- Cross-Application Communication

- HTTP Request / Response Cycle

- The

fetch()function - Digging Deeper into Fetching

Okay now we’re really getting somewhere. So far we’ve been writing programs that consist ENTIRELY of code that we write (or download via npm). Now, we will enter the world of

A web application's most common asynchronous operation is requesting data from another computer. For example:

- User can see the current weather.

- My application can request that data from a Weather API.

- User can use a Google map.

- My application can request that map from the Google Maps API

- User can generate random pictures of dogs on the internet.

- My application can request those images from the dog api

This is an example of user stories and criteria for success. More on that later. If you need to know now check this out (

HTTP stands for Hypertext Transfer Protocol. It is the standard for communication over the internet. (Well HTTPS, the “secure” version, is now the standard).

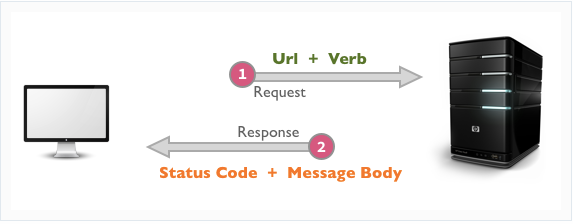

The HTTP Request/Response cycle is the pattern of communication used by two computers communicating using the HTTP protocol. It works like this:

- The program/computer making the request is the client

- The client must initiate a request. A server can’t reach out and send Responses to clients on its own. It just waits for incoming requests.

- That program/computer responding to the request is called the server

- The server must already be up and running and ready to accept incoming requests.

- The request and response sent between the client and server each contain important information including:

- The request URL of the specific requested resource

- The request verb — what it wants the server to do (post something new, send back some data, update or delete something)

- The response status code (did the request succeed?)

- The response body (the data sent back to the client)

Try using this code in

fetchNewDogfunction found in the0-fetching-demo-start/js/event-helpers.jsfile

fetch(url) is a function that sends a request to a server.

- It is available in browsers and in Node!

- Its only required argument is a URL of the API whose data we want to access.

- It is assumed that the request verb is GET.

fetch()returns aPromisecontaining the HTTP Response.

const fetchPromise = fetch('https://dog.ceo/api/breeds/image/random');

console.log("look, its a promise!:", fetchPromise);

fetchPromise.then((response) => {

console.log(response.url)

console.log(response.ok)

console.log(response.status)

console.log(response.statusText)

console.log(response.body)

});fetch() returns a Promise whose resulting value is the response object. The response object's url, ok and status properties are all useful information. The ok and status properties immediately tell us if our request was successful and, if not, why.

const fetchPromise = fetch('https://dog.ceo/api/breeds/image/random');

fetchPromise.then((response) => {

if (!response.ok) {

return console.log(`Failed response. ${response.status} ${response.statusText}`)

}

console.log(`The request to ${response.url} was successful!`);

console.log("Here is your data:", response.body);

});However, the response.body is a ReadableStream object. We need to do something else to access the data in that stream.

To access the data from the response body, we need to parse it, which is another asynchronous operation. Below, you'll see how we've nested these asynchronous operations:

// 1. Perform the fetch

fetch('https://dog.ceo/api/breeds/image/random')

.then((response) => {

// 2. Check if the response is ok before proceeding

if (!response.ok) {

return console.log(`Failed response. ${response.status} ${response.statusText}`)

}

// This log isn't necessary but its nice for testing

console.log(`The request to ${response.url} was successful!`);

// 3. Parse the body of the response. `response.json()` also returns a Promise that we should handle using `.then`

response.json()

.then((responseData) => {

console.log("Here is your data:", responseData);

// 4. Render the data to the screen using DOM manipulation

});

})- The

responseobject has a.json()method which parses the body of the response as JSON. response.json()is also asynchronous and returns a Promise that resolves to the response body.- Once the data is parsed, we can then use it (print it, render it, etc…)

Here we are using the API from https://dog.ceo/ and the specific “endpoint” URL https://dog.ceo/api/breeds/image/random. Try these other APIs:

- https://dog.ceo/api/breed/hound/images

- https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon/pikachu

- https://v2.jokeapi.dev/joke/Programming

- https://api.sunrise-sunset.org/json?lat=36.7201600&lng=-4.4203400&date=2023-3-15

Rather than nesting the promise handling, we often will chain them together instead:

fetch('https://dog.ceo/api/breeds/image/random')

.then((response) => {

if (!response.ok) {

return console.log(`Failed response. ${response.status} ${response.statusText}`)

}

// We can return a promise from `.then` to create a chain of `.then`s

// The next `.then` callback will receive the resolved value of this Promise

return response.json()

})

.then((responseData) => {

console.log("Here is your data:", responseData);

// do something with the response data

});This works because .then will returns a Promise that resolves to the value its callback returns.

If the .then callback itself returns a Promise, the promise returned by .then will be the same Promise returned by its callback.

In other words, .then will first check to see what the callback returns. If it is a non-Promise value, it will wrap that value in a Promise. If it is a Promise, it will just return that Promise.

Remember that all Promises will either resolve or reject. Resolved Promises trigger the .then callback to be invoked while rejected Promises trigger the catch() callback to be invoked.

Since fetching involves two promises (fetching first, then parsing the response body), we should be aware of what can cause those rejections:

- A

fetch()Promise rejects when the request itself fails. For example, the URL might be malformed (hxxp://example.com) or there is a network error (you don't have internet). This is different from the response errors you might get depending on the HTTP status code - A

response.json()Promise rejects when theresponsebody is NOT in JSON format and therefore cannot be parsed.

When chaining together multiple promises, if either of the Promises returned by fetch() or response.json() reject, both can be handled by a single .catch():

fetch('https://dog.ceo/api/breeds/image/random')

.then((response) => {

if (!response.ok) {

return console.log(`Fetch failed. ${response.status} ${response.statusText}`)

}

return response.json()

})

.then((responseData) => {

console.log("Here is your data:", responseData);

// do something with the response data

})

.catch((error) => {

console.log("Error caught!");

console.error(error.message);

})- Note that A

fetch()promise does not reject if the server responds with HTTP status codes that indicate errors (404, 504, etc...).- You can see that the

!response.okguard clause will execute when you send a request to an API url that doesn't exist (try removing the/randompart of the URL) - However, if you mess up the URL (replace

httpwithhxxp) then an error is thrown and the.catch()callback will be executed

- You can see that the

Every Response that we receive from a server will include a status code indicating how the request was processed. Was the resource found and returned? Was the resource not found? What there an error? Did the POST request successfully create a new resource?

Responses are grouped in five classes:

- Informational responses (100 – 199)

- Successful responses (200 – 299)

- Redirection messages (300 – 399)

- Client error responses (400 – 499)

- Server error responses (500 – 599)

Important ones to know are 200, 201, 204, 404, and 500

Every URL has a few parts. Understanding those parts can help us fetch precisely the data we want.

Consider this URL which tells us information about the sunrise and sunset at a particular latitude and longitude:

https://api.sunrise-sunset.org/json?lat=36.7201600&lng=-4.4203400&date=2023-3-15

Let's break it down:

https://api.sunrise-sunset.org— This is the host. It tells the client where the resource is hosted/located./json- This is the path. It shows what resource is being requested?lat=36.7201600&lng=-4.4203400&date=2023-3-15- These are query parameters and this particular URL has 3:lat,lng, anddate. Query parameters begin with a?are are separated with&. Each parameter uses the formatname=value. Try changing thedateparameter!

When using a new API, make sure to look at that APIs documentation (often found at the host address) to understand how to format the request URL.

HTTP requests can be made for a variety of purposes. Consider these examples related to Instagram:

- The client requests to see all posts made by Beyonce (Read)

- The client requests to post a new picture on their profile (Create)

- The client requests to update a post they made yesterday (Update)

- The client requests to delete a post they made yesterday (Delete)

Each of these actions has an HTTP verb that is associated with it.

GET- ReadPOST- CreatePATCH- UpdateDELETE- Delete

This HTTP verb or “method” is sent in the HTTP Request so that the server knows what kind of request it is receiving.

The default behavior of using fetch is to make a GET request, but we can also make other kinds of requests by adding a second options argument to fetch():

const newUser = { name: "morpheus", job: "leader" };

const updateUser = {name: "neo", job: "leader"}

const postOption = {

method: "POST", // The type of HTTP request

body: JSON.stringify(newUser), // The data to be sent to the API

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json" // The format of the body's data

}

}

// This is a good API to practice GET/POST/PATCH/DELETE requests

const url = 'https://reqres.in/api/users';

// Notice that the options object is provided as the second arg

fetch(url, postOption)

.then((response) => {

if (!response.ok) {

return console.log(`Fetch failed. ${response.status} ${response.statusText}`)

}

return response.json();

})

.then((responseData) => {

// A POST request will return the object created with an id and a createdAt timestamp

console.log("Here is your data:", responseData);

})

.catch((error) => {

console.log("Error caught!");

console.error(error.message);

})Most of the options object is boilerplate (it's mostly the same each time):

- The

methoddetermines the kind of request - The

bodydetermines what we send to the server. Note that it must beJSON.stringify()-ed first. - The

headersobject provides meta-data about the request. It can provide many pieces of information but here all we need to share is the format of the data we are sending to the API.

The url used here is from https://reqres.in which is a great "dummy" API that you can use to practice making various kinds of fetch requests.