State machines are a way of modeling event driven systems to allow reasoning and analysis of their behaviours and properties.

Read and follow this README - throughout we will reference the code in the various subdirectories.

These programs are all writing in Rust or C. It's not necessary to run the tests to value from this - reading the code is sufficient.

If you want to run the tests however, all examples are managed by cargo (even the C examples). Please follow your platforms guide for "rustup" to setup a compatible environment. Once you have Rust working, you can run the tests in each subfolder with:

cd <name>

cargo test

An example is:

cd rust_microwave_simple

cargo test

An event driven system is a way of modeling a program or system so that it only acts on events that it recieves. By understanding all possible events that could occur in the system we can define well know states of the system that it can move between. We call these state machines, or formally, finite state automata.

As a result, these state machines by understanding all possible events, are exhaustive - we can account for and handle all possible inputs and actions in our system.

Microwaves are a common household device, that are intended to reheat food. This is achieved by directing electromagnetic waves into the food to cause vibration (aka heat) to be transfered. Because of this, microwaves have the capability to do great harm to a human or living being. The same waves that heat our food would literally cook our flesh. This makes microwaves a device with high safety requirements. Yet for a device that has the capability to perform great harm, they are common around the world.

To understand how microwaves have been made safe, we have to appreciate how they are built. If you feel like it, go and try and fill in the LANG_microwave_diy example now before we go on, and see how you go with your usual approach to programming.

git branch my_first_microwave

cd c_microwave_diy OR cd rust_microwave_diy

cargo test

# Once complete

git commit -a -m 'I did it?'

git checkout master

Remember this test framework is checking the outputs of the system - namely, the door, the time and the magnetron. It's up to your code to manage these values and emit them correctly as outputs depending on your programs state!

How did that go? Was it hard? Did you have a lot of issues with the tests? You can see how I did in rust_microwave_spaghetti - my first attempt. It's worth reading the comments because I had some amazing bugs that would have hurt people!

So how do we make a microwave safe? We need to understand them as event driven systems, with defined safe states. Some of these important safety properties include:

- If you press start and the door is open, it won't activate.

- If it's running and you open the door, it stops.

- The timer counts down, and then stops the microwave at 0 (overcooked food can cause fire, which is not conducive to living).

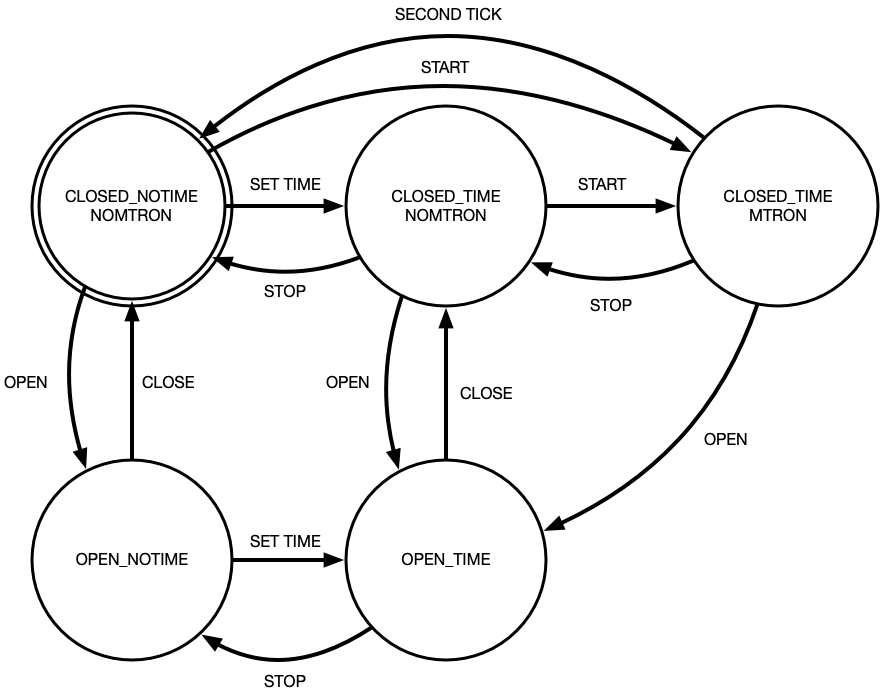

To really get a hold of this, we need to model this state machine. What are the safe and defined states the microwave can be in? What states should exist that help a user to interact with the system?

- Open door, with no time set (OPEN_NOTIME)

- Open door, with a time set (OPEN_TIME)

- Closed door, no time set, not running (CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON)

- Closed door, time set, not running (CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON)

- Closed door, time set, running (CLOSED_TIME_MTRON)

So those are our states - Notice there is no "open door + running" state! What about the possible events or inputs that can exist? How can a microwave be interacted with?

- open the door

- close the door

- set time

- press stop

- press start

- one second elapses

Now we need to examine each state and what valid transitions occur. We can arrange this in a table, of each possible input to each state, and what state that would result in. (There are more formalised definitions of this process, but I'm not here to lecture or formal systems, as much as practical state machine design).

So here's a table for you to fill in and have a go (You may need to copy it from the README.md into a different document to fill it in).

HINT: there may be two possibilities for CLOSED_TIME_MTRON on "one second".

| | OPEN_NOTIME | OPEN_TIME | CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON |

| open door | | | | | |

| close door | | | | | |

| set time | | | | | |

| stop | | | | | |

| start | | | | | |

| one second | | | | | |

How did you go? Here's my answer below. There are a few subtle behaviours in here too around the handling of the stop button and time setting.

The main complexity here is second counting with the CLOSED_TIME_MTRON state - if the time reaches zero we move to "notime" otherwise, we stay in CLOSED_TIME_MTRON. (Technically I think this make it a DFA with mealy machine properties).

| | OPEN_NOTIME | OPEN_TIME | CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON |

| open door | OPEN_NOTIME | OPEN_TIME | OPEN_NOTIME | OPEN_TIME | OPEN_TIME |

| close door | CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON |

| set time | OPEN_TIME | OPEN_TIME | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON |

| stop | OPEN_NOTIME | OPEN_NOTIME | CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON |

| start | OPEN_NOTIME | OPEN_TIME | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON |

| one second | OPEN_NOTIME | OPEN_TIME | CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON OR CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON |

To make it a bit clearer, lets blank the rows where the same state is remained in to help you see when events cause a change in state to occur (rather than remaining in the same state).

| | OPEN_NOTIME | OPEN_TIME | CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON |

| open door | - | - | OPEN_NOTIME | OPEN_TIME | OPEN_TIME |

| close door | CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON | - | - | - |

| set time | OPEN_TIME | - | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON | - | - |

| stop | - | OPEN_NOTIME | - | CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON | CLOSED_TIME_NOMTRON |

| start | - | - | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON | - |

| one second | - | - | - | - | CLOSED_TIME_MTRON OR CLOSED_NOTIME_NOMTRON |

That's a bit easier. Now we can see where the events will change our state rather that leaving us in the same state.

From this we can draw a pretty picture:

What's important is every input, at every state is well defined with a known safe or expected behaviour. This not only helps us to design the software but to design a series of test cases that will exercise or stress this model to ensure it is correct.

Now that we know our states, we can define these - enums are a great choice here because they then allow us to use match or case/switch on the values. For example (from rust_microwave_simple):

enum MicrowaveState {

OpenNoTime,

OpenTime(usize),

ClosedNoTimeNoMtron,

ClosedTimeNoMtron(usize),

ClosedTimeMtron(usize),

}

As events occur, we only need to change the value of self.state to a new enum value to progress through the machine.

There are three outputs in our system

- The door open

- The magnetron

- The time remaining

With the above states above, we can now map each state to a set of these outputs. IE OPEN_TIME would

yield { door_open: true, magnetron: false, time: X }.

When we poll the system, instead of having to store these "values" we just do a match or case/switch on the state, and yield the correct output that must exist given these states. Much easier than storing these booleans and remembering to toggle them all the time!

To remind you the test framework is just checking these three outputs, and providing the input actions. It has no knowledge of your state machine and how that drives the outputs you need to yield.

Feeling inspired? Ready to give it a go?

Just fill in the blanks in "rust_microwave_diy" to practice your new state machine designing skills!

If you want to try the C version, fill in "c_microwave_diy" to try out how you design state machines in C!

git branch my_good_microwave

cd c_microwave_diy OR cd rust_microwave_diy

cargo test

# Once complete

git commit -a -m 'I did it!!!'

git checkout master

rust_microwave_diy correlates to rust_microwave_simple, and c_microwave_diy correlates to c_microwave_simple if you would like to view my implementation.

So far we have talked about state machines as they exist at run time. A dynamic system that has to respond to all inputs and outputs, that could occur at anytime.

But we can also define state machines that exist in our code for compile time checks - where our code becomes the input and the output is a resulting program with defined workflows. A great example of this is a database. You take untrusted input, you normalise it, check it against schema, then you commit it to a backend. When you load that data you get the commited and valid entry, you need to invalid it, alter it, and re-check against the schema before you commit.

In this way Rust through it's generic system allows you to have compile time state machines. While it's inflexible for something as interactive as a microwave, you can see an example of how this works in rust_microwave_typed. It's also used extensively in Kanidm

The great benefit of this type of compiled machine is that invalid inputs are impossible to compile, and the strong type signatures mean that you can't send items in the wrong state to other functions.

An example could be here that the microwave as manufactured has the door open, but to be packed in a box must be closed. The packing function could be:

fn pack_mwave(mwave: Microwave<ClosedNoTimeNoMtron>) -> Result<..., ...> {

}

If you attempted to compile code like:

let mw: Microwave<OpenNoTime> = Microwave { state: OpenNoTime };

pack_mwave(mw).unwrap();

It would not compile because your microwave is in the wrong state - it can't be accepted! Because this is a compile time check rather than a run time one, it's very fast, and helps you to write better code that has models enforced at development time, rather than allowing mistakes to slip into run time.

Congratulations! You made it to the end.

From here you could start to think about your own programs, and how they can be improved with state machines. You'll hopefully start to notice them in programs all around you - TCP, BGP, Authentication, databases, and more.

If you have any questions, please get in touch!