MNKGames

- MNKGames

- Conclusion

- References

Summary

We used a heuristic Minimax algorithm with alpha-beta pruning for resolution of mnkgames, a generalized form of tic-tac-toe. The algorithm uses the evaluation heuristic to find out the order of exploration of a limited number of nodes and explores them to a predetermined depth level afterwards which returns a heuristic value, if the board is not terminal, or a final value, if the board is terminal.

From tests done locally, the algorithm appears to have similar or superior capabilities to that of a human for tables accessible to human limits (i.e. less than ~ 15).

Introduction

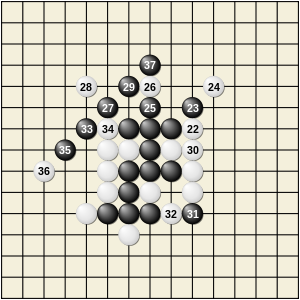

The proposed game is a generalized version of the tic-tac-toe game, or gomoku in Japan: a two-player game in alternating turns on a similar board as in the image, in which a certain number of pieces of one's own must be aligned player in order to win.

Following the characterization of a game environment by Russel and Norvig $^1$ we can describe the game as a deterministic, multiplayer environment with comprehensive information, sequential, static, known and discreet. This description allowed us to have one first idea of which algorithms could be used to solve the game, in how much in the literature this problem, and similar problems, have been solved with techniques that we can now consider classic.

Under this logic we have chosen the implementation of a minimax heuristic.

The high-level algorithm

Our minimax heuristic algorithm makes an initial estimate of how much it can explore, then uses a heuristic to decide the order of scanning of a limited number of moves. The latter will be visited in a limited number of nodes, determined by two constants that respectively indicate the number of nodes to expand in breadth and depth of exploration.

Topics covered

This high level details of the topics we cover in this document

- Faster and cache-friendly version to score the cells as marked and to cancel what is marked

- Explanation, calculation and use of heuristics for our minimax

- On the algorithm used to sort the moves according to of the value returned by the heuristic

- On the algorithm used to get an estimate of the quantity of explorable nodes

- On the methods of allocating a precise number of moves to the cells chosen for exploration

- On the choice of branching and depth values

- On the temporal and spatial complexity of the algorithm

Markcell and unmarkCell

Problem

Mark and unmark cells as quickly as possible.

Algorithms considered

-

Reallocation to each explorer node an array with the

freeCellminus the one just marked (in the case of markCell), or create an array with all thefreeCellsincluding the last move performed (in the case of unmarkCell), cost$O (n)$ -

use of a linked list that contains free cells. This approach despite having the constant-time insert and remove operations performed worse than reallocating an array at each explorer node (which cost $O (n)$) (we think this is due to array cache optimizations)

-

use of hashset: it has a linear cost in the bad case as well as very high constants in the average case.

Algorithm used

We have devised a system that is able to perform the operations of markCell, unmarkCell in constant time

in the best, worst and average case, without considering the additional checks to verify the status

of the game and the updating of the heuristics.

In order to achieve this speed, the set of moves performed is kept at the end of an array that contains all the moves, similar to what a heap does at the time of removal.

As the cells are used, it swaps with the last cell in the array marked as free e

it memorizes the position it was in, by doing so, when the unmarkCell is called, it manages to reposition itself in its old position.

This implementation improves upon the initial code board

in the worst case, as it no longer needs a hashtable, whose worst case is

to the size of the table.

Note: all cells contain an index which indicates the position of the array in which the move is contained, otherwise, if this has not yet been removed, it indicates the return position.

The heuristics

In this project the heuristics used for the Player's success are fundamental. There is a single heuristic that is used, in different ways, for both board evaluation both for the choice of moves.

What does it represent

The heuristic used gives me an importance value of the single cell for both me and my opponent.

The sum of the two values of importance gives me an estimate of the criticality of the single cell.

With this numerical value it is possible to order the moves according to an order of priority.

This heuristic is a modified version of the heuristic proposed by Nathaniel Hayes and Teig Loge $^ 3$ adapted for board size

greater than 3x3 or 4x4, together with a modified version of the Chua Hock Chuan $^4$ heuristic, for evaluation

of critical alignments of K - 1 and K - 2.

Computing heuristics with sliding windows

We define ** Sliding-window ** a set of cells aligned in a direction of length

K

The heuristic calculates the following values for each direction of a single cell and for both players:

- The number of friendly cells present

- The number of sliding windows that pass through a cell

- Maximum number of sliding windows with fewer cells needed for victory

- The number of maximum sliding windows

To do this we update all cells in the 4 possible directions up to a maximum distance K,

and we are going to update the values in of these cells in the direction through which they align with the modified cell.

To refresh these values we call the updateDirectionValue function.

The function that updates a single cell for one direction is implemented in computeCellDirectionValue.

This function scans the current cell, either horizontally or vertically, and widens as far as it can go

one direction (at most K - 1), once the limit is reached in this direction, expands in the opposite direction, keeping

the sliding window in case it has been created. While it also expands to the other side, until it goes beyond the k-1 cells or until it finds a cell of the other player,

it updates the values of the current sliding window, and updates the values of the cell being updated.

Detection of double-games and end-of-games

With the sliding window system we can also very easily detect some * critical * cells that is situations of double games or games with one move from the end.

We define end-game cells for which there is at least one sliding window that has 1 move left to win

It is clear that these cells are very important both for us, for the purpose of victory, and for the enemy, for the purpose of blocking.

We define double-games the cells for which there are two or more sliding windows for which 2 moves are missing to win

If we have such a configuration, it can be seen how moving to that cell reduces the moves to win of 1 in both sliding windows. We then have two sliding windows in which one move is missing to win, so the enemy it can block at most one, guaranteeing us victory over the other.

Regarding non-trivial double games, i.e. double games in which we need 3 or more moves to win, we rely on ability of the minimax to find them, we could not find a way to code this case through sliding-windows.

Scores for double-game and end-game configurations

Some special scores are assigned to double-game or end-game cells.

These configurations are not explicitly visible from the heuristics inspired by Nathaniel Hayes and Teig Loge, so we have assigned fixed values to * steps *, that is, in whatever way the previously named heuristic is calculated, the heuristic value calculated by the latter cannot exceed the value assigned by a double game cell, and the latter cannot exceed the value of an end game cell.

So in order of importance we have:

-

End-of-game cell

-

Trivial double-game cell

-

Cell evaluated by Nathaniel Hayes and Teig Loge heuristic + alignment and proximity scores.

Scores for alignment and proximity

With empirical evidence we have noticed that heuristics as explained so far are unable to evaluate some alignment situations correctly, so we added score multipliers for cell alignment and to favor moves close to some already aligned cells.

You can see the values of these multipliers MY_CELL_MULT and ADIACENT_MULT respectively in the `DirectionV file

alueandHeuristicCell`.

These values were found to be fundamental for the player's intelligent game.

Order of moves

Problem

At any time from the board we need to find the best q cells sorted in such a way

descending, which will determine the search order.

On an array of n free cells, we need to sort the first qs that have the highest value

Approaches considered

-

The first normal sorting that went to

$O (n , \ log , n)$ where n are free cells -

Quick select, which correctly separates the larger

qelements, but does not sort them. This would have cost$O (n + q , \ log , q)$ in the middle case e and worst execution time, however, would have been$O (n ^ 2 + q , \ log , q)$ where$O (n ^ 2)$ in the worst case of quick-select and$O (q , \ log , q)$ to sort the cells.

Algorithm used

The method we used uses a slight variation of the heap-select algorithm:

it goes through the array of free cells keeping a heap of maximum q elements of it, and finally

empties the heap and puts it into an array that contains the first sorted q cells.

Computational cost

This improvement on the first tests resulted in exploring the board 5 or 6 times more moves with the same input time.

An example of using this algorithm can be found in the Board's updateCellDataStruct. In this case we use

the branchingFactor variable to keep the value of q very low.

Timer Test

Problem

In order to use all the computational time available there was a need to find a method that allowed to explore interesting nodes making the most of the time available.

Proven approaches

- A timeout check on each node of the minimax: this approach did not work because there was a risk that at the first level few nodes were explored, due to deep exploration.

- Exploration of a part of the tree of predetermined width and depth: this approach carried the risk of tuning depth and width parameters, which could change depending on the computer.

Solution used

Eventually we used ideas from both methods, creating a simulation of the decision process that he explored as many nodes as possible and give an estimate of how many it was possible to visit, always maintaining the depth and width constants set for the various types of boards.

In order to have an estimate of how many search nodes any computer could process with a fixed time limit we have

we use the TimingPlayer class, which simulates the decision process of our algorithm,

taking into account how many nodes he managed to visit by the end of the allotted time.

Splitting and using the number of moves

Problem

We would like the more promising cells to have more time to explore. We need to create a method to distribute the number of moves available while exploring the minimax.

Solution used

We have seen that following sorting with heuristics, the first cells are the most important ones to explore, as it favors the pruning of other search nodes thanks to alpha-beta pruning. So we want to distribute more moves to the first cell, so that it can have a deeper exploration and a higher probability of pruning.

In findBestMove we see how the number of cells found are used like this:

In the event that the first cell does not use all the given cells, these will be entrusted to the subsequent exploration cells.

The next exploration cell can, therefore, scan a number of cells equal to the number of previous unused nodes + adding new cells to explore.

So for the first branchingFactor * 3 with the largest heuristic values.

Choice of branching factor and depth

Problem

The branching and depth factors have a direct impact on the execution time of the algorithm, and on the quality of the chosen move. It was therefore very important to find the correct values to assign for each board.

Solution used

We were aware of the possibility of using machine learning methods in order to find in these values.

However, we were not aware of the application methods in our environment, nor whether the values could depend on the computer on which the program was run.

We therefore decided to use some fixed values, which we found based on empirical evidence.

Cost analysis

In this section we present a step-by-step computational cost analysis of our algorithm.

markCell and unmarkCell

Both the mark and the unmarkCell must first update the free cells, which both functions do in

So mark and unmark cell have a computation cost of

minPlayer and maxPlayer

These two methods are the players of the minimax, respectively the minimum and maximum players.

Each of these performs operations that depend on the cost of markCell and unmarkCell, and on BRANCHING_FACTOR and DEPTH which are constant.

So let $ C (k) $ be the cost of markCell and unmarkCell, these operations are performed at each node up to the fixed depth. It costs $ (C (k) \ cdot branchingFactor) ^ {DEPTH - depthReading} $ for these two algorithms in the worst case all nodes are visited and pruning is never performed.

SelectCell and findBestMove

SelectCell first calls findBestMove to find the best move.

findBestMove performs constant operations and calls updateCellDataStruct which reorders the cells

in

findBestMove reorder moves in through the heuristic and call the minimax with

alpha beta pruning in order on those that have a higher value.

The cost of this algorithm is

the worst case minPlayer cost is

The cost of both markCell and unmarkCell in the worst case is

So the worst case cost of our algorithm is

If we consider branchingFactor as a constant, then we have that cost in the worst case

is

Analysis of the cost in memory

Our algorithm is very space efficient:

The only objects that are stored are the HeuristicCells which always remain the same for an entire game, never being destroyed or recreated.

in the middle.

At the beginning of the game, a number of cells equal to $ MN $ are created and stored in 3 different data structures of size $ MN $.

Respectively they are:

-

Board, which contains all the cells in a two-dimensional array of size $ M \ cdot N $. -

allCells, which contains the same cells in a one-dimensional array of size $ MN $. This array is used for markCell and unmarkCell -

sortedAllCells, which contains a portion of the cells sorted by heuristic. This array is used to decide on a scan order.

During the exploration with the minimax, the board is never recreated, but is modified and restored with each move, guaranteeing great efficiency in

memory terms.

During this exploration, call frames are added to the program stack, which slightly affect the space cost. But being the

DEPTH a constant value, this contribution could be considered irrelevant compared to the rest.

So we can say that the cost in memory is

Failure approaches

-

Monte Carlo simulation (MCTS), which we have tried given the great success of AlphaGo

- He looked at cells that had little value for victory

- He looked at all the states at each level, which also weighed heavily on his memory (as he kept the whole game tree)

- The time limit was too low to have enough simulations

- The capability of the hardware greatly affected the results.

-

Pure heuristic algorithm (also known as Greedy best first Search)

- He couldn't go deep, as he selected the cell most likely to each time victory at the first level, this did not allow him to plan his moves.

-

pure alpha beta pruning, for large tests it took too long to execute, unable to eval even a move

-

rule-based strategy $^ 2$, based on 5 steps that I report here verbatim: Rule 1 If the player has a winning move, take it. Rule 2 If the opponent has a winning move, block it. Rule 3 If the player can create a fork (two winning ways) after this move, take it. Rule 4 Do not let the opponent create a fork after the player's move. Rule 5 Move in a way such as the player may win the most number of possible ways.

- These rules were very important as a guide to our project, although they are not explicitly applied, they drove the fixed value for the double-game and end-game cells.

-

Iterative Deepening, such as alpha-beta pruning was unable to explore enough of the search tree.

Possible improvements

- Use a machine learning system to decide the

BRANCHING_FACTORandDEPTH_LIMITwhich are now of fixed values, according to human experience. - Use multiple threads for parallel exploration of the search tree (not possible due to imposed limits).

- Update of the heuristic in

$O (k)$ instead of the current$O (k ^ 2)$ , where$k$ is the number of cells to align.

Conclusion

We have observed how a classic Minimax algorithm with alpha-beta pruning can play similarly, or better compared to an average human player for boards of adequate size for the human, given a heuristic that allow to prune wide tree branches.

References

-

Russell, Stuart J., and Peter Norvig. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. Fourth edition, Global edition, Pearson, 2022.

-

Development of Tic-Tac-Toe Game Using Heuristic Search IOP Publishing, 2nd Joint Conference on Green Engineering Technology & Applied Computing 2020, Zain AM, Chai CW, Goh CC, Lim BJ, Low CJ, Tan SJ

-

Developing a Memory Efficient Algorithm for Playing m, n, k Games, Nathaniel Hayes and Teig Loge, 2016.

-

Chua Hock Chuan, Java games, https://www3.ntu.edu.sg/home/ehchua/programming/java/JavaGame_TicTacToe_AI.html, 2017