The following notebook implements and demonstrates many of the key concepts, methods and algorithms in the University of Bristol Image Processing and Computer Vision course. The notebook covers the following topics:

- Image Acquisition and Representation

- Modelling Images

- Sampling

- Convolutions

- Frequency Domain and Image Transforms

- Fourier Analysis

- Fourier Transforms

- Convolution Theorem

- Hough Transforms

- Segmentation

- Thresholding

- Edge-based methods

- Region-based methods

- Statistical methods

- Object Detection

- Integral Images

- Harr-Like Features

- Ada-Boosting

- Detecting Motion

- Optical Flow Equations

- Lucas-Kanade Method

- Stereo Vision

- Epipolar Geometry

- Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT)

- Spatial Gradient Descriptors

from __future__ import division

from itertools import *

from functools import partial

from operator import getitem, mul, sub

from random import sample, seed

from collections import Counter

from math import factorial as fac, cos, sin

from time import sleep

import sys

print sys.version

import cv2

import numpy as np

import scipy as sp

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

from IPython.display import clear_output

from collections import Counter

from scipy.cluster.hierarchy import dendrogram, linkage

# helper functions

def indices( image ):

return product(*map( range, image.shape ))

def load_image( name ):

image = cv2.imread( 'images/%s' % name, cv2.IMREAD_COLOR )

return cv2.cvtColor( image, cv2.COLOR_BGR2RGB )

def show_image( image, ax = None, **kwargs ):

''' Given a matrix representing an image,

(and optionally an axes to draw on),

matplotlib is used to present the image

inline in the notebook.

'''

if ax == None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow( image, cmap = 'Greys_r', **kwargs )

ax.axis( 'off' )

else:

ax.imshow( image, cmap = 'Greys_r', **kwargs )

ax.axis( 'off' )

return ax

def ideal_grid_size( n ):

bound = 1 + int( np.ceil( np.sqrt( n ) ) )

size = ( 1, n )

for i in range( 1, bound ):

if not n % i:

j = n // i

size = ( i, j )

return size

def show_images( images, titles = [], orientation = 'horizontal',

figsize=(32, 32), structure = [] ):

if not structure:

l = len( images )

if orientation == 'vertical':

ncols, nrows = ideal_grid_size( l )

else:

nrows, ncols = ideal_grid_size( l )

structure = [ ncols ] * nrows

for n in structure:

fig = plt.figure( figsize = figsize )

for plotnum in range( 1, n + 1 ):

ax = fig.add_subplot( 1, n, plotnum )

if titles:

ax.set_title( titles.pop(0) )

plotnum += 1

ax.axis( 'off' )

ax.imshow( images.pop(0), cmap='Greys_r' )

plt.show()

def to_255( img ):

out = img - np.min( img )

return out * 255 / np.max(out)

def gauss( s, m, x, y ):

xm, ym = m

return np.exp(-((x-xm)**2 + (y-ym)**2)/(2*s**2)) / (2*np.pi*s**2)2.7.12 |Anaconda custom (64-bit)| (default, Jun 29 2016, 11:07:13) [MSC v.1500 64 bit (AMD64)]

An image is modelled by a quantized function mapping a coordinate space to a colour space, an image

\begin{align*} X^n &= {0 \leq x < w\ |\ x \in \mathbb{N}} \times {0 \leq x < h\ |\ x \in \mathbb{N}} \ C^n &= {0 \leq x < 255\ |\ x \in \mathbb{N}}^3 \ \end{align*}

This relationship is typically encoded using three matrices - one for each colour channel.

When a signal is captured or a function is computed and stored on a computer, there is a specific finite density in which the information can be kept at. While the function

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 3, figsize = (20, 10))

for i, ax in enumerate(axs.flatten()):

xs = np.arange( -np.pi, np.pi, 1 / (i+1) )

ys = np.sin(2*np.pi*3*xs) + np.cos(2*np.pi*xs)

ax.plot( xs, ys )

ax.set_xlim([ -1, 1 ])

ax.set_ylim([ -2, 2 ])

ax.scatter( xs, ys, color='red' )

xs = np.arange( -np.pi, np.pi, 0.01 )

ys = np.sin(2*np.pi*3*xs) + np.cos(2*np.pi*xs)

ax.plot( xs, ys )

ax.set_title( '%i samples per unit' % (i+1) )

plt.show()An analogue signal containing components up to some maximum frequency

Consider viewing a manifestation of Newton’s rings under a microscope (left figure). After taking a small image of the phenomenon with a cheap webcam (right figure). Why does additional structure appear to exist in the photograph that wasn't visible to the human eye?

The image taken with the webcam was sampled at too low a frequency (below the Shannon-Nyquist limit) and, thus, it shows artefacts not present from natural phenomena (concentric rings at top, bottom, left and right). This is known as aliasing. Classic, similar effects can be seen when a striped shirt is undersampled and appears with aliasing on TV.

Consider taking a 25 fps video of a car wheel spinning, when viewing the video it appears as if the car wheels are moving backwards and have been coloured strangely.

The camera takes a sample of the world every 1/25th of a second. If the car wheels have turned from frame to frame enough to having revolved just under a full revolution, we are presented with consecutive frames in which the wheel seems to turn slowly backwards. This can be accounted for by increasing the framerate of the camera or removing the pattern from the wheel so that no rotation can be percieved. This is an example of the Shannon-Nyquist theorem as the sampling rate across time is less than the threshold of two times the rotational frequency of the wheel.

We can filter symbols and signals in the spatial/time domain to introduce some form of enhancement to the

data and prepare it for further processing or feature selection. Many spatial filters are implemented with

covolution masks. If

It is extended into multiple dimensions in the obvious way, and is written in shorthand as

The core principle of Fourier series is that the set of real periodic functions can be constructed as a Hilbert space of

infinite dimensions with sine and cosine functions of different frequencies forming the basis vectors. More specifically,

considering any real valued function

As sin(0) = 0 and cos(0) = 1, this is often written as,

This allows any arbitrary periodic function to be broken into a set of simple terms that can be solved individually, and then combined to obtain the solution to the original problem or an approximation to it.

As mentioned previously, the functions are elements of a vector space with different frequencies of cosine and

sine functions forming the basis vectors. This fact allows us to understand how we can compute the Fourier

coefficients. Consider a more general

for coefficients

Going back to our more specific case for Fourier analysis, for functions

We choose the limits as such and divide by

\begin{align*} \cos nx \cdot \cos mx &= \frac{1}{\pi} \int_0^{2\pi}{ \cos nx \cos mx dx} = 0 \ \cos nx \cdot \sin mx &= \frac{1}{\pi} \int_0^{2\pi}{ \cos nx \sin mx dx} = 0 \ \sin nx \cdot \sin mx &= \frac{1}{\pi} \int_0^{2\pi}{ \sin nx \sin mx dx} = 0 \ \cos nx \cdot \cos nx &= \frac{1}{\pi} \int_0^{2\pi}{ \cos nx \cos nx dx} = 1 \ \sin nx \cdot \sin nx &= \frac{1}{\pi} \int_0^{2\pi}{ \sin nx \sin nx dx} = 1 \end{align*}

So applying these identities to the case of

\begin{align*} a_n &= \int_{-\frac{T}{2}}^{\frac{T}{2}}{ f(x) \cos\Big( \frac{2\pi n x}{T}\Big) dx } \ b_n &= \int_{-\frac{T}{2}}^{\frac{T}{2}}{ f(x) \sin\Big( \frac{2\pi n x}{T}\Big) dx } \end{align*}

For the saw tooth function

def approx_saw_tooth( N, ax ):

s = lambda x : (((x-np.pi)%(2*np.pi))/np.pi) - 1

term = lambda x, n : ((-1)**(n+1)) * sin(n*x) / n

series = lambda x : imap( partial( term, x ), count(1) )

s_N = lambda x : sum(islice(series(x), N+1)) * 2 / np.pi

xs = np.linspace( -10, 10, num = 1000 )

ys = map( s, xs )

ax.plot( xs, ys, label='original function' )

ys = map( s_N, xs )

ax.plot( xs, ys, c = 'r', label='approximation' )

ax.set_title( 'Approximation of %d terms' % N )

ax.set_xlim( -3*np.pi, 3*np.pi )

ax.set_ylim( -1.5, 2.5 )

ax.legend()

for N in range(1, 10) + range(10, 100, 5) + range(100, 1001, 300):

fig, axs = plt.subplots( 1, 2, figsize=(6, 3) )

approx_saw_tooth( 5, axs[0] )

approx_saw_tooth( N, axs[1] )

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

clear_output( wait = True )The motivation behind Fourier transforms is to produce a function

Formally defined, the Fourier transform

where

The concept of the frequency domain follows from Euler's Formula for

An image quantized to

xlim, ylim = ( -np.pi, np.pi ), ( -np.pi, np.pi )

imsize = 50

x, y = np.meshgrid( np.linspace(*xlim, num=imsize),

np.linspace(*ylim, num=imsize) )

functions = [

np.cos(2*np.pi*x),

np.sin(2*np.pi*(x + y)),

np.cos(2*np.pi*x) + np.sin(2*np.pi*(2*x + y))

]

fig, axs = plt.subplots( 2, len(functions) )

top, bottom = axs[0], axs[1]

for ax1, ax2, f in zip( top, bottom, functions ):

show_image( f, ax1 )

z = np.fft.fft2(f)

q = np.fft.fftshift(z)

mag = np.absolute(q)

show_image( mag, ax2, interpolation = 'none' )

ax1.set_title('spatial domain')

ax2.set_title('frequency domain')

plt.show()lena = load_image( 'lena.bmp' )

image = cv2.cvtColor( lena, cv2.COLOR_RGB2GRAY )

f = np.float32( image )

z = np.fft.fft2(f)

q = np.fft.fftshift(z)

mag = np.absolute(q)

ang = np.angle(q)

a = np.real(q)

b = np.imag(q)

titles = [ 'input image',

'magnitude spectrum',

'phase spectrum' ]

images = [ image,

np.log(1 + mag),

ang ]

fig, axs = plt.subplots( 1, 3, figsize=(9, 3) )

for ax, image, title in zip( axs, images, titles ):

show_image( image, ax )

ax.set_title( title )

plt.show()A simple example is to consider speech recognition between two utterances

To solve this we take the Fourier transforms for both utterances to get

Fourier transforms in higher dimensions follow quite naturally from the one dimensional case, $$ F(u, v) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}{f(x, y)\ e^{-2\pi i(ux + vy)} dxdy} $$ For example images are functions of two variables, and hence can be defined in terms of a spatial frequency. The Fourier transform characterises the rate of change of intensity along each dimension for an image. Most of the concepts from one dimension follow quite straight forwardly into two dimensions, such as transformations between time and frequency domains.

Fast Fourier transforms are used to multiply polynomials with

In order to multiply polynomials, we first need to represent them. Intuitively the most natural representation is

simply a sequence of the coefficients,

With coefficient representation, polynomial multiplication can be computed with time complexity

Given $n$ points $(x_i, y_i)$, with all distinct $x_i$, there is a unique polynomial $f(x)$ of degree-bound $n-1$ such that $y_k = f(x_k),\ \forall\ 0 \leq k < n$.

This means for a polynomial

With point-value representation, in order to do arithmetic its important that both the references use the

same evaulations points. If this holds for two polynomials of degree

To transform a polynomial of degree

To do this we consider the N-th complex roots of unity, given some

If

It follows from the halving lemma that if we square all the

So we want to evaluate a polynomial

This quite neatly outlines the recursive process used to compute the Fourier transform from coefficient form to

point-value form. As for the time complexity, to evaluate any given complex root of unity the problem is split into

exactly 2 subproblems of the same nature as the overall problem so it evidently has time complexity

As the FFT is a transformation from one representation to another, it naturally follows to think about the inverse

transformation, that is from point-value representation to coefficient representation. To compute the inverse FFT

with the same time complexity we use the following relationship,

$$

a_i = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=0}^{n-1}{y_i \omega_n^{-ji}}

$$

which from the FFT, switches the roles of

Convolution in the spatial domain is equivalent to multiplication in the frequency domain (and vice versa).

\begin{align*} g = fh &\implies G = FH \ g = fh &\implies G = FH \end{align*}

This derived as follows, \begin{align*} h(x) &= f(x) * g(x) = \sum_{y} f(x-y)g(y) \ H(u) &= \sum_x \Big( h(x) e^{-2\pi iux / N} \Big) \ &= \sum_x \Big( e^{-2\pi iux / N} \Big( \sum_{y} f(x-y)g(y) \Big) \Big) \ &= \sum_y \Big( g(y) \sum_x \Big( f(x-y) e^{-2\pi iux / N} \Big) \Big) \ &= \sum_y \Big( g(y) e^{-2\pi iuy / N} \sum_x \Big( f(x-y) e^{-2\pi iu(x-y) / N} \Big) \Big) \ &= F(u) \sum_y \Big( g(y) e^{-2\pi iuy / N} \Big) \ &= F(u) G(u) \ \end{align*}

Therefore using the Convolution Theorem in conjunction with the Fast-Fourier Transform the process of computing image responses to convolutions can be accelerated. The accelerated process has time complexity

The kernel for the Laplacian filter is $$ k = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 \ 1 & -4 & 1 \ 0 & 1 & 0 \ \end{bmatrix} $$

def laplace( img ):

img = np.float32( img )

kernel = np.matrix('0 1 0; 1 -4 1; 0 1 0')

return cv2.filter2D( img, -1, kernel )

def sharpen( img ):

return img - laplace( img )

img = load_image( 'lena.bmp' )

size = 20

kernel = np.zeros(( size, size ))

for i, j in indices( kernel ):

x, y = i - size/2, j - size/2

kernel[i, j] = gauss( 3, (0, 0), x, y )

img = cv2.filter2D( img, -1, kernel )

img = cv2.cvtColor( img, cv2.COLOR_BGR2GRAY )

laplaced = laplace( img )

sharpened = sharpen( img )

show_images([ img, laplaced, sharpened ],

['image', 'image*k', 'sharpened'],

figsize = (12, 10))This is the oldest gradient approximation kernel and is derived directly from the formulation that calculus uses to derive the differentiation operator.

Where

The Prewitt operator uses the assumption

Finally, the sobel operator improves on the Prewitt operator by assigning increased weight to pixels that are closer to the central pixel, i.e.,

def sobel( img ):

if len( img.shape ) == 3:

img = cv2.cvtColor( img, cv2.COLOR_BGR2GRAY )

gray = np.float32( img )

kx = np.matrix( '-1 0 1;-2 0 2;-1 0 1' )

ky = np.matrix( '-1 -2 -1;0 0 0;1 2 1' )

dfdx = cv2.filter2D( gray, -1, kx )

dfdy = cv2.filter2D( gray, -1, ky )

mag = np.hypot( dfdx, dfdy )

psi = np.arctan2( dfdy, dfdx )

return dfdx, dfdy, mag, psilena = load_image('lena.bmp')

show_images( map( to_255, list(sobel(lena)) ), figsize = (12, 6),

structure = [4],

titles = [ 'df/dx', 'df/dy',

'Magnitude Image', 'Gradient Image' ] )def gradient_vectors( image ):

dfdx, dfdy, mag, ang = sobel( image )

U = mag * np.cos( ang )

V = mag * np.sin( ang )

return U, V

def edge_vectors( image ):

dfdx, dfdy, mag, ang = sobel( image )

U = mag * np.cos( ang - np.pi / 2 )

V = mag * np.sin( ang - np.pi / 2 )

return U, V

def show_vectors_in_windows( U, V, image ):

x, y, w, h = 90, 150, 8, 8

U_win = U[ y:y+h, x:x+w ]

V_win = V[ y:y+h, x:x+w ]

win = image[ y:y+h, x:x+w ]

fig = plt.figure( figsize = (10, 10) )

ax = fig.add_subplot( 132 )

ax.set_title( 'Green window' )

show_image( win, ax, interpolation = 'none' )

ax.quiver( U_win, V_win, angles='xy' )

image_show_win = image.copy()

image_show_win = cv2.rectangle( image_show_win,

(x, y), (x+w, y+h),

(0, 255, 0), 2 )

x, y, w, h = 260, 260, 16, 16

U_win = U[ y:y+h, x:x+w ]

V_win = V[ y:y+h, x:x+w ]

win = image[ y:y+h, x:x+w ]

ax = fig.add_subplot( 133 )

ax.set_title( 'Red window' )

show_image( win, ax, interpolation = 'none' )

ax.quiver( U_win, V_win, angles='xy' )

lena_show_win = cv2.rectangle( image_show_win,

(x, y), (x+w, y+h),

(255, 0, 0), 2 )

ax = fig.add_subplot( 131 )

ax.set_title( 'lena.bmp' )

show_image( image_show_win, ax )

plt.show()U, V = gradient_vectors( lena )

show_vectors_in_windows( U, V, lena )U, V = edge_vectors( lena )

show_vectors_in_windows( U, V, lena )Given an image

The process of detecting shapes in images using Hough transforms is to find shapes that have values in the transform greater than some threshold. Rarely is one actually looking for perfect incarnations of a given shape in an image, however the Hough transform still provides indication of where shape-like features exist. In the situation where a perfect shape exists there would appear a sharp maxima at the exact point in the transform corresponding to the associated shape, as the shape becomes more imperfect this maxima becomes less and less sharp. Hence in order to detect non-perfect shapes the program instead needs too look for regions of high intensity in the transform and pick a single shape within the blob to represent the feature.

Lines are characteristic of two parameters; the

def draw_line( image, (r, phi) ):

''' Set all the points in an image along a

given linear equation to a value of 1. '''

newImage = np.zeros( image.shape )

transpose = phi < np.arctan2(*image.shape)

if transpose:

newImage = newImage.transpose()

for x, y in indices( newImage ):

if transpose:

newImage[x, y] = image[y, x]

else:

newImage[x, y] = image[x, y]

for x in range( newImage.shape[0] ):

y = int((r - x * np.sin(phi)) / np.cos(phi)) \

if transpose else \

int((r - x * np.cos(phi)) / np.sin(phi))

if 0 <= y < newImage.shape[1]:

newImage[x, y] = 1

return newImage.transpose() if transpose else newImage

def round_nearest( x, n ):

''' rounds x to the nearest multiple of n that is

less than x '''

return int(x / n) * n

def hough_line_transform( image, resolution ):

'''

Given an image with one colour channel and a set

of min, max, skip values to use as a resolution

of the Hough transform, this function returns a

matrix with votes corresponding to lines and a

function mapping entries in the Hough transform

to line parameters.

'''

r_min, r_max, p_min, p_max, r_skip, p_skip = resolution

w_H = 1 + int( (r_max - r_min) / r_skip )

h_H = 1 + int( (p_max - p_min) / p_skip )

hough = np.zeros((w_H, h_H))

greq_zero = partial( getitem, image )

for x, y in filter( greq_zero, indices( image ) ):

params =enumerate(np.arange( p_min, p_max, p_skip ))

for hy, p in params:

r = x * np.cos(p) + y * np.sin(p)

hx = round_nearest( r, r_skip ) - r_min

hough[ hx, hy ] += 1

return hough, lambda x, y : ((r_min + x * r_skip,

p_min + y * p_skip),

hough[ x, y ])

def accum_best( dist_fn, min_dist, thresh, acc, x ):

'''

A function to be partially applied and used in

a fold operation to extract parameters from a

parameter to vote mapping.

'''

p, v = x

if v < thresh: return acc

if acc == []: return [x]

pl, vl = acc[-1]

if dist_fn( pl, p ) > min_dist: return acc + [x]

if vl < v: return acc[:-1] + [x]

return acc

def hough_extract( hough_space, extract_fn, param_dist_fn,

thresh, min_dist ):

''' Extract shape parameters from a Hough transform

'''

items = list(starmap( extract_fn, indices( hough_space ) ))

items.sort( key = lambda x : param_dist_fn( (0, 0), x[0] ) )

accum = partial( accum_best, param_dist_fn, min_dist, thresh )

params_votes = reduce( accum, items, [] )

return [ p for p, v in params_votes ]The following generates an image with num_lines random lines drawn across it and computes the Hough space with a given resolution for the parameter search.

def demo_hough_lines( num_lines ):

shape = 100, 150

image = np.zeros(shape)

seed(0)

mag_space = range(max( *image.shape ))

mags = sample(mag_space, num_lines)

angle_space = np.linspace( -np.pi, np.pi,

5*num_lines )

angles = sample(angle_space, num_lines)

lines = zip(mags, angles)

image = reduce( draw_line, lines, image )

r_min, r_max = 0, int(np.hypot( *image.shape ))

p_min, p_max = 0, np.pi * 2

r_skip, p_skip = 1, 0.03

resolution = ( r_min, r_max,

p_min, p_max,

r_skip, p_skip )

image_lines, param_map = hough_line_transform( image, resolution )

def euclid( (x1, y1), (x2, y2) ):

return ( (x1 - x2)**2 + (y1 - y2)**2 )**0.5

lines_h = hough_extract( image_lines, param_map,

euclid, 20, 10 )

image_h = reduce( draw_line, lines_h, np.zeros(shape) )

image_c = np.zeros( image.shape + (3,) )

for x, y in indices( image ):

image_c[ x, y, 0 ] = image[x, y]

image_c[ x, y, 1 ] = image_h[x, y]

fig = plt.figure( figsize = (10, 10) )

ax = fig.add_subplot( 121 )

ax.set_title( 'Image domain' )

show_image( image_c, ax )

ax = fig.add_subplot( 122 )

ax.set_title( 'Hough transform' )

show_image( image_lines, ax )

plt.show()

for i in range( 1, 14 ):

demo_hough_lines( i )

clear_output( wait = True )In the left image above, the red lines represent the original lines generated at random and the green lines represent the lines derived from the Hough transform. The right image shows the Hough transform as an image, areas of brightness correspond to more pixels voting that the associated lines appear in the input image.

Run the cell above to see how the algorithm reacts to different arrangements. Tuning the min_dist and thresh values of the extracting parameters function also changes how many lines are detected.

Circles are shapes described by the two parametric equations

\begin{align*} x_0 &= x \pm \cos \nabla I_{x,y} \ y_0 &= y \pm \sin \nabla I_{x,y} \ \end{align*}

def hough_circle_space( img, r_min_p, r_max_p, t ):

'''

Params:

img - image to find circles within

rMinP - proportion of the major axis of the

image to use as the maximum radius

rMaxP - proportion of the major axis of the

image to use as the minimum radius

t - percentage of the maximum magnitude

to use as the thresholding value

'''

dfdx, dfdy, mag, psi = sobel( img )

def offset( val, offset ):

return ( int( val + offset ), int( val - offset ) )

def make_circle( point, radius ):

grad = psi[ point ]

xs = offset( point[1], radius * np.cos( grad ) )

ys = offset( point[0], radius * np.sin( grad ) )

return product( xs, ys, [ radius ] )

h, w = mag.shape

r_min = int( r_min_p * w )

r_max = int( r_max_p * w )

threshold = t * np.max( mag )

xs = xrange(w)

ys = xrange(h)

indices = ifilter( lambda p : mag[p] > threshold,

product( ys, xs ) )

points = product( indices,

xrange( r_min, r_max ) )

circles = chain.from_iterable( starmap( make_circle, points ) )

return Counter( circles )

def hough_circle_space_image( w, h, hough, r_min_p, r_max_p ):

r_min = int( r_min_p * w )

r_max = int( r_max_p * w )

hough_image = np.zeros(( h + 2*r_max, w + 2*r_max ))

for (x, y, r), v in hough.items():

hough_image[ y + r_max, x + r_max ] += v

return hough_image

def circles_from_hough( space, threshold_p ):

threshold = threshold_p * max( space.values() )

return [ k for k, v in space.items() if v > threshold ]

def highlight_circles( img, circles ):

highlighted = img.copy()

for (x, y, r) in circles:

cv2.circle( highlighted,

(x, y), r,

(0, 255, 0), 1 )

cv2.rectangle( highlighted,

(x - 2, y - 2), (x + 2, y + 2),

(0, 128, 255), -1 )

return highlightedcoins = load_image( 'coins1.png' )

thresh = int( 0.6 * 255 )

canny = cv2.Canny( coins, thresh, 255 )

blur = cv2.GaussianBlur( canny, (5, 5), 10 )

_, threshed = cv2.threshold( blur, 10, 255, cv2.THRESH_BINARY )

canny = cv2.Canny( threshed, thresh, 255 )

h, w = canny.shape

rMinP = 0.03

rMaxP = 0.15

t = 0.4

space = hough_circle_space( canny, rMinP, rMaxP, t )

hImg = hough_circle_space_image( w, h, space, rMinP, rMaxP )

circles = circles_from_hough( space, 0.8 )highlighted = highlight_circles( coins, circles )

show_images([ coins, canny, hImg, highlighted ])Image segmentation is the process of grouping spatially nearby pixels according to a given criteria. The benefit of such a process is reducing a potentially large number of pixels into fewer regions that are indicative of some interesting semantic relationship. Perfect image segmentation is difficult to achieve, there are several problems that present themselves.

The criteria provided may not be well-defined enough to uniquely categorize pixels, for example if the objective was to segment pixels based on either being leaves or not-leaves in the picture above there would be ambiguity in the blurry regions caused by lense focus. The effects of noise, non-uniform illumination, occlusions ect. result in the same issue. Over-segmentation is when multiple segments should belong to the same category. Under-segmentation is when when segments should really be broken down to into smaller independent regions. Under and over segmentation stems from not tuning the segmentation criteria correctly.

There are several common segmentation methods:

- Thresholding methods: pixels are categorized based on intensity.

- Edge-based methods: pixels are grouped by existing within edge boundaries.

- Region-based methods: pixels are grouped by growing regions from seed pixels.

- Clustering and Statistical methods: pixels are associated with a metric and methods such as k-means, Gaussian Mixture Models or hierarchical clustering is used to categorize pixels.

The threshold selection algorithm starts by computing an intensity value histogram for an image and selecting an initial estimate for some threshold

The general idea of edge-based methods is to run an edge detection algorithm and extend or delete the given edges.

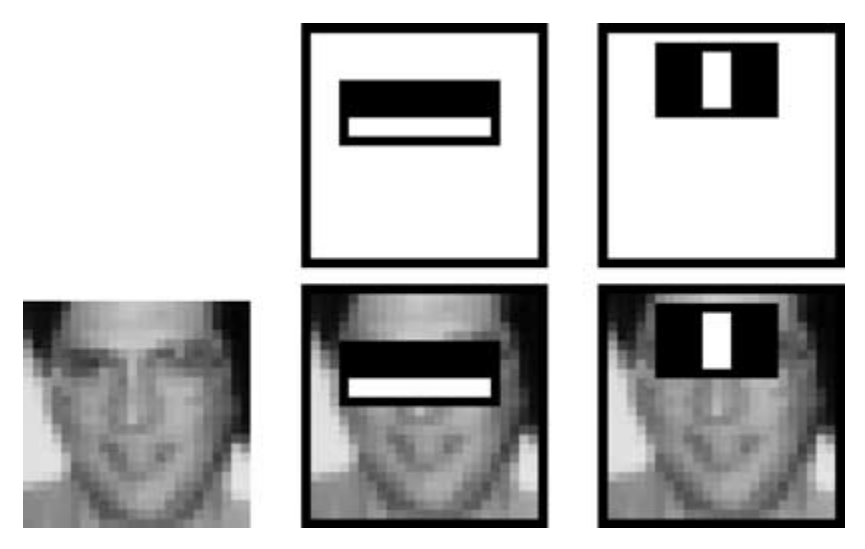

The method proposed by Viola and Jones (2005) brings together new algorithms and insights to construct a framework for robust and extremely rapid visual detection. The procedure uses the evaluation of simple "Harr-like" features that can be evaluated in constant time in any location or scale, these are then fed into a model learned using AdaBoosting. Finally the for real-time evaluation a method of combining successively more complex classifiers in a cascading fashion is used, where the intuition is that more complex classifiers are reserved for more promising regions.

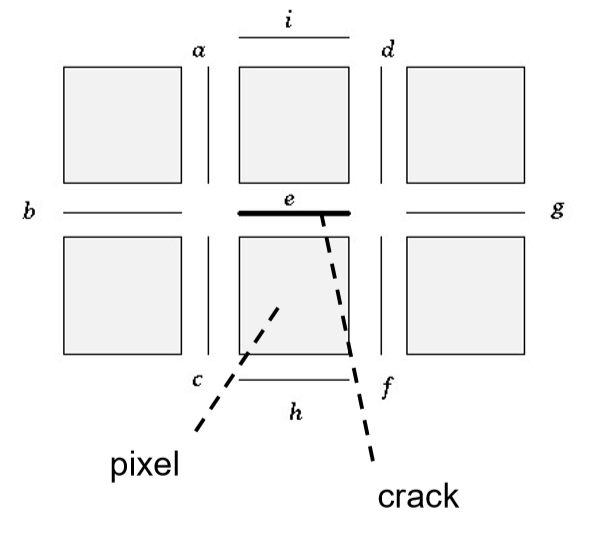

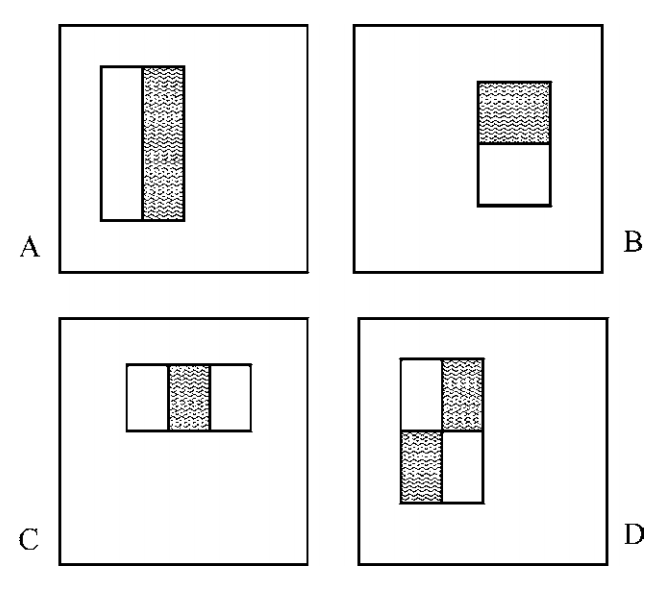

There are four types of Harr-like features, as demonstrated in the image below. The way these shapes become values is to take the sum of the values in the white regions and subtract the sum of the values in the grey regions.

These features can be so quickly computed by introducing the Integral image transformation. For a given image

\begin{align*} II_{x, y} = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } x < 0 \text{ or } y < 0 \ I_{x, y} + II_{x-1, y} + II_{x, y-1} - II_{x-1, y-1} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{align*}

By memoizing this,

Therefore given the definition of Harr-like features, they too can be computed in constant time.

def integral( image ):

if len( image.shape ) == 3:

image = cv2.cvtColor( image, cv2.COLOR_RGB2GRAY )

def ii( x, y ):

if x < 0 or y < 0:

return 0

return result[ x, y ]

result = np.zeros( image.shape )

for x, y in indices( image ):

result[ x, y ] = image[ x, y ] + ii( x - 1, y ) +\

ii( x, y - 1 ) - ii( x - 1, y - 1)

return result

lena = load_image( 'lena.bmp' )

lena_face = lena[ 200:400, 200:350 ]

integral_lena_face = integral( lena_face )

show_images([ lena_face, integral_lena_face ],

titles = ['input image', 'integral image'],

orientation = 'vertical', figsize=(3, 6) )def sum_rectangle( II, (x1, y1, x2, y2) ):

return II[ x2, y2 ] - II[ x1, y2 ] - II[ x2, y1 ] + II[ x1, y1 ]

rect = partial( sum_rectangle, integral(image) )Given a set of labelled instances

The following is two frames from a video with a small amount of motion, the image to the right highlights the movement between the frames by subtracting denoised-grayscaled versions from the frames from one another. This shows the head moving to the left by highlighting the parts of the image that have been moved into and leaving a shadow where the head was previously.

cap = cv2.VideoCapture('images/hand_wave.mp4')

def read():

_, frame = cap.read()

w, h, c = frame.shape

frame = cv2.resize( frame, (h // 6, w // 6) )

frame = cv2.cvtColor( frame, cv2.COLOR_BGR2RGB )

frame = cv2.transpose( frame )

return frame

for i in range(10):

read()

frames = [ read(), read() ]

w, h, c = frames[0].shape

frames = [ f[:h, :] for f in frames ]

cap.release()

def dIdt( frames ):

frames_denoised = map( cv2.fastNlMeansDenoisingColored, frames )

convert_gray = partial( cv2.cvtColor, code=cv2.COLOR_BGR2GRAY )

frames_gray = map( convert_gray, frames_denoised )

frames_f32 = map( np.float32, frames_gray )

return frames_f32[0] - frames_f32[1]

fig, axs = plt.subplots( 1, 3, figsize=(10, 10) )

I_t = dIdt( frames )

axs[-1].imshow( I_t, cmap='Greys_r' )

axs[-1].axis( 'off' )

axs[-1].set_title( 'dI/dt')

params = enumerate(zip( frames[:2], axs[:-1] ))

for i, (im, ax) in params:

ax.imshow( im, cmap='Greys_r' )

ax.axis('off')

ax.set_title( 'I_%i' % (i+1) )

plt.show()The Lucas-Kanade optical flow algorithm is a simple technique which can provide an estimate of the movement of structures in images. The method does not use color information in an explicit way. It does not scan the second image looking for a match for a given pixel. It works by trying to guess in which direction an object has moved so that local changes in intensity can be explained. The algorithm assumes the following,

-

Consecutive images are separated by a sufficiently small time increment

$\delta t$ relative to the movement of structures in the images. -

The images are relatively noise free.

For a single pixel

By considering a local window of

def lucas_kanade(im1, im2, win=2):

assert im1.shape == im2.shape

I_x = np.zeros(im1.shape)

I_y = np.zeros(im1.shape)

I_t = np.zeros(im1.shape)

I_x[1:-1, 1:-1] = (im1[1:-1, 2:] - im1[1:-1, :-2]) / 2

I_y[1:-1, 1:-1] = (im1[2:, 1:-1] - im1[:-2, 1:-1]) / 2

I_t[1:-1, 1:-1] = dIdt([im1, im2])[1:-1, 1:-1] #im1[1:-1, 1:-1] - im2[1:-1, 1:-1]

params = np.zeros(im1.shape + (5,)) #Ix2, Iy2, Ixy, Ixt, Iyt

params[..., 0] = I_x * I_x # I_x2

params[..., 1] = I_y * I_y # I_y2

params[..., 2] = I_x * I_y # I_xy

params[..., 3] = I_x * I_t # I_xt

params[..., 4] = I_y * I_t # I_yt

del I_x, I_y, I_t

cum_params = np.cumsum(np.cumsum(params, axis=0), axis=1)

del params

win_params = (cum_params[2 * win + 1:, 2 * win + 1:] -

cum_params[2 * win + 1:, :-1 - 2 * win] -

cum_params[:-1 - 2 * win, 2 * win + 1:] +

cum_params[:-1 - 2 * win, :-1 - 2 * win])

del cum_params

op_flow = np.zeros(im1.shape + (2,))

det = win_params[...,0] * win_params[..., 1] - win_params[..., 2]**2

op_flow_x = np.where(det != 0,

(win_params[..., 1] * win_params[..., 3] -

win_params[..., 2] * win_params[..., 4]) / det,

0)

op_flow_y = np.where(det != 0,

(win_params[..., 0] * win_params[..., 4] -

win_params[..., 2] * win_params[..., 3]) / det,

0)

op_flow[win + 1: -1 - win, win + 1: -1 - win, 0] = op_flow_x[:-1, :-1]

op_flow[win + 1: -1 - win, win + 1: -1 - win, 1] = op_flow_y[:-1, :-1]

return op_flownp.seterr('ignore')

fig, axs = plt.subplots( 1, 3, figsize = (12, 4) )

for win, ax in zip([5, 11, 15], axs):

motion_field = lucas_kanade_np( *frames_f32, win=win )

f1, f2 = frames

U, V = motion_field[ :, :, 0 ], motion_field[ :, :, 1 ]

w, h, c = f1.shape

shape = ( w // win, h // win )

params = np.zeros( shape + (5,) )

for i, j in product(*map(range, shape)):

ii, jj = win * i , win * j

params[i, j, 0] = ii + win // 2

params[i, j, 1] = jj + win // 2

params[i, j, 2] = U[ii, jj] / win

params[i, j, 3] = V[ii, jj] / win

ax.imshow( f1, interpolation = 'none' )

ax.axis('off')

ax.quiver( params[..., 1], params[..., 0],

params[..., 2], params[..., 3],

units='xy', color='g' )

axs[0].set_title( '5x5 window' )

axs[1].set_title( '11x11 window' )

axs[2].set_title( '15x15 window' )

plt.show()Scale-invariance is achieved by creating feature points from regions the lie on the extrema of the Difference of Gaussian tree for a given image. With the regions selected the dominant orientation is notated as a vector where the direction corresponds to the sum of the gradient vectors in the region and the magnitude is indicative of the size of the region. The vectors in the region are then projected onto unit vectors in eight directions from which a histogram is constructed. This histogram is the spatial gradient descriptor of the region, when looking for matches to this descriptor all the vectors in the target region are rotated by the cosine distance between the target's dominant vector and the original dominant vector. This normalizes the orientation and makes the transform invariant to rotation.

The image is blurred more and more, then the difference of consequetive images is taken.

def accum_blur( images ):

rest, tail = images[:-1], images[-1]

return rest + [ tail, cv2.GaussianBlur( tail, (5, 5), 10 ) ]

def DoG_tree( image, depth = 4, width = 8 ):

# layer = [ cv2.GaussianBlur( image, (i, i), 10 ) for i in range(11, 27, 2) ]

layer = reduce( lambda x, y : accum_blur(x), range( width - 1 ), [image] )

fig, axs = plt.subplots( 1, len(layer), figsize = (32, 32) )

for _ in starmap( show_image, zip( layer, axs )): pass

for _ in range( depth - 1 ):

layer = list(starmap( sub, zip( layer[1:], layer[:-1] ) ))

fig, axs = plt.subplots( 1, len(layer), figsize = (32, 32) )

for _ in starmap( show_image, zip( map( to_255, layer ), axs )): pass

image = load_image( 'table_things.jpg' )

image_gray = cv2.cvtColor( image, cv2.COLOR_RGB2GRAY )

DoG_tree( image_gray )gauss_image = np.zeros((16, 16))

mean = ( gauss_image.shape[0] / 2, gauss_image.shape[1] / 2 )

std = gauss_image.shape[0] / 5

G = partial( gauss, std, mean )

zs = starmap( G, indices( gauss_image ) )

for v, (i, j) in zip( zs, indices( gauss_image ) ):

gauss_image[ i, j ] = v

ax = show_image( gauss_image, interpolation = 'none' )

U, V = gradient_vectors( gauss_image )

ax.quiver( U, V, color='#00ff00', angles='xy' )

plt.show()def show_spatial_gradient_descriptor( image, window ):

x, y, w, h = window

win_image = image[ x:x+w, y:y+h ]

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(12, 4))

rgb = cv2.cvtColor( image, cv2.COLOR_GRAY2RGB )

highlighted = cv2.rectangle( rgb,

(y, x), (y+h, x+w),

(0, 255, 0), 2 )

show_image( highlighted, axs[0] )

axs[0].set_title( 'highlighting the window' )

show_image( win_image, axs[1], interpolation='none' )

U, V = gradient_vectors( win_image )

axs[1].quiver( U, V, color='#00ff00', angles='xy' )

axs[1].set_title( 'gradient vectors in window' )

angles = np.arctan2(V, U).flatten()

axs[2].hist( angles, 8, facecolor='green', alpha=0.75 )

axs[2].set_title( 'spatial gradient descriptor for window' )

axs[2].set_xlim([ -3.5, 3.5 ])

plt.show()image = load_image( 'table_things.jpg' )

image_gray = cv2.cvtColor( image, cv2.COLOR_RGB2GRAY )

denoised = cv2.fastNlMeansDenoising( image_gray )

window = (160, 280, 16, 16)

show_spatial_gradient_descriptor( denoised, window )

window = (300, 250, 16, 16)

show_spatial_gradient_descriptor( denoised, window )The first descriptor has more variation in the angles, hence is more distinctive and better for matching than the second descriptor.