An introduction to Shaders, GLSL and the graphics pipeline ITP unconference, spring 2017.

- What are shaders and what are they used for?

- What role the GPU plays

- Where does OpenGL fit into all of this?

- An introudction to GLSL and its syntax

- What textures are used for

- How shaders fit into frameworks like Processing, p5.js, Three.js, OpenFrameworks and Cinder.

- Inigo Quillez - Don't be fooled by the website, this guy is a genius!

- Robert Hodgin

- Reza Ali

- Simon Geilfus

- Jaume Sanchez

- Online Shader Editor

- GLSL quick reference

- The Book of Shaders

- ShaderToy

- LearnOpenGL

- OpenGL in Cinder

- oF: Introducing shader

- Reza Ali's F3 App

- Cacheflowe

- Ken Perlin's Syllabi

- WebGL fundamentals

- GPGPU and WebGL

Shader: A shader is a program that runs on the GPU ( graphics processing unit) as opposed to the CPU ( central processing unit). There are several different types of shaders, each of which performs a specialised function. Shaders are special because they take advantage of the GPU's ability to do parallel computation.

GPU: Pretty much all modern computers have a graphics card. The work-horse of the graphics card is the GPU ( graphics processing unit ), but it also houses its own special type of memory (GDDR SDRAM). The GPU is a purpose-built chip that specializes in parallel computation.

OpenGL: OpenGL stands for 'Open Graphics Library' and is a cross-language, cross-platform application programming interface for rendering 2D and 3D vector graphics. From a more practical standpoint, OpenGL is an API that allows us to communicate with the hardware dedicated to graphics, ie.the Graphics card.

GLSL: 'GLSL' stands for OpenGL Shading Language and is a high-level shading language based on the syntax of the C programming language. GLSL is the language we use to write shader code.

Shaders run on the GPU, which has an entirely different architecture to the CPU. GPUs are designed and built for parrallel computation ( The book of shaders has an excellent analogy here ). Data (vertices, attributes, textures etc.) is passed to the GPU where different shaders are responsible for different stages of the pipeline. Data and orders must follow a path and have to pass through some stages, and that cannot be altered. This path is commonly called The Graphics Rendering Pipeline. Think of it like a pipe where we insert some data into one end—vertices, textures, shaders—and they start to travel through some small machines that perform very precise and concrete operations on the data and produce the final output at the other end, ie. the final rendering.

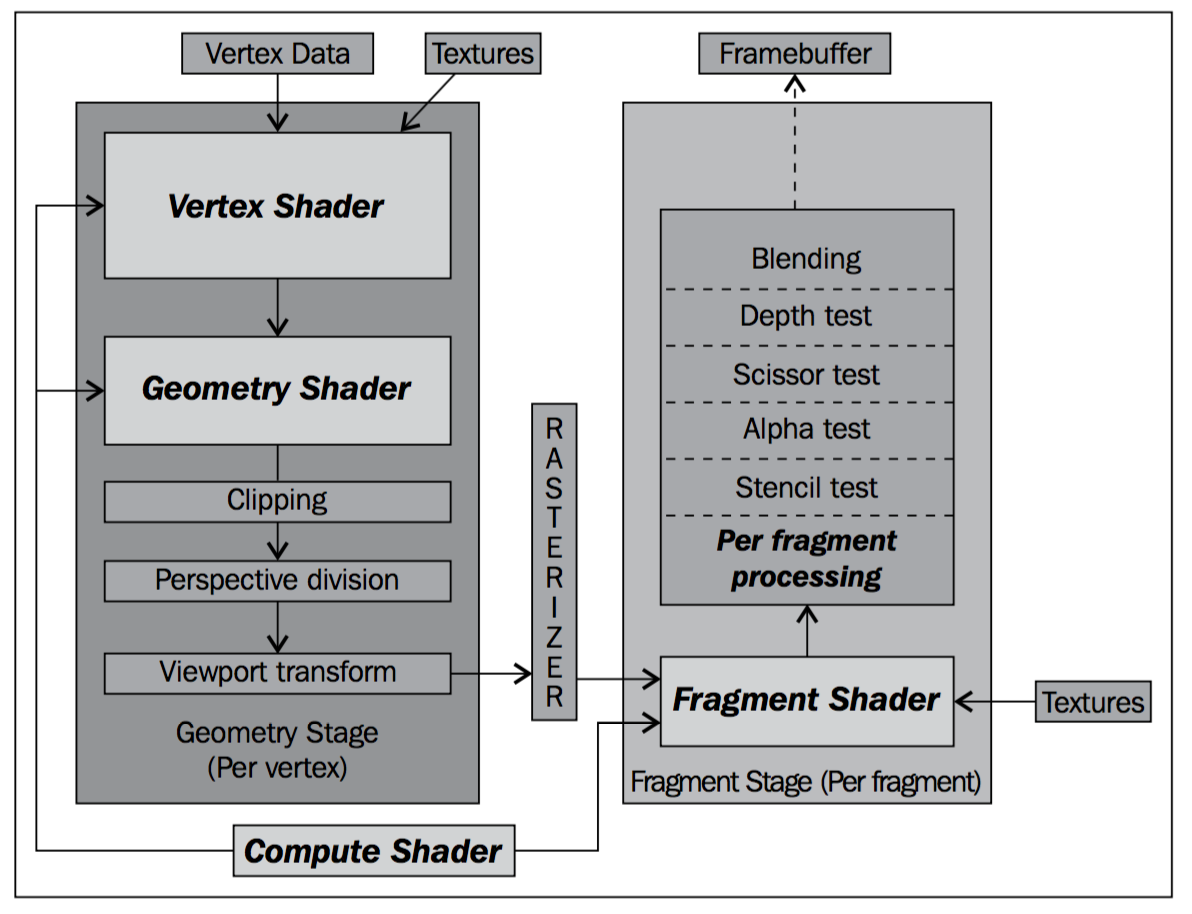

The diagram below shows a simplified view of the graphics pipeline:

In a nutshell, the rendering pipeline is responsible for rendering the final image onto your display. An important role that the various shaders play is transforming coordinate systems. Why is this important? Well, because OpenGL expects every vertex that goes through the pipeline to be represented in normalized device coordinates, ie to have a value between -1.0 and 1.0. Shaders make use of transformation matrices to achieve this and convert a 3D objects local coordinates to XY coordinates for your display. You can find an in-depth description of the processes here.

The following diagram shows the programmable pipeline in a bit more detail, and highlights the four types of shaders in bold.

As you can see, four shader types are defined: Vertex Shader, Geometry Shader, Compute Shader, and Fragment Shader. All shader code is written using GLSL. We'll be focusing on the vertex shader, and fragment shader today as they're the most important in the pipeline because they expose the pure basic functionality of the GPU. Note, if you do write your own shaders, it's mandatory that you have both a vertex and fragment shader. The compute shader and geometry shader are both optional and are only used in special circumstances ( we won't be covering these as they're a more advanced topic ). There's another type of shader called a Tessellation shader, but that's also beyond the scope of this intro.

The vertex shader code runs once for every vertex in the scene. All the vertices in the scene are passed to the GPU in a buffer. [The role of the vertex shader]. For example, if you're trying to render a single triangle, you'll pass vertex data for 3 vertices to the GPU, and the vertex shader will run a total of 3 times every frame. The most important aspect of it is to provide the vertex positions to clip coordinates, to take us to the next stage.

In essence, a fragment shader's task is to output a single RGBA colour that will represent a single pixel on your screen. Unlike the vertext shader, the fragment shader will run once for every pixel in your display window ( you can think of the terms 'fragment' and 'pixel' being interchangeable). Fragment shader code is executed hundres, or thousands, of times simultaneously. In other words, the code you write behaves differently depending on the position of the pixel in the window. The same piece of code runs once for every pixel. For example, if you have a window that's 1024x768 ( that's a total of 786 432 pixels). If your program is running at 60fps, the fragment shader is running ~47,185,920 times a second. In other words, fragment shaders are designed to be fast. Very, very, very fast. Think of it this way, the role of all the code in the fragment shader is to set the RGBA value for each and every pixel.

Variables in are statically typed. In other words, you have to be explicit about declaring whether or not a variable is an int or a float, for example.

Texture sizes should always follow the power-of-2 rule, ie. 64x64 (2^6), 128x128 (2^7), 256x256 (2^8), 512x512 (2^9), 1024x1024 (2^10) etc. Textures are passed from the CPU to the GPU where they're stored in memory. To access the texture data, the texture has to be bound and is read inside the shaders as a uniform variable ( usually a Sampler2D ).

We'll be using shaders in two different ways today, which I've found can cause some confusion. The first method is to utilize shaders to render geometry, ie. we'll control the colour, lighting, textures etc. The second way, which perhaps is a little harder to grasp conceptually, is that we'll be drawing inside the fragement shader ( this is what things like shadertoy and the book of shaders focuses on). In essence, we're not using shaders to render a 'physical scene', but rather we're simulating these scenes (both 2D and 3D) inside the fragment shader.