Repository to experiment with LLMs as if they were CPUs by training and testing them with different embeddings. More than a repository, I feel like the main place where things will happen in this repo, is the README.md, and will likely use the rest of the repository to store the examples.

LLMs (mainly Language Models that follow the Transformer architecture: either using the Encoder-Decoder, Encoder only, or Decoder only architectures) behave in a similar way as a CPU in a computer works.

If we consider them as a black box; they receive an input, and produce an output. Digging a bit deeer, we find that the input to the model is text in a natural language and output is text in a natural language as well (we are not considering other kinds of inputs to transformers, just yet. In order to keep it simple and lay the ideas that refer to the repository; somehow they can be extended to music and visual transformers, as well as transformers that receive any other kind of input).

We can agree that such text in natural language is similar to high level programming languages like python, if we keep the analogy that LLMs behave like CPUs. Because of that, if we dig further the natural text is translated into tokens using the tokenizer; such tokens are integer ids, that represent the introduced text. Some tokenizers will create embeddings from the input text mapping each text token to a numerical ID, others will map the input text to a different length embedding.

The tokens introduced into the LLM are the machine code, if we resemble the metaphor to how programming languages get to run in a CPU. Because of that, code compiled for a certain CPU architecture, will not work in a different CPU architecture (ARM vs. x86); in a similar manner, it is expected that the same happens for the LLM, unless...

And this is where this gets interesting; LLMs are not a 1 to 1 mapping (or metaphor) to CPUs, in this case LLMs are "trained" CPUs in a way in which, the LLM will (likely) be capable of generating output for a given input in a embedding language (I am coining this term as the way a natural text gets transformed into the input ids introduced in the LLM), if and only if, the model is trained with such embeddings, otherwise, it will not be able to generate coherent computations, given a certain input. We need to define what coherent means in this case; for the case of CPUs it would be like when you point the CPU to a data map in memory and starts executing the data as if it were code (this is one of the sources of cybersecurity issues: buffer and heaps overflows). So, we can consider that coherent generations are related to generations that produce semantically correct text, and that the output is expected from the input, at least in a wide variety of data inputs (it is expected that even for fine tuned LLMs, they will hallucinate or generate weird output in certain occassions).

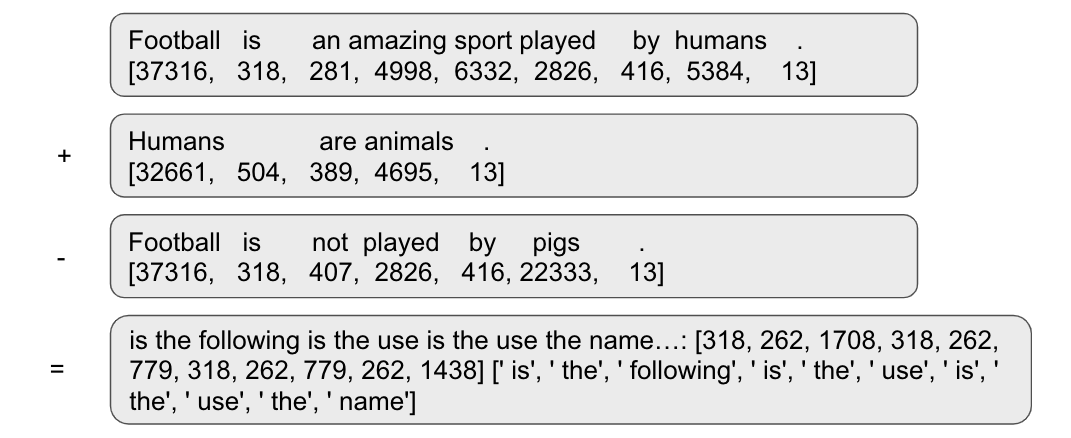

Some of the main ideas behind the experiments in this repository are not new, and come from the very early days of text embeddings in NLP (Natural Language Processing); like the experiments with semantic (arithmetic) operations with embeddings, early discovered in word2vec; in which the user can apply arithmetic operations on the embedding vectors and yet get interesting results; e.g.: King + Woman = Queen.

This repository has been motivated by the recent work in these repositories:

The idea that an LLM behaves like a CPU is not something new, it has been explained in multiple podcasts, videos, blogs, papers... It can certainly do computations and we can train them to do certain kinds of computations by following the natural language explanations.

It is remarkable that somehow the tokenizer behaves in some way as the compiler in a programming language, as the natural language text (source code in a programming language), gets compiled into a bunch of numbers that represent data and instructions, the machine code, the executable.

This kind of LLMs is interesting, from the point of view of the comparison between the LLM and the CPU. Encoder-Decoder architectures have been around much before the appearance of the LLM (e.g.: the autoencoder), and have been the base of the resolution of many problems, even out of the AI ecosystem (e.g.: Error Correcting Codes to fix communication errors in a transmission). The objective of the encoder is to translate the input data into a "latent space", such latent space is later used as the data to work with, make computations with, to recover the representation from... Such architecture is also common with compression algorithms.

For the case of the LLM, the natural language is introduced in the LLM, it is translated to tokens, and the Encoder produces the latent space; if we follow the ideas presented up until this point; the input ids introduced in the LLM were a metaphor for the machine code, or executable if we refer to the CPU; so the output from the Encoder, is a kind of enriched machine code, machine code that has been filled with metadata by the LLM. In a certain way it is like if the compiler added canaries to the program, and debugging metadata that can later be used by a debugger. In some kind of way it is different in the case of the LLMs; in our case the Encoder kind of programs how it wants the Decoder to behave under the given latent space. Later on the Decoder (this is much more like the CPU in this case so, an alternative title would be decoders_are_trained_cpus :)), will read on the latent space as well as the SOS (Start Of Sentence) token; and will produce the output.

I have a feeling that the usage of an Encoder helps the Decoder to have a richer amount of possible programming modes, it has been seen with the T5 models by Google; how greatly the model could be programmed by using prefixes in the prompt that were easily identified by the model, to compute the output.

This kind of models is of great interest as well, as they produce an embedding, instead of generating text like you would have in other kind of LLMs. The encoder produces such embeddings that could be of great use, in cases like semantic search, document retrieval, topic modelling... In this case the richer the embedding, the more use we can have for the model.

For the case of this repo; experiments using the embedding generated from Encoder only models, as the input to Decoder only models would be highly interesting. Swapping the Encoder for another Encoder in the model will likely cause issues, unless a fine tuning is done with the new Encoder. It is likely that certain capabilities for the model will prevail, as it happens when we attempt transfer learning with CNNs in computer vision related use cases.

This kind of models have become the "de facto" if we analyze the ecosystem nowadays; GPT and LLaMA based models have become the way to go for text generation; the internal state that the tokenizer generates for the decoder to work on the data, is rich enough that there is no need to add more "context" or "metadata" to the embeddings for them to generate high quality text. They are simpler models that Encoder-Decoder models, that require the training of the Encoder in addition.

There have been several works that study the way LLMs work down to a deep level, and that even manually program the embedding matrices and weights in the model manually, in order to do a certain specific task, this one does a very detailed tour:

- TODO: Add ref to the jupyter notebook that trains LLMs manually

Following the ideas presented in the repositories that were previously mentioned, and taking the code from https://github.com/MF-FOOM/wikivec2text/blob/main/test.py as a starting point to use the MF_FOOM's model and the embeddings generated by GPT2 tokenizer, we can get interesting results (even though the model has been trained with a completely different embedding, text-embedding-ada-002). And yet the model generates some semantically correct text, even though it does not make a lot of sense given the inputs given to the model, it is expected that if we follow certain fine tuning on such model with a different tokenizer, better results will be generated.

As an example, for a sentence with X words, the GPT2 tokenizer will generate likely X input ids, or very close to X, as the embeddings of gpt2 usually map a token to each word,

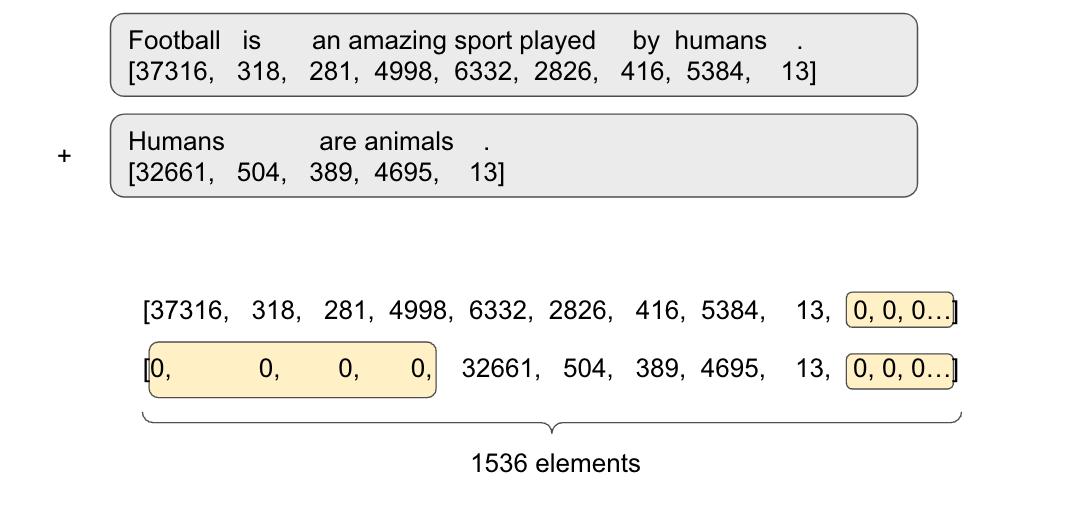

the embedding size generated by text-embedding-ada-002 is 1536; because of that, and as MF_FOOM's model uses embeddings from text-embedding-ads-002, we need to pad the embeddings.

For the experiment, I have considered padding the 0s on the right of the sentence. If we have a look at the example given in the following image, we can see that even the sentences

that will be operated on, do not have the same length in their embeddings, because of that, prior to embedding to fit the length of text-embeddings-ada-002, we first need to pad

the smaller vector to match the size of the bigger vector in the operation, for this kind of case, the padding was done on the left:

As mentioned earlier, semantic arithmetic operations is the main objective of the experiments, to see if the CPU (in our case the LLM), is capable of getting the semantic information

from different pieces of text, and binding them together by using the vector embeddings, and different arithmetic relationships. In this manner, the result of the arithmetic operation

over the embedding is given to the LLM to generate text, and the output is checked. In this example, there is not much of semantic sense, and the operation did not execute correctly.