To be able to have two nodes in the same computer you should run run_market.py with 3 arguments which have to be different for each node.

For example:

python run_market.py 8080 /home/bunetz/.Tribler /home/bunetz/.Tribler/ec_multichain.pem

python run_market.py 8082 /home/bunetz/.Tribler2 /home/bunetz/.Tribler2/ec_multichain2.pem

Now we can call the API deployed in http://localhost:[port], for this we can use the index.html file for the GUI.

To use IPFS we can use the following page: http://54.196.97.107/ which is running the code inside IPFS/broswer-browserify with the following command:

npm start

Market API documentation https://tribler.readthedocs.io/en/devel/restapi/market.html

We make use of submodules, so remember using the --recursive argument when cloning this repo.

We support development on Linux, macOS and Windows. We have written documentation that guides you through installing the required packages when setting up a Tribler development environment. See our Linux development guide http://tribler.readthedocs.io/en/devel/development/development_on_linux.html for the guide on setting up a development environment on Linux distributions. See our Windows development guide http://tribler.readthedocs.io/en/devel/development/development_on_windows.html for setting everything up on Windows. See our OS X development guide http://tribler.readthedocs.io/en/devel/development/development_on_osx.html for the guide to setup the development environment on macOS.

First clone the repository:

git clone --recursive git@github.com:Guillembonet/EDMP.git

or, if you haven't added your ssh key to your github account:

git clone --recursive https://github.com/Guillembonet/EDMP.git

Second, install the dependencies <doc/development/development_on_linux.rst>_.

Done! Now you can run the market with the instructions above.

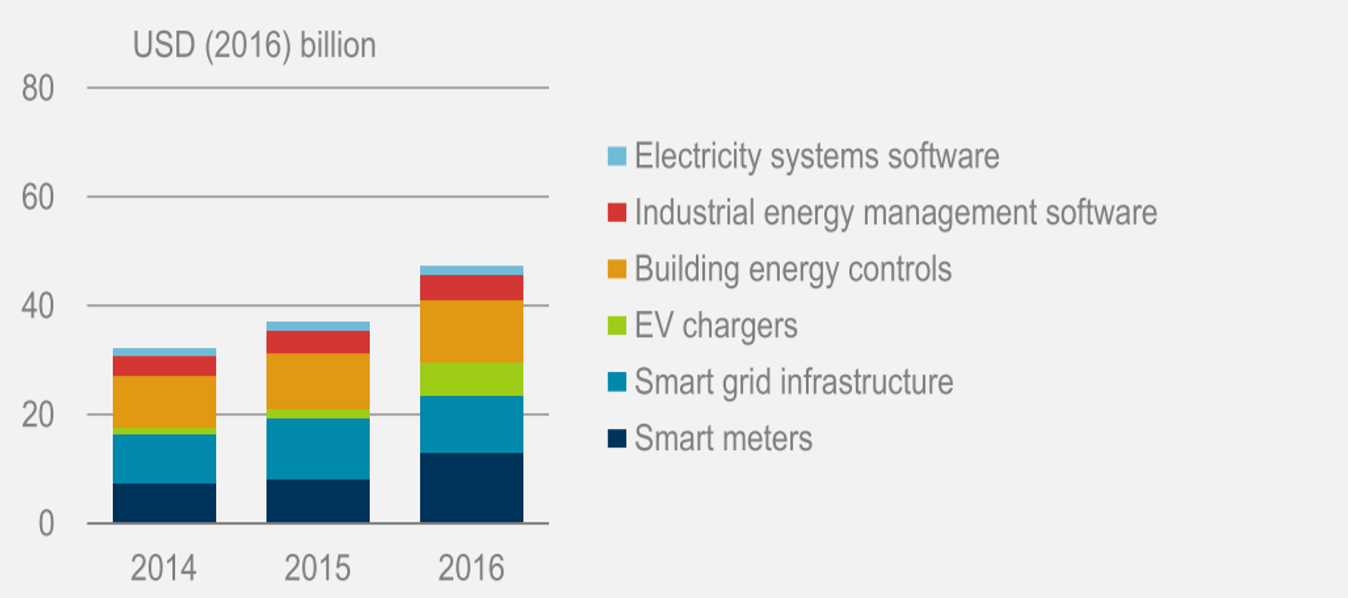

Nowadays some main transformations are happening in the energetic scenario. The one that will represent a significant change is the electrification of the energy system (1). Industry 4.0, electric vehicle (EV), heat pumps, new appliances and other trends are shifting energy demand towards a more electric system. Is clear that the electric system will face a tremendous growth, but this situation is complicated by the fact that the system will become more complex and will face disruptive organisational evolution. The introduction of unpredictable renewable energy sources (RES), generation of enormous amounts of valuable data both from the supply and the demand side, decentralisation of energy generation and its distribution are only a few of the changes that will affect the system. On top of that, a solution is envisioned in the digitalisation of the electricity infrastructure (2). This option will come with both advantages and risk so is up to us to design a resilient, secure and smart scheme able to face future challenges. This trend is not merely made up of one technological solution, but is composed of a myriad of different approaches with a varied degree of interlinking and with the possibility of overlapping one to another. However, the main point is that the direction is nowadays clear as the image demonstrate. In fact, the constant growth in the last year of more than 20% in digital electricity infrastructures, make this side of the electricity system overtake other important sides as the investment in the global overall gas-fired power generation. This physical infrastructure will need platforms able to foster and protect stakeholder participation securely and safely. This is where new solutions, coming from the computer science realm, will make the difference. Machine learning will play a central role in DSM (demand-side management) enabling the possibility of acquiring valuable data and built upon them new solution, automation will be a crucial player in more efficient EV charging infrastructure and electricity flow management but we strongly think that DLT (distributed ledger technology) will be a fundamental part of the next smart-grid (3).

Is now clear that the entanglement between DLT or blockchain tech and the electricity system is prone to become stronger. Is not the aim of this work to list all the different and numerous advantages of this relation but is worth to mention only some: L03 located in the US is involved in the field of decentralized energy treading (4) it is based on Tendermint platform and it is exploiting a Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance consensus algorithm, Power Ledger (5) is focused on different issues such as management, carbon trading and e-mobility and it is based on Ethereum platform thus using a PoW consensus algorithm, BlockLab (6) is based in the Netherlands and it is focused in energy metering.

The benefits that this technology, with many different variants, will bring are directed towards different fields as it is possible to understand from above. Financial, management, decentralisation, simplification of the infrastructure, elimination of useless third party, data ownership, privacy and many others are the aspect that blockchain technology will influence. Of course, it is not the aim of four TU Delft students to analyse and solve all of them, but we aim in trying to start proposing a solution for addressing some pre-existing issues.

The Economist started an article with: “The world’s most valuable resource it is no longer oil, but data” (7). This subject is hugely vast, but it is cardinal to understand that data play a central role also in the energy sector. It was already demonstrated, how the usage of data could if coupled with machine learning, strongly benefit the electricity consumption, when Google in 2016 in collaboration with DeepMind, reduced the energy demand of its data centre by 40% (8). The utilisation of energy demand data will lower total energy consumption, will help to achieve more than 185 GW of flexibility (the summed power demand of all Italy and Australia) and cut expenses of around 270 billion$, and it will reduce emissions [2]. These benefits in economic terms will not be unilateral if the system will be accurately designed. Firms will cut cost, new business as energy services companies could flourish through the processing of an accessible source of raw data, and finally, participation and rewarding of end consumer must also be appropriately addressed.

As shown in Figure 1 smart meter (SM) is one of the physical digital energy infrastructures with higher investment nowadays. Their cost is sharply decreasing, with global deployment of circa 600 million devices (2).

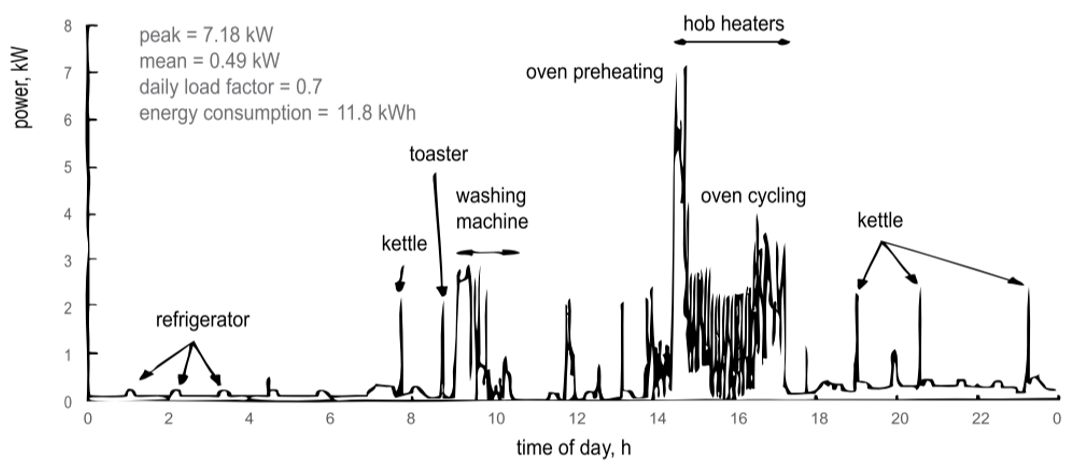

SMs primarily work by digitally reading energetic consumptions of buildings in kWh of electricity and gas and then generating ready-made data. Without going into detail is so bright that they will play a central role in understanding and exploiting demand pattern.

Buildings, in fact, account for nearly 55% of global electricity consumption and 1/3 of global energy demand. This sector moreover is the one with the highest potential in reaping the benefits of using data to implement DSM machine learning solutions.

However, this image is not that spick-and-span. There are some problems related to data acquisition.

First, newly generated data are necessary. The advantage in analysing a large set of data coming from SM devices is essential especially when deep learning is exploited. Even if the amount necessary is debatable, as in an interesting GitHub post is discussed (9), it is clear that newly generated data comes with great value. The International Energy Agency says: “Difficulties in obtaining data may also present a significant barrier to using digital technologies to improve the planning of power systems.” (2). For this reason, a method, in order to foster data sharing and rewarding for this action, must be put in place.

Secondly, energy usage data are strongly related to privacy. As Figure 2 shows, they could reveal personal daily routines and also be used for criminal activity. Therefore, Opt-in regulation programs require that consumer must give personal authorisation for SM data usage. Moreover, GDPR policy requires consumer privacy protection; possibility could be pseudonymise or complete anonymity, plus the possibility for clients to specifically consent the usage of their data.

Finally, central data management already showed its wretched characteristics. It is not only the infamous problem of a single failure point, but also the fact that central authorities are expensive to maintain and to support financially. DCC ( Data Communication Company) in the UK, the company with the task of centralising SM’s data, already showed many time its expensive and inefficient infrastructure (10) (11) (12) (13).

Developing the project that sees us involved in the Blockchain Engineering class, we want to propose a starting solution for the problem mentioned above. This solution comes with the idea of creating a decentralised market, without central authority control, that will enable people consensus in sharing their energy data, and that will ensure participation by applying a reward to the action of providing these data in the form of payment processed by the data user. As is evident this solution, even if in a primitive form, aim to solve the three-problem highlighted above. The central core of this solution is the exploitation of DLT by using TrustChain, a blockchain platform developed at TU Delft in a previous work by Pim Otte, Martijn de Vos, Johan Pouwelse (14). We will see on how TrustChain has a series of particular technical characteristics that put it as a more valuable answer if compared with other blockchain solution. We will give more details about how our architecture is designed, how it works and how it is implemented.

TrustChain is described as a: “A Sybil-resistant scalable blockchain”. It was already exploited in the creation of decentralised segmented market (15), something similar to the SM’s data one, and so it perfectly fit our case study. We will not go through an in-depth technical description of the blockchain design, but it is helpful to enlist some main characteristics that make TrustChain a valuable solution. As the reader surely knows, essentially blockchain is a data structure, built on a P2P decentralised network, able to securely records, in a tamper-proof way, the passage of “something” of value from owner to owner. Basically, DLT establishes the validity of transaction between users. This “something” could be any kind of digital assets. In 2009 this “something” was cryptocurrency specifically Bitcoin, and subsequently all the following altcoin. However, as already highlighted DLT could record the passage of other digital assets as file, video or energy consumption data. Normally blockchain architecture contemplates a central transaction chain settled by all users, using a predetermined protocol able to select on which transaction history users agree. This mechanism prevents some issues like double spending and is resilient to attack like the Sybil one. This last problem is related to the fact that there is no correspondence between physical and digital identity, because a single individual could detain multiple digital profiles. For this reason, a simple voting system is not safe since some individual could have higher and unfair voting weight only because they detain multiple digital correspondences. Standard blockchain architectures avoid this problem relating digital identity to physical property as computational power and energy consumption through a PoW mechanism. Even if useful this method is resource intensive, and specifically, it requires electricity consumption to solve a difficult computational puzzle in order to add a new block to the blockchain. The reader could immediately understand that an electricity intense mechanism is not smart to use in order to solve a problem directly related to energy consumption; moreover all other traditional blockchain require, even if in a different form, other types of consensus mechanism that compromise scalability and the possibility of performing parallel transactions. With the strong global deployment of SM depicted above scalability could be an issue with also the necessity of performing multiple parallel transactions. So, the question is: “Is there a solution able to tackle down these problems?” The answer is: TrustChain. The authors would like to use the same words of Otte et al. in (14): “In contrast to many existing blockchain architectures which attempt to prevent fraudulent operations like double spending, we aim for a guarantee that fraud can be detected, even after it has been committed already. Not actively preventing fraud allows us to drop the requirement for global consensus while tremendously improving scalability due to the possibility of transactions per-formed in parallel.”

The image below mainly represents TrustChain architecture. Each user detains his chain and each block store a single transaction signed by two users (asker and bidder) (following works expand this possibility with multiple users (15)). Moreover, each block has two different incoming pointers to both transaction parties previous block. This unique characteristic makes TrustChain more secure because it avoids that single agents maintain only their own chain with the possibility of illegal behaviour since lack of counterparties control.

This original design avoids the necessity of consensus algorithm cause rather than prevent it detects fraud. The entire community runs fraud detection by checking block that users are obliged to gossip through a flooding mechanism.

In such architecture, a scoring system NetFlow is used to assess user trustiness history and their participation. Is really interesting to use this accounting mechanism used in Tribler by evaluating consumers engagement in the community. Even if not evaluated here, this system seems really effective in evaluating people commitment in an Energy Community by evaluating their participation in making the system better by sharing a higher amount of data. Further investigation of NetFlow benefices could be assessed in impact on Energy Community initiatives.

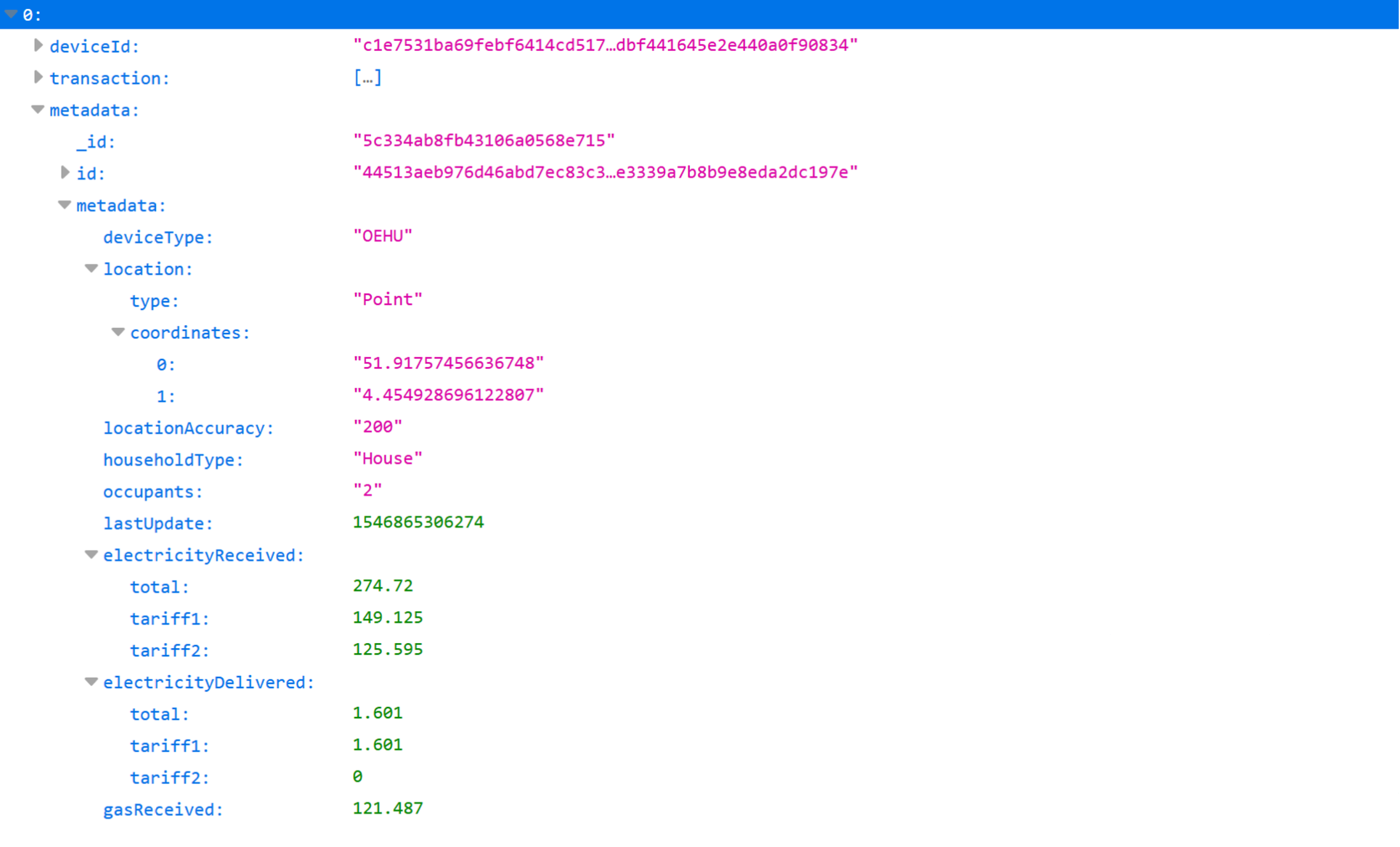

We will now present the design of our energy data decentralised market that is built upon TrustChain structure. We used the open access code of Tribler provided in GitHub to create an architecture suitable for our purposes. The source of data is coming from a Raspberry Pi device directly connected to the meter. The data are then uploaded to a http link that we used in order to gather this data as overall consumption of energy in the form of electricity (kWh) and gas (m3). OEHU (16), developed by BlockLab, is the provider of the open source database to store this data. Our idea comes into action once the data are collected. Basically, we start developing an environment where each user could get credit in the form of a token to be rewarded by his own data, generated throughout the day by using: the oven, watching TV, cooking or exploiting other appliances that run on electricity or gas.

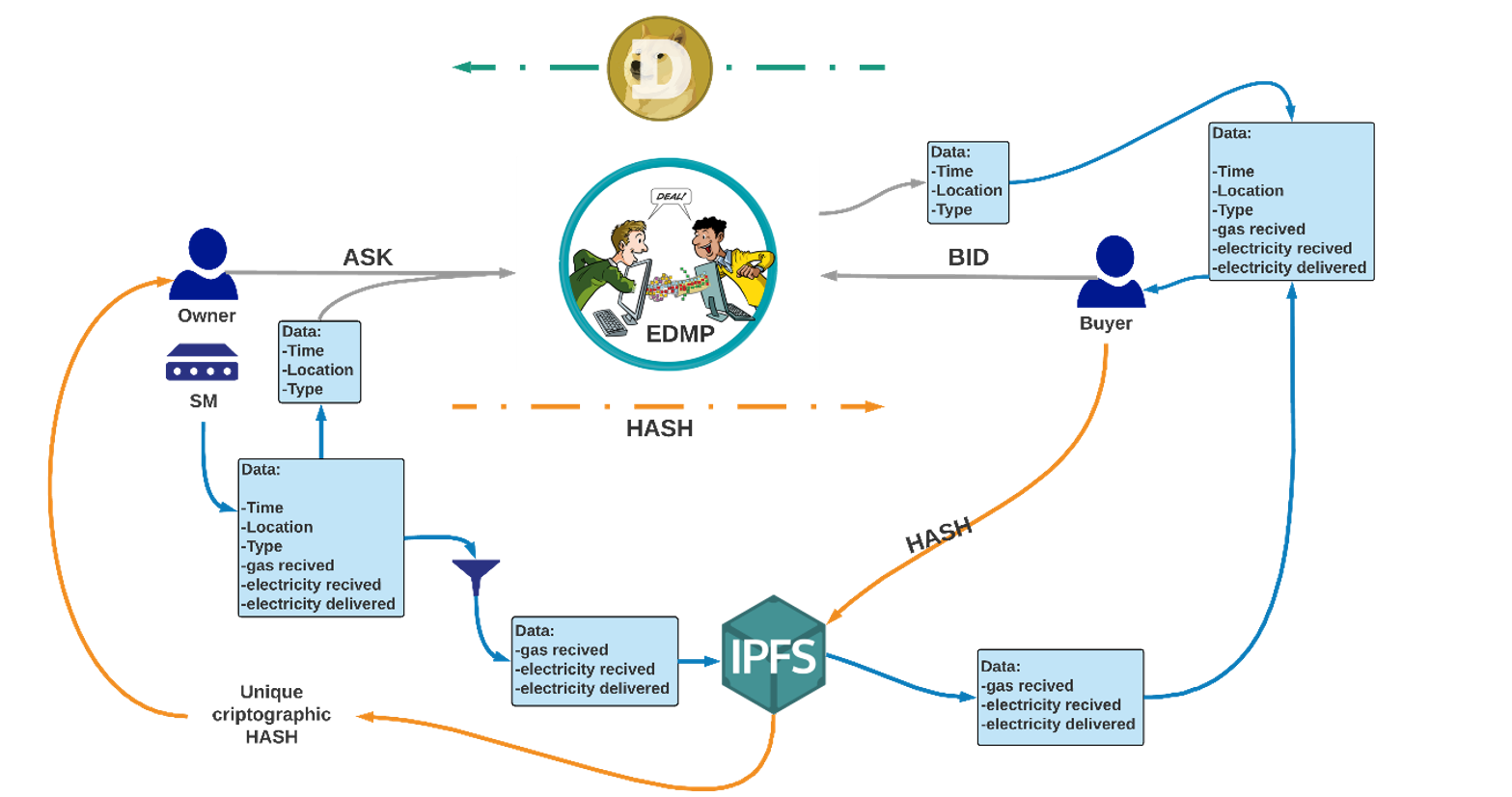

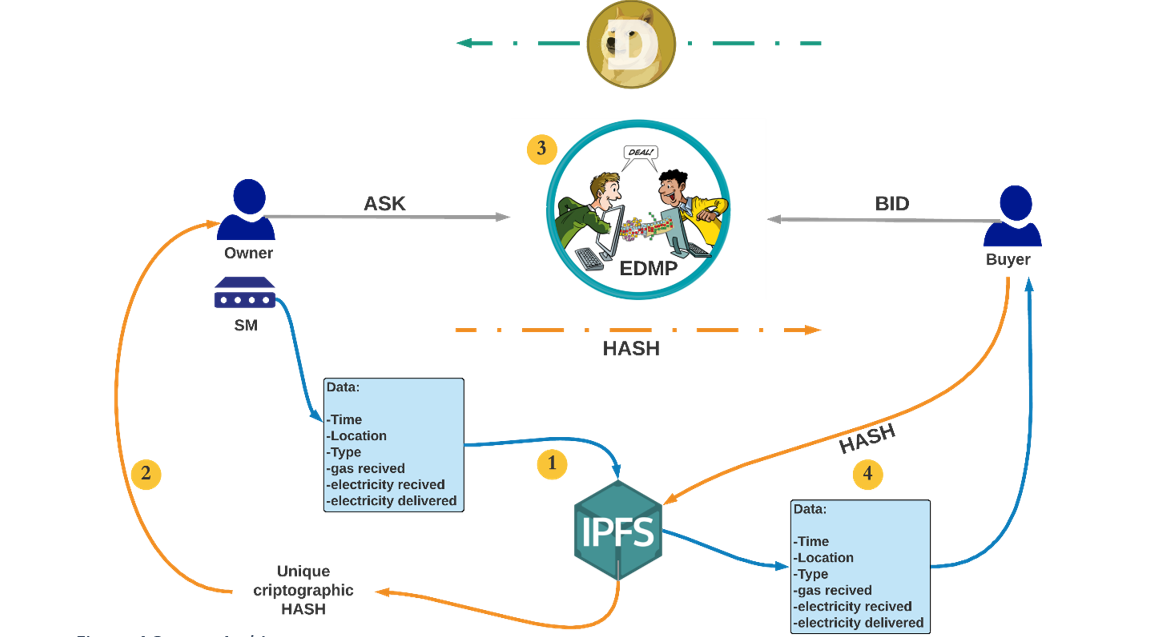

From a systemic point of view, the architecture of the overall process is the one depicted Figure 4. The overall process is made up of 4 steps all taking place inside the same server where the central market is coupled with a settlement provider represented by IPFS as a medium of data storage. The steps are the following:

-

The SM owner directly put the data generated inside IPFS, through the exploitation of an API. The choice was directed towards IPFS because it is designed to create a content-addressable, peer-to-peer method of storing data, allowing users to directly refer to data inside IPFS by using the hash generated by the data itself. Choosing to build a multi-party system was an obliged choice. In fact, blockchain does not efficiently transmit and store data, so in this architecture, a layer is entitled in transmit, store, and provide access to the data, i.e. IPFS, while the second layer, i.e. the DLT platform, is entitled in to track the availability of data, the provenance of the data, and to keep records of who is permitted to access the data.

-

The owner gets from IPFS the hash of the specific IPFS object where the consumption data are stored. In this way, we are sure of the unique correlation between the data and the IPFS object due to the direct bond between the data and their unique hash. Moreover, this allows a fast verification of tampering activity since a modification of data will result in a change in the hash. Finally, by using this mechanism, we add an additional layer of privacy since the item we are going to sell is not directly the data but their hash with no possibility of guessing the data from the hash. Is important to understand that now the commodity is represented by the hash itself since it will be what we are going to sell in the EnerDatX market.

-

The 3rd part is the central core procedure inside this design. As already said the blockchain has the task of recording the transaction between two users according to the particular architecture of TrustChain. The EDMP (Electricity Data Market Place) is where assets, represented by data, are sold by owner in exchange of token provided by buyers that will grant access to these specific data, as anticipated in point 1). We will further describe this part in the next chapter.

-

With hash ownership, certified by the recorded transaction in the blockchain, the buyer could finally purchase the data from IPFS by retrieving the IPFS object related to that hash. As mentioned before, by temporarily storing data, IPFS works as settlement provider for the assets traded, i.e. data, in the market, while the EDMP itself is also the settlement provider for currency transaction since Tokens are stored on the TrustChain Ledger (15).

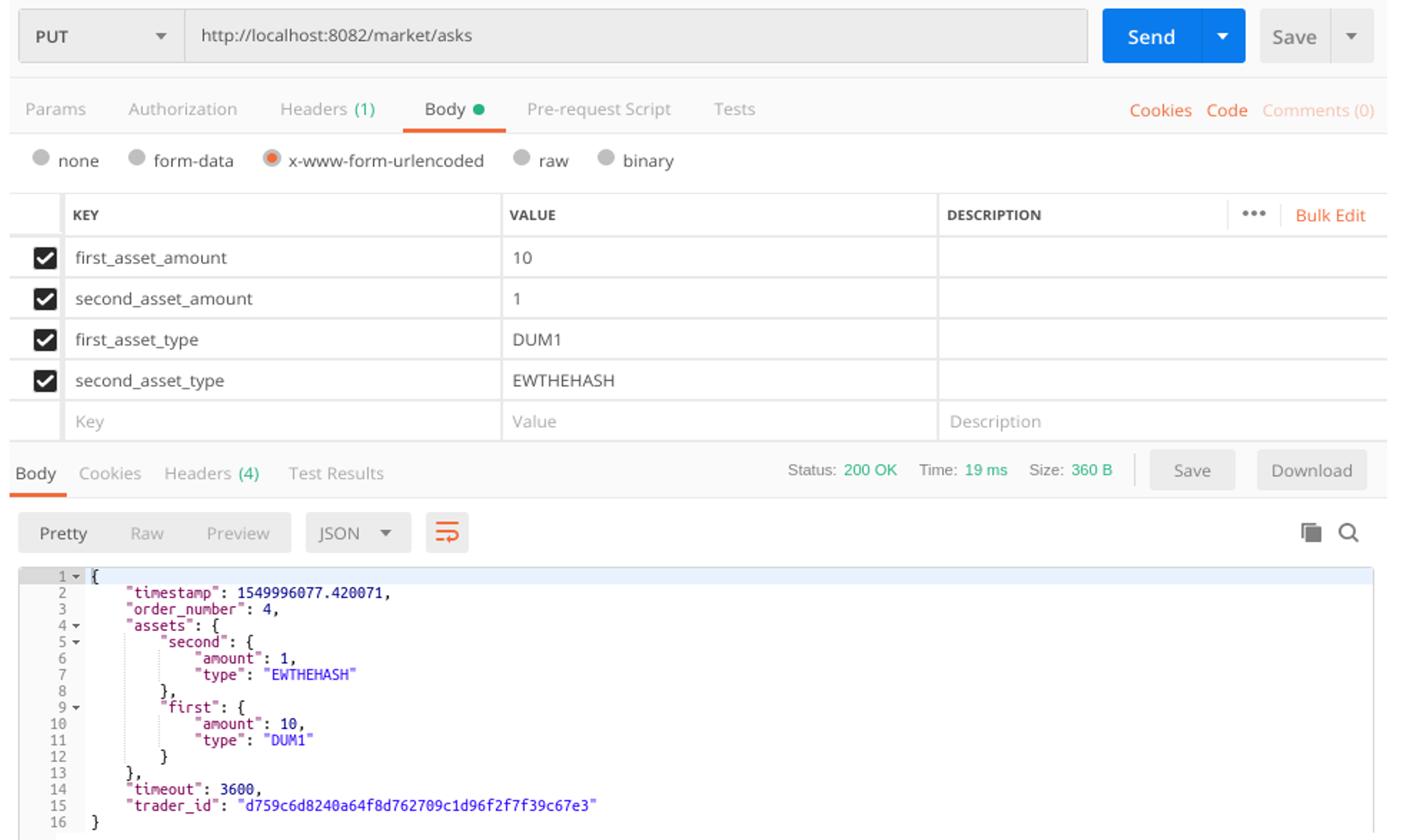

As we mentioned above, step 3 is the core of all the process and the central objective of our work since is the key blockchain component. For this reason, we will further discuss in detail its specific architecture. It is important to note that what follows will be related to a series of images which represents the processes taking place inside the market. One thing need to be mentioned is that in the following pictures, localhost:8082 is the owner while 8080 is the buyer.

- Ask order: First, once the hash is generated, the owner modifies the state of the market by sending an HTTP PUT request. This request is an ask order as represented by Figure 5. In this request, the owner indicates his willingness to selling a particular asset represented by the key:”second-asset-type”, i.e. the hash. This hash is preceded by a prefix, i.e. EW, in order to recognise that is an asset stored in the Electricity Wallet of the owner. The first-asset-type is instead the currency accepted for the transaction and above the amount of both asset for the transaction is indicated. In this case for the exchange of one hash 10 DUM1 are requested.

- Electricity wallet: In order to permit the identification of hash ownership, we modify the Tribler GitHub code by inserting a wallet able to store, in relation to owners’ public key, the hash owners create. This allows us to identify the property of a particular hash (and so of specific data related to it) and also to track the transferring of ownership from owner to buyer.

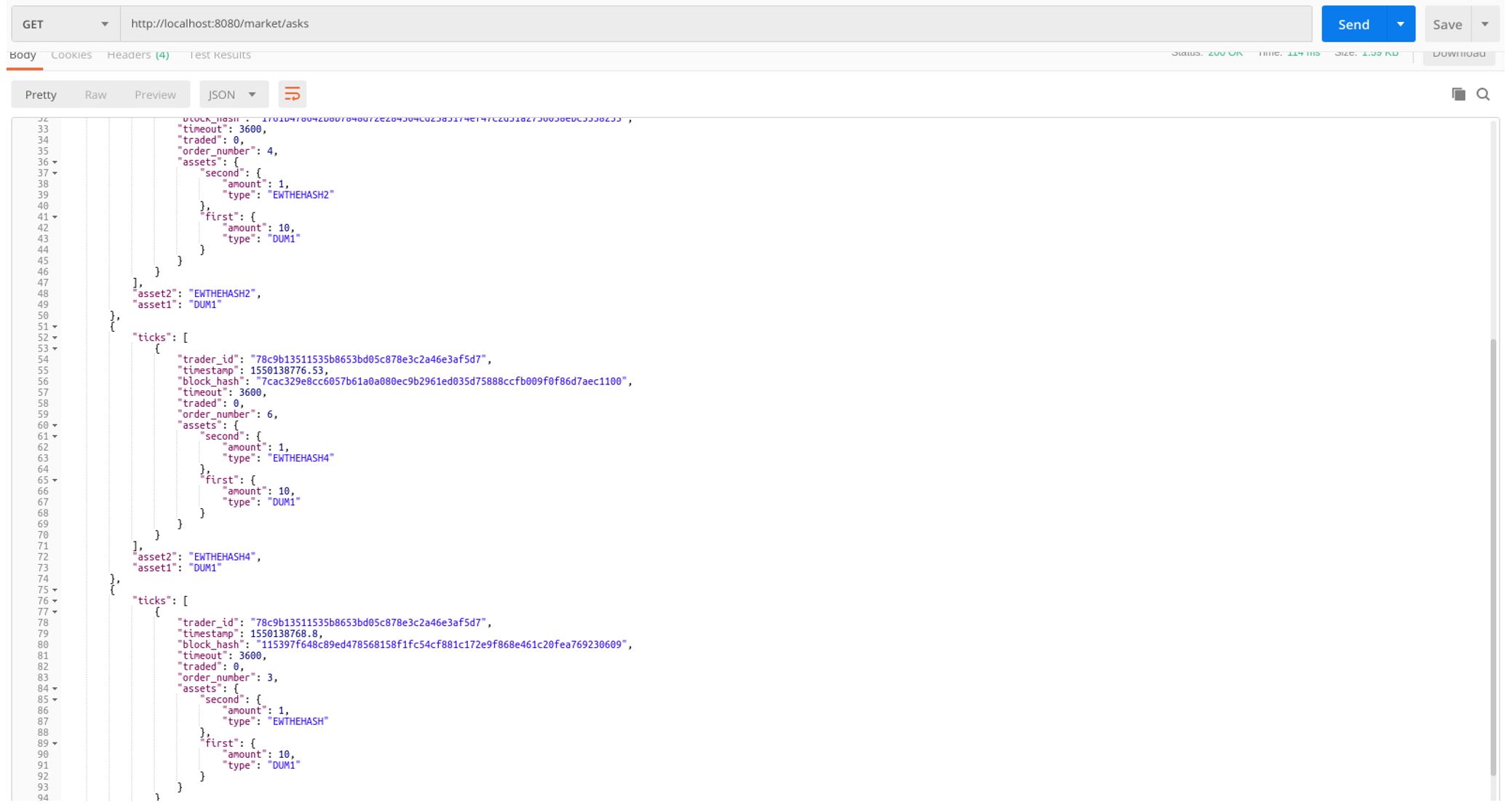

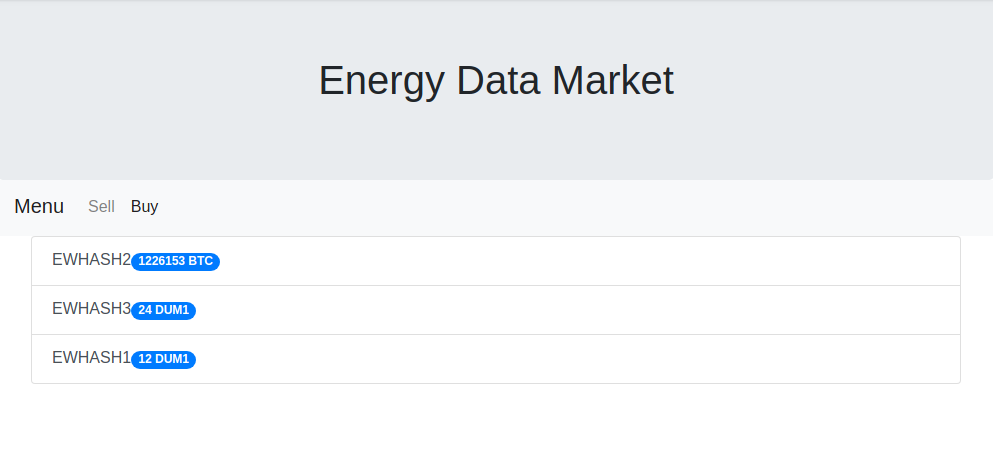

- Open orders fetching:

Once an ask order is present in the market, a buyer should be allowed to identify the particular assets available to buy. We allow buyers to see the currently available supply.

This operation is completed by sending an HTTP GET request to the market. The final result is the one represented in Figure 6 where a list of all available hash and the amount of DUM1 requested for each of them is present. As it is possible to see each request is related to a specific timestamp.

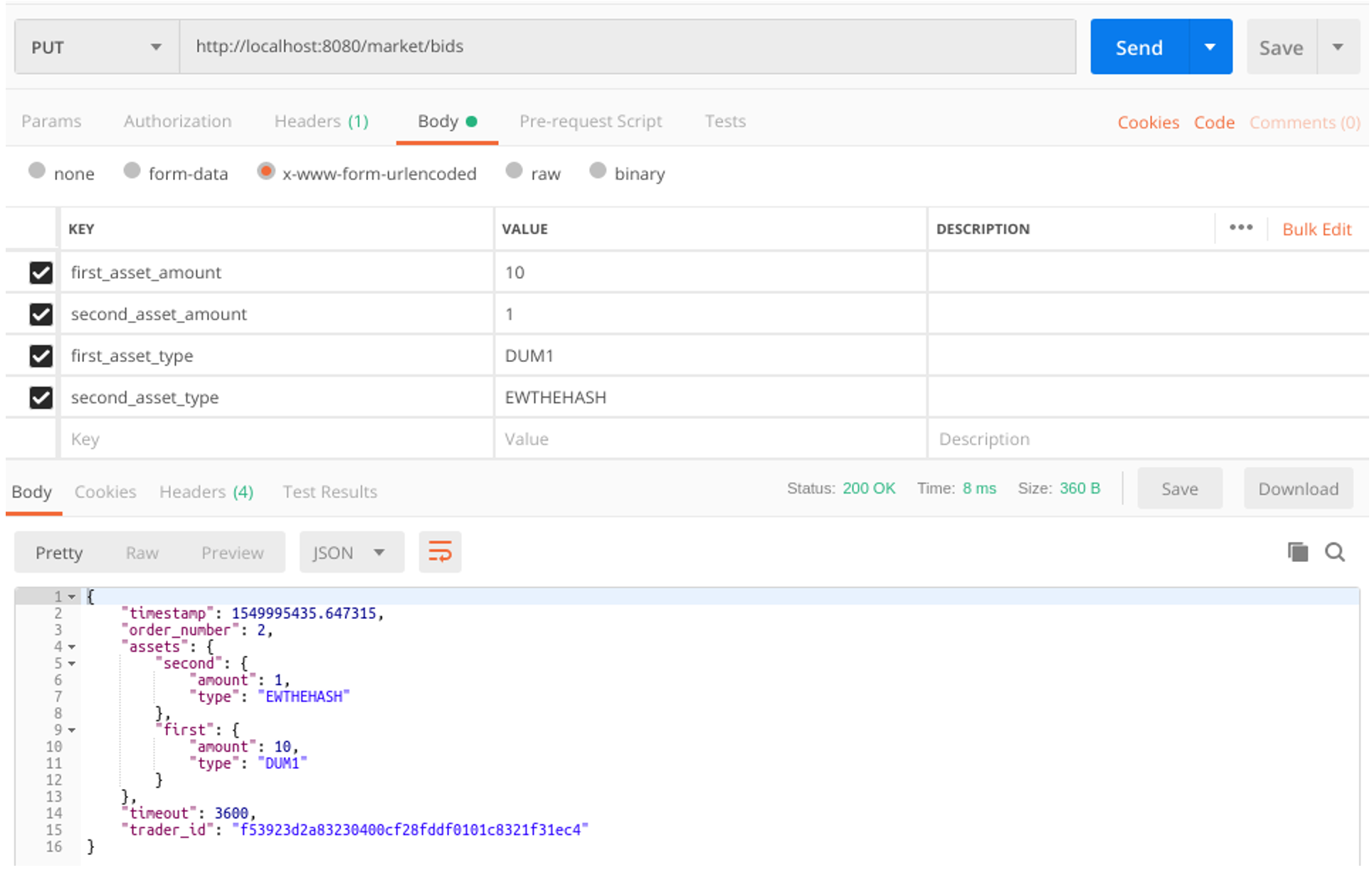

- Bid order:

Once identified the particular hash to buy, the buyer should make a bid order in order to be entitled to the ownership of that asset. As already explained EnerDatX works as a proof-of-ownership mechanism by recording transactions of assets and currency.

The buyer, as presented in Figure 7 create an HTTP PUT request, representing the bid. This request should refer to a hash present in the market, and it should match the amount of DUM1 requested. Basically, in this design, matching is performed by participants themselves in a way similar to Airbnb where users find their accommodations in an autonomous way (15). The matching engine will then automatically match the bid with the ask request since the buyer already performs matching. This mechanism could be ameliorated by enabling the possibility of offering a different amount for a specific hash and then guaranteeing a higher level of flexibility as described in (15).

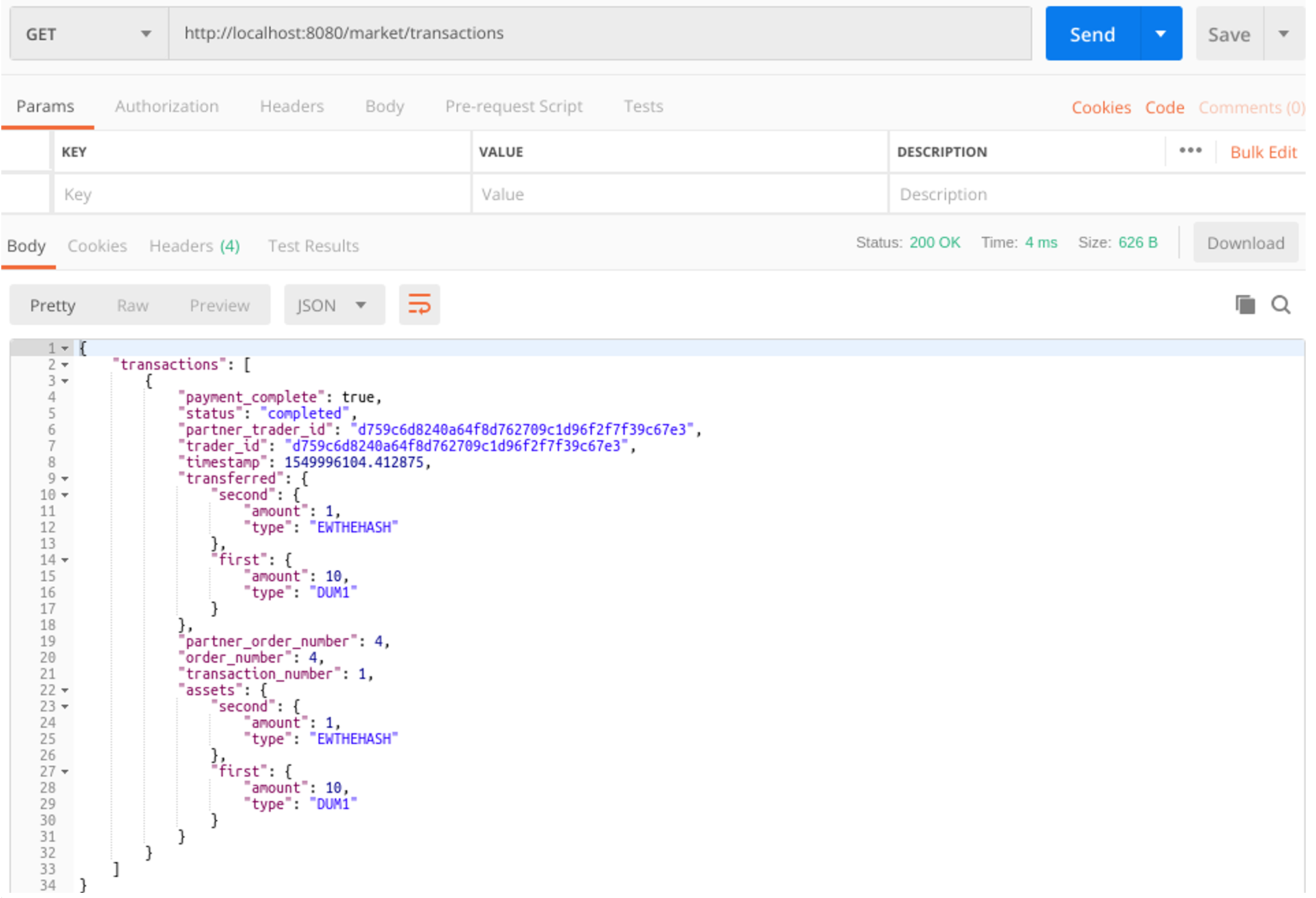

- Transaction finalisation:

After matching is performed, the transaction is validated and stored in the local chain of both transaction party, according to TrustChain mechanism. As it is possible to see in Figure 8 the transaction, if ask order request is satisfied, is eventually recorded. We can see that it lists what was transferred, the id of the counterparty and the buyer itself (in this case is the buyer watching the record) and the timestamp of the transaction record. Moreover, the amount of other orders created by the counterparty is present in the record, and the number of the specific transaction taken into account.

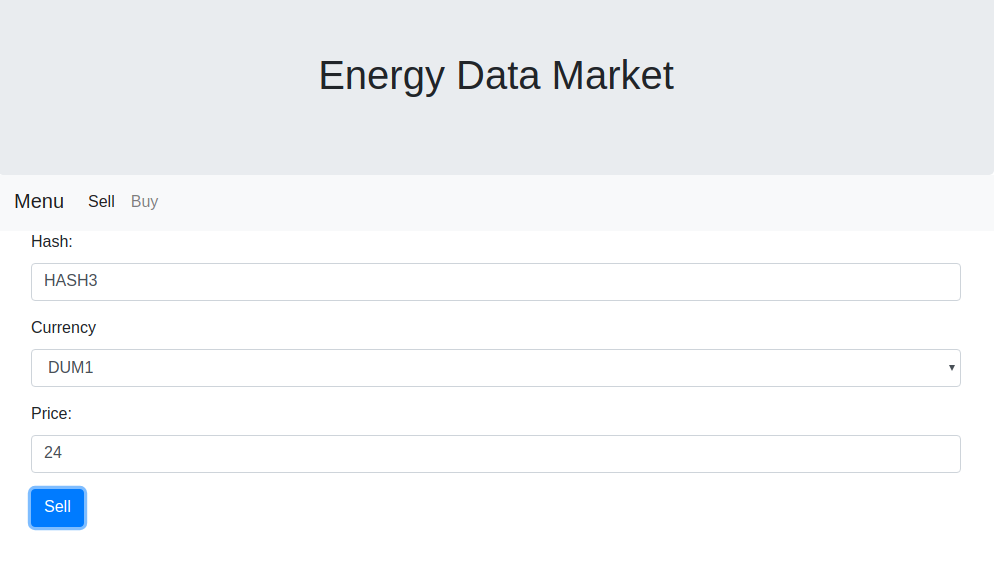

We created a small website that allows us to do the previous HTTP requests in a more user-friendly way for demo purposes. It allows the user to sell a hash, and to see all the hash in the market and create a bid for them.

As already mentioned, IPFS is used as a settlement provider to allow users to store and retrieve data coming from the SM.

IPFS primarily provide an ancillary service to our system securing the data transmission. However, the question is: how do we exploit it for our project?

First, the user, i.e. SM owner, connect its device trough OEHU API in order to retrieve data. He chooses his device by selecting his specific SM ID. The system will then get the data from the SM in a specific time, and it inserts it inside an IPFS object; thus a hash is generated as a pointer to that specific set of data.

Then the hash is copied and sold in the market as described above.

After proof-of-ownership determine the transaction of that data’s property by securely record the transaction in the distributed ledger, the buyer use IPFS in the reverse way. Using the hash provided he can go inside the specific IPFS object and retrieve the raw data provided by the OEHU API developed by BlockLab. We decided to use a raw data format as the one directly provided by the API since is a buyer interest and duty to process that data and add additional value over them, and is not task of the system to process and present differently that kind of data, since the system is designed to transfer data ownership and not to process data.

We present the IPFS steps exploiting the image provided below. Basically, the IPFS exploitation regards the initial and final part of the overall transaction process. From data recording to data retrieval.

.PNG)

During our project, we mainly work, as pointed out above, with two main elements: decentralised market and IPFS. The final part of the project was the integration in a unique component of: the uploading of data and selling of hash from the owner side and; from the buyer side the buying of the hash end the final download of the energy consumption data. We attempted an effort to integrate the Tribler & IPFS in a single GUI instead of the current version where we make market transactions and IPFS data upload/download through webpages. However, due to time limitations as creating a data market place on the Tribler is not feasible due to the complexity and extent of the code, we decided to go for the basic implementation using webpages. The attempt in the single integration resulted in the trying of creating an enhanced version of Tribler GUI with an additional feature of a separate Data marketplace to raise ask and accept a bid (data for currency) from a single interface. By the way, we start this attempt in order to understand its feasibility. An image of the resulted try is presented below. Further developments could result in a single interface of great integration between the different components.

We present above the design we implemented in order to create a system allowing users to trade energy consumption data. The design we build is primitive, since even if valid, it faces several problems that must be furtherly analysed and solved. In this section, a critical analysis is made to identify some of this point and to foster the development of solutions.

One big issue is that nothing stops a buyer to just simply copy a hash present in the available supply (see Figure 6) and directly goes in the IPFS and taking the data related to that hash freely. Of course, the transaction will be not stored in the EDMP, this certifying the ownership of that specific set of data, but a malicious user could be only interested in using this data for personal use without worrying of proof-of-ownership.

A solution could be data branching, i.e. dividing the data as depicted in Figure 11. Then put only electricity consumption data in the IPFS while using time and location as an asset description in the market. Only after the transaction is completed, the owner provides to the buyer the hash related to the consumption data inside the IPFS. It is essential to understand that solely consumption data divided by time and location lose their meaning and for this reason, all the three assets (consumption data, descriptive data, hash) are necessary for the full completion of the exchange. This solution will also solve the problem of selling just a hash that does not give any information about the fundamental characteristics of the data related to it. Basically time, type and location will work as data description.

For the reason above introduced, in our work, we supposed a network of trusted individuals, where buyers already know at which data each hash is referred.

Here we attach the OEHU API from where the energy consumption data where retrived.

Note that electricity is in kWh and gas in m3

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2018. France : IEA Publications, 2018.

- —. Digitalization & Energy. France : IEA PUBLICATIONS, 2017.

- Blockchain technology in the energy sector: A systematic review of challenges and opportunities. Andoni, Merlinda, et al. 2019, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, pp. 143–174.

- Designing microgrid energy markets A case study: The Brooklyn Microgrid. Mengelkamp, Esther, et al. 2018, Applied Energy, pp. 870–880.

- Power Ledger. Power Ledger: Energy, reimagined. [Online] Power Ledger, 2018. [Cited: 2 Febbruary 2019.] https://www.powerledger.io/.

- BlockLab. BLOCKCHAIN X ENERGY, A NATURAL MATCH. Rotterdam : BlockLab, 2017.

- The Economist. The world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data. The Economist. 6 May 2016.

- Evans, Richard and Gao, Jim. DeepMind AI Reduces Google Data Centre Cooling Bill by 40%. [Online] DeepMind, 20 July 2016. [Cited: 2 Febbruary 2019.] https://deepmind.com/blog/deepmind-ai-reduces-google-data-centre-cooling-bill-40/.

- Beam, Andrew L. You can probably use deep learning even if your data isn't that big. [Online] GitHub, 4 Jun 2017. [Cited: 4 Febbruary 2019.] https://beamandrew.github.io/deeplearning/2017/06/04/deep_learning_works.html.

- Moylan, John. Smart meter IT system delayed until autumn. BBC News. 17 August 2016.

- House of Common. Smart meters: progress or delay? London : House of Commons, 2015.

- Grimwood, Tom. Ofgem penalises DCC for missing go-live deadlines. Utility Week. 22 February 2018.

- —. DCC exceeds annual cost forecast by £68 million . Utility Week. 27 October 2017.

- TrustChain: A Sybil-resistant scalable blockchain. Otte, Pim, de Vos, Martijn and Pouwelse, Johan. Article in Press, Future Generation Computer Systems.

- XChange: A Generic Blockchain Mechanism for Trading at Scale. de Vos, Martijn and Pouwelse, Johan. s.l. : Not yet pubblished, 2018.

- BlockLab. Open Energy Hub for smart meter data. OHEU. [Online] BlockLab. [Cited: 2 Febbruary 2019.] https://oehu.org/.

- Waldman, Jonathan. Blockchain Fundamentals. s.l. : Microsoft Corportaion, 2018.

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)