.00058403]

[ 1.10610232 -0.55167024]

First, we note that the Johansen test comes with n trace statistics, one for each of the n time series we enter as inputs. This is because, as the Johansen test postulates, there are n ways that n unique time series can cointegrate (not all of them will produce a stationary time series). Second, we also need to notice that, unlike the CADF test, the critical values for the Johansen test as printed in the order of 90%, 95%, and 99% confidence (the reverse order of CADF). Therefore, both of our trace statistics do not even come near to the 90% confidence interval, implying that these otwo time series do not cointegrate in any way.

There a couple of things to note about our data that give insight into why we got the following results for the Johansen test.

- The data is from 2019-2020 and as we can see from the linear regression model that there is not a good constant hedge ratio for such a long period of time

- The Johansen test assumes the hedge ratio is constant, because of this it is much less flexible than the Kalman filter/Rolling regression in terms of classifying regression

- Hedge ratios change over long periods of time

- The eigenvector gives us the hedge ratio in matrix form and in the order of the columns in your Dataframe. So the ratio 1.10610232 : -0.55167024 represents EWA: EWC

To test this hypothesis, we can simply shorten the time frame and see if the test gives us different results.

from statsmodels.tsa.vector_ar.vecm import coint_johansen as johansen_test

input_data = pd.DataFrame()

input_data["EWA"] = ewa[ewa["Date"] < datetime.datetime(2020, 4,9) ]["Open"]

input_data["EWC"] = ewc[ewc["Date"] < datetime.datetime(2020, 4,9) ]["Open"]

print(input_data.columns)

print(input_data)

jres = johansen_test(input_data, 0 , 1)

trstat = jres.lr1 # trace statistic

tsignf = jres.cvt # critical values

eigen_vec = jres.evec

eigen_vals = jres.eig

print("trace statistics", trstat)

print("critical values", tsignf)

print("Eigen vectors:", eigen_vec)

print("Eigen vals",eigen_vals)

print(eigen_vec[:,0])

OUTPUT

--------------------

Index(['EWA', 'EWC'], dtype='object')

EWA EWC

0 16.816011 22.219603

1 16.994619 22.632471

2 17.208949 22.942117

3 17.467934 23.111017

4 17.735846 23.608328

.. ... ...

315 13.992842 20.075173

316 13.964949 20.411040

317 14.513505 20.727711

318 14.950492 22.109561

319 14.606481 21.620158

[320 rows x 2 columns]

trace statistics [1.57732397e+01 9.27038992e-06]

critical values [[13.4294 15.4943 19.9349]

[ 2.7055 3.8415 6.6349]]

Eigen vectors: [[ 2.68227333 -1.40388234]

[-2.34546748 0.69904441]]

Eigen vals [4.83912958e-02 2.91521691e-08]

[ 2.68227333 -2.34546748]

Now for our revised test, we have taken a smaller time period as a sample to test our hypothesis as to why the first test yielded a conclusion of non-cointegration. Again we get n trace statistics for our n possible hedge ratios (ways of cointegration). We notice that trstat[0] is >>> it's 99% confidence interval critical value of 19.9, while trstat[1] << its corresponding 90% confidence critical value of 2.7. This tells us that the first set of eigenvectors is a hedge ratio that will yield a cointegrating series, while the second set will not.

The eigenvectors are not given as transposed lists. So 2.68 and -2.34 are the values of the first vector, and -1.40 and 0.699 are the values of the second.

This is the part where we turn the math into an actual trading strategy. We need to translate our mathematic factors into indicators for the algorithm of how many shares of which stocks to buy or short. We will look at two very simple mathematical principles that can be useful in this process.

The half-life of mean reversion is an important concept when evaluating the speed at which a strategy can provide returns. It is pretty self-explanatory, it simply gives us an insight into how long a strategy takes to mean revert (and thus provide profit). Naturally for example, if the half-life of mean reversion is 20 days, we can expect it to revert every 40 days.

from statsmodels.tools.tools import add_constant

#Half life of mean reversion calculation is a regression between

#y(t) - y(t-1) as the dependent variable

#y(t-1) as the independant variable

y = stationary_series["Plot"]

y_lagged = stationary_series["Plot"].shift(1)

dependent = y - y_lagged

y_lagged.iloc[0] = y_lagged.iloc[1]

dependent.iloc[0] = dependent.iloc[1]

model_1 = least_sqaures_regression(dependent, add_constant(y_lagged))

results_1 = model_1.fit()

print(results_1.params)

halflife = (-np.log(2)) / results_1.params[1]

print(halflife)

Quite importantly, the half-life of mean reversion also gives us significant insight as to what our lookback window values should be. Naturally this will not help with the rolling regression window lookback(if you were considering that) because the rolling regression is used to create the mean-reverting series, and the halflife is a property of that created series.

We can use the half-life to determine windows for our standard deviation calculation. The concept here is pretty intuitive. If our mean reversion halflife is 20 days, we would not a standard deviation window < 20 days as that value for the standard deviation would be too sensitive. Naturally, we would want our window to be k*20. Where k is some small multiple. Maybe we would want 60 or 80 days for a more robust sense of standard deviation (standard deviation covering 1 or more reversion to the mean).

All of our entry and exit signals will be based on the standard deviation of the current price to the mean. This makes logical sense if we consider the fact that we have essentially just combined a bunch of time series in a practical way to generate a stationary time series. Since our time series is stationary, we "know it will revert to its mean value". Therefore, when the standard deviation of the current price (for our generated time series) from the mean is >> 0 we should short our combination of securities because the price of our combination is likely to go down toward the mean. When the standard deviation is << 0 we should be long on our combination because the price (value) or our combination of securities is likely to go back up toward the mean.

Recall that standard deviation is:

The important thing to consider here is the value N, this is the number of data points we want to take into consideration when calculating the standard deviation. We can find the optimal value of N in several ways.

- Using the Kalman Filter

- Using the Half-life of mean reversion

- Optimizing the parameter on data (Dangerous)

How far the price deviates from the mean before it reverts is a variable to us. We have the standard deviation as a guiding light, but in we still have to decide how we are going to use it. One way to linear scale into our portfolio as we deviate further from the mean. In order words to short our combination as we go further above the mean, and to continue to short if we keep getting further. Then to go long when we are below the mean, and keep going long as we remain below the mean. In other words to buy an amount relative to our standard deviation.

where k is some constant scaling factor.The problem with this strategy is the capital usage. As I said, the only thing we can be fairly confident about is the fact that the price will mean revert, but the standard deviation from the mean at any given time is a variable. This means we could effectively get an infinite standard deviation, thus linear scaling requires (technically) infinite capital.

To get around this issue we can use Bollinger bands. Which is just a set value for the standard deviation at which you will go long, or go short on the stock. For example, if the standard deviation is >=2 we go short, if it is <= -2 we go long. A simple entry and exit signal for our trades.

lookback = k*halflife

moving_variance = np.zeros([len(average)])

for i in range(lookback-1, len(moving_variance)):

moving_var = 0

for loop in range(lookback):

moving_var += (stationary_plot["Plot"].iloc[i-loop] - average[i])**2

moving_var /= lookback

moving_variance[i] = moving_var

moving_std = np.sqrt(moving_variance)

Here we can see all the standard deviations of our stationary plot, usually, we optimize our entry and exit standard deviation values on the data. But it is important to note that that can lead to data snooping bias in our model. So let's just pick some values based on this graph. 1.8 and -1.2 look like good starting values.

To test our strategies with a simulated broker, I used backtrader you can find the code in the following file: backtest_ewc_ewa_pair_trade.py

At this point, it seems that the core principles behind mean-reverting strategies are all mostly the same. You might be thinking to yourself: So where does the individuality come from, if any nerd can build a mean-reverting strat, what separates the winners from the losers? (OK, first of all, bad mentality. We are all here to have fun :) ). I will take a few pages out of EP Chan's first book: Quantitative Trading, and give some insight into what to do from here on.

The performance of a strategy is very sensitive to details, small changes in these details can bring about substantial improvements. These changes can be as simple as changing the look-back period for determining the moving average or entering orders at the open rather than at the close. Backtesting a strategy allows us to experiment with every detail. Just because the core concepts are the same, does not mean the strategy is not unique

Different people have different investment styles. How you use your strategy will be unique to your situation. What you expect from it, what you put into it, and in what markets do you think it is viable are judgment calls that you make. Having a solid trading model is not enough, you need to be good enough to apply it to its full potential.