This document is a translation of the original post in My blog (in Spanish). I'll explain what I consider the ideal architecture for an application. Unlike my previous, more objective posts, here I'll share my personal opinion and explain why I prefer this approach.

- 1. What is Core-Driven Architecture?

- 2. Separation of Responsibilities in a Core-Driven Architecture

- 3. Tests within a Core-Driven Architecture

I will be discussing within the context of a professional environment or large applications. If you just want to make a small script or a small functionality that does X, I wouldn't do it this way; for that, you just create a script.

But let’s get into it. I worked with several application architectures like like MVC, Clean, Vertical Slice, or Hexagonal. While I don't strictly adhere to a predefined architecture, I mix a bit of everything to work in a way that is comfortable for me, which, in the end, is what matters.

This architecture might resemble others by about 90%, but there are so many that it doesn’t make sense to argue about it. What matters isn't the name, which I made up while writing this post, but rather the concept.

What I strictly follow is the separation of responsibilities.

This means that within each application, I will have different layers, and each layer has a clear responsibility.

It’s a mix between Clean Architecture, Hexagonal, and Layered, because we have a layer where the business logic is the most important (Clean Architecture), we use dependencies through interfaces (ports and adapters from Hexagonal), and there’s the layer separation and inward direction as seen in Layered.

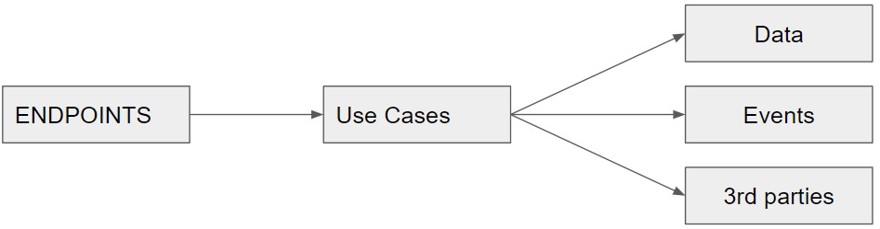

For example, in an API, we might have the following:

If you are working with C#, you can use folders or projects within a solution. Personally, I don’t mind as long as they are separated and have a clear division.

As we can see, we have an endpoint that only acts as a proxy between the call and the use case we are going to execute. The endpoint’s function is routing and checking authorization. It handles whatever is in the request pipeline, such as OpenAPI configuration; in summary, only elements related to being an API are present here.

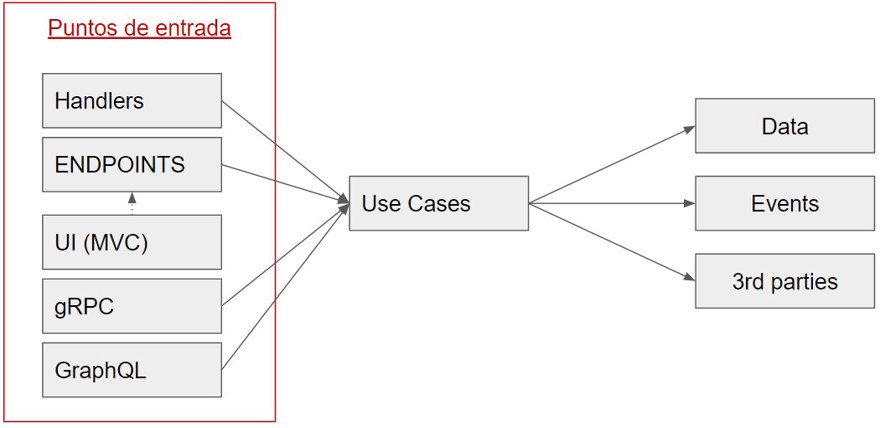

This means that if, instead of being an API, it’s a consumer of distributed architectures, the only change is that we won't have an endpoint launching the action, but rather a handler reading an event, verifying it hasn’t been processed, etc.

The same applies to the interface. If we use MVC, the interface may launch the call to the corresponding controller. What matters is that this layer is the entry point from the outside to our application and acts as such.

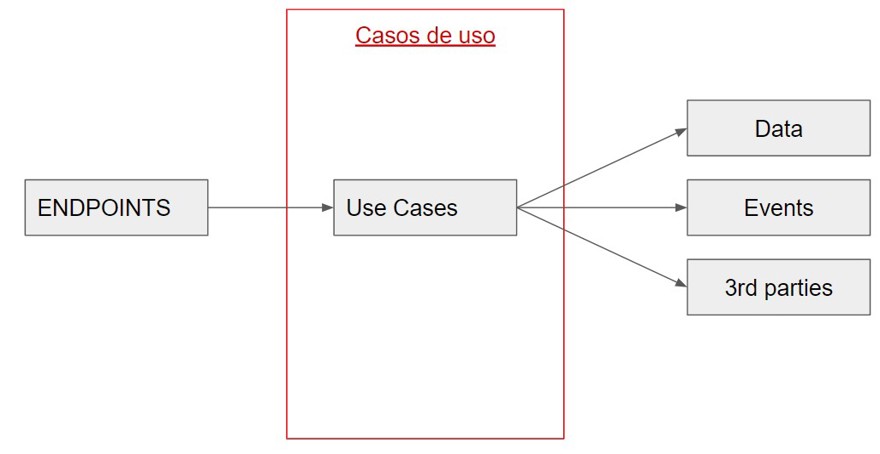

The intermediate layer is the most important because it contains the business logic layer, which is what we really need to test. This layer will perform all necessary checks and actions required by our use case.

For example, if we are creating clients in the database, we verify all the data, insert them, and as the final step, we publish an event indicating that an element has been created. All these actions happen within this use case.

For me, it’s important that this layer follows the Single Responsibility Principle. This means that each use case will perform a single action. Performing an action doesn’t refer to just validating or only inserting into the database; it refers to all the business rules required for something to happen.

This means that for creating a client, you will have one use case, and for updating a client, you will have a different one. In C#, this translates into several classes instead of one massive class doing many things.

This implies that, by the way we work, the API will comply with CQRS, separating reads from writes within our application.

Each use case contains everything needed to function. For example, if we are using the database, we inject it, whether it’s the DbContext or a repository if using the repository pattern or unit of work. If we are sending an event at the end of the process to notify that an element was created, we also inject the interface responsible for triggering these events:

public class AddVehicle(IDatabaseRepository databaseRepository,

IEventNotificator eventNotificator)

{

public async Task<Result<VehicleDto>> Execute(CreateVehicleRequest request)

{

VehicleEntity vehicleEntity = await databaseRepository.AddVehicle(request);

var dto = vehicleEntity.ToDto();

await eventNotificator.Notify(dto);

return dto;

}

}In this part, I use the same logic as Hexagonal Architecture with ports and adapters.

In this use case layer, many people who use Clean Architecture implement the mediator pattern. If you’ve read my post about Clean Architecture, you know my opinion on the mediator pattern: I personally don’t use it because it doesn’t add value, especially when used incorrectly (handlers calling other handlers). So, what I do is have one class per use case or action and then one class per “group” to encapsulate them:

public record class VehiclesUseCases(

AddVehicle AddVehicle,

GetVehicle GetVehicle);Even though the code is more coupled, I don’t see this as a bad thing since it's a microservice and there’s no issue.

Generally speaking, I don’t use interfaces in this layer, which means we inject concrete classes into the dependency container. The reason is simple: interfaces in this layer do not provide any value.

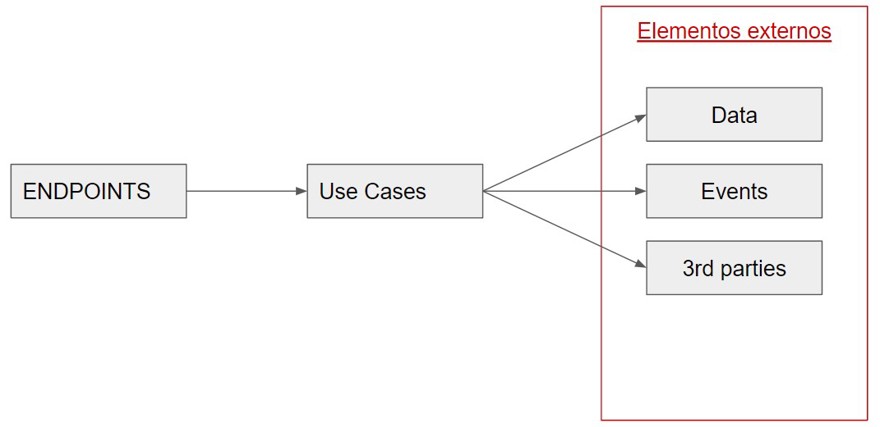

Finally, the last layer is where I define all the external elements of the application.

Here is where you’ll find reasons to use async/await since we will be communicating with external elements of the application.

In my particular workflow, I usually divide this layer into different projects within a single solution to have a clear separation. For example, I create a project called Data for everything related to the database. Whether I use the repository pattern or the DbContext, it will be located in this project, along with the database entities.

If I use RabbitMQ for event communication, all RabbitMQ configuration and implementation will be in that specific project.

As you can imagine, all access to different parts of the infrastructure or external services goes here. You can use either projects or folders, depending on how much you have and your personal preference or your organization’s standards.

This architecture heavily relies on Dependency Injection, as we will inject all elements into the upper layers.

For example, I inject the use cases into the controller and the database into the use cases. So far, everything is normal, but what I also do is declare all the elements that need to be injected within the project where they are defined.

This means that within my use case project, I have a static class with a single public method called AddUseCases,

but I also have a private method for each group of elements to be injected. This is the result:

public static class UseCasesDependencyInjection

{

public static IServiceCollection AddUseCases(this IServiceCollection services)

=> services.AddVehicleUseCases();

private static IServiceCollection AddVehicleUseCases(this IServiceCollection services)

=> services.AddScoped<VehiclesUseCases>()

.AddScoped<AddVehicle>()

.AddScoped<GetVehicle>();

}In Program.cs, this is called like so:

builder.Services

.AddUseCases()

.AddData()

.AddNotificator();In the upper layer (API), we simply invoke this AddUseCases.

Something to consider here: this configuration is simplified to improve the speed and ease with which we work with dependencies. Five years ago, when I started with the web, I created a library on GitHub and NuGet that allows you to indicate in the dependency project which modules you will need, and it checks if they are already injected. If not, it fails. The idea is good and it works (at least up to .NET 5), but I don’t think it’s worth it.

Although you could do something like this:

var serviceProvider = new ServiceCollection()

.ApplyModule(UseCases.DiModule)

.ApplyModule(Database.DiModule)

.BuildServiceProvider();What I do now is evolve towards simplicity.

As a final point, I will include certain preferences I have regarding how I build applications.

Personally, I have been using the Result pattern for more than five years, even though it has recently become trendy. The reason I like it is because it allows me to have an object that contains two states—success and error. Then, in the API, I can map it to a ProblemDetails with the correct HTTP status code.

Unless the application is very small, I always use standard controllers, not minimal APIs. This is because for creating APIs that are compatible with OpenAPI, it is much better. I will cover this more extensively in a future post.

Use cases will always return a DTO that can be safely sent outside the application. Within use cases, you can use entities, but never return an entity from a use case. This is the difference between a DTO and an entity. Lastly, I keep my DTOs in a separate project, so I can create a NuGet package if needed.

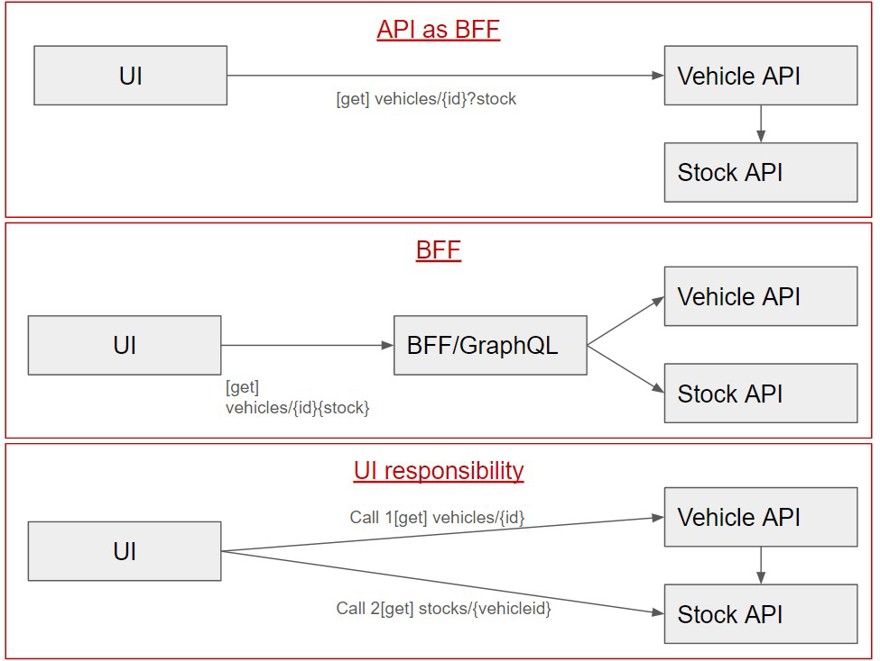

All APIs should not be Backend For Frontend (BFF), understanding BFF as an API that receives a request and returns all the necessary information. For example, let’s say we have a vehicle API where we create vehicle properties like brand, doors, color, etc.

The number of vehicles in stock is part of the inventory service, not the vehicle API. Therefore, if the user interface wants to display the number of available vehicles along with their details, we have several options:

- Call the inventory API from within the vehicle API to check how many are available.

- Create a BFF application that will aggregate the information from both services (or use GraphQL federated).

- Have the UI make both calls independently.

In my view, stock information does not belong to our vehicle API’s domain, so the first option should not be valid. Whether you choose option two or three depends on the user experience you want to offer.

When we use CQRS to separate reads from writes, it doesn’t mean we are only querying the database.

The separation is from the perspective of the consumer of the use case.

If we call GetVehicle, we will return a vehicle; we will not make any modifications to the database. It’s common sense.

You might be thinking that tests are not part of an application’s architecture or whatever you may believe.

However, the truth is that tests are necessary, so I wanted to include a small section on this. Ideally, we should cover all types of tests and have everything tested, etc. This isn’t always realistic or possible. But, thanks to how our application is designed, it is very easy to test our use cases, which are the core of our application.

As you may have noticed throughout this post, each use case has a single entry point, meaning that we will only have one method to test.

This doesn’t mean we should write only one test. Instead, we should have one test for each possible outcome of the use case.

If we are using exceptions for validation, we should validate those exceptions. If we are using Result<T>, we must validate each possible result.

Here’s an example of testing the AddVehicle use case:

public class AddVehicleTests

{

private class TestState

{

public Mock<IDatabaseRepository> DatabaseRepository { get; set; }

public AddVehicle Subject { get; set; }

public Mock<IEventNotificator> EventNotificator { get; set; }

public TestState()

{

DatabaseRepository = new Mock<IDatabaseRepository>();

EventNotificator = new Mock<IEventNotificator>();

Subject = new AddVehicle(DatabaseRepository.Object, EventNotificator.Object);

}

}

[Fact]

public async Task WhenVehicleRequestHasCorrectData_thenInserted()

{

TestState state = new();

string make = "opel";

string name = "vehicle1";

int id = 1;

state.DatabaseRepository.Setup(x => x

.AddVehicle(It.IsAny<CreateVehicleRequest>()))

.ReturnsAsync(new VehicleEntity() { Id = id, Make = make, Name = name });

var result = await state.Subject

.Execute(new CreateVehicleRequest() { Make = make, Name = name });

Assert.True(result.Success);

Assert.Equal(make, result.Value.Make);

Assert.Equal(id, result.Value.Id);

Assert.Equal(name, result.Value.Name);

state.EventNotificator.Verify(a =>

a.Notify(result.Value), Times.Once);

}

}While it’s important to test every possible outcome, the most important thing is to test the happy path, which is the path the code will follow when everything works as expected.

As you can see, I use Moq as my mocking library, though there are other alternatives available.

I also tend to create a class that acts as a “base” for the happy path and contains the dependencies that will be used.

Each test then describes in its name what it does and what it validates.