In order to use this command is that easy as positioning into the directory you like to initialize the repo:

...Desktop$ mkdir new_repository_directory

...Desktop$ cd new_repository_directory

...Desktop/new_repository_directory$ git init

then you will have your git repository locally in your own machine

Here's a brief synopsis on each of the items in the .git directory:

- config file - where all project specific configuration settings are stored. From the Git Book:

Git looks for configuration values in the configuration file in the Git directory (.git/config) of whatever repository you’re currently using. These values are specific to that single repository.

For example, let's say you set that the global configuration for Git uses your personal email address. If you want your work email to be used for a specific project rather than your personal email, that change would be added to this file.

-

description file - this file is only used by the GitWeb program, so we can ignore it

-

hooks directory - this is where we could place client-side or server-side scripts that we can use to hook into Git's different lifecycle events. Also can be used to hook into different parts or events of Git's workflow.

-

info directory - contains the global excludes file

-

objects directory - this directory will store all of the commits we make

-

refs directory - this directory holds pointers to commits (basically the "branches" and "tags")

The command is git clone and then you pass the path to the Git repository that you want to clone. An optional value could be the new name of the cloning repository you want to set. In this example, we are cloning the repo repo_to_clone and set it a new name cloned_repo

git clone https://github.com/Gonxis/repo_to_clone cloned_repo

The output of running git status in the new-git-project project:

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

The output tells us some things:

On branch master– this tells us that Git is on themasterbranch. You've got a description of a branch on your terms sheet so this is the "master" branch (which is the default branch). We'll be looking more at branches in lesson 5Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.– Because git clone was used to copy this repository from another computer, this is telling us if our project is in sync with the one we copied from. We won't be dealing with the project on the other computer, so this line can be ignored.nothing to commit, working directory clean– this is saying that there are no pending changes.

The command line git log will display by default the following:

- the SHA

- the author

- the date

- the message

It can display a lot more information than just this

When running the command line git log, will open in the terminal Less editor. Here are some helpful keys:

- to scroll down, press

- j or ↓ to move down one line at a time

- d to move by half the page screen

- f to move by a whole page screen

- to scroll up, press

- k or ↑ to move up one line at a time

- u to move by half the page screen

- b to move by a whole page screen

- press q to quit out of the log (returns to the regular command prompt)

git log --oneline

This command:

- lists one commit per line

- shows the first 7 characters of the commit's SHA

- shows the commit's message

The git log command has a flag that can be used to display the files that have been changed in the commit, as well as the number of lines that have been added or deleted. The flag is --stat ("stat" is short for "statistics")

git log --stat

This command:

- displays the file(s) that have been modified

- displays the number of lines that have been added/removed

- displays a summary line with the total number of modified files and lines that have been added/removed

The git log command has a flag that can be used to display the actual changes made to a file. The flag is --patch which can be shortened to just -p

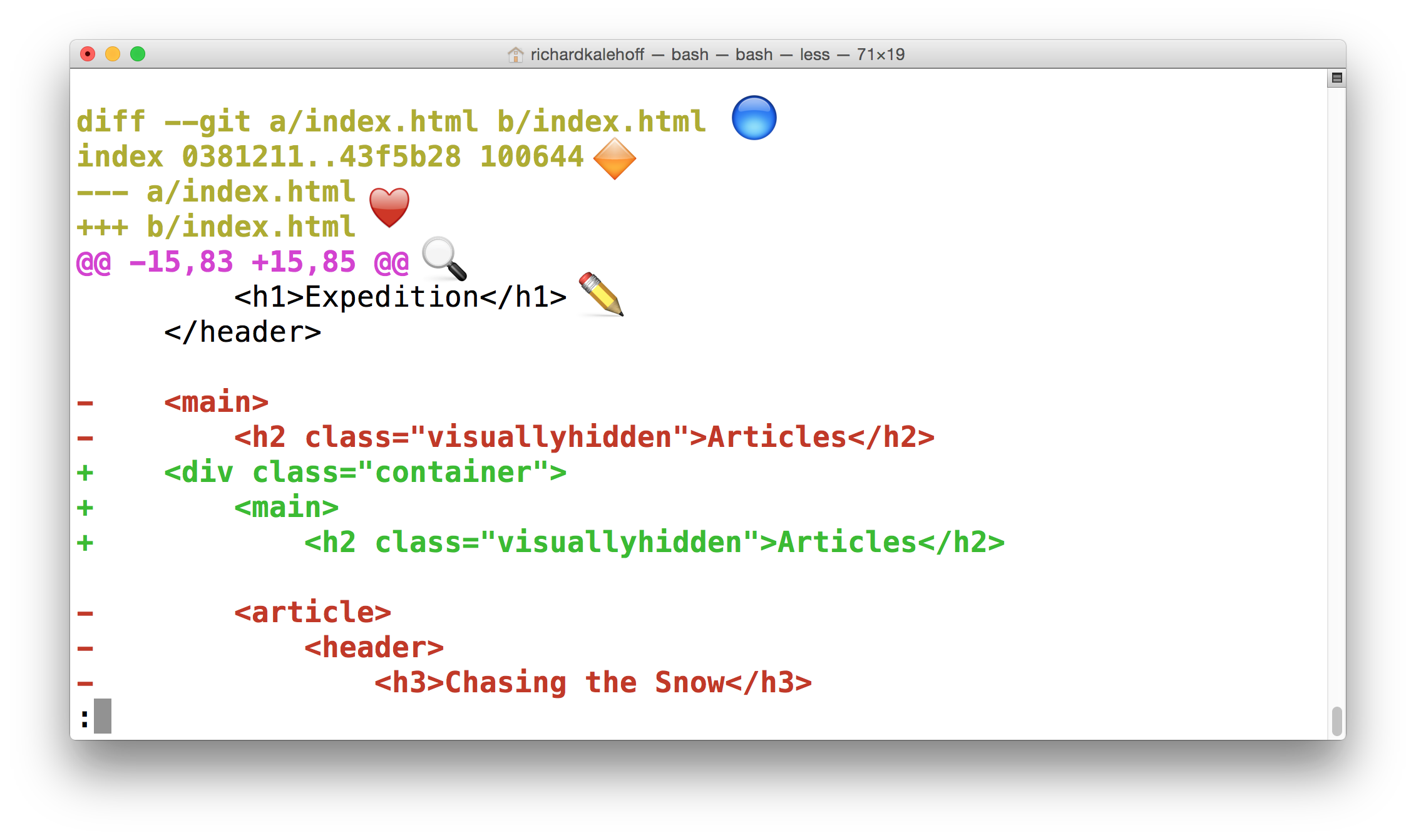

Using the image above, let's do a quick recap of the git log -p output:

- 🔵 - the file that is being displayed

- 🔶 - the hash of the first version of the file and the hash of the second version of the file

- not usually important, so it's safe to ignore

- ❤️ - the old version and current version of the file

- 🔍 - the lines where the file is added and how many lines there are

-15,83indicates that the old version (represented by the-) started at line 15 and that the file had 83 lines+15,85indicates that the current version (represented by the+) starts at line 15 and that there are now 85 lines...these 85 lines are shown in the patch below

- ✏️ - the actual changes made in the commit

- lines that are red and start with a minus (

-) were in the original version of the file but have been removed by the commit - lines that are green and start with a plus (

+) are new lines that have been added in the commit

- lines that are red and start with a minus (

$ git log --oneline --decorate --graph --all

The --graph flag adds the bullets and lines to the leftmost part of the output. This shows the actual branching that's happening. The --all flag is what displays all of the branches in the repository.

Running it like the example above will only display the most recent commit. Typically, a SHA is provided as a final argument:

$ git show fdf5493

The git show command will show only one commit. The output is exactly the same as the git log -p command. So by default, git show displays:

- the commit

- the author

- the date

- the commit message

- the patch information

However, git show can be combined with most of the other flags we've looked at:

--stat- to show the how many files were changed and the number of lines that were added/removed-por--patch- this the default, but if--statis used, the patch won't display, so pass-pto add it again-w- to ignore changes to whitespace

uses git add to add the files you want to the Staging Index:

$ git add index.html file_2 ... file_N

The git add command is used to move files from the Working Directory to the Staging Index.

$ git add <file1> <file2> … <fileN>

$ git add .

This command:

- takes a space-separated list of file names

- alternatively, the period

.can be used in place of a list of files to tell Git to add the current directory (and all nested files)

The git commit command takes files from the Staging Index and saves them in the repository.

$ git commit

This command:

- will open the code editor that is specified in your configuration

- (check out the Git configuration step from the first lesson to configure your editor)

Inside the code editor:

- a commit message must be supplied

- lines that start with a

#are comments and will not be recorded - save the file after adding a commit message

- close the editor to make the commit

Then, we use git log to review the commit we just made!

Here are some important things to think about when crafting a good commit message:

Do

- do keep the message short (less than 60-ish characters)

- do explain what the commit does (not how or why!)

Do not

- do not explain why the changes are made (more on this below)

- do not explain how the changes are made (that's what

git log -pis for!) - do not use the word "and"

- if you have to use "and", your commit message is probably doing too many changes - break the changes into separate commits

- e.g. "make the background color pink and increase the size of the sidebar"

The best way that I've found to come up with a commit message is to finish this phrase, "This commit will...". However, you finish that phrase, use that as your commit message.

The git diff command is used to see changes that have been made but haven't been committed, yet:

$ git diff

This command displays:

- the files that have been modified

- the location of the lines that have been added/removed

- the actual changes that have been made

The .gitignore file is used to tell Git about the files that Git should not track. This file should be placed in the same directory that the .git directory is in.

In the .gitignore file, you can use the following:

- blank lines can be used for spacing

#- marks line as a comment*- matches 0 or more characters?- matches 1 character[abc]- matches a, b, or c**- matches nested directories -a/**/zmatches- a/z

- a/b/z

- a/b/c/z

The command we'll be using to interact with the repository's tags is the git tag command:

$ git tag -a v1.0

with the flag -a in the command, we will be creating an annotated tag. Annotated tags are recommended because they include a lot of extra information such as:

- the person who made the tag

- the date the tag was made

- a message for the tag

If we don't provide the flag (i.e. git tag v1.0) then it'll create what's called a lightweight tag.

A Git tag can be deleted with the -d flag (for delete!) and the name of the tag:

$ git tag -d v1.0

Running git tag -a v1.0 will tag the most recent commit. But what if you wanted to tag a commit that occurred farther back in the repo's history?

All you have to do is provide the SHA of the commit you want to tag!

$ git tag -a v1.0 a87984

(after popping open a code editor to let you supply the tag's message) this command will tag the commit with the SHA a87084 with the tag v1.0.

The git branch command is used to interact with Git's branches:

$ git branch

It can be used to:

- list all branch names in the repository

- create new branches

- delete branches

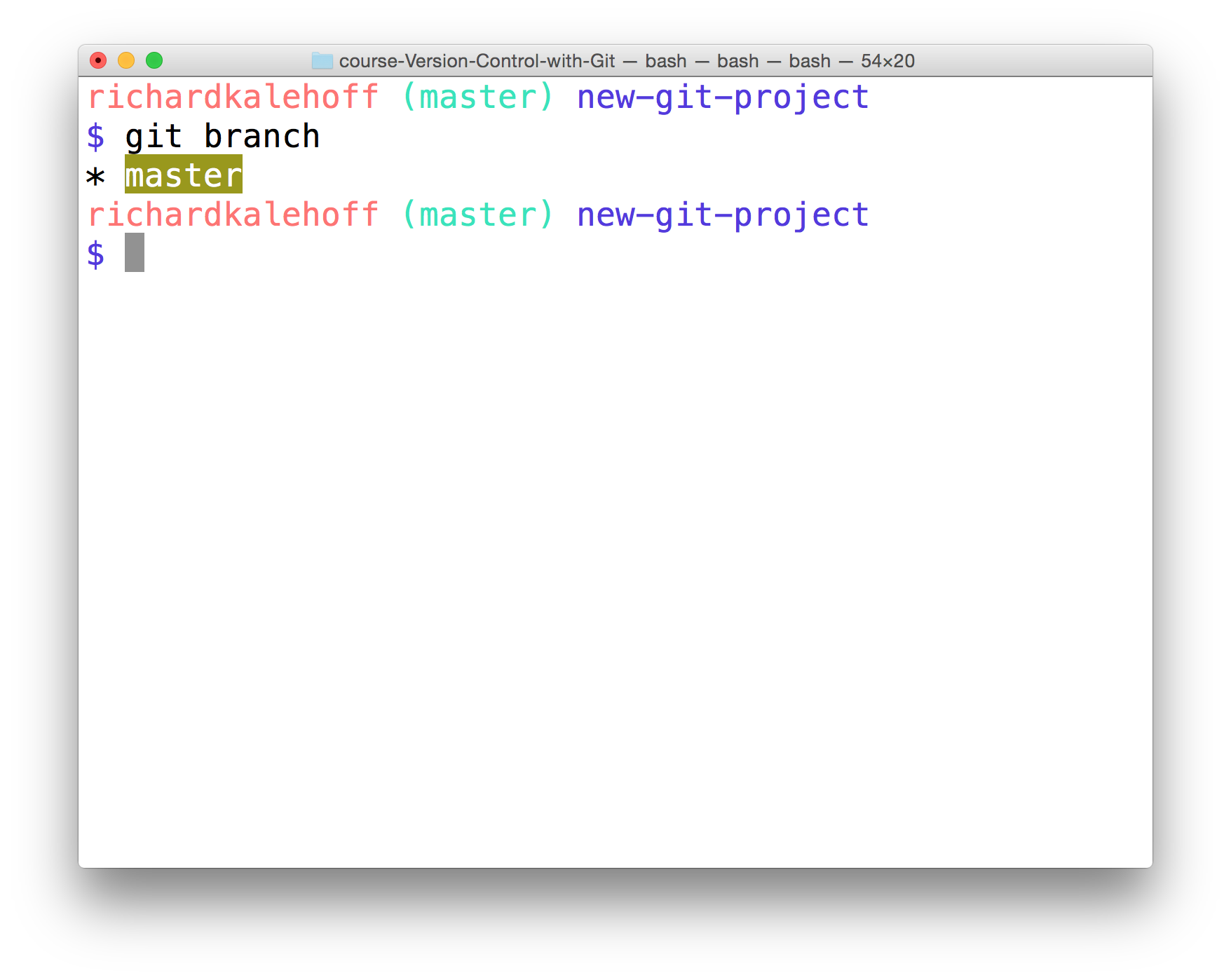

If we type out just git branch it will list out the branches in a repository:

To create a branch, all you have to do is use git branch and provide it the name of the branch you want it to create. So if you want a branch called "sidebar", you'd run this command:

$ git branch sidebar

When a commit is made that it will be added to the current branch. So even though we created the new sidebar, no new commits will be added to it since we haven't switched to it, yet. If we made a commit right now, that commit would be added to the master branch, not the sidebar branch. We've already seen this in the demo, but to switch between branches, we need to use Git's checkout command.

$ git checkout sidebar

It's important to understand how this command works. Running this command will:

- remove all files and directories from the Working Directory that Git is tracking

- (files that Git tracks are stored in the repository, so nothing is lost)

- go into the repository and pull out all of the files and directories of the commit that the branch points to

So this will remove all of the files that are referenced by commits in the master branch. It will replace them with the files that are referenced by the commits in the sidebar branch.

The fastest way to determine the active branch is to look at the output of the git branch command. An asterisk will appear next to the name of the active branch.

If we want to delete the branch, we'd use the -d flag. The command below includes the -d flag which tells Git to delete the provided branch (in this case, the "sidebar" branch).

$ git branch -d sidebar

One thing to note is that we can't delete a branch that we're currently on. So to delete the sidebar branch, we'd have to switch to either the master branch or create and switch to a new branch.

Git won't let us delete a branch if it has commits on it that aren't on any other branch (meaning the commits are unique to the branch that's about to be deleted). If we created the sidebar branch, added commits to it, and then tried to delete it with the git branch -d sidebar, Git wouldn't let us delete the branch because we can't delete a branch that we're currently on. If we switched to the master branch and tried to delete the sidebar branch, Git also wouldn't let us do that because those new commits on the sidebar branch would be lost! To force deletion, we need to use a capital D flag - git branch -D sidebar.

So, the git branch command is used to manage branches in Git:

# to list all branches

$ git branch

# to create a new "footer-fix" branch

$ git branch footer-fix

# to delete the "footer-fix" branch

$ git branch -d footer-fix

This command is used to:

- list out local branches

- create new branches

- remove branches

Here is a way to change to a new branch just created with a single command line:

$ git checkout -b new-branch-as-same-location-as-master master

The git merge command is used to combine Git branches:

$ git merge <name-of-branch-to-merge-in>

When a merge happens, Git will:

- look at the branches that it's going to merge

- look back along the branch's history to find a single commit that both branches have in their commit history

- combine the lines of code that were changed on the separate branches together

- makes a commit to record the merge

When we merge, we're merging some other branch into the current (checked-out) branch. We're not merging two branches into a new branch. We're not merging the current branch into the other branch.

Since new-branch is directly ahead of master, this merge is one of the easiest merges to do. Merging new-branch into master will cause a Fast-forward merge. A Fast-forward merge will just move the currently checked out branch forward until it points to the same commit that the other branch (in this case, new-branch) is pointing to.

To merge in the new-branch branch, run:

$ git merge new-branch

To merge in the divergent-branch branch, make sure you're on the master branch and run:

$ git merge divergent-branch

Because this combines two divergent branches, a commit is going to be made. And when a commit is made, a commit message needs to be supplied. Since this is a merge commit a default message is already supplied. It's common practice to use the default merge commit message.

Git is able to intelligently combine lots of work on different branches. However, there are times when it can't combine branches together. When a merge is performed and fails, that is called a merge conflict.

If a merge conflict does occur, Git will try to combine as much as it can, but then it will leave special markers (e.g. >>> and <<<).

A merge conflict occurs when the exact same line(s) are changed in separate branches.

The editor has the following merge conflict indicators:

<<<<<<< HEADeverything below this line (until the next indicator) shows you what's on the current branch||||||| merged common ancestorseverything below this line (until the next indicator) shows you what the original lines were=======is the end of the original lines, everything that follows (until the next indicator) is what's on the branch that's being merged in>>>>>>> heading-updateis the ending indicator of what's on the branch that's being merged in (in this case, theheading-updatebranch)

To resolve a merge conflict, we need to:

- choose which line(s) to keep

- remove all lines with indicators

The git merge command is used to combine branches in Git:

$ git merge <other-branch>

There are two types of merges:

- Fast-forward merge – the branch being merged in must be ahead of the checked out branch. The checked out branch's pointer will just be moved forward to point to the same commit as the other branch.

- the regular type of merge

- two divergent branches are combined

- a merge commit is created

With the --amend flag, you can alter the most-recent commit.

$ git commit --amend

If our Working Directory is clean (meaning there aren't any uncommitted changes in the repository), then running git commit --amend will let us provide a new commit message. Our code editor will open up and display the original commit message. Just fix a misspelling or completely reword it! Then save it and close the editor to lock in the new commit message.

Alternatively, git commit --amend will let us include files (or changes to files) we might've forgotten to include. Let's say we've updated the color of all navigation links across our entire website. We committed that change and thought we were done. But then we discovered that a special nav link buried deep on a page doesn't have the new color. We could just make a new commit that updates the color for that one link, but that would have two back-to-back commits that do practically the exact same thing (change link colors).

Instead, we can amend the last commit (the one that updated the color of all of the other links) to include this forgotten one. To do get the forgotten link included, just:

- edit the file(s)

- save the file(s)

- stage the file(s)

- and run

git commit --amend

So we'd make changes to the necessary CSS and/or HTML files to get the forgotten link styled correctly, then we'd save all of the files that were modified, then we'd use git add to stage all of the modified files (just as if we were going to make a new commit!), but then we'd run git commit --amend to update the most-recent commit instead of creating a new one.

When we tell Git to revert a specific commit, Git takes the changes that were made in commit and does the exact opposite of them.

If a character is added in commit A, if Git reverts commit A, then Git will make a new commit where that character is deleted. It also works the other way where if a character/line is removed, then reverting that commit will add that content back!

The git revert command is used to reverse a previously made commit:

$ git revert <SHA-of-commit-to-revert>

This command:

- will undo the changes that were made by the provided commit

- creates a new commit to record the change

At first glance, resetting might seem coincidentally close to reverting, but they are actually quite different. Reverting creates a new commit that reverts or undos a previous commit. Resetting, on the other hand, erases commits!

We've got to be careful with Git's resetting capabilities. This is one of the few commands that lets us erase commits from the repository. If a commit is no longer in the repository, then its content is gone.

To alleviate the stress a bit, Git does keep track of everything for about 30 days before it completely erases anything. To access this content, you'll need to use the git reflog command. Check out these links for more info:

We already know that we can reference commits by their SHA, by tags, branches, and the special HEAD pointer. Sometimes that's not enough, though. There will be times when we'll want to reference a commit relative to another commit. For example, there will be times where we'll want to tell Git about the commit that's one before the current commit...or two before the current commit. There are special characters called "Ancestry References" that we can use to tell Git about these relative references. Those characters are:

^– indicates the parent commit~– indicates the first parent commit

Here's how we can refer to previous commits:

-

the parent commit – the following indicate the parent commit of the current commit

- HEAD^

- HEAD~

- HEAD~1

-

the grandparent commit – the following indicate the grandparent commit of the current commit

- HEAD^^

- HEAD~2

-

the great-grandparent commit – the following indicate the great-grandparent commit of the current commit

- HEAD^^^

- HEAD~3

The main difference between the ^ and the ~ is when a commit is created from a merge. A merge commit has two parents. With a merge commit, the ^ reference is used to indicate the first parent of the commit while ^2 indicates the second parent. The first parent is the branch you were on when you ran git merge while the second parent is the branch that was merged in.

It's easier if we look at an example. This what my git log currently shows:

* 9ec05ca (HEAD -> master) Revert "Set page heading to "Quests & Crusades""

* db7e87a Set page heading to "Quests & Crusades"

* 796ddb0 Merge branch 'heading-update'

|\

| * 4c9749e (heading-update) Set page heading to "Crusade"

* | 0c5975a Set page heading to "Quest"

|/

* 1a56a81 Merge branch 'sidebar'

|\

| * f69811c (sidebar) Update sidebar with favorite movie

| * e6c65a6 Add new sidebar content

* | e014d91 (footer) Add links to social media

* | 209752a Improve site heading for SEO

* | 3772ab1 Set background color for page

|/

* 5bfe5e7 Add starting HTML structure

* 6fa5f34 Add .gitignore file

* a879849 Add header to blog

* 94de470 Initial commit

Let's look at how we'd refer to some of the previous commits. Since HEAD points to the 9ec05ca commit:

HEAD^is thedb7e87acommitHEAD~1is also thedb7e87acommitHEAD^^is the796ddb0commitHEAD~2is also the796ddb0commitHEAD^^^is the0c5975acommitHEAD~3is also the0c5975acommitHEAD^^^2is the4c9749ecommit (this is the grandparent's (HEAD^^) second parent (^2))

The git reset command is used to reset (erase) commits:

$ git reset <reference-to-commit>

It can be used to:

- move the HEAD and current branch pointer to the referenced commit

- erase commits

- move committed changes to the staging index

- unstage committed changes

The way that Git determines if it erases, stages previously committed changes, or unstages previously committed changes is by the flag that's used. The flags are:

--mixed--soft--hard

Let's look at each one of these flags.

* 9ec05ca (HEAD -> master) Revert "Set page heading to "Quests & Crusades""

* db7e87a Set page heading to "Quests & Crusades"

* 796ddb0 Merge branch 'heading-update'

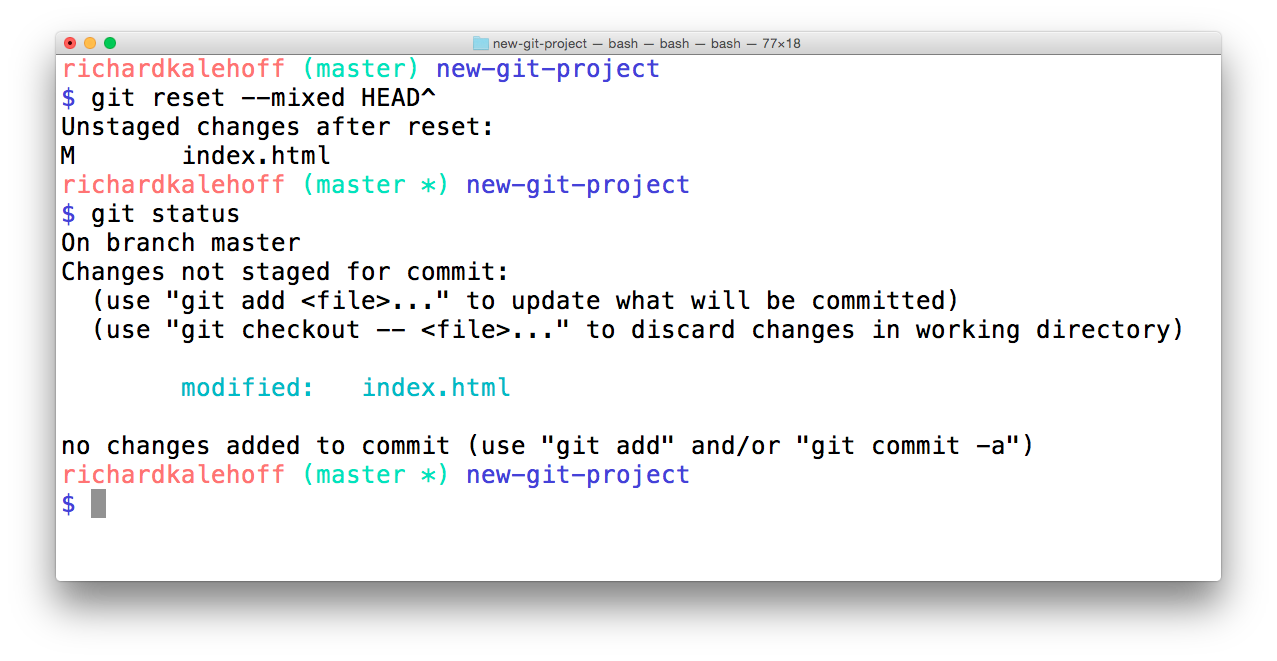

Using the sample repo above with HEAD pointing to master on commit 9ec05ca, running git reset --mixed HEAD^ will take the changes made in commit 9ec05ca and move them to the working directory.

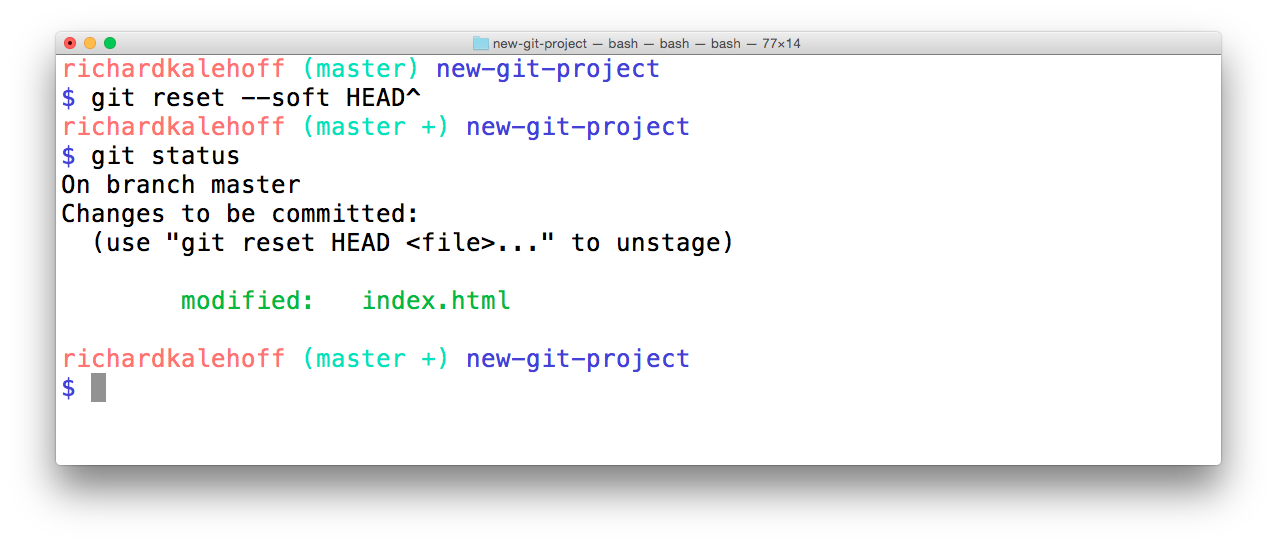

Let's use the same few commits and look at how the --soft flag works:

* 9ec05ca (HEAD -> master) Revert "Set page heading to "Quests & Crusades""

* db7e87a Set page heading to "Quests & Crusades"

* 796ddb0 Merge branch 'heading-update'

Running git reset --soft HEAD^ will take the changes made in commit 9ec05ca and move them directly to the Staging Index.

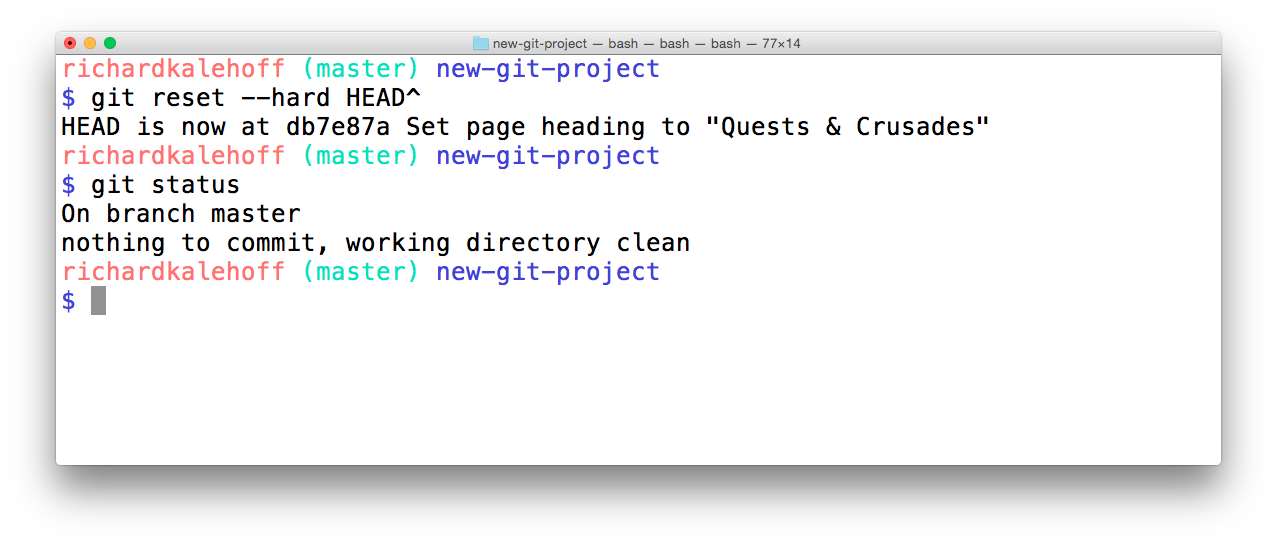

Last but not least, let's look at the --hard flag:

* 9ec05ca (HEAD -> master) Revert "Set page heading to "Quests & Crusades""

* db7e87a Set page heading to "Quests & Crusades"

* 796ddb0 Merge branch 'heading-update'

Running git reset --hard HEAD^ will take the changes made in commit 9ec05ca and erases them.

The git reset command is used erase commits:

$ git reset <reference-to-commit>

It can be used to:

- move the HEAD and current branch pointer to the referenced commit

- erase commits with the

--hardflag - moves committed changes to the staging index with the

--softflag - unstages committed changes

--mixedflag

Typically, ancestry references are used to indicate previous commits. The ancestry references are:

^– indicates the parent commit~– indicates the first parent commit

Remotes can be accessed in a couple of ways:

- with a URL

- path to a file system

Even though it's possible to create a remote repository on your file system, it's very rarely used. By far the most common way to access a remote repository is through a URL to a repository that’s out on the web.

The way we can interact and control a remote repository is through the Git remote command:

$ git remote

The git remote command will let you manage and interact with remote repositories.

If you want to see the full path to the remote repository, then all you have to do is use the -v flag

the following command is to create a connection from our local repository to the remote repository we just created on our GitHub account:

$ git remote add origin https://github.com/Gonxis/repository-for-the-project.git

There are a couple of things to notice about the command you just ran on the command line:

-

first, this command has the sub command

add -

the word

originis used - this is setting the shortname that we discussed earlier- Remember that the word

originhere isn't special in any way. - If you want to change this to

repo-on-GitHub, then (before running the command) just change the word "origin" to "repo-on-GitHub":$ git remote add repo-on-GitHub https://github.com/Gonxis/Gonxis-some-other-project.git

- Remember that the word

-

third, the full path to the repository is added (i.e. the URL to the remote repository on the web)

Now I'll use git remote -v to verify that I've added the remote repository correctly.

To send local commits to a remote repository we need to use the git push command. We provide the remote short name and then we supply the name of the branch that contains the commits we want to push:

$ git push <remote-shortname> <branch>

Our remote's shortname is origin and the commits that we want to push are on the master branch. So we'll use the following command to send our commits to the remote repository on GitHub:

$ git push origin master

There a couple of things to notice:

- Depending on how we have configured GitHub and the remote URL that's being used, we might have to enter our username and password.

- this will happen if we use the HTTP version of the remote (rather than the

sshversion) - If we have configured GitHub to use the SSH protocol and have supplied it with our SSH key then we don't need to worry about doing this step. Check the Connecting to GitHub with SSH documentation page if we're interested in using SSH with GitHub.

- this will happen if we use the HTTP version of the remote (rather than the

- If we have to enter our username and password our username will show up after typing but pur password will not. So just keep typing our password and press enter when we're done.

- If we encounter any errors with our password don't worry it'll just ask we to type it in again

- Git does some compressing of things to make it smaller and then sends those off to the remote

- A new branch is created - at the very bottom it says

[new branch]and thenmaster -> master

The branch that appears in the local repository is actually tracking a branch in the remote repository (e.g. origin/master in the local repository is called a tracking branch because it's tracking the progress of the master branch on the remote repository that has the shortname "origin").

The origin/master branch is not a live mapping of where the remote's master branch is located. If the remote's master moves, the local origin/master branch stays the same. To update this branch, we need to sync the two together.

git push will sync the remote repository with the local repository. To do the opposite (to sync the local with the remote), we need to use git pull. The format for git pull is very similar to git push - you provided the shortname for the remote repository and then the name of the branch you want to pull in the commits.

$ git pull origin master

There's several things to note about running this command:

- the format is very similar to that of

git push- there's counting and compressing and packing of items - it has the phrase "fast-forward" which means Git did a fast-forward merge (we'll dig into this in just a second)

- it displays information similar to

git log --statwhere it shows the files that have been changed and how many lines were added or removed in them

- it displays information similar to

If you don't want to automatically merge the local branch with the tracking branch then you wouldn't use git pull you would use a different command called git fetch. You might want to do this if there are commits on the repository that you don't have but there are also commits on the local repository that the remote one doesn't have either.

You can think of the git pull command as doing two things:

- fetching remote changes (which adds the commits to the local repository and moves the tracking branch to point to them)

- merging the local branch with the tracking branch

The git fetch command is just the first step. It just retrieves the commits and moves the tracking branch. It does not merge the local branch with the tracking branch. The same information provided to git pull is passed to git fetch:

- the shortname of the remote repository

- the branch with commits to retrieve

$ git fetch origin master

Trying to run the git fork command produces an error. (Also, fsck is not a rude word, it means "filesystem check" and refers to auditing the files for consistency.)

If a repository doesn't belong to our account then it means we do not have permission to modify it.

This is where forking comes in! Instead of modifying the original repository directly, if we fork the repository to our own account then we will have full control over that repository.

Forking is an action that's done on a hosting service, like GitHub. Forking a repository creates an identical copy of the original repository and moves this copy to our account. You have total control over this forked repository. Modifying our forked repository does not alter the original repository in any way.

A way that we can see how many commits each contributor has added to the repository is to use the git shortlog command:

$ git shortlog

git shortlog displays an alphabetical list of names and the commit messages that go along with them. If we just want to see just the number of commits that each developer has made, we can add a couple of flags: -s to show just the number of commits (rather than each commit's message) and -n to sort them numerically (rather than alphabetically by author name).

$ git shortlog -s -n

Another way that we can display all of the commits by an author is to use the regular git log command but include the --author flag to filter the commits to the provided author.

$ git log --author=Surma

The git log command is extremely powerful, and you can use it to discover a lot about a repository. But it can be especially helpful to discover information about a repository that you're collaborating on with others. You can use git log to:

-

group commits by author with

git shortlog$ git shortlog -

filter commits with the

--authorflag$ git log --author="Richard Kalehoff" -

filter commits using the

--grepflag$ git log --grep="border radius issue in Safari"

grep is a complicated topic and you can find out more about it here on the Wiki page.

While we're talking about naming branches clearly that describe what changes the branch contains, I need to throw in another reminder about how critical it is to write clear, descriptive, commit messages. The more descriptive your branch name and commit messages are the more likely it is that the project's maintainer will not have to ask you questions about the purpose of your code or have dig into the code themselves. The less work the maintainer has to do, the faster they'll include your changes into the project.

This has been stressed numerous times before but make sure when you are committing changes to the project that you make smaller commits. Don't make massive commits that record 10+ file changes and changes to hundreds of lines of code. You want to make smaller, more frequent commits that record just a handful of file changes with a smaller number of line changes.

Think about it this way: if the developer does not like a portion of the changes you're adding to a massive commit, there's no way for them to say, "I like commit A, but just not the part where you change the sidebar's background color." A commit can't be broken down into smaller chunks, so make sure your commits are in small enough chunks and that each commit is focused on altering just one thing. This way the maintainer can say I like commits A, B, C, D, and F but not commit E.

And lastly if any of the code changes that you're adding drastically changes the project you should update the README file to instruct others about this change.

Before we start doing any work, make sure to look for the project's CONTRIBUTING.md file.

Next, it's a good idea to look at the GitHub issues for the project

- look at the existing issues to see if one is similar to the change we want to contribute

- if necessary create a new issue

- communicate the changes we'd like to make to the project maintainer in the issue

When we start developing, commit all of our work on a topic branch:

- do not work on the master branch

- make sure to give the topic branch clear, descriptive name

As a general best practice for writing commits:

- make frequent, smaller commits

- use clear and descriptive commit messages

- update the README file, if necessary

A pull request is a request to the original or source repository's maintainer to include changes in their project that you made in your fork of their project. You are requesting that they pull in changes you've made.

A pull request is a request for the source repository to pull in your commits and merge them with their project. To create a pull request, a couple of things need to happen:

- you must fork the source repository

- clone your fork down to your machine

- make some commits (ideally on a topic branch!)

- push the commits back to your fork

- create a new pull request and choose the branch that has your new commits

If we want to keep up-to-date with the Repository, GitHub offers a convenient way to keep track of repositories - it lets you star repositories.

Starring is helpful if we want to keep track of certain repositories. But it's not entirely helpful if we need to actively keep up with a repositories development because we have to manually go to the stars page to view the repositories and see if they've changed.

If you need to keep up with a project's changes and want to be notified of when things change, GitHub offers a "Watch" feature.

If we're working on a repository quite often, then I'd suggest setting the watch setting to "Watching". This way GitHub will notify us whenever anything happens with the repository like people pushing changes to the repository, new issues being created, or comments being added to existing issues.

Incase Lam starts making changes to her project that I won't have in my fork of her project, I'll add her project as an additional remote so that I can stay in sync with her.

In my local repository, I already have one remote repository which is origin remote.

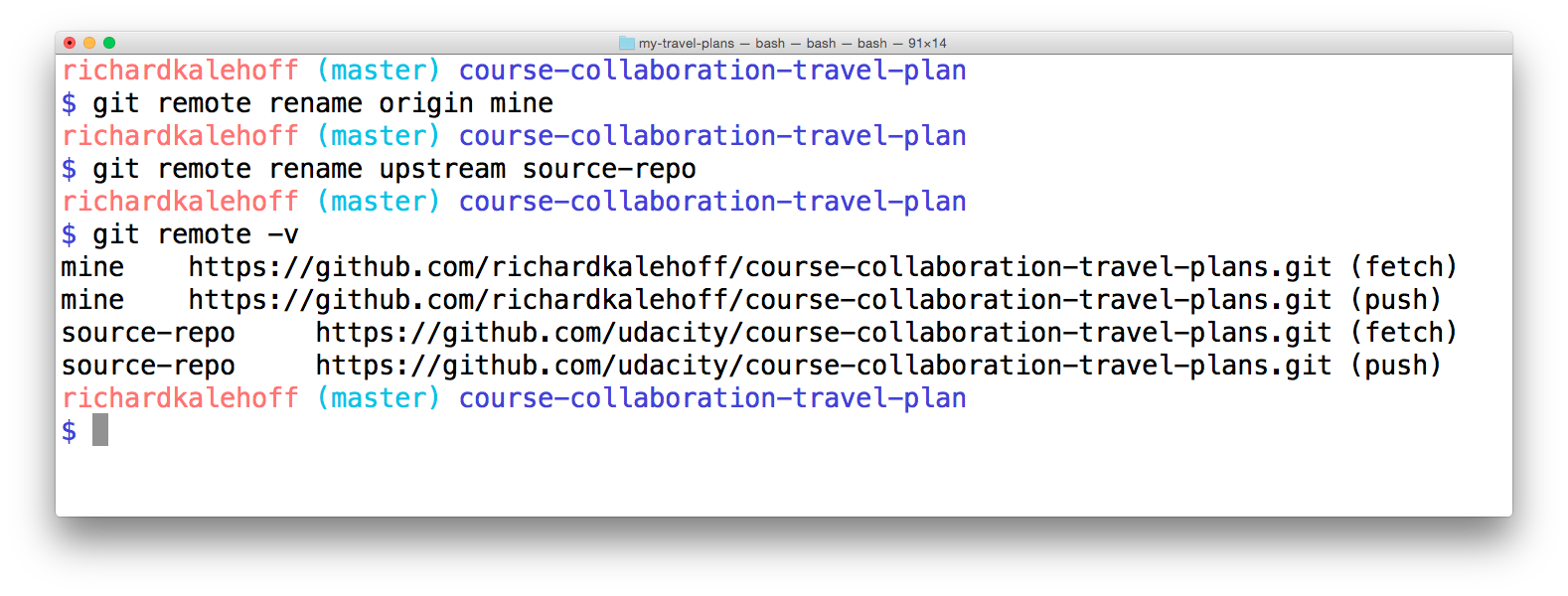

Remember that the word origin is just the default name that's used when you git clone a remote repository for the first time. We're going to use the git remote command to add a new shortname and URL to this list. This will give us a connection to the source repository.

$ git remote add upstream https://github.com/Gonxis/some-random-project.git

One thing that can be a tiny bit confusing right now is the difference between the origin and upstream. What might be confusing is that origin does not refer to the source repository (also known as the "original" repository) that we forked from. Instead, it's pointing to our forked repository. So even though it has the word origin is not actually the original repository.

Remember that the names origin and upstream are just the default or de facto names that are used. If it's clearer for you to name your origin remote mine and the upstream remote source-repo, then by all means, go ahead and rename them. What you name your remote repositories in your local repository does not affect the source repository at all.

When working with a project that you've forked. The original project's maintainer will continue adding changes to their project. You'll want to keep your fork of their project in sync with theirs so that you can include any changes they make.

To get commits from a source repository into your forked repository on GitHub you need to:

- get the cloneable URL of the source repository

- create a new remote with the

git remote addcommand- use the shortname

upstreamto point to the source repository - provide the URL of the source repository

- use the shortname

- fetch the new

upstreamremote - merge the

upstream's branch into a local branch - push the newly updated local branch to your

originrepo

When you submit a pull request, remember that you're asking another developer to add your code changes to their project. If they ask you to make some minor (even major!) changes to your pull request, that doesn't mean they're rejecting your work! It just means that they would like the code added to their project in a certain way.

The CONTRIBUTING.md file should be used to list out all information that the project's maintainer wants, so make sure to follow the information there. But that doesn't mean there might be times where the project's maintainer will ask you to do a few additional things.

So what should you do? Well, if you want your pull request to be accepted, then you make the change! Remember that the tab in GitHub is called the "Conversation" tab. So feel free to communicate back and forth with the project's maintainer to clarify exactly what they want you to do.

It also wouldn't hurt to thank them for taking the time to look over your pull request. Most of the developers that are working on open source projects are doing it unpaid. So remember to:

- be kind - the project's maintainer is a regular person just like you

- be patient - they will respond as soon as they are able

As simple as at may seem, working on an active pull request is mostly about communication!

If the project's maintainer is requesting changes to the pull request, then:

- make any necessary commits on the same branch in your local repository that your pull request is based on

- push the branch to the your fork of the source repository The commits will then show up on the pull request page.

Let's take another look at the different commands that you can do with git rebase:

- use

porpick– to keep the commit as is - use

rorreword– to keep the commit's content but alter the commit message - use

eoredit– to keep the commit's content but stop before committing so that you can:- add new content or files

- remove content or files

- alter the content that was going to be committed

- use

sorsquash– to combine this commit's changes into the previous commit (the commit above it in the list) - use

forfixup– to combine this commit's change into the previous one but drop the commit message - use

xorexec– to run a shell command - use

dordrop– to delete the commit

As you've seen, the git rebase command is incredibly powerful. It can help you edit commit messages, reorder commits, combine commits, etc. So it truly is a powerhouse of a tool. Now the question becomes "When should you rebase?".

Whenever you rebase commits, Git will create a new SHA for each commit! This has drastic implications. To Git, the SHA is the identifier for a commit, so a different identifier means it's a different commit, regardless if the content has changed at all.

So you should not rebase if you have already pushed the commits you want to rebase. If you're collaborating with other developers, then they might already be working with the commits you've pushed. If you then use git rebase to change things around and then force push the commits, then the other developers will now be out of sync with the remote repository. They will have to do some complicated surgery to their Git repository to get their repo back in a working state...and it might not even be possible for them to do that; they might just have to scrap all of their work and start over with your newly-rebased, force-pushed commits.

The git rebase command is used to do a great many things.

# interactive rebase

$ git rebase -i <base>

# interactively rebase the commits to the one that's 3 before the one we're on

$ git rebase -i HEAD~3

Inside the interactive list of commits, all commits start out as pick, but you can swap that out with one of the other commands (reword, edit, squash, fixup, exec, and drop).

I recommend that you create a backup branch before rebasing, so that it's easy to return to your previous state. If you're happy with the rebase, then you can just delete the backup branch!