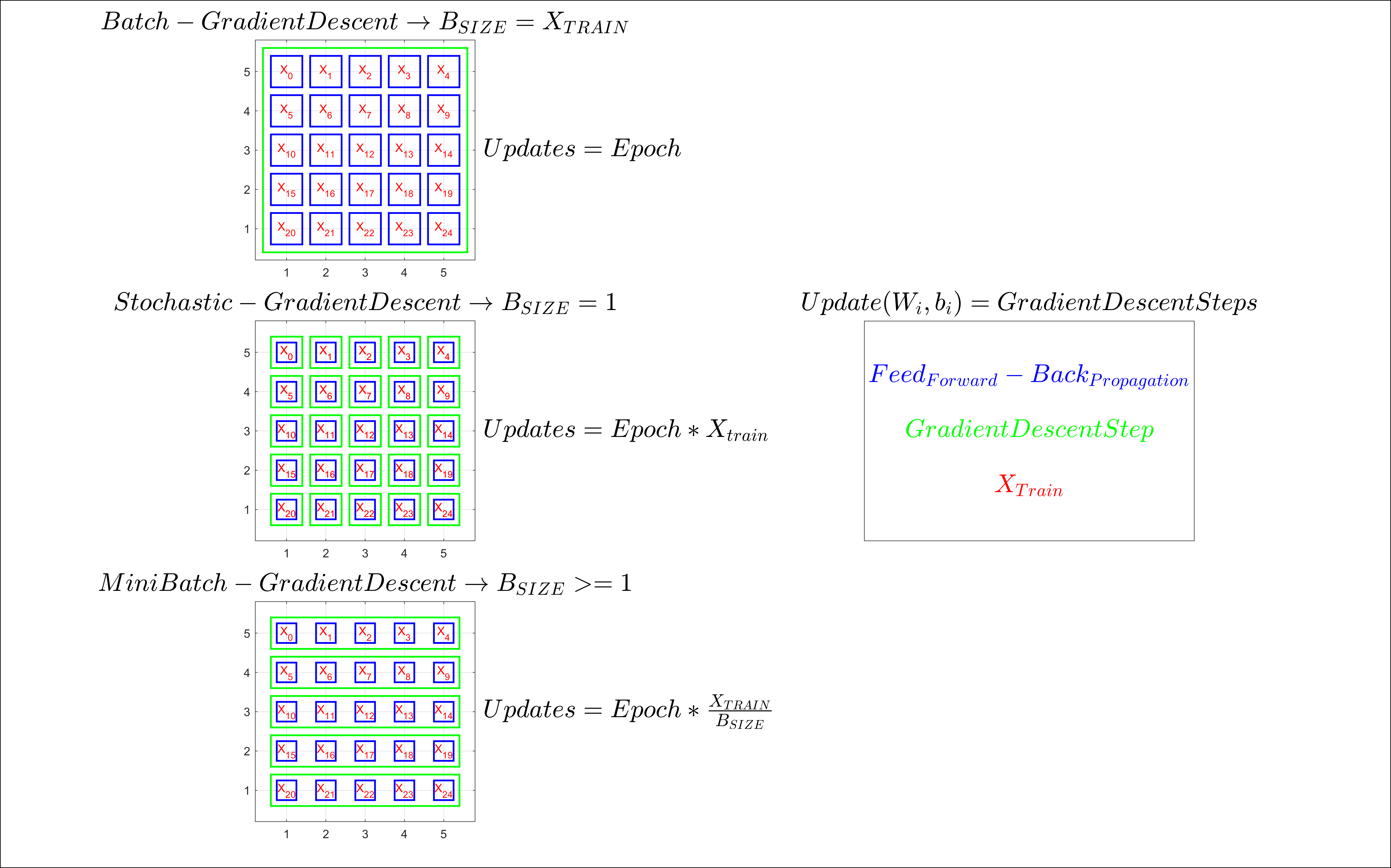

- Batch Gradient Descent.

- Stochastic Gradient Descent.

- Mini-Bach Gradient Descent.

# MINI BACH GRADIENT DESCENT

for epoch in n_epochs:

for batch in n_batches:

for all instances in the batch

#compute the derivative of the cost function

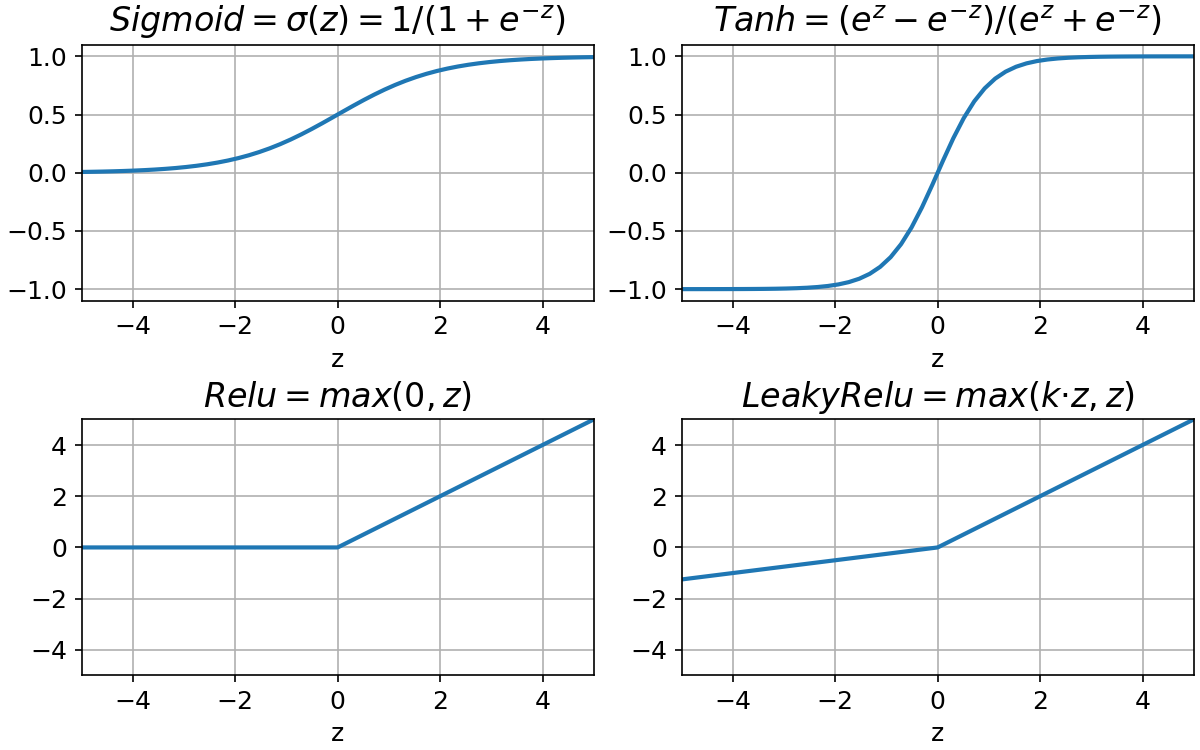

#update the weights and biasesTanh improves sigmoid function because with sigmoid all the weights of the same neuron must increase or decrease together as the activations will always be positive and the sign will depend on the error associated with the neuron. With Tanh the activations in the hidden layers would be equally balanced between positive and negative values.

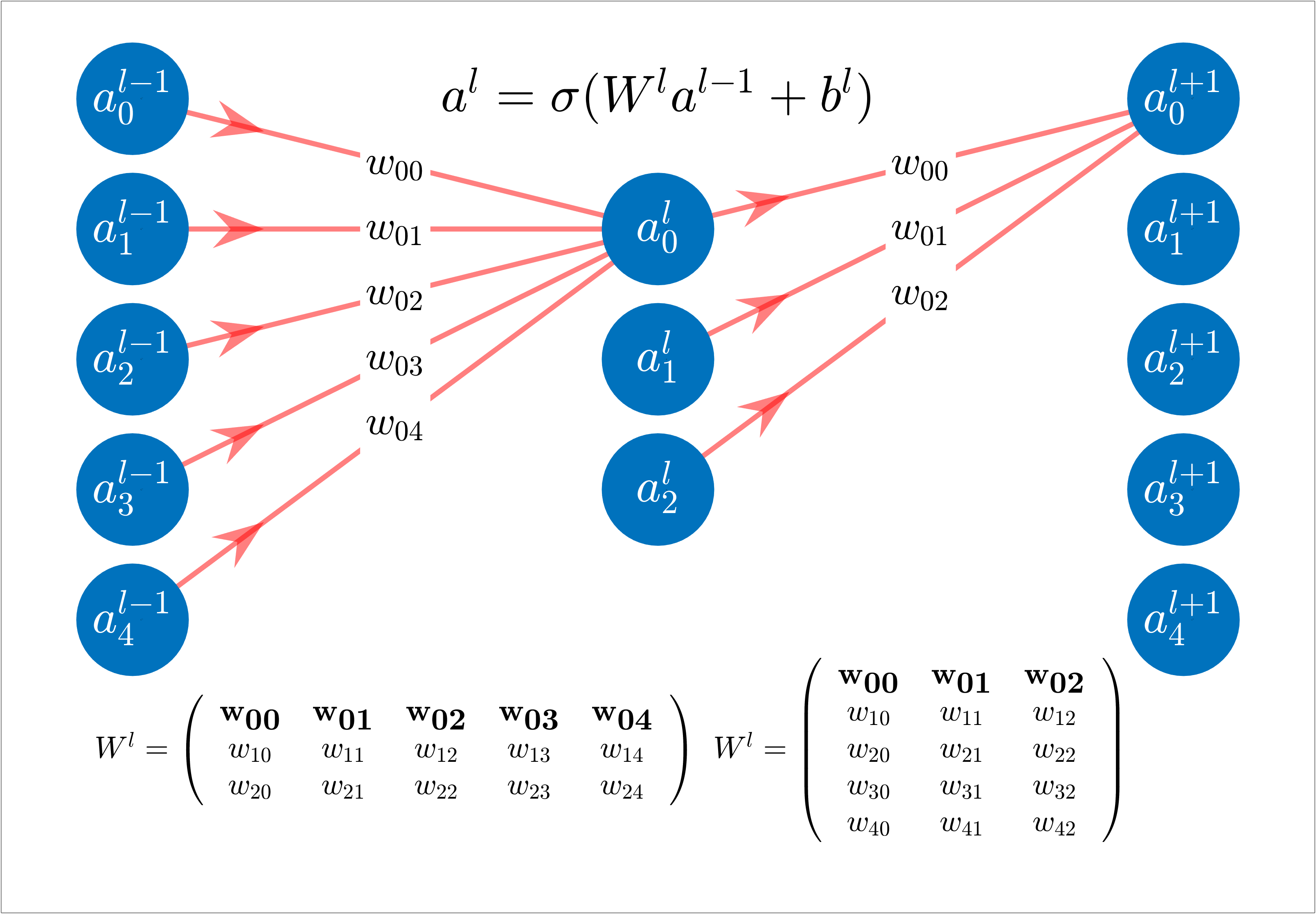

In vectorized form:

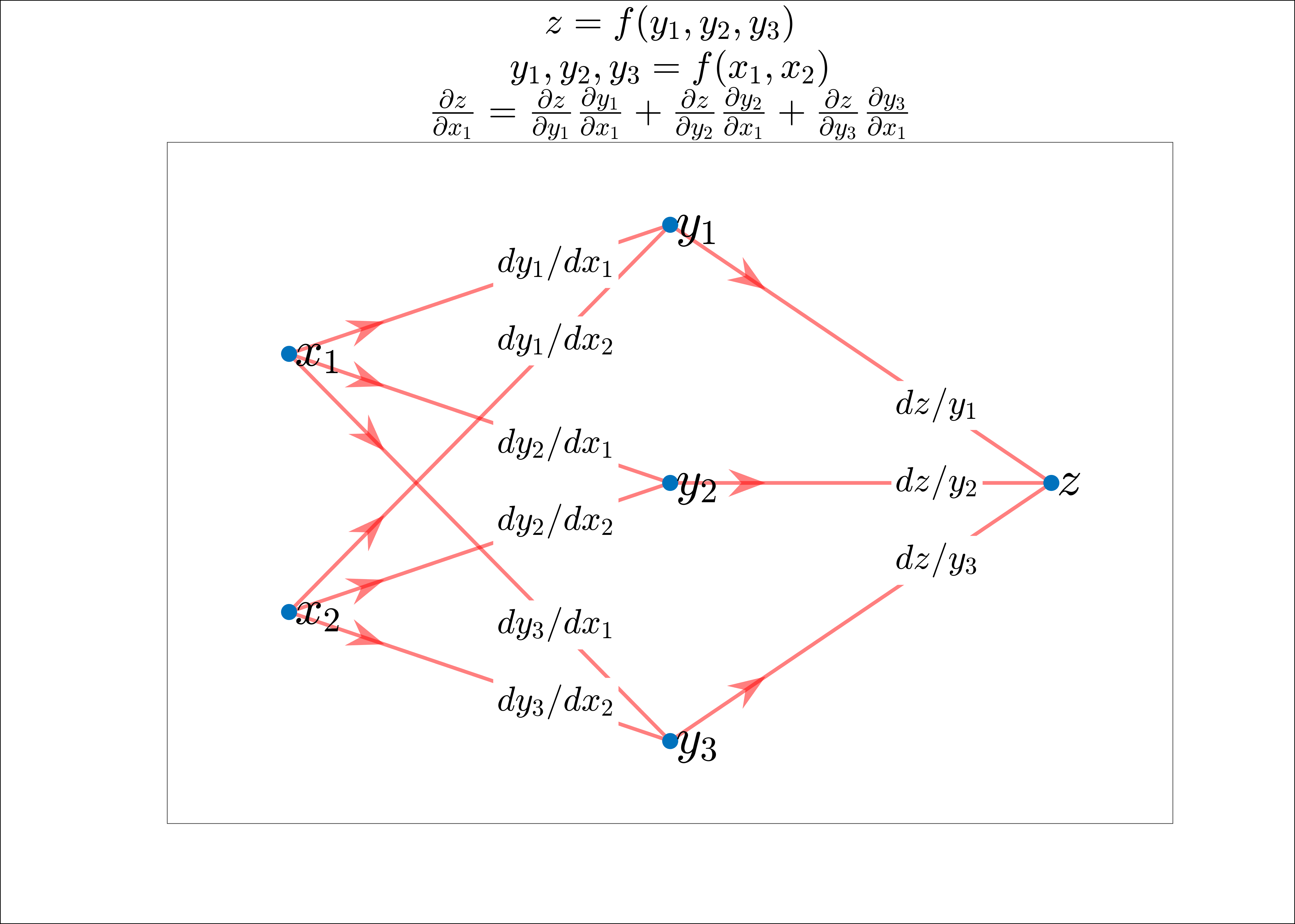

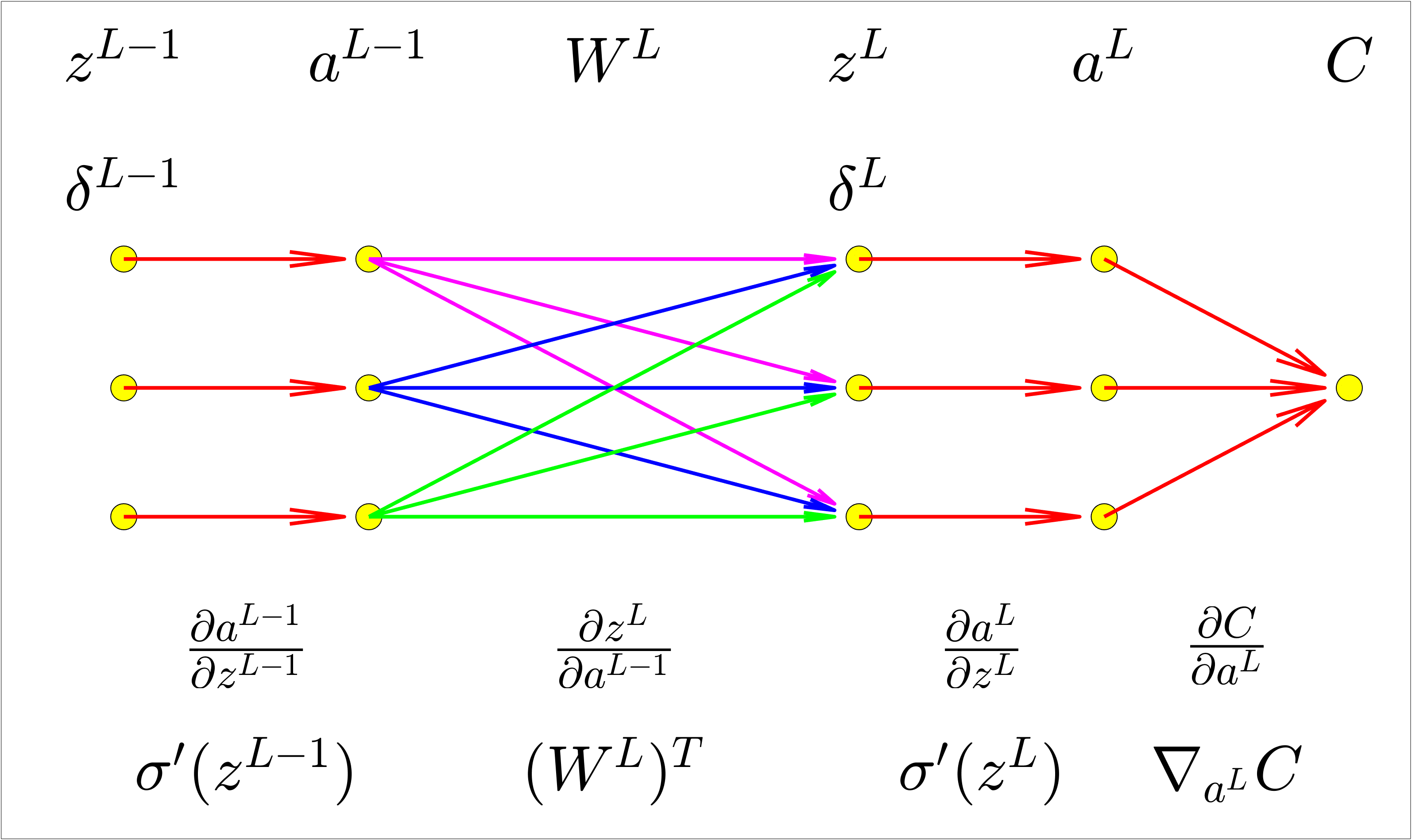

Backpropagation compute:

-

The partial derivatives

$\partial C_x/ \partial W^l$ and$\partial C_x/ \partial b^l$ for a single training input. We then recover$\partial C/ \partial W^l$ and$\partial C/ \partial b^l$ averaging training examples on the mini bach. -

$Error$ $\delta^l$ and then will relate$\delta^l$ to$\partial C/ \partial W^l$ and$\partial C/ \partial b^l$ . -

Weight and Biases will learn slowly if:

- The input neuron is low-activation

$\rightarrow a^{l-1}_k$ . - The output neuron has saturated

$\rightarrow \sigma'(z^l)$

- The input neuron is low-activation

-

Backpropagation Equations:

- Gradient Descent Combined with Backpropagation

- Chain rule applied in Backpropagation

-

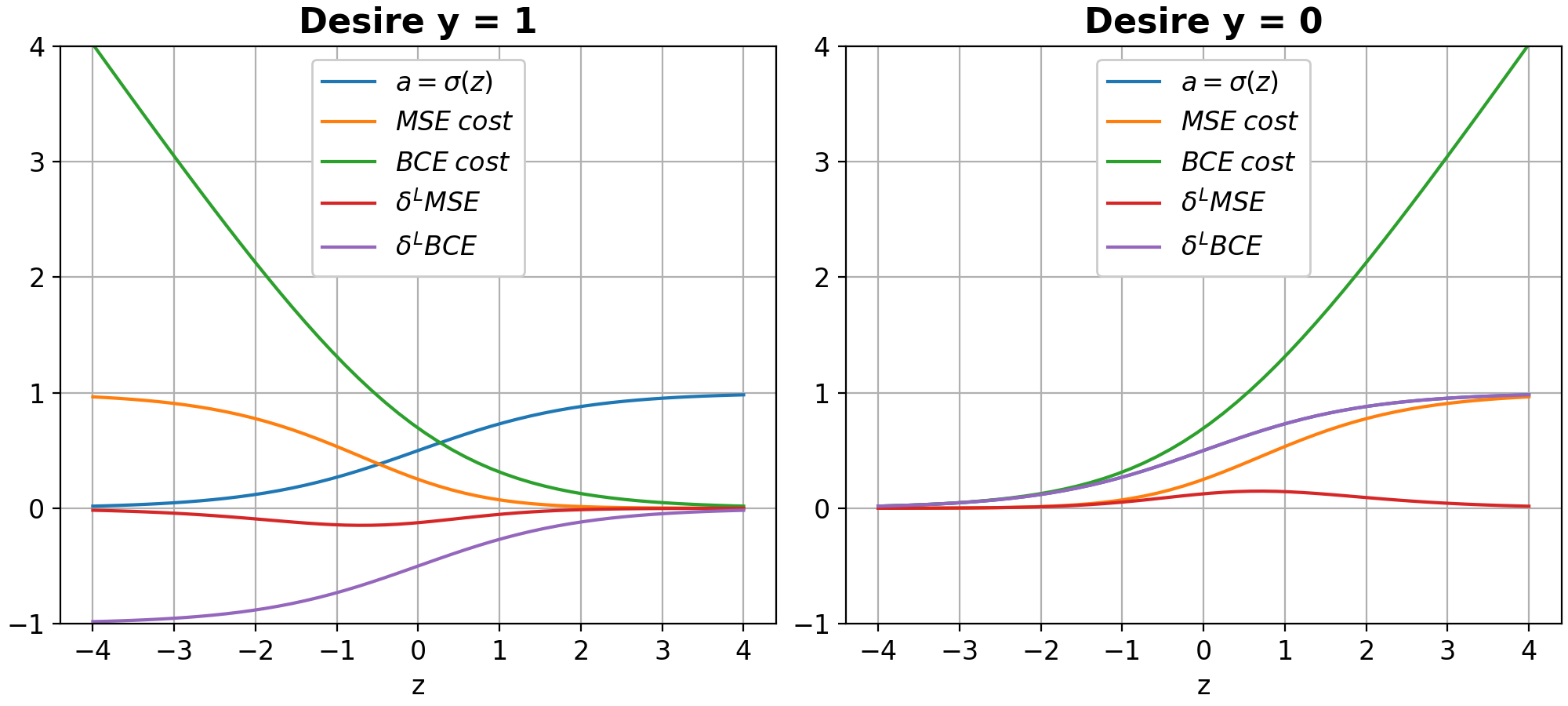

Quadratic Cost

$MSE$ : Often used in regression problems where the goal is to predict continuous values. -

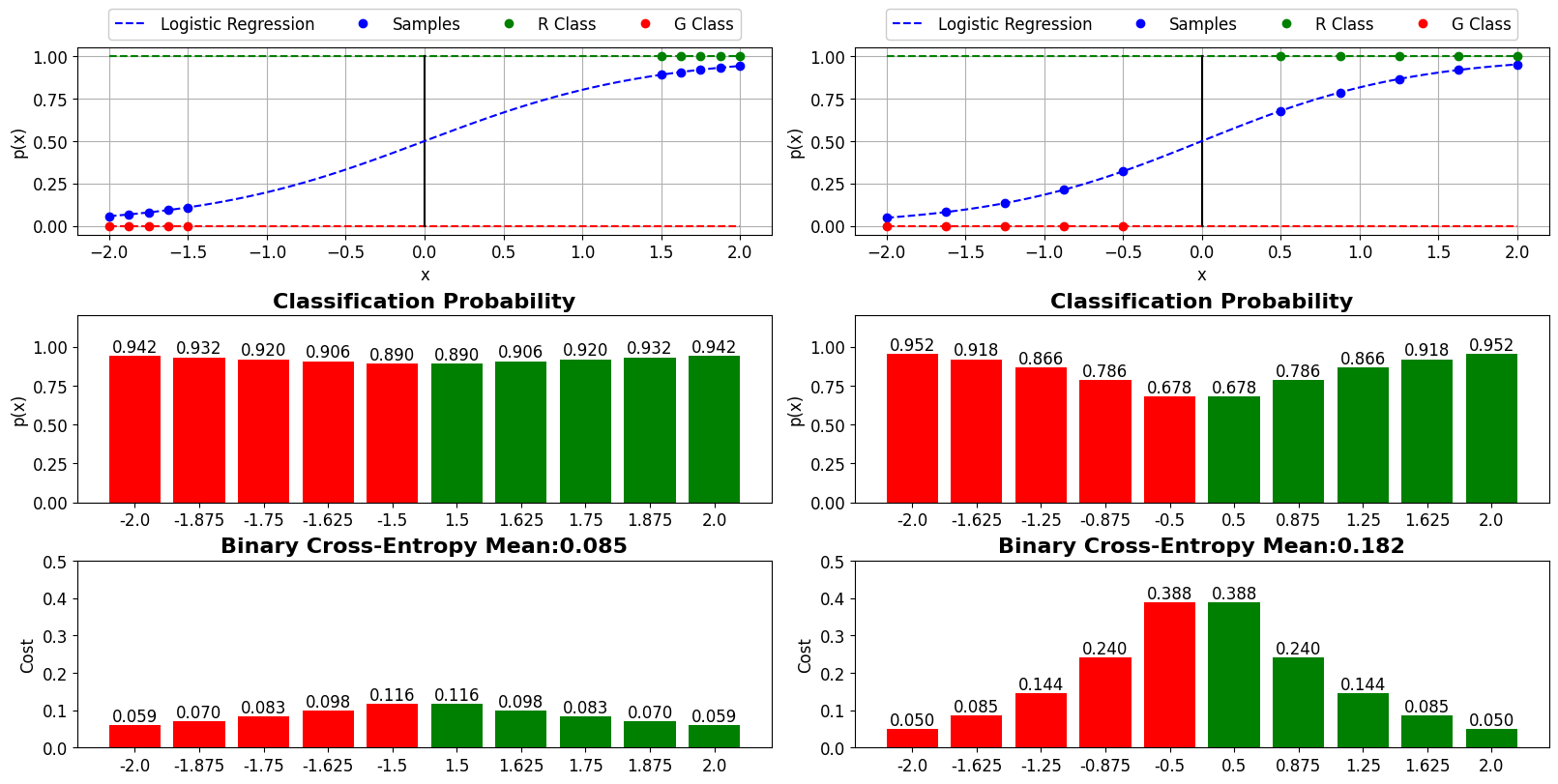

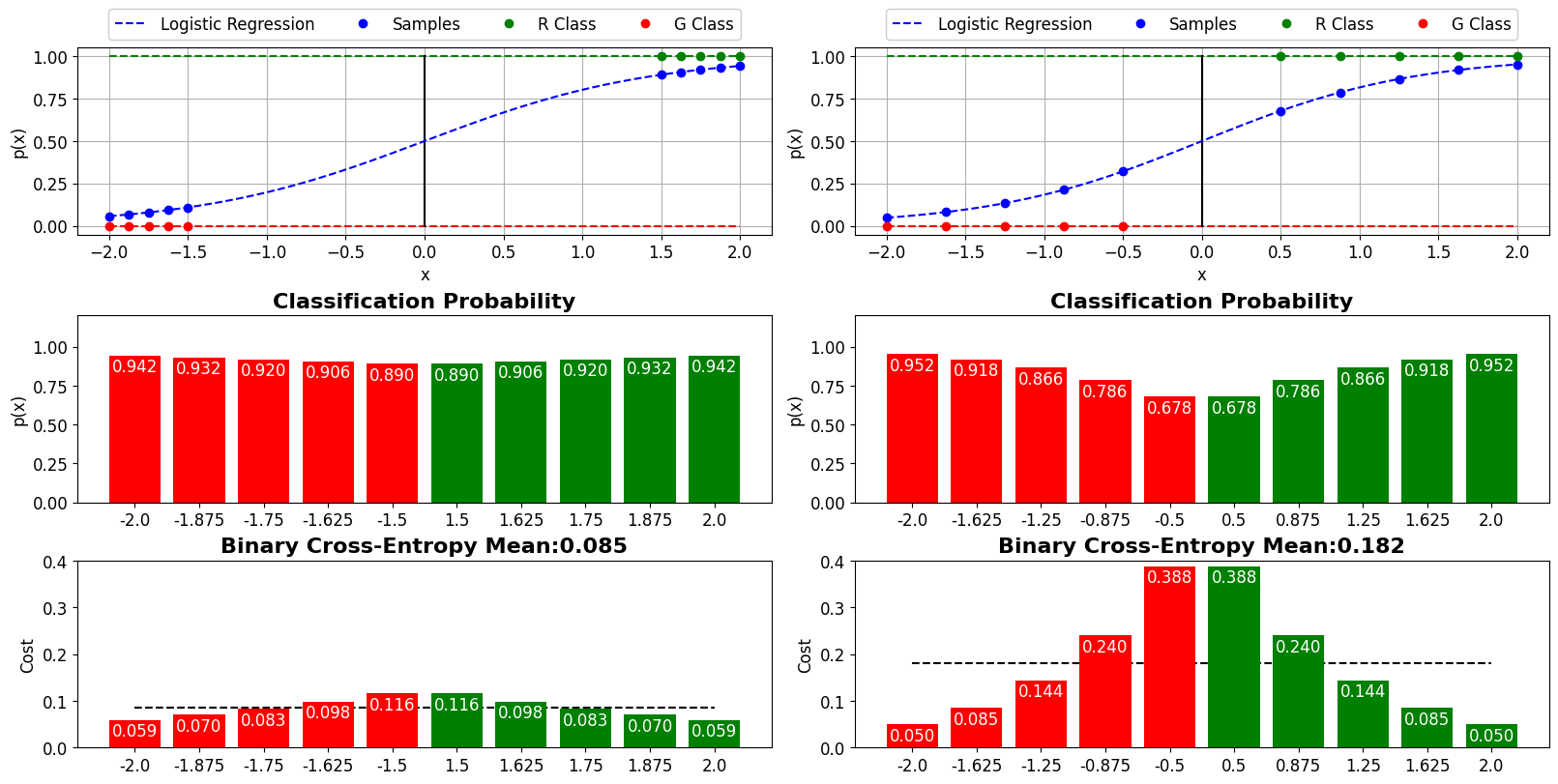

Binary Cross-Entropy

$BCE$ : Often used in classification problems where the goal is to predict discrete class labels

- Derivatives :

When the weights are updated using the CE cost function it does not matter if the neurons are saturated

-

Entropy:

$H(p)$ -

Cross Entropy:

$H(p,q)$

The activation function of the last layer can be thought of as a probability distribution. It can be useful with classification problems involving disjoint classes.

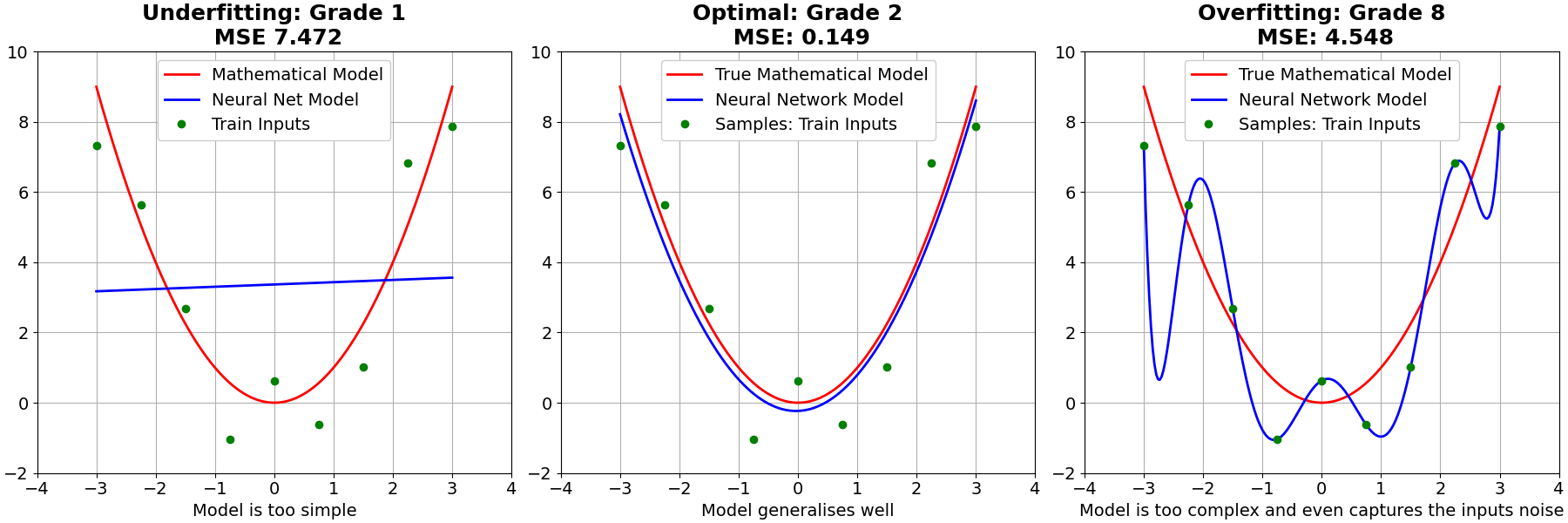

The effectis to make it so the network prefers to learn small weights. Large weights will only be allowed if they considerably improve the first part of the cost function. Regularization can be viewed as a way of compromising between finding small weights and minimizing the original cost function. The relative importance of the two elements of the compromise depends on the value of

Regularized networks are constrained to build relatively simple models based on patterns seen often in the training data, and are resistant to learning peculiarities of the noise in the training data.Thus, regularised neural networks tend to generalise better than non-regularised ones.

The dynamics of gradient descent learning in multilayer nets has a ``self-regularization effect´´.

When a particular weight has a large magnitude

The dropout procedure is like averaging the effects of a very large number of different networks. The different networks will overfit in different ways, and so, hopefully, the net effect of dropout will be to reduce overfitting.

If we think of our network as a model which is making predictions, then we can think of dropout as a way of making sure that the model is robust to the loss of any individual piece of evidence. In this, it's somewhat similar to L1 and L2 regularization, which tend to reduce weights, and thus make the network more robust to losing any individual connection in the network

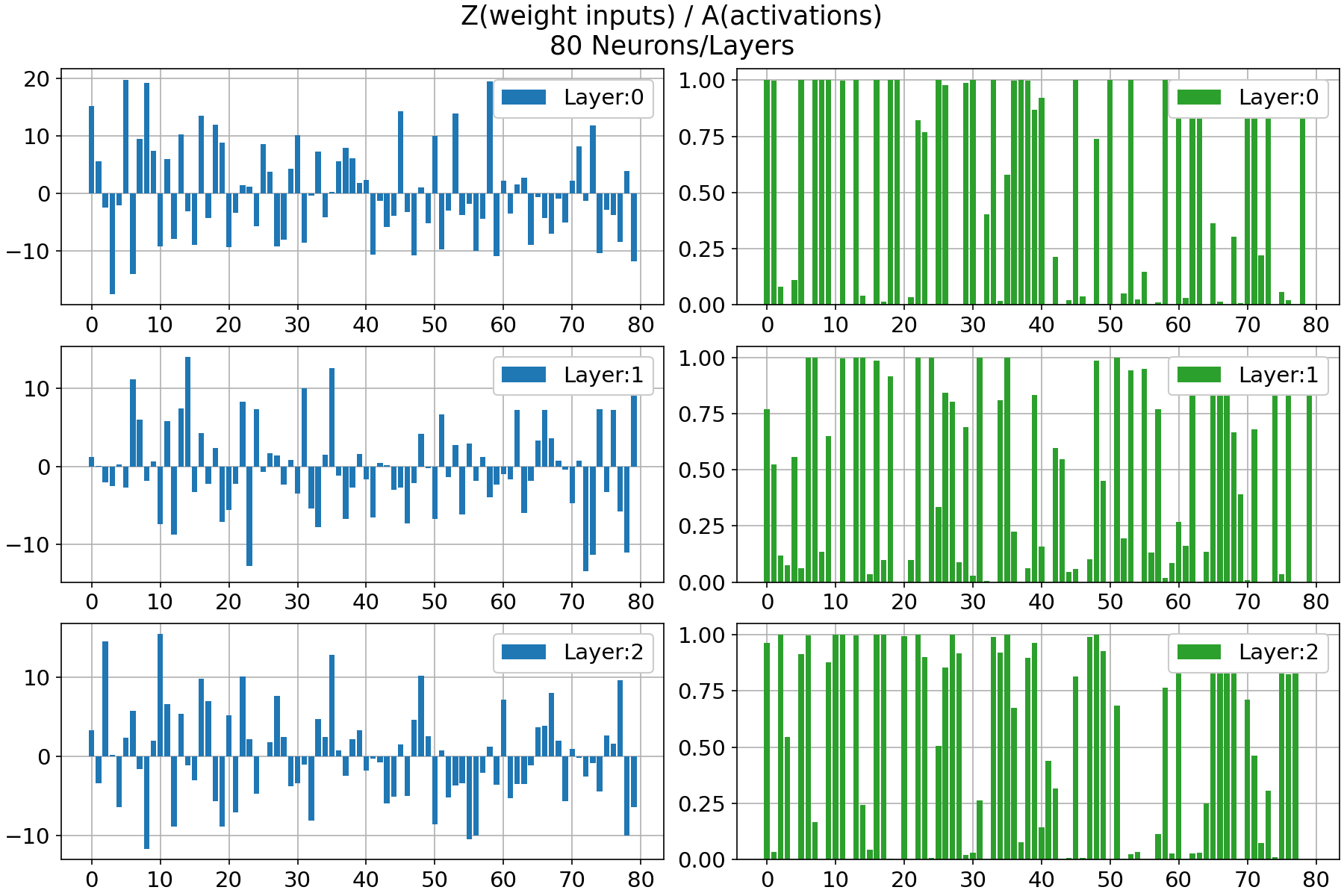

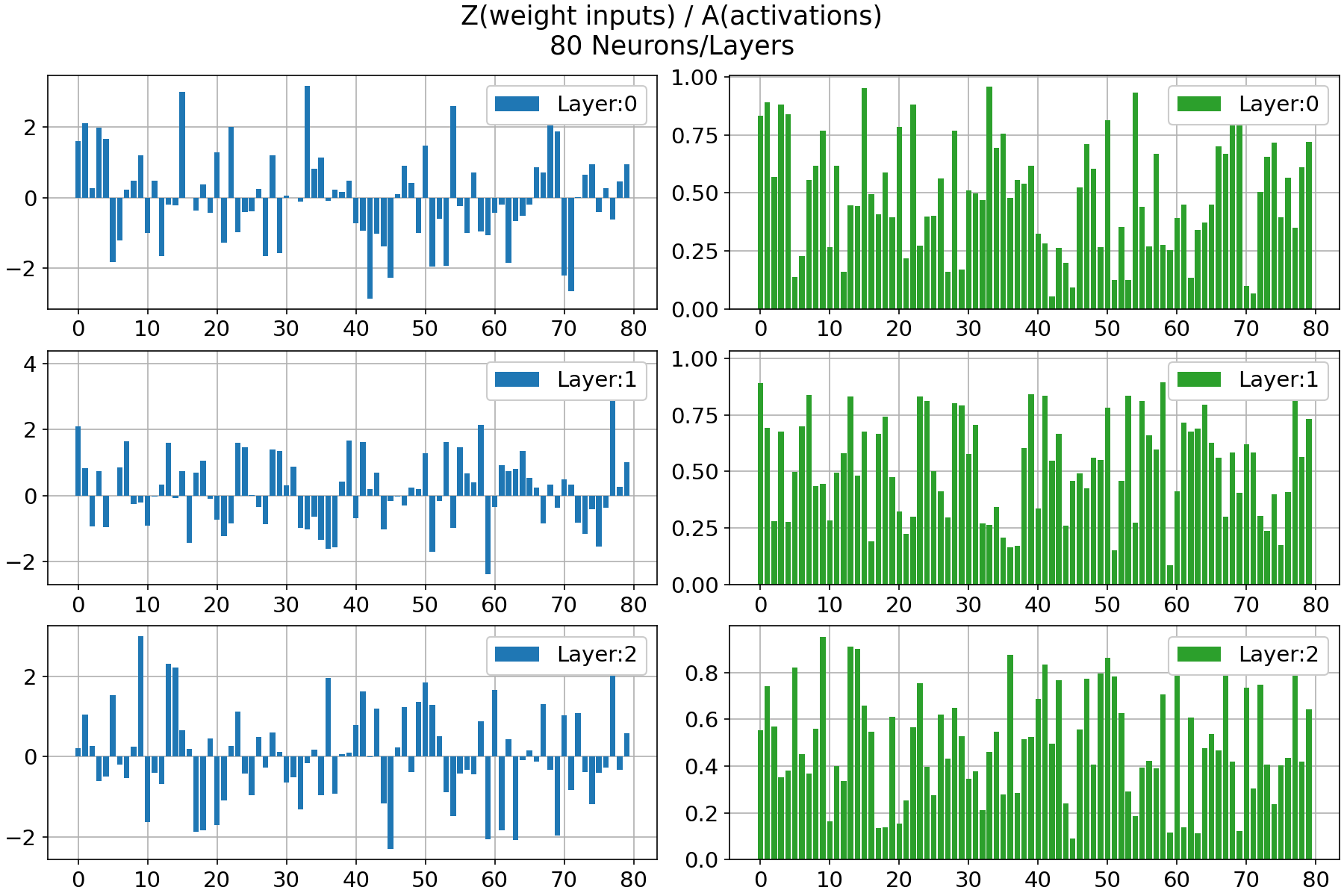

When the weights have a large magnitude, the sigmoid and tanh activation functions take on values very close to saturation. When the activations become saturated, the gradients move close to zero during backpropagation.

-

The problem of saturation of the output neurons causes a learning slowdown using the MSE cost function. This problem is solved using the BCE cost function.

-

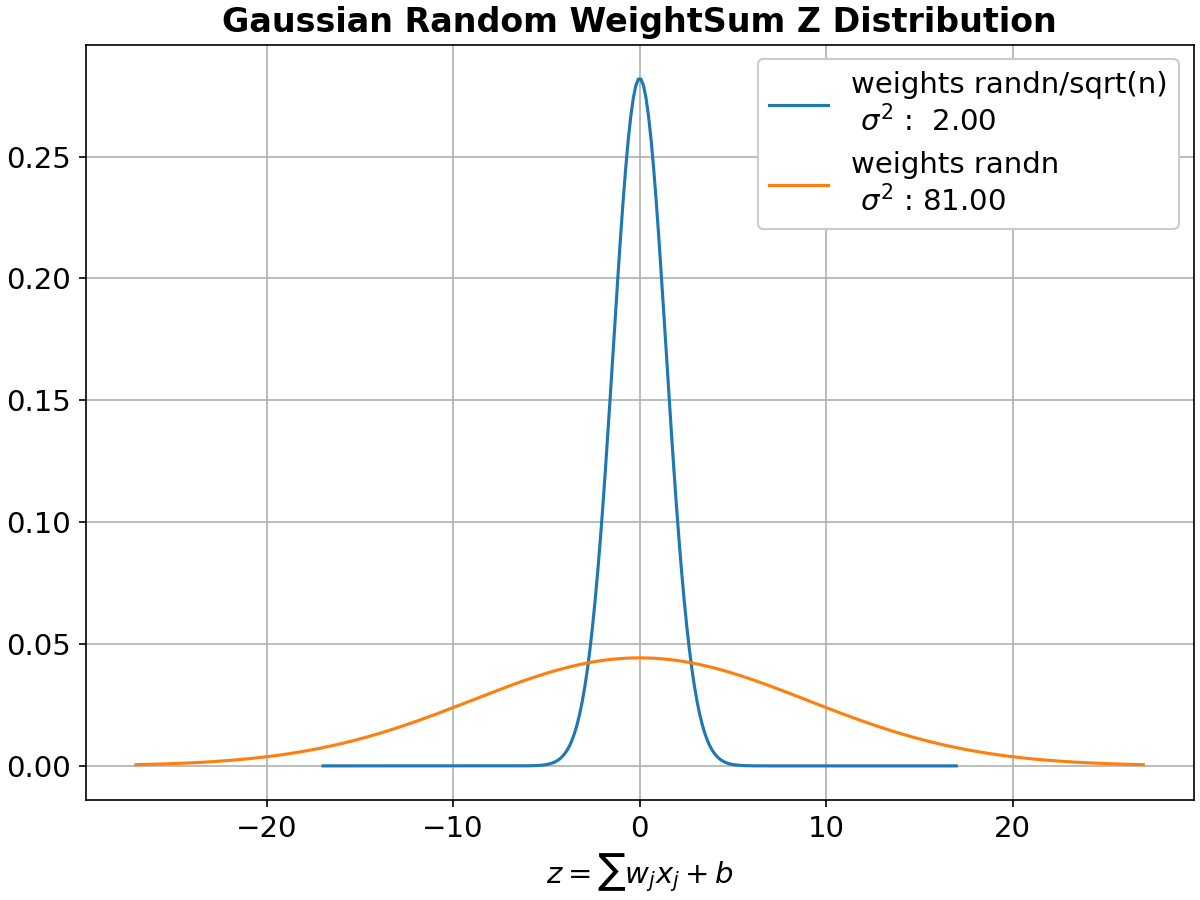

For the saturation of the hidden neurons this problem is solved with a correct weight initialization.

The idea is to initialize

-

Standard Normal Distribution: The weights for each connection between input neurons and hidden neurons are drawn independently from a standard normal distribution

$N(0,1)$ The mean of this distribution is 0, and the variance is 1. -

Variance in Hidden Neurons: The variance in the hidden neurons is influenced by the weights connecting the input neurons to the hidden neurons. Since each weight is drawn independently from a standard normal distribution, the overall variance in the hidden neurons would be proportional to the number of input neurons.

-

Effect on Learning: While random initialization is crucial for breaking symmetry and promoting effective learning, initializing weights without scaling can lead to challenges such as vanishing or exploding gradients, especially in deep networks.

# randn

weights = [np.random.randn(r,c) for r,c in zip(rows,cols)]

# normalized

weights = [np.random.randn(r,c)/np.sqrt(c) for r,c in zip(rows,cols)]- Reduce the number of classes and the test data

- Decreasing training cost

$\eta$ : 0.1, 1.0, 2.5, 5 - Validation accuracy:

$\lambda$ ,$m$ ,$Nº$ $HiddenNeurons$ - Early stopping to determine the number of training epochs: (Compute the classification accuracy on the validation data at the end of each epoch). Terminate training if the best classification accuracy doesn't improve for quite some nº of epochs

# training_data = [(x1,y1),(x2,y2)...(xn,yn)]

# len = 50000

# xi = array(784,1)

# yi = array(10,1)

# test_data = [(x1,y1),(x2,y2)...(xn,yn)]

# len = 10000

# xi = array(784,1)

# yi = number 0,1,2...9

# validation_data = [(x1,y1),(x2,y2)...(xn,yn)]

# len = 10000

# xi = array(784,1)

# yi = number 0,1,2...9n = 100

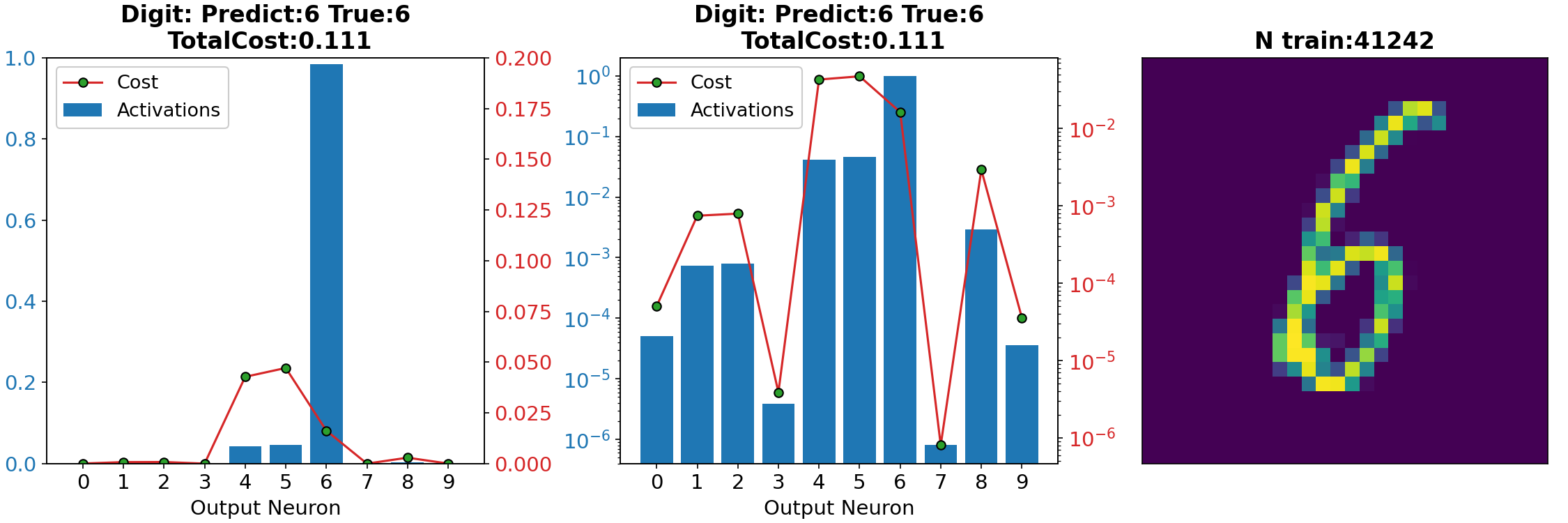

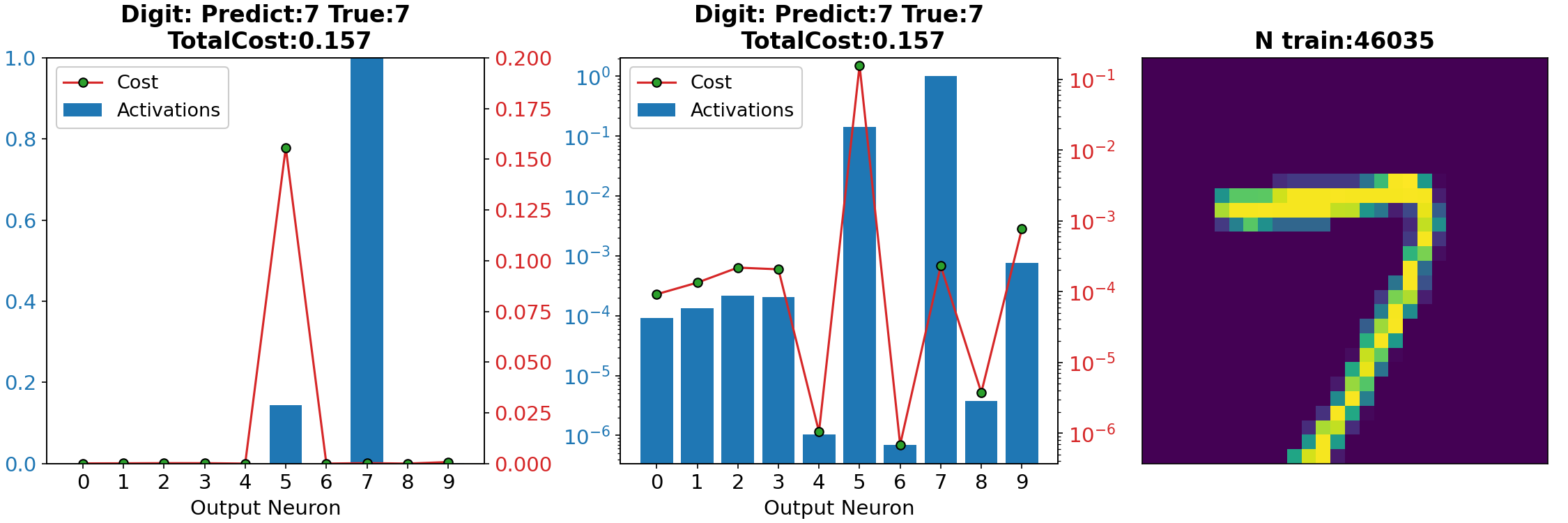

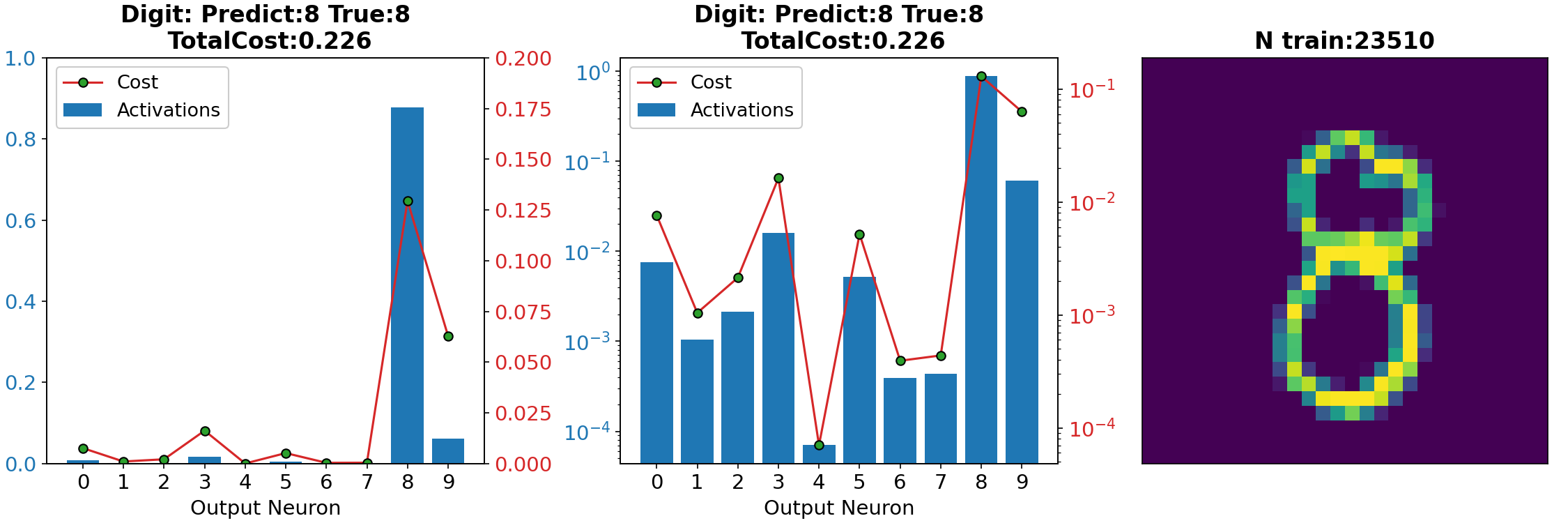

x, y = training_data[n]

a = net.feedforward(x)

# a: Net output

# array([[2.26639888e-03],

# [3.91142856e-04],

# [4.30652386e-05],

# [2.98756664e-06],

# [3.88572904e-04],

# [9.06726417e-01], Digit 5

# [1.95308412e-02],

# [6.02094721e-06],

# [8.41020120e-02],

# [3.07447887e-02]])

# y: Desire output

# array([[0.],

# [0.],

# [0.],

# [0.],

# [0.],

# [1.], Digit 5

# [0.],

# [0.],

# [0.],

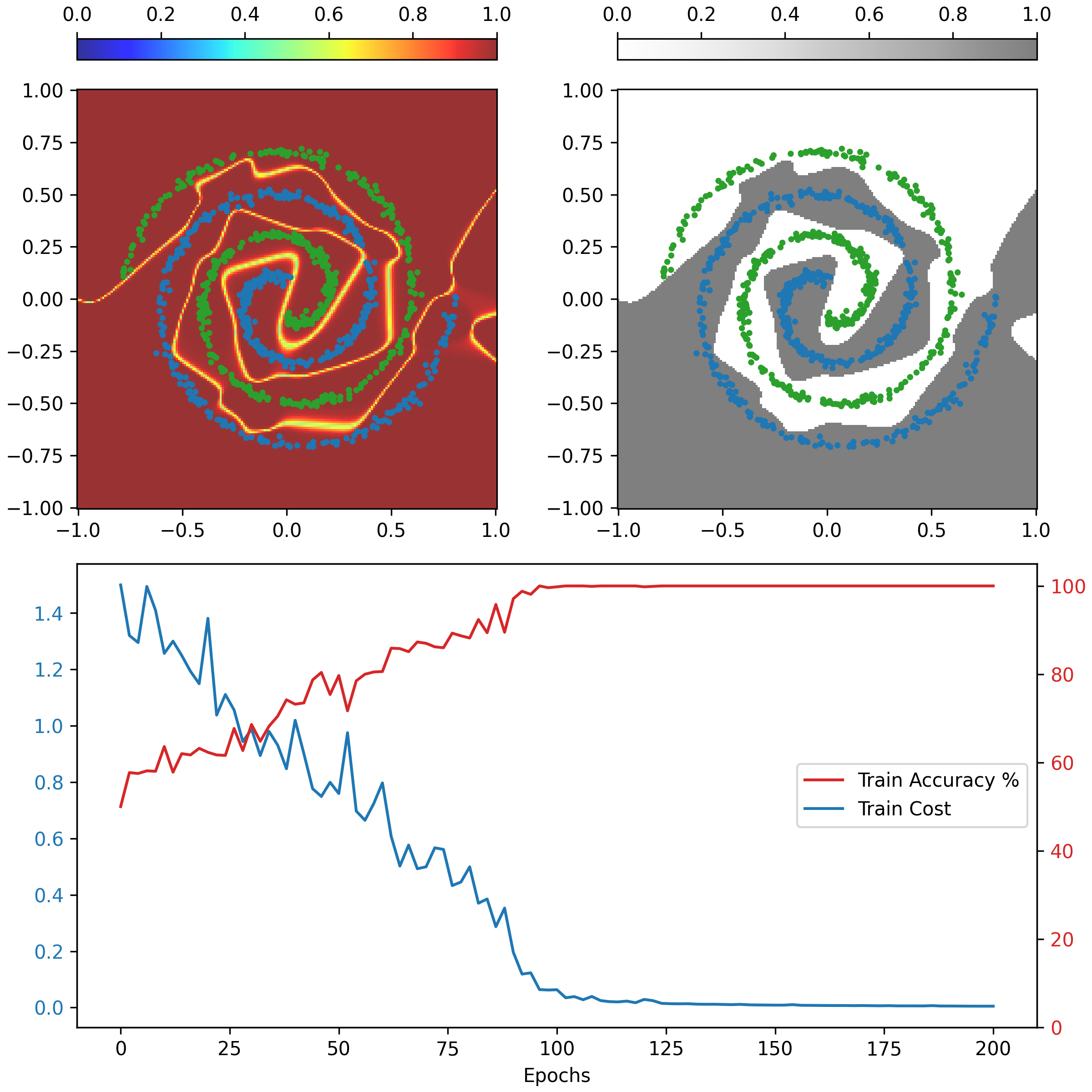

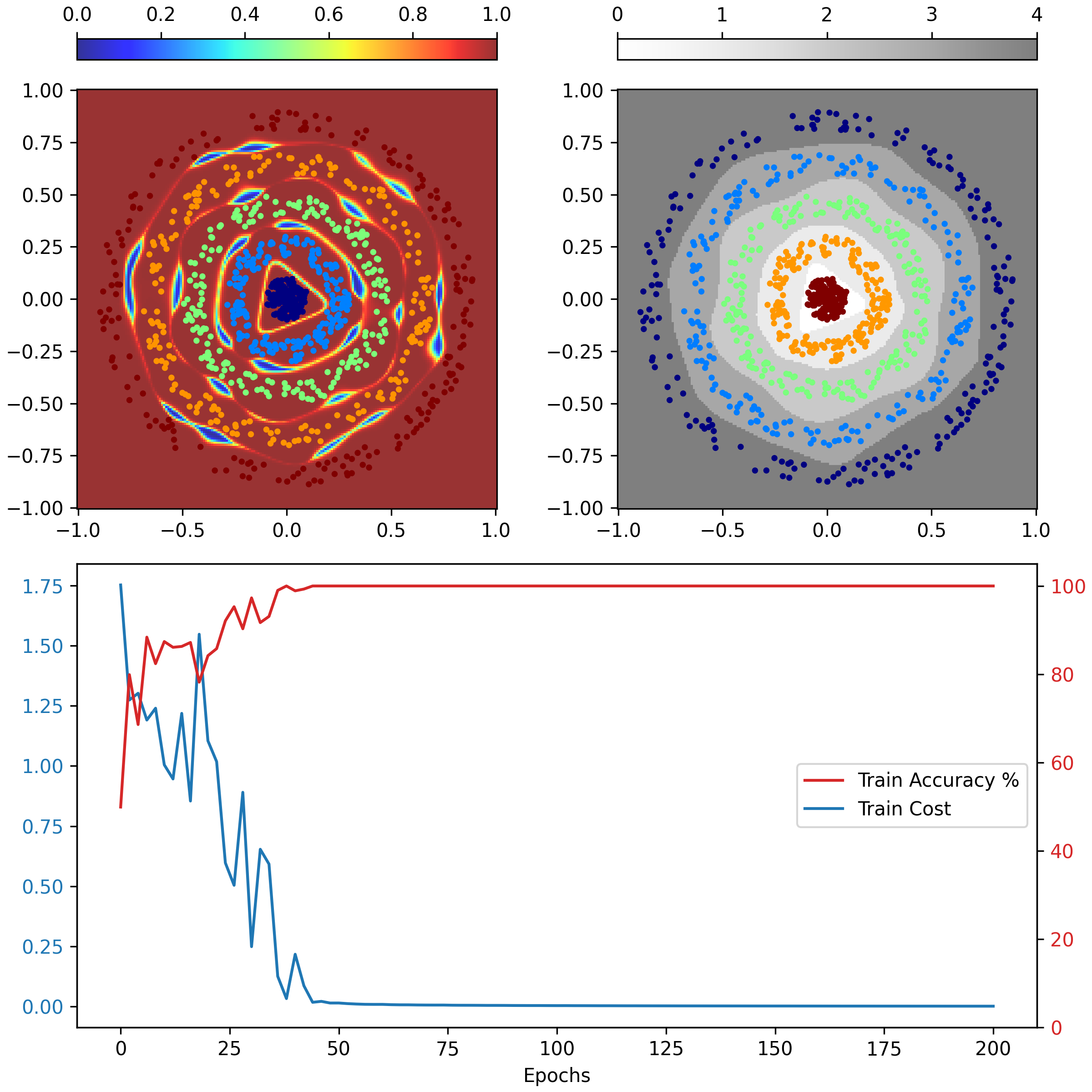

# [0.]])These animations show the ability of a Neural Network to transform the space in a non-linear way to create regions that allow to delimit and classify the input data. The colour gradient represents the normalised output of the network (first row) and the discrete colours represent the different classification regions (second row).

The first animation represents the evaluation of the network during the training process. The second one represents the evaluation after being trained, keeping the same architecture, hyperparameters, training data but different initialisations of weights.

Deriving the Backpropagation Equations from Scratch (Part 1)

Deriving the Backpropagation Equations from Scratch (Part 2)

Neural Networks and Deep Learning