The University of Melbourne

In this workshop you will be introduced to Unity, a powerful cross-platform game engine which facilitates the construction of rich interactive scenes. You'll also familiarise yourself with the process we'll follow for subsequent workshops -- namely, cloning and opening a Unity project from GitHub.

The root directory of this repository is a Unity project that we've already created for you. After cloning the repository to your computer, you're going to open it in Unity. This can be done easily with Unity Hub, which is an application that manages Unity installations and projects on your computer (it should be automatically bundled with your install). Once you've launched Unity Hub, ensure the 'Projects' tab on the left-hand panel is currently selected. Then, click 'Open' and navigate to the locally cloned repository. Opening it will add it to the list of tracked projects in the same window. Now simply click on the project to open it in Unity.

Note

Opening a project in Unity for the first time can take a while, since cached library files need to be generated. However, subsequent loads of the same project should be a lot faster provided that you don't delete these files (they can be found in the 'Library' folder). We rarely ever commit these files to a git repository as they are generally very large and can be re-generated locally as seen here.

Once the project is open in Unity, navigate to open Scenes > Main in the '

Project' panel.

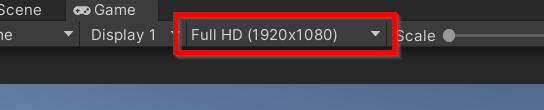

At the top center of the editor window you should see a README. If the layout looks strange, you may need to explicitly set the resolution

in the Game tab to Full HD (1920x1080):

Click the play button again

to stop the game.

Make sure you understand the difference between the Scene tab and the Game

tab.

When you click the play button you are automatically switched to the game tab,

and then back to the scene tab when you click it again to stop the simulation.

Although the switch is automatic, it is possible to manually switch between

these at any point.

Warning

Any changes you make to the scene while the game is running are temporary. A common rookie trap is to manually switch to theScenetab while the game is running, then continuing to work on the project thinking it will be saved (here's a meme for comic relief when it inevitably happens to you).

Now explore the scene. In the Hierarchy (left-hand panel) you can see all

the GameObjects that are part of the scene:

- Main Camera - The 'viewpoint' of the player.

- Directional Light - The main light source in the scene (simulates a 'sun' of sorts).

- Top Ball and Bottom Ball - Physics objects that collide with each other and change color on collision.

- Plane - Represents the 'ground' in the scene.

- Canvas - Defines a two-dimensional overlay serving as a 'user interface'.

- UI Text - Text that is part of this overlay.

- 3D Text - Text embedded as an actual three-dimensional object in the scene.

Note that not all GameObjects require a visual body (e.g. the camera and light

source above). Recall that GameObjects are composed of

one or more components. Aside from the default Transform component,

arbitrary compositions of additional components are allowed,

including an entirely 'empty' object (turns out there's a use for this!). We'll

examine components in more detail next.

Click on the Top Ball object, and then look at the Inspector (right-hand

panel)

where you can see the attached Components. The components

are Sphere (Mesh Filter), Mesh Renderer, Sphere Collider, Rigidbody

and Change Color On Collision (Script). To learn more

about, them click on the ? and read the documentation from Unity. Notice how

there is no documentation page for the script. That's because this is a custom

written

C# component specific to this project (more details in the next section).

We can create custom components to attach to GameObjects by writing C#

scripts.

The Change Color On Collision (Script) component is an example of this. Click

on the three dots in the top-right corner of the component, and select 'Edit

Script' from the menu which appears.

You should see the following code open up in Visual Studio (or equivalent):

using UnityEngine;

public class ChangeColorOnCollision : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] // SerializeField exposes 'changeColorTo' in the editor.

private Color changeColorTo = Color.white;

private void OnCollisionEnter()

{

// First we'll get the material used by this game object's 'Renderer'.

var material = GetComponent<Renderer>().material;

// Now we can change the colour of the material.

material.color = this.changeColorTo;

}

}The goal of this component is to change the color of an object when it collides

with another object. In particular, note the use of the private

variable changeColorTo. By attaching the special attribute [SerializeField]

to this variable,

we allow its value to be set within the

Unity interface, and also saved as part of the scene.

Note

If you have used Unity before it's likely you have seenpublicvariables used instead ofprivatevariables with associated[SerializeField]attributes. Both methods are valid ways to 'expose' a variable within the Unity editor interface. However, good OOP practice encourages encapsulation of object state, hence why we'll tend to prefer the[SerializeField] privateapproach in code examples. While you are encouraged to do this as well, for the purposes of assessment, it doesn't matter which approach you use.

If you expand the Change Color On Collision (Script)

component in the Unity editor, you can see 'Change Color To' listed, and the

colour it is currently set to. Notice how the Unity editor detects not only the

variable name, but also the type of that variable. In this case

there's even a special dialog box dedicated to colour picking! This is an

extremely powerful feature of the editor -- a large number of different data

types

are automatically detected out-of-the-box. As an exercise, try changing the

colour for one of

the balls, and run the game again.

The best way to learn Unity is to use it. The objective for the remainder of this class is to start with a blank scene and recreate the one you explored as closely as possible. This will get you accustomed to various commonly used components, as well as the interface more generally.

Click File > New Scene to start from an empty scene. You should be able to

see that it comes with two GameObjects pre-instantiated: Main Camera and

Directional Light.

Add another GameObject by clicking the +, or right-clicking in the

hierarchy.

With the help of your tutor and the original Main scene, make sure that

all GameObjects have the components required and equivalent parameters.

If you finish early try making some modifications for an extra challenge:

- Add another ball to the scene that changes to a different colour on collision.

- Change the shape of one of the balls so it is a cube instead.

- Write a script that changes the shape of the cube to a sphere on collision.

Don't forget to save your scene periodically.

Good Luck!