The Advanced Reactor Modeling Interface (ARMI®) is an open-source tool that streamlines your nuclear reactor design/analysis needs by providing a software reactor at your fingertips and a rich ecosystem of utilities working in concert. It is made for and by professional reactor analysis teams and is maintained by TerraPower LLC, a nuclear technology development company.

ARMI:

- Provides a hub-and-spoke mechanism to standardize communication and coupling between physics kernels and the specialist analysts who use them,

- Facilitates the creation and execution of detailed models and complex analysis methodologies,

- Provides an ecosystem within which to rapidly and collaboratively build new analysis and physics simulation capabilities, and

- Provides useful utilities to assist in reactor development.

A few demos of ARMI can be seen in the ARMI example gallery.

Using ARMI plus a collection of ARMI-aware physics plugins, an engineering team can perform a full analysis of a reactor system and then repeat the same level of analysis with some changed input parameters for almost no additional cost. Even better, thousands of perturbed cases can be executed in parallel on large computers, helping conceptual design teams home in on an optimal design, or helping detailed design teams understand sensitivities all the way from, for example, an impurity in a control material to the peak structural temperature in a design-basis transient.

Note

ARMI does not come with a full selection of physics kernels. They will need to be acquired or developed for your specific project in order to make full use of this tool. Many of the example use-cases discussed in this manual require functionality that is not included in the open-source ARMI Framework.

In general, ARMI aims to enhance the quality, ease, and rigor of computational nuclear reactor design and analysis. Additional high-level overview about this system can be found in1.

Quick links| Source code | https://github.com/terrapower/armi |

| Documentation | https://terrapower.github.io/armi |

| Bug tracker | https://github.com/terrapower/armi/issues |

| Plugin directory | https://github.com/terrapower/armi-plugin-directory |

| Contact | armi-devs@terrapower.com |

Before starting, you need to have Python 3.7+ on Windows or Linux.

Get the ARMI code, install the prerequisites, and fire up the launcher with the following commands. You probably want to do this in a virtual environment as described in the Installation documentation. Otherwise, the dependencies could conflict with your system dependencies.

$ git clone https://github.com/terrapower/armi

$ cd armi

$ pip3 install -r requirements.txt

$ python3 setup.py install

$ armiThe easiest way to run the tests is to install tox and then run:

$ pip3 install -r requirements-testing.txt

$ tox -- -n 6This runs the unit tests in parallel on 6 processes. Omit the -n 6 argument to run on a single process.

From here, we recommend going through a few of our gallery examples and tutorials to start touring the features and capabilities and then move on to the User Manual.

Nuclear reactor design requires, among other things, answers to the following questions:

- Where are the neutrons? How fast are they moving? In which direction?

- How quickly are atomic nuclei splitting? How long until the fuel runs out? How many atoms in the structure are being energetically displaced?

- How much heat do these reactions produce? How quickly must coolant flow past the fuel to maintain appropriate temperatures? What are the temperatures of the fuel, coolant, and structure?

- Can the structural arrangement support itself given the temperatures and pressures induced by the flowing coolant? For how long?

- If a pump loses power or a control rod accidentally withdraws, how quickly will the chain reaction stop while keeping radiation contained?

- How much used nuclear fuel is generated per useful energy produced? How long until it decays to stability?

- Where and when should we move the fuel to most economically maintain the chain reaction?

- What's the dose and activation above the head and in the secondary loop?

- How does containment handle various postulated accidents?

- How does the building handle earthquakes?

Digital computers have assisted in nuclear technology development since the days of the ENIAC in the 1940s. We now understand reactor physics well enough to build detailed simulations, which can answer many of these design questions in a cost-effective, and flexible manner. This allows us to simulate all kinds of different reactors with different fuels, coolants, moderators, power levels, safety systems, and power cycles. We can run our virtual reactors through the decades, tossing various off-normal conditions at them now and then, to see how they perform in terms of capability, economics, and safety.

Note

Of course, experimental validation remains necessary for many new configurations and situations during licensing.

Perhaps surprisingly, some nuclear software written in the 1960s is still in use today (mostly ported to Fortran 90 by now). These codes are validated against physical experiments that no longer exist. Meanwhile, new cutting-edge nuclear software is being developed today for powerful computers. Both old and new, these tools are often challenging to operate and to use in concert with other sub-specialty codes that are necessary to reach a full system analysis.

The ARMI approach was born out of this situation: how can we best leverage an eclectic mix of legacy and modern tools with a small team to do full-scope analysis? We built an environment that lets us automate the tedious, uncoupled, and error-prone parts of reactor engineering/analysis work. We can turn around a very meaningful and detailed core analysis given a major change (e.g. change power by 50%) in just a few weeks. We can dispatch hundreds of parameter sweeps to multiple machines and then perform multiobjective optimization on the resulting design space.

The ARMI system is largely written in the Python programming language. Its high-level nature allows nuclear and mechanical engineers to rapidly automate their analysis tasks from their sub-specialties. This helps eliminate the translation step between computer-scientists and power plant design engineers. This allows good division of labor: the computer scientists can focus on the overall performance and maintainability of the framework, while the power plant engineers focus on power plant engineering.

We've spent 10 years developing this system in a reactor design context. We focused primarily on what's needed to do advanced reactor design and analysis.

Because of ARMI's high-level nature, we believe we can collaborate effectively with all ongoing reactor software developments.

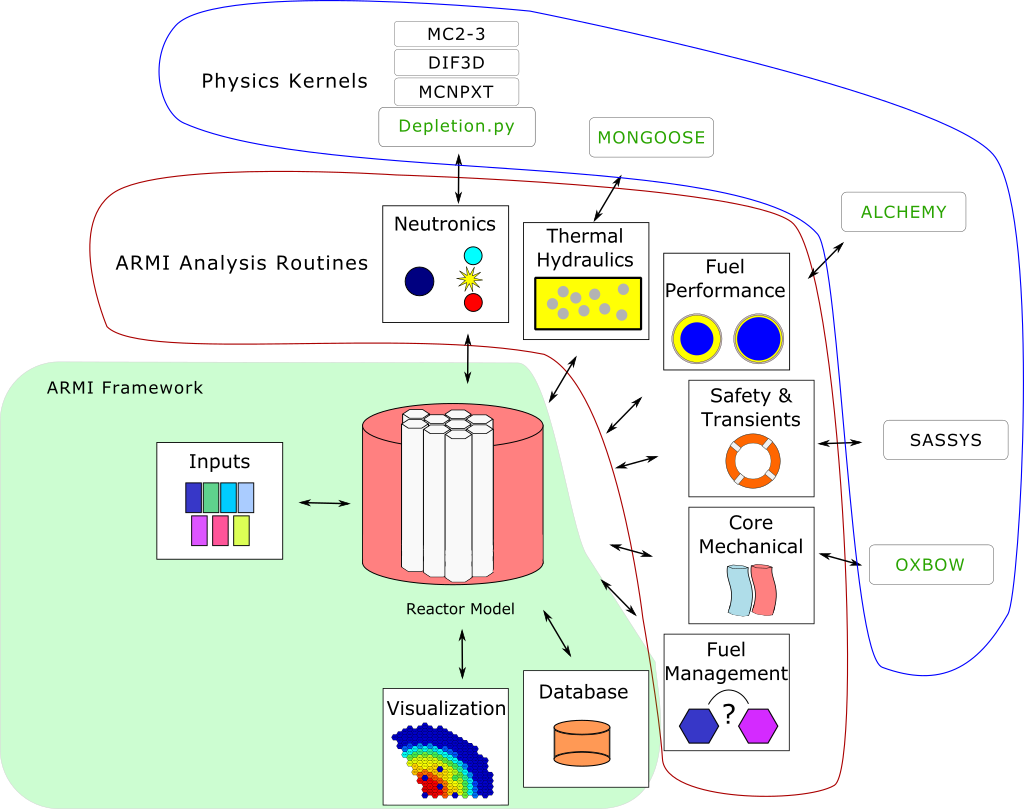

ARMI provides a central place for all physics kernels to interact: the Reactor Model. All modules read state information from this Reactor and write their output to it. This common interface allows seamless communication and coupling between different physics sub-specialties. If you plug one new physics kernel into ARMI, it becomes coupled to N other kernels. The ARMI Framework, depicted in green below, is the majority of the open source package. Several skeletal analysis routines are included as well to perform basic data management and to help align efforts on external physics kernels.

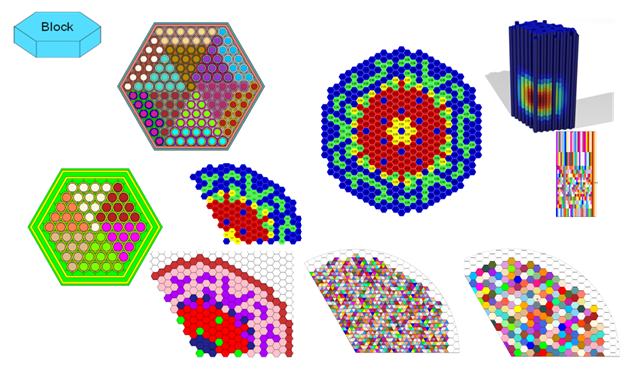

Figure 1. The schematic representation of the ARMI data model.ARMI can quickly and easily produce complex input files with high levels of detail in various approximations. This enables users to perform rapid high-fidelity analyses to make sure all important physics are captured. It also enables sensitivity studies of different modeling approximations (e.g. symmetries, transport vs. diffusion vs. Monte Carlo, subchannel vs. CFD, etc.).

Figure 2. A variety of approximations in hexagonal geometry (1/3-core, full core, pin detailed, etc.) are shown, all derived from one consistent input file. ARMI supports Cartesian, Hex, RZ, and RZTheta geometric grids and includes many geometric components. Additionally, users can provide custom geometric elements.The ARMI reactor model is fully accessible via a Python-based API, meaning that power-users and developers have full access to the details of the plant at all times. Developers adding new physics features can take advantage of the ARMI data management structure by simply reading and writing to the Reactor state. Leveraging the infrastructure of ARMI, progress can be made rapidly.

Power-user analysts can modify the plant in many ways. For instance, removing all sodium coolant is a one-liner:

core.setNumberDensity('NA23',0.0)and finding the peak power density is easy:

core.getMaxParam('pdens')Any ARMI state can be written out to whichever format the user desires, meaning that nominally identical cases can be produced for multiple similar codes in sensitivity studies. To read power densities, simply read them off the assembly objects. Instead of producing spreadsheets and making plots manually, analysts may write scripts to generate output reports that run automatically.

Writing a module within ARMI automatically features access to the ARMI API, including:

- Cross section processing

- Material properties

- Thermal expansion

- Database persistence

- Data visualization

- A code testing, documentation, and version control system

Given input describing a reactor, a typical ARMI run loops over a set of plugins in a certain sequence. Some plugins trigger third-party simulation codes, producing input files for them, executing them, and translating the output back onto the reactor model as state information. Other plugins perform physics simulations directly. A variety of plugins are available from TerraPower LLC with certain licensing terms, and it is our hope that a rich ecosystem of useful plugins will be developed and curated by the community (university research teams, national labs, other companies, etc.).

For example, one ARMI sequence may involve the calculation of:

- nuclear cross sections,

- global flux and power,

- subchannel temperatures,

- duct wall pressures,

- cladding strain and wastage,

- fission gas pressure,

- reactivity feedbacks (including from core mechanical),

- flow orificing,

- the equilibrium fuel cycle,

- control rod worth,

- shutdown margin,

- frequency stability margins,

- total levelized cost of electricity for the run,

- and the peak cladding temperature in a variety of design and beyond-design basis transients.

Another sequence may simply compute the cost of feed uranium and enrichment in an initial core and quit. The possibilities are limited only by our creativity.

These large runs may also be run through the multiobjective design optimization system, which runs many cases with input perturbations to help find the best overall system, considering all important physics at the same time.

Other interest may come from the following:

A nuclear reactor research scientist, whether at a national lab or on a graduate or undergraduate university team, may benefit greatly from using ARMI. It's not uncommon for such people to spend significant fractions of effort on data management. ARMI will handle the tedium so that researchers can better focus on designing and testing their research.

For example, if an ARMI input file describing the FFTF reactor in detail is provided, the researcher can start running benchmark cases with their new code method very rapidly, rather than spending the time building their own FFTF model.

If someone wants to try varying nuclear cross sections by a percent here and there to compute sensitivities, ARMI is a perfect platform upon which to operate.

If a reactor designer wants to try out a new Machine Learning algorithm for fuel management, plugging it into ARMI and having it run on all the physics kernels of the ARMI ecosystem will be a great way to prove its true value (note that this requires a rich ARMI physics ecosystem).

As various companies evaluate their ideas, they need tools for analysis. They can pick up ARMI and save 10 years of development and hit the ground running by plugging in their design-specific physics kernels and proprietary design inputs. ARMI's parameter sweep features, reactor model, and parallel utilities will all come in handy immediately.

People at well-established utilities or vendors can hook ARMI into their legacy systems and increase their overall productivity.

If an enthusiast wants to try out a reactor idea they have, they can use ARMI (plus some physics kernels) to quickly get some performance metrics. They can see if their idea has wings, and if it does, they can then find a way to bring it to engineering and commercial reality.

ARMI was originally created by TerraPower, LLC near Seattle WA starting in 2009. Its founding mission was to determine the optimal fuel management operations required to transition a fresh Traveling Wave Reactor core from startup into an equilibrium state. It started out automating the Argonne National Lab (ANL) fast reactor neutronics codes, MC2 and REBUS. The reactor model design was made with the intention of adding other physics capabilities later. Soon, simple thermal hydraulics were added and it's grown ever since. It has continuously evolved towards a general reactor analysis framework.

Following requests by outside parties to use ARMI, we started working on a more modular architecture for ARMI, allowing some of the intertwined physics capabilities to be separated out as plugins from the standalone framework.

The nuclear industry is small, and it faces many challenges. It also has a tradition of secrecy. As a result, there is risk of overlapping work being done by other entities.

We hypothesize that collaborating on software systems can help align some efforts worldwide, increasing quality and efficiency. In reactor development, the idea is generally cheap. It's the shakedown, technology and supply chain development, engineering demo, and commercial demo that are the hard parts.

Thus, ARMI was released under an open-source license in 2019 to facilitate mutually beneficial collaboration across the nuclear industry, where many teams are independently developing similar reactor analysis/automation frameworks. TerraPower will make its proprietary analysis routines, physics kernels, and material properties available under commercial licenses.

We also hope that if more people can rapidly analyze the performance of their reactor ideas, limited available funding can be spent more effectively.

Being largely written in the Python programming language, the ARMI system works on basically any kind of computer. We have developed it predominantly within a Microsoft Windows environment, but have performed tests under various flavors of Linux as well. It can perform meaningful analysis on a single laptop, but the full value of design optimization and large problems is realized with parallel runs over MPI with 32-128 CPUs, or more (requires installation optional mpi4py library). Serious engineering models can consume significant RAM, so at least 16 GB is recommended.

The original developer's HPC environment has been Windows based, so some development is needed to support the more traditional Linux HPC environments.

You can get help with ARMI by either making issues on our github page or by e-mailing armi-devs@terrapower.com.

Due to TerraPower goals and priorities, many ARMI modules were developed with the sodium-cooled TWR as the target, and are not necessarily yet optimized for other plants. On the other hand, we have attempted to keep the framework general where possible, and many modules are broadly applicable to many reactors. We have run parts of ARMI on various SFRs (TWRs, FFTF, Joyo, Phenix), some fast critical assemblies (such as ZPPRs and BFS), molten salt reactors, and some thermal systems. Support for the basic needs of thermal reactors (like a good spatial description of pin maps) exists but has not been subject to as much use.

ARMI was developed within a rapidly changing R&D environment. It evolved accordingly, and naturally carries some legacy. We continuously attempt to identify and update problematic parts of the code. Users should understand that ARMI is not a polished consumer software product, but rather a powerful and flexible engineering tool. It has the potential to accelerate work on many kinds of reactors. But in many cases, it will require serious and targeted investment.

ARMI was largely written by nuclear and mechanical engineers. We (as a whole) only really, truly, recognized the value of things like static typing in a complex system like ARMI somewhat recently. Contributions from software engineers are more than welcome!

ARMI has been written to support specific engineering/design tasks. As such, polish in the GUIs and output is somewhat lacking.

Most of our code is in the camelCase style, which is not the normal style for Python. This started in 2009 and we have stuck with the convention.

TerraPower and ARMI are registered trademarks of TerraPower, LLC. Other trademarks and registered trademarks used in this Manual are the property of the respective trademark holders.

The ARMI system is licensed as follows:

Copyright 2009-2022 TerraPower, LLC

Licensed under the Apache License, Version 2.0 (the "License");

you may not use this file except in compliance with the License.

You may obtain a copy of the License at

http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0

Unless required by applicable law or agreed to in writing, software

distributed under the License is distributed on an "AS IS" BASIS,

WITHOUT WARRANTIES OR CONDITIONS OF ANY KIND, either express or implied.

See the License for the specific language governing permissions and

limitations under the License.Be careful when including any dependency in ARMI (say in a requirements.txt file) not to include anything with a license that superceeds our Apache license. For instance, any third-party Python library included in ARMI with a GPL license will make the whole project fall under the GPL license. But a lot of potential users of ARMI will want to keep some of their work private, so we can't allow any GPL tools.

For that reason, it is generally considered best-practice in the ARMI ecosystem to only use third-party Python libraries that have MIT or BSD licenses.

Touran, Nicholas W., et al. "Computational tools for the integrated design of advanced nuclear reactors." Engineering 3.4 (2017): 518-526. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENG.2017.04.016↩