PRVHASH - Pseudo-Random-Value Hash

Introduction

PRVHASH is a hash function that generates a uniform pseudo-random number

sequence

derived from the message. PRVHASH is conceptually similar (in the sense of

using a pseudo-random number sequence as a hash) to keccak

and RadioGatun

schemes, but is a completely different implementation of such concept.

PRVHASH is both a "randomness extractor"

and an "extendable-output function" (XOF).

PRVHASH can generate 64- to unlimited-bit hashes, yielding hashes of approximately equal quality independent of the chosen hash length. PRVHASH is based on 64-bit math. The use of the function beyond 1024-bit hashes is easily possible, but has to be statistically tested. For example, any 32-bit element extracted from 2048-, or 4096-bit resulting hash is as collision resistant as just a 32-bit hash. It is a fixed execution time hash function that depends only on message's length. A streamed hashing implementation is available.

PRVHASH is solely based on the butterfly effect, inspired by LCG

pseudo-random number generators. The generated hashes have good avalanche

properties. For best security, a random seed should be supplied to the hash

function, but this is not a requirement. In practice, the InitVec (instead

of UseSeed), and initial hash, can both be randomly seeded (see the

suggestions in prvhash64.h), adding useful initial entropy (InitVec plus

Hash total bits of entropy).

64-, 128-, 192-, 256-, 512-, and 1024-bit PRVHASH hashes pass all SMHasher tests. Other hash lengths were not thoroughly tested, but extrapolations can be made. The author makes no cryptographic claims (neither positive nor negative) about PRVHASH-based constructs.

PRVHASH core hash function can be used as a PRNG with an arbitrarily-chosen (practically unlimited) period, depending on the number of hashwords in the system.

Please see the prvhash64.h file for the details of the basic hash function

implementation (the prvhash.h, prvhash4.h, prvhash42.h are outdated

versions). While this hash function is most likely irreversible, according to

SAT solver-based testing, it does not feature a preimage resistance. This

function should not be used in open systems, without a secret seed. Note that

64 refers to core hash function's variable size.

The default prvhash64.h-based 64-bit hash of the string The cat is out of the bag is eb405f05cfc4ae1c.

A proposed short name for hashes created with prvhash64.h is PRH64-N,

where N is the hash length in bits (e.g. PRH64-256).

Minimal PRNG for Everyday Use

The core hash function can be easily integrated into your applications, to be

used as an effective PRNG. The period of this minimal PRNG is at least

2159. The initial parameters can be varied at will, and won't

"break" the PRNG. Setting only the Seed value guarantees a random start

point within the whole PRNG period, with at least 264 spacing.

The code follows.

#include "prvhash_core.h"

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

uint64_t Seed = 0;

uint64_t lcg = 0;

uint64_t Hash = 0;

uint64_t v = 0;

uint64_t i;

for( i = 0; i < ( 1ULL << 28 ); i++ )

{

v = prvhash_core64( &Seed, &lcg, &Hash );

}

printf( "%llu\n", v );

}

Note that such minimal 1-hashword PRNG is most definitely not cryptographically-secure: its state can be solved by a SAT solver pretty fast; this applies to other arrangements ("parallel", "fused", multiple hashwords; with daisy-chaining being harder to solve). The known way to make PRNG considerably harder to solve for a SAT solver, with complexity corresponding to system's size, is to combine two adjacent PRNG outputs via XOR operation; this obviously has a speed impact and produces output with more than 1 solution (most probably, 2). This, however, does not measurably increase the probability of PRNG output overlap, which stays below 1/2sys_size_bits; in tests, practically undetectable.

So, the basic PRNG with some, currently not formally-proven, security is as follows (XOR two adjacent outputs to produce a single "compressed" PRNG output):

v = prvhash_core64( &Seed, &lcg, &Hash );

v ^= prvhash_core64( &Seed, &lcg, &Hash );

A similar approach is to simply skip the next generated random number, but it is slightly less secure. It is likely that PRVHASH's k-equidistribution of separate outputs is implicitly secure.

TPDF Dithering

The core hash function can be used to implement a "statistically-good" and "neutrally-sounding" dithering noise for audio signals; for both floating-point to fixed-point, and bit-depth conversions.

uint64_t rv = prvhash_core64( &Seed, &lcg, &Hash );

double tpdf = ( (int64_t) (uint32_t) rv - (int64_t) ( rv >> 32 )) * 0x1p-32;

Floating-Point PRNG

The following expression can be used to convert 64-bit unsigned value to full-mantissa floating-point value, without a truncation bias:

uint64_t rv = prvhash_core64( &Seed, &lcg, &Hash );

double v = ( rv >> ( 64 - 53 )) * 0x1p-53;

Gradilac PRNG (C++)

The gradilac.h file includes the Gradilac C++ class which is a generalized

templated implementation of PRVHASH PRNG that provides integer, single bit,

floating-point, TPDF, Normal random number generation with a straight-forward

front-end to specify PRVHASH system's properties. Supports on-the-go

re-seeding, including re-seeding using sparse entropy (for CSPRNG uses). Does

not require other PRVHASH header files.

Use Gradilac< 316 > to match Mersenne Twister's PRNG period.

Note that this class may not be as efficient for "bulk" random number generation as a custom-written code. Nevertheless, Gradilac PRNG class, with its 1.0 cycles/byte floating-point performance (at default template settings), is competitive among other C++ PRNGs.

PRVHASH64_64M

This is a minimized implementation of the prvhash64 hash function. Arguably,

it's the smallest hash function in the world, that produces 64-bit hashes of

this quality level. While this function does not provide a throughput that can

be considered "fast", due to its statistical properties it is practically fast

for hash-maps and hash-tables.

Entropy PRNG

PRVHASH can be also used as an efficient general-purpose PRNG with an external

entropy source injections (like how the /dev/urandom works on Unix): this

was tested, and works well when 8-bit true entropy injections are done

inbetween 8 to 2048 generated random bytes (delay is also obtained via the

entropy source). An example generator is implemented in the prvrng.h file:

simply call the prvrng_test64p2() function.

prvrng_gen64p2()-based generator passes PractRand

32 TB threshold with rare non-systematic "unusual" evaluations. Which suggests

it's the working randomness extractor that can "recycle" entropy of any

statistical quality, probably the first in the world.

Note that due to the structure of the core hash function the probability of PRNG completely "stopping", or "stalling", or losing internal entropy, is absent.

The core hash function, without external entropy injections, with any initial

combination of lcg, Seed, and Hash eventually converges into one of

random number sub-sequences. These are mostly time-delayed versions of only a

smaller set of unique sequences. There are structural limits in this PRNG

system which can be reached if there is only a small number of hashwords in

the system. PRNG will continously produce non-repeating random sequences given

external entropy input, but their statistical quality on a larger frames will

be limited by the size of lcg and Seed variables, and the number of

hashwords in the system, and the combinatorial capacity of the external

entropy. A way to increase the structural limit is to use the "parallel" PRNG

arrangement demonstrated in the prvhash64s.h file, which additionally

increases the security exponentially. Also any non-constant entropy input

usually increases the period of randomness, which, when extrapolated to

hashing, means that the period increases by message's combinatorial capacity

(or the number of various combinations of its bits). The maximal PRNG period's

2N exponent is hard to approximate exactly, but in most tests it

was equal to at least system's size in bits, minus the number of hashwords in

the system, minus 1/4 of lcg and Seed variables' size (e.g., 159 for a

minimal PRNG).

Moreover, the PRVHASH systems can be freely daisy-chained by feeding their

outputs to Seed/lcg inputs, adding some security firewalls, and increasing

the PRNG period of the final output accordingly. Note that any external PRNG

output can be inputted via either Seed, lcg, or both, yielding PRNG period

exponent summation. For hashing and external unstructured entropy, only

simultaneous input via Seed and lcg works in practice (period's exponent

increase occurs as well).

While lcg, Seed, and Hash variables are best initialized with good

entropy source (however, structurally, they can accept just about any entropy

quality while only requiring an initial "conditioning"), the message can be

sparsely-random: even an increasing counter can be considered as having a

suitable sparse entropy.

Two-Bit PRNG

This is a "just for fun" example, but it passes 256 MB PractRand threshold. You CAN generate pseudo-random numbers by using 2-bit shuffles; moreover, you can input external entropy into the system.

#include <stdio.h>

#include "prvhash_core.h"

#define PH_HASH_COUNT 42

int main()

{

uint8_t Seed = 0;

uint8_t lcg = 0;

uint8_t Hash[ PH_HASH_COUNT ] = { 0 };

int HashPos = 0;

int l;

for( l = 0; l < 256; l++ )

{

uint8_t r = 0;

int k;

for( k = 0; k < 4; k++ )

{

r <<= 2;

r |= prvhash_core2( &Seed, &lcg, Hash + HashPos );

HashPos++;

if( HashPos == PH_HASH_COUNT )

{

HashPos = 0;

}

}

if( l > PH_HASH_COUNT / 3 ) // Skip PRNG initialization.

{

printf( "%4i ", (int) r );

}

}

}

Streamed Hashing

The file prvhash64s.h includes a relatively fast streamed hashing function

which utilizes a "parallel" PRVHASH arrangement. Please take a look at the

prvhash64s_oneshot() function for usage example. The prvhash64s offers

an increased security and hashing speed.

This function has an increased preimage resistance compared to the basic hash function implementation. Preimage resistance cannot be currently estimated exactly, but the hash length affects it exponentially. Also, preimage attack usually boils down to exchange of forged symbols to "trash" symbols (at any place of the data stream); substitutions usually end up as being quite random, possibly damaging to any compressed or otherwise structured file. Which means that data compression software and libraries should always check any left-over, "unused", data beyond the valid compressed stream, for security reasons.

Time complexity for preimage attack fluctuates greatly as preimage resistance likely has a random-logarithmic PDF of timing.

Even though a formal proof is not yet available, the author assumes this hash function can compete with widely-used SHA2 and SHA3 families of hash functions while at the same time offering a considerably higher performance and scalability. When working in open systems, supplying a secret seed is not a requirement for this hash function.

The performance (expressed in cycles/byte) of this hash function on various platforms can be evaluated at the ECRYPT/eBASH project.

The default prvhash64s.h-based 64-bit hash of the string The cat is out of the bag is 2043ccf52ae2ca6f.

The default prvhash64s.h-based 256-bit hash of the string

Only a toilet bowl does not leak is

b13683799b840002689a1a42d93c826c25cc2d1f1bc1e48dcd005aa566a47ad8.

The default prvhash64s.h-based 256-bit hash of the string

Only a toilet bowl does not leaj is

d4534a922fd4f15ae8c6cc637006d1f33f655b06d60007a226d350e87e866250.

This demonstrates the Avalanche effect. On a set of 216553 English words, pair-wise hash comparisons give average 50.0% difference in resulting hash bits, which fully satisfies the strict avalanche criterion.

This streamed hash function produces hash values that are different to the

prvhash64 hash function. It is incorrect to use both of these hash function

implementations on the same data set. While prvhash64 can be used as a hash

for hash-tables and in-memory data blocks, prvhash64s can be used to create

hashes of large data blocks like files, in streamed mode.

A proposed short name for hashes created with prvhash64s.h is PRH64S-N,

where N is the hash length in bits (e.g. PRH64S-256). Or simply, SH4-N,

Secure Hash 4.

Description

Here is the author's vision on how the core hash function works. In actuality, coming up with this solution was accompanied by a lot of trial and error. It was especially hard to find a better "hashing finalization" solution.

Seed ^= msgw; lcg ^= msgw; // Mix in external entropy (or daisy-chain).

Seed *= lcg * 2 + 1; // Multiply random by random, without multiply by zero.

const uint64_t rs = Seed >> 32 | Seed << 32; // Produce halves-swapped copy.

Hash += rs + 0xAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA; // Accumulate to hash, add raw entropy (self-start).

lcg += Seed + 0x5555555555555555; // Output-bound entropy accumulation, add raw entropy.

Seed ^= Hash; // Mix new seed value with hash. Entropy feedback.

const uint64_t out = lcg ^ rs; // Produce "compressed" output.

This function can be arbitrarily scaled to any even-sized variables: 2-, 4-,

8-, 16-, 32-, 64-bit variable sizes were tested, with similar statistical

results. Since mathematical structure of the function does not depend on the

variables' size, statistical analysis can be performed using smaller variable

sizes, with the results being extrapolatable to larger variable sizes, with a

high probability (the function is invariant to the variable size). Also note

that the 0xAAAA... constant is not an arbitrary constant since it should be

produced algorithmically by replicating the 10 bit-pairs, to match the

variable size; it represents the "raw entropy bit-train". The same applies to

the 0x5555... constant. An essential property of these bit-trains is that

they are uncorrelated to any uniformly-random bit-sequences, at all times.

Practically, 10 and 01 bit-pairs can be also used as constants, without

replication, but this does not provide conclusively better results for PRNG,

and does not work well for hashing; also, self-starting period becomes

longer. A conceptual aspect of replicated bit-pairs is that they represent the

simplest maximum-entropy number (bit-pair is a minimal sequence that can

exhibit entropy, with replication count bound to the state variable size).

While "magic numbers" can be used instead of these bit-trains (at least for

PRNG), they do not posses the property of being simplest.

It's important to point out that the presence of the 0xAAAA... and

0x5555... constants logically assure that the Seed and lcg variables

quickly recover from the "zero-state". Beside that, these constants logically

prohibit synchronous control over Seed and lcg variables: different bits

of the input entropy will reach these variables. When the system starts from

the "zero-state", with many hashwords in the system, it is practically

impossible to find a preimage (including a repetitious one) that stalls the

system, and thus it is impossible to perform a multi-collision attack.

However, since this risk cannot be estimated exactly, the prvhash64s hash

function adds a message length value to the end of the data stream.

How does it work? First of all, this PRNG system, represented by the core hash

function, does not work with numbers in a common sense: it works with

entropy,

or random sequences of bits. The current "expression" of system's overall

internal entropy - the Seed - gets multiplied ("smeared") by a supporting,

output-bound variable - lcg, - which is also a random value, transformed in

an LCG-alike manner. As a result, a new random value is produced which

represents two independent random variables (in lower and higher parts of the

register), a sort of "entropy stream sub-division" happens. This result is

then halves-swapped, and is accumulated in the Hash together with the 10

bit-train which adds the "raw entropy", allowing the system to be

self-starting. The original multiplication result is accumulated in the lcg

variable. The Seed is then updated with the hashword produced on previous

rounds. The reason the message's entropy (which may be sparse or non-random)

does not destabilize the system is because the message becomes hidden in the

internal entropy (alike to a cryptographic one-time-pad); message's

distribution becomes unimportant, and system's state remains statistically

continuous. Both accumulations - of the halves-swapped and the original

result of multiplication - produce a uniformly-distributed value in the

corresponding variables; a sort of "de-sub-division" happens in these.

The two instructions - Seed *= lcg * 2 + 1, lcg += Seed - represent an

"ideal" bit-shuffler: this construct represents a "bivariable shuffler" which

transforms the input lcg and Seed variables into another pair of variables

with 50% bit difference relative to input, and without collisions. The whole

core hash function, however, uses a more complex mixing which produces a hash

value: the pair composed of the hash value and either a new lcg or a new

Seed value also produces no input-to-output collisions. Thus it can be said

that the system does not lose any input entropy. In 4-dimensional analysis,

when Seed, lcg, Hash, and msgw values are scanned and transformed into

subsequent Seed, lcg, and Hash triplets, this system does not exhibit

local state change-related collisions due to external entropy input (all

possible input msgw values map to subsequent triplets uniquely). However,

with a small variable size (8-bit) and a large output hash size, a sparse

entropy input has some probability of "re-sychronization" event happening,

leading to local collisions. With 16-bit variables, or even 8-bit parallel-2

arrangement (with the local state having 40-bit size instead of 24-bit),

probability of such event is negligible. While non-parallel hashing may even

start from the "zero-state", for reliable hashing the state after 5

"conditioning" rounds should be used.

Another important aspect of this system, especially from the cryptography

standpoint, is the entropy input to output latency. The base latency for

state-to-state transition is equal to 1 (2 for "parallel" arrangements); and

at the same time, 1 in hash-to-hash direction: this means that PRVHASH

additionally requires a full pass through the hashword array, for the entropy

to propagate, before using its output. However, hashing also requires a pass

to the end of the hashword array if message's length is shorter than the

output hash, to "mix in" the initial hash value. When there is only 1 hashword

in use, there is no hashword array-related delay, and thus the entropy

propagation is only subject to the base latency. The essence of these

"latencies" is that additional rounds are needed for the system to get rid of

a statistical traces of the input entropy. Note that the "parallel"

arrangement increases shuffling quality. However, this increase is relative to

the state variable size: for example, 8-bit parallel-2 arrangement with 8-bit

input is equivalent to 16-bit non-parallel arrangement with 16-bit input. So,

it is possible to perform hashing with 8-bit state variables if parallel-2

round is done per 1 input byte. The way "parallel" structure works is

equivalent to shuffling all entropy inputs in a round together (input 1 is

shuffled into a hash value which is then shuffled with input 2 into a hash

value, etc). The "parallel" arrangement may raise a question whether or not

it provides a target collision resistance as it seemingly "compresses" several

inputs into a single local hashword: without doubt it does provide target

collision resistance since Seed and lcg variables are a part of the

system, and their presence in the "parallel" arrangement increases the overall

PRNG period of the system and thus its combinatorial capacity.

Without external entropy (message) injections, the function can run for a

prolonged time, generating pseudo-entropy, in extendable-output PRNG mode.

When the external entropy (message) is introduced, the function "shifts" into

an unrelated state unpredictably. So, it can be said that the function "jumps"

within a space of a huge number of pseudo-random sub-sequences. Hash

length affects the size of this "space of sub-sequences", permitting the

function to produce quality hashes for any required hash length.

Statistically, these "jumps" are close to uniformly-random repositioning: each

simultaneous augmentation of Seed and lcg corresponds to a new random

position, with a spread over the whole PRNG period. The actual performace is

more complicated as this PRNG system is able to converge into unrelated random

number sequences of varying lengths, so the "jump" changes both the position

and the "index" of sub-sequence. This property of PRVHASH assures that

different initial states of its Seed state variable (or lcg, which is

mostly equivalent at initialization stage) produce practically unrelated

random number sequences, permitting to use PRVHASH for PRNG-based simulations.

In essence, the hash function generates a continuous pseudo-random number

sequence, and returns the final part of the sequence as a result. The message

acts as a "pathway" to this final part. So, the random sequence of numbers can

be "programmed" to produce a necessary outcome. However, as this PRNG does

not expose its momentary internal state, such "programming" is hardly possible

to perform for an attacker, even if the entropy input channel is exposed:

consider the (A^C)*(B^C) equation; an adversary can control C, but does

not know the values of A and B; thus this adversary cannot predict the

outcome. Beside that, as the core hash function naturally eliminates the bias

from the external entropy of any statistical quality and frequency, its

control may be fruitless. Note that to reduce such "control risks", the

entropy input should use as fewer bits as possible, like demonstrated in the

prvrng.h file.

P.S. The reason the InitVec in the prvhash64 hash function has the value

quality constraints, and an initial non-zero state, is that otherwise the

function would require 5 preliminary "conditioning" rounds (core hash function

calls) to neutralize any oddities (including zero values) in InitVec; that

would reduce the performance of the hash function dramatically, for hash-table

uses. Note that the prvhash64s function starts from the "full zero" state

and then performs acceptably.

Hashing Method's Philosophy

Any external entropy (message) that enters this PRNG system acts as a high-frequency and high-quality re-seeding which changes the random number generator's "position" within the PRNG period, randomly. In practice, this means that two messages that are different in even 1 bit, at any place, produce "final" random number sequences, and thus hashes, that are completely unrelated to each other. This also means that any smaller part of the resulting hash can be used as a complete hash. Since the hash length affects the PRNG period (and thus the combinatorial capacity) of the system, the same logic applies to hashes of any length while meeting collision resistance specifications for all lengths.

Alternatively, the hashing method can be viewed from the standpoint of classic bit-mixers/shufflers: the hashword array can be seen as a "working buffer" whose state is passed back into the "bivariable shuffler" continuously, and the new shuffled values stored in this working buffer for the next pass.

PRNG Period Assessment

The following "minimal" implementation of PractRand class can be used to

independently assess randomness period properties of PRVHASH. By varying

the PH_HASH_COUNT and PH_PAR_COUNT values it is possible to test various

PRNG system sizes. By adjusting other values it is possible to test PRVHASH

scalability across different state variable sizes (PractRand class and PRNG

output size should be matched, as PractRand test results depend on PRNG output

size). PractRand should be run with the -tlmin 64KB parameter, to evaluate

changes to the constants quicker. Note that both PH_HASH_COUNT and

PH_PAR_COUNT affect the PRNG period exponent not exactly linearly for small

variable sizes: there is a saturation factor present for small variable sizes;

after some point the period increase is non-linear due to small shuffling

space. Shuffling space can be increased considerably with a "parallel"

arrangement. Depending on the initial seed value, the period may fluctuate.

The commented out Ctr++... instructions can be uncommented to check the

period increase due to sparse entropy input. You may also notice the ^=h

instructions: PRVHASH supports feedback onto itself (it's like hashing its own

output). This operation, which can be applied to any parallel element,

maximizes the achieved PRNG period.

#include "prvhash_core.h"

#include <string.h>

#define PH_PAR_COUNT 1 // PRVHASH parallelism.

#define PH_HASH_COUNT 4 // Hashword count (any positive number).

#define PH_STATE_TYPE uint8_t // State variable's physical type.

#define PH_FN prvhash_core4 // Core hash function name.

#define PH_BITS 4 // State variable's size in bits.

#define PH_RAW_BITS 8 // Raw output bits.

#define PH_RAW_ROUNDS ( PH_RAW_BITS / PH_BITS ) // Rounds per raw output.

class DummyRNG : public PractRand::RNGs::vRNG8 {

public:

PH_STATE_TYPE Seed[ PH_PAR_COUNT ];

PH_STATE_TYPE lcg[ PH_PAR_COUNT ];

PH_STATE_TYPE Hash[ PH_HASH_COUNT ];

int HashPos;

DummyRNG() {

memset( Seed, 0, sizeof( Seed ));

memset( lcg, 0, sizeof( lcg ));

memset( Hash, 0, sizeof( Hash ));

HashPos = 0;

// Initialize.

int k, j;

for( k = 0; k < PRVHASH_INIT_COUNT; k++ )

{

for( j = 0; j < PH_PAR_COUNT; j++ )

{

PH_FN( Seed + j, lcg + j, Hash + HashPos );

}

}

}

Uint8 raw8() {

uint64_t OutValue = 0;

int k, j;

for( k = 0; k < PH_RAW_ROUNDS; k++ )

{

// Ctr++;

// Seed[ 0 ] ^= ( Ctr ^ ( Ctr >> 4 )) & 15;

// lcg[ 0 ] ^= ( Ctr ^ ( Ctr >> 4 )) & 15;

uint64_t h = 0;

for( j = 0; j < PH_PAR_COUNT; j++ )

{

h = PH_FN( Seed + j, lcg + j, Hash + HashPos );

}

// Seed[ 0 ] ^= h;

// lcg[ 0 ] ^= h;

if( PH_BITS < sizeof( uint64_t )) OutValue <<= PH_BITS;

OutValue |= h;

if( ++HashPos == PH_HASH_COUNT )

{

HashPos = 0;

}

}

return( OutValue );

}

void walk_state(PractRand::StateWalkingObject *walker) {}

void seed(Uint64 sv) { Seed[ 0 ] ^= sv; }

std::string get_name() const { return "PRVHASH"; }

};

PRVHASH Cryptanalysis Basics

When the system state is not known, when PRVHASH acts as a black-box, one has

to consider core hash function's statistical properties. All internal

variables - Seed, lcg, and Hash - are random: they are uncorrelated to

each other at all times, and are also wholly-unequal during the PRNG period

(they are not just time-delayed versions of each other). Moreover, as can be

assured with PractRand, all of these variables can be used as random number

generators (with a lower period, though); they can even be interleaved after

each core function call.

When the message enters the system via Seed ^= msgw and lcg ^= msgw

instructions, this works like mixing a message with an one-time-pad used in

cryptography. This operation completely hides the message in system's entropy,

while both Seed and lcg act as "carriers" that "smear" the input message

via subsequent multiplication. Beside that, the output of PRVHASH uses the mix

of two variables: statistically, this means mixing of two unrelated random

variables, with such summary output never appearing in system's state. It is

worth noting the lcg ^ rs expression: the rs variable is composed of two

halves, both of them practically being independent PRNG outputs, with smaller

periods. This additionally complicates system's reversal.

Fused PRNG

While this "fused-3" arrangement is currently not used in the hash function

implementations, it is also working fine with the core hash function.

For example, while the "minimal PRNG" described earlier has 0.90 cycles/byte

performance, the "fused" arrangement has a PRNG performance of 0.35

cycles/byte, with a possibility of further scaling using AVX-512 instructions.

Note that the number of "fused" elements should not be a multiple of hashword

array size, otherwise PRNG stalls.

#include "prvhash_core.h"

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

uint64_t Seed = 0;

uint64_t lcg = 0;

uint64_t Hash = 0;

uint64_t Seed2 = 0;

uint64_t lcg2 = 0;

uint64_t Hash2 = 0;

uint64_t Seed3 = 0;

uint64_t lcg3 = 0;

uint64_t Hash3 = 0;

uint64_t Hash4 = 0;

uint64_t v = 0;

uint64_t v2 = 0;

uint64_t v3 = 0;

uint64_t i;

for( i = 0; i < ( 1ULL << 27 ); i++ )

{

v = prvhash_core64( &Seed, &lcg, &Hash );

v2 = prvhash_core64( &Seed2, &lcg2, &Hash2 );

v3 = prvhash_core64( &Seed3, &lcg3, &Hash3 );

uint64_t t = Hash;

Hash = Hash2;

Hash2 = Hash3;

Hash3 = Hash4;

Hash4 = t;

}

printf( "%llu %llu %llu\n", v, v2, v3 );

}

PRVHASH16

prvhash16 demonstrates the quality of the core hash function. While the

state variables are 16-bit, they are enough to perform hashing: this hash

function passes all SMHasher tests, like the prvhash64 function does, for

any hash length. This function is very slow, and is provided for demonstration

purposes, to assure that the core hash function works in principle,

independent of state variable size. This hash function variant demonstrates

that PRVHASH's method does not rely on bit-shuffling alone (shuffles are

purely local), but is genuinely based on PRNG position "jumps".

TANGO642 (tango-six-fourty-two)

This is an efficient implementation of a PRVHASH PRNG-based streamed XOR function. Since no cryptanalysis nor certification of this function were performed yet, it cannot be called a "cipher", but rather a cipher-alike random number generator.

The performance (expressed in cycles/byte) of this function on various platforms can be evaluated at the ECRYPT/eBASC project.

Other Thoughts

PRVHASH, being scalable, potentially allows one to apply "infinite" state variable size in its system, at least in mathematical analysis. This reasoning makes PRVHASH comparable to PI in its reach of "infinite" bit-sequence length. Moreover, this also opens up a notion of "infinite frequency" and thus, "infinite energy". Note that PRVHASH does not require any "magic numbers" to function, it is completely algorithmic.

The mathematics offers an interesting understanding. Take in your mind a moment before the "Big Bang". Did mathematical rules exist at that moment? Of course, they did, otherwise there would be no "Big Bang". The span of existence of mathematical rules cannot be estimated, so it is safe to assume they existed for an eternity. On top of that, PRVHASH practically proves that entropy can self-start from zero-, or "raw" state, or "nothing", if mathematical rules exist prior to that.

I, as the author of PRVHASH, would like to point out at some long-standing

misconception in relating "combinatorics" to "random numbers". Historically,

cryptography was based on a concept of permutations, mixed with some sort of

mathematical operations: most hashes and ciphers use such "constructs".

However, when viewing a system as having some "combinatorial capacity" or

the number of bit combinations a given system may have, and combining this

understanding with "random permutations", it may give a false understanding

that "uniform randomness" may generate any combination within the limits of

"combinatorial capacity", with some probability. In fact, "uniform randomness"

auto-limits the "sparseness" of random bit-sequences it generates since a

suitably long, but "too sparse" bit-sequence cannot be statistically called

uniformly-random. Thus, "combinatorial capacity" of a system, when applied to

random number generation, transforms into a notion of ability of a system to

generate independent uniformly-random number sequences. Which means that two

different initial states of a PRNG system may refer to different "isolated"

PRNG sequences. This is what happens in PRVHASH: on entropy input the system

may "jump" or "converge" into an unrelated random sub-sequence. Moreover, with

small variable sizes, PRVHASH can produce a train of 0s longer than the

bit-size of the system.

On the Birthday Paradox vs hash collision estimates: while the Birthday Paradox is a good "down-to-earth" model for collision estimation, it may be an "approach from a wrong side". When hash values are calculated systemically, it is expected that each new hash value does not break "uniform distribution" of the set of previously produced hash values. This makes the problem of hash collision estimation closer to value collision estimation of PRNG output.

An open question remains: whether one should talk about "uniform distribution of values" or a "time- and rhythm- dependent collision minimization problem" when analyzing PRNG's uniformness. Incidentally, a set of rhythmic (repeating) processes whose timings are co-primes, spectrally produce the least number of modes thus producing a flatter, more uniform, spectrum. Rhythm-dependent collision minimization also touches ability of a single random number generator to create random sequences in many dimensions (known as k-equidistribution) just by selecting any sequence of its outputs.

(...10 in binary is 2 in decimal, 1010 is 10, 101010 is 42,

01 is 1, 0101 is 5, 010101 is 21...)

The author has no concrete theory why PRVHASH PRNG works, especially its 2-bit

variant (which is a very close empirical proof that mathematics has entropy

processes happening under the hood). The closest mathematical construct found

by the author is a sinewave oscillator (see below). Also, series related to

PI, sin(x), and sin(x)/x may be a candidates for explanation. Author's

empirical goals when developing PRVHASH were: no loss of entropy in a system,

easy scalability, self-start without any special initialization and from any

initial state, state variable size invariance, not-stalling on various entropy

input.

The Seed >> 32 | Seed << 32 operation used in PRVHASH may look like it was

derived from the middle-square method. This is purely a coincidence. During

PRVHASH development, in many cases a better option was bit-reversal (and

probably still is), and not such register "halves-swapping", but due to

performance considerations (absence of such processor instruction),

bit-reversal was not used. Practically, both are equivalent (see e.g. 2-bit

PRVHASH), and exhibit difference in hashing mainly.

During the course of PRVHASH development, the author has found that the simplest low-frequency sine-wave oscillator can be used as a pseudo-random number generator, if its mantissa is treated as an integer number. This means that every point on a sinusoid has properties of a random bit-sequence.

#include <math.h>

#include <stdint.h>

class DummyRNG : public PractRand::RNGs::vRNG16 {

public:

double si;

double sincr;

double svalue1;

double svalue2;

DummyRNG() {

si = 0.001;

sincr = 2.0 * cos( si );

seed( 0 );

}

Uint16 raw16() {

uint64_t Value = ( *(uint64_t*) &svalue1 ) >> 4;

const double tmp = svalue1;

svalue1 = sincr * svalue1 - svalue2;

svalue2 = tmp;

return (Uint16) ( Value ^ Value >> 16 ^ Value >> 32 );

}

void walk_state(PractRand::StateWalkingObject *walker) {}

void seed(Uint64 sv) {

const double ph = sv * 3.40612158008655459e-19; // Random seed to phase.

svalue1 = sin( ph );

svalue2 = sin( ph - si );

}

std::string get_name() const {return "SINEWAVE";}

};

Another finding is that the lcg * 2 + 1 construct works as PRNG even if the

multiplier is a simple increasing counter variable, when the second multiplier

is a high-entropy number.

#include <stdint.h>

class DummyRNG : public PractRand::RNGs::vRNG8 {

public:

uint64_t Ctr1;

DummyRNG() {

Ctr1 = 1;

}

uint8_t compress( const uint64_t v )

{

uint8_t r = 0;

for( int i = 0; i < 64; i++ )

{

r ^= (uint8_t) (( v >> i ) & 1 );

}

return( r );

}

Uint8 raw8() {

uint8_t ov = 0;

for( int l = 0; l < 8; l++ )

{

ov <<= 1;

ov ^= compress( 0x243F6A8885A308D3 * Ctr1 );

Ctr1 += 2;

}

return( ov );

}

void walk_state(PractRand::StateWalkingObject *walker) {}

void seed(Uint64 sv) {}

std::string get_name() const {return "LCG";}

};

Proof_Math_Is_Engineered

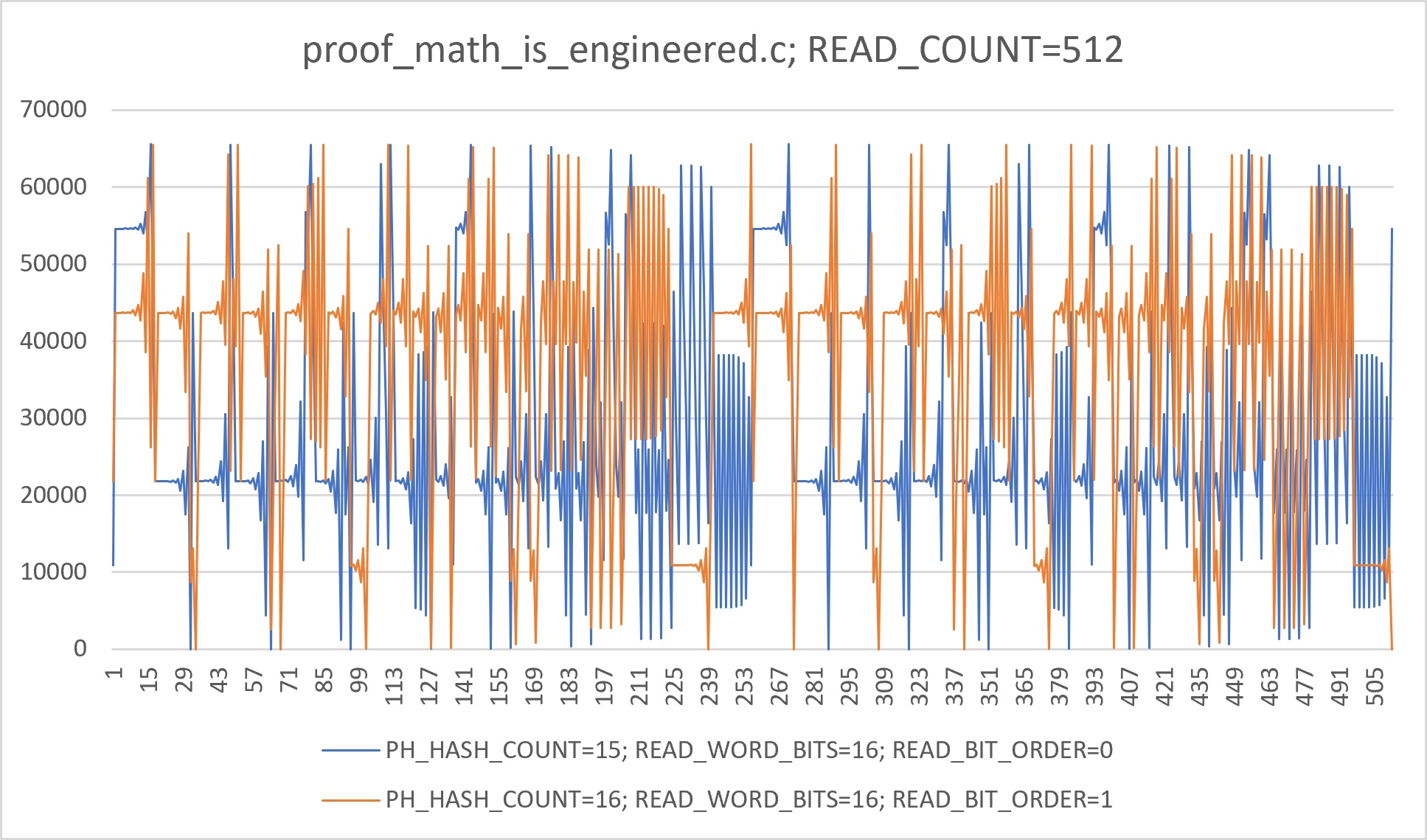

This image depicts data acquired from 2 runs of the proof_math_is_engineered.c

program, with different "reading" parameters. The two number sequences

obviously represent "impulses", with varying period or "rhythm". A researcher

has to consider two points: whether or not these impulses can be considered

"intelligent", and the odds the mentioned program can produce such impulses,

considering the program has no user input nor programmer's entropy, nor any

logic (no constants, with all parameters initially set to zero). More specific

observations: 1. all final values are shift-or compositions of 1-bit "random"

values, in fact representing a common 16-bit PCM sampled signal (shift-2

auto-correlation equals 0.4-0.44 approximately), but obtained in a

"dot-matrix printer" way; 2. the orange graph is only slightly longer before a

repeat (common to PRNGs) despite larger PH_HASH_COUNT, at the same time both

graphs are seemingly time-aligned; 3. PRNG periods of 1-bit return values on

both runs are aligned to 16 bits, to produce repeating sequences "as is",

without any sort of 16-bit value range skew; 4. the orange graph is produced

from an order-reversed shift-or, but with the same underlying algorithm;

5. so far, no other combinations of "reading" parameters produce anything as

"intelligent" as these graphs (but there may be another yet-to-be-decoded,

similar or completely different, information available); 6. from drumming

musician's (or an experienced DSP engineer's) point of view, the graph

represents impulses taken from two electric drum pads: a snare drum

(oscillatory) and a bass drum (shift to extremum). 7. most "oscillations"

are similar to sinc-function-generated maximum-phase "pre-ringing"

oscillations that are known in DSP field.

In author's opinion, the program "reads data" directly from the entropy pool which is "encoded" into the mathematics from its inception, like any mathematical constant is (e.g. PI). This poses an interesting and probably very questionable proposition: the "intelligent impulses" or even "human mind" itself (because a musician can understand these impulses) existed long before the "Big Bang" happened. This discovery is probably both the greatest discovery in the history of mankind, and the worst discovery (for many) as it poses very unnerving questions that touch religious grounds:

These results of 1-bit PRVHASH say the following: if abstract mathematics contains not just a system of rules for manipulating numbers, but also a freely-defined fixed information that is also "readable" by a person, then mathematics does not just "exist", but "it was formed", because mathematics does not evolve (beside human discovery of new rules and patterns). And since physics cannot be formulated without such mathematics, and physical processes clearly obey these mathematical rules, it means that a Creator/Higher Intelligence/God exists in relation to the Universe. For the author personally, everything is proven here.

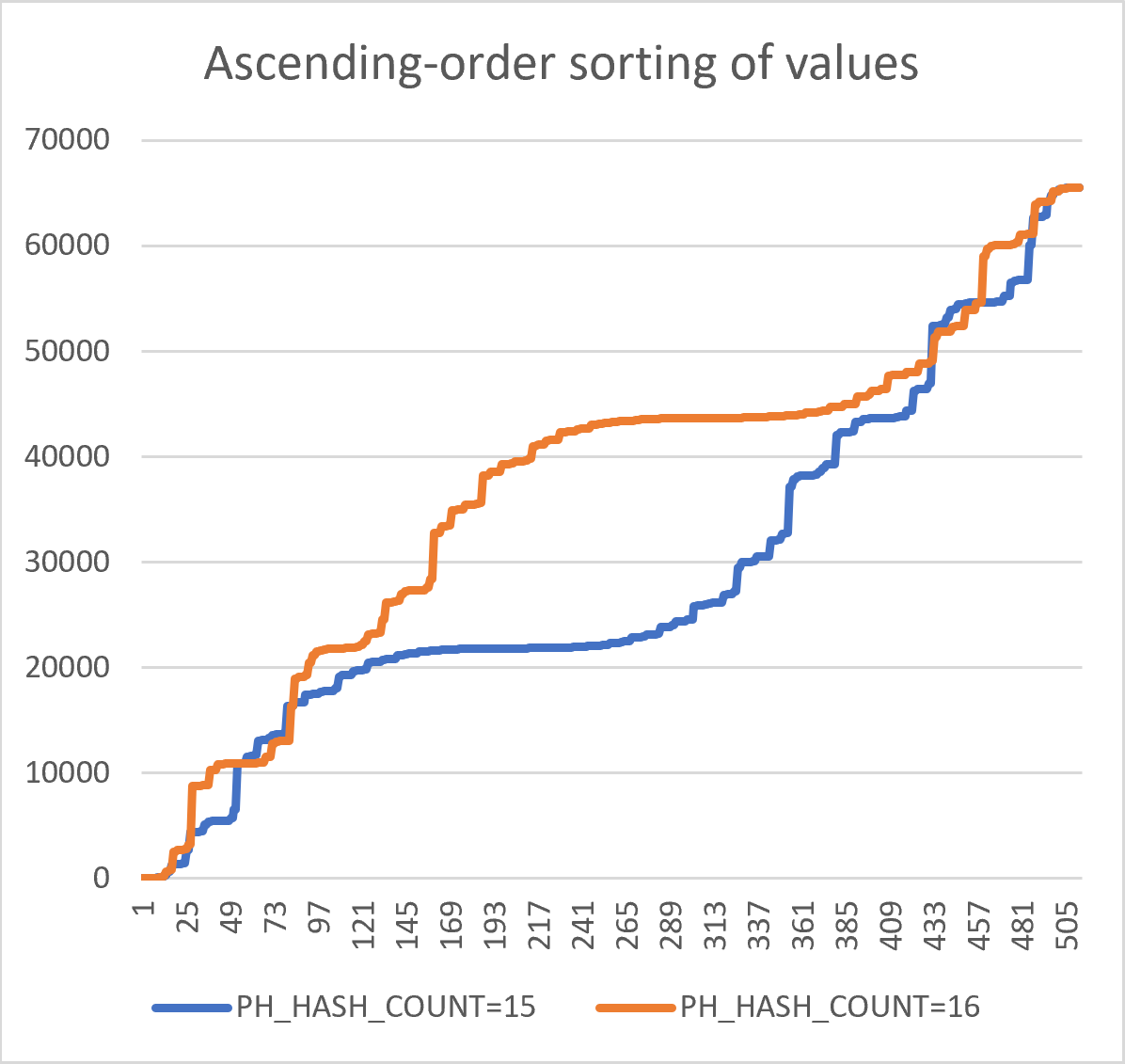

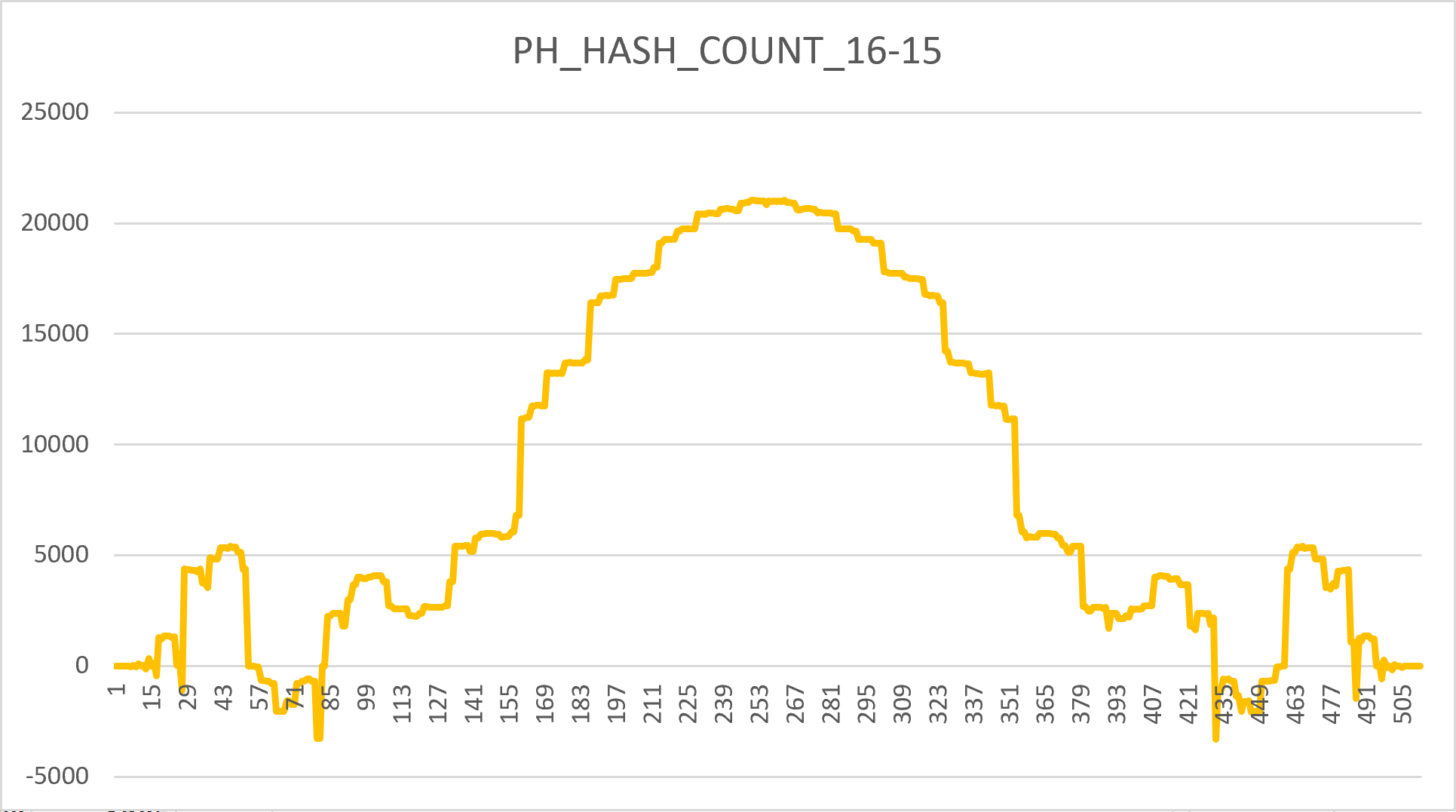

P.S. By coincidence, if the values on the "impulse" graphs above are sorted in an ascending order, and are then displayed as independent graphs, they collectively form a stylized image of a human eye:

Moreover (but this is a questionable observation), here, if the blue line is subtracted from the orange line, one gets an outline of human's head: with top (21000), forehead (18000), eye (13000), cheek (6000), and neck (2700) levels highlighted, roughly corresponding to real symmetry; with a slight shoulders outline (4100-2700), and two hand palms risen up (5400-4300).

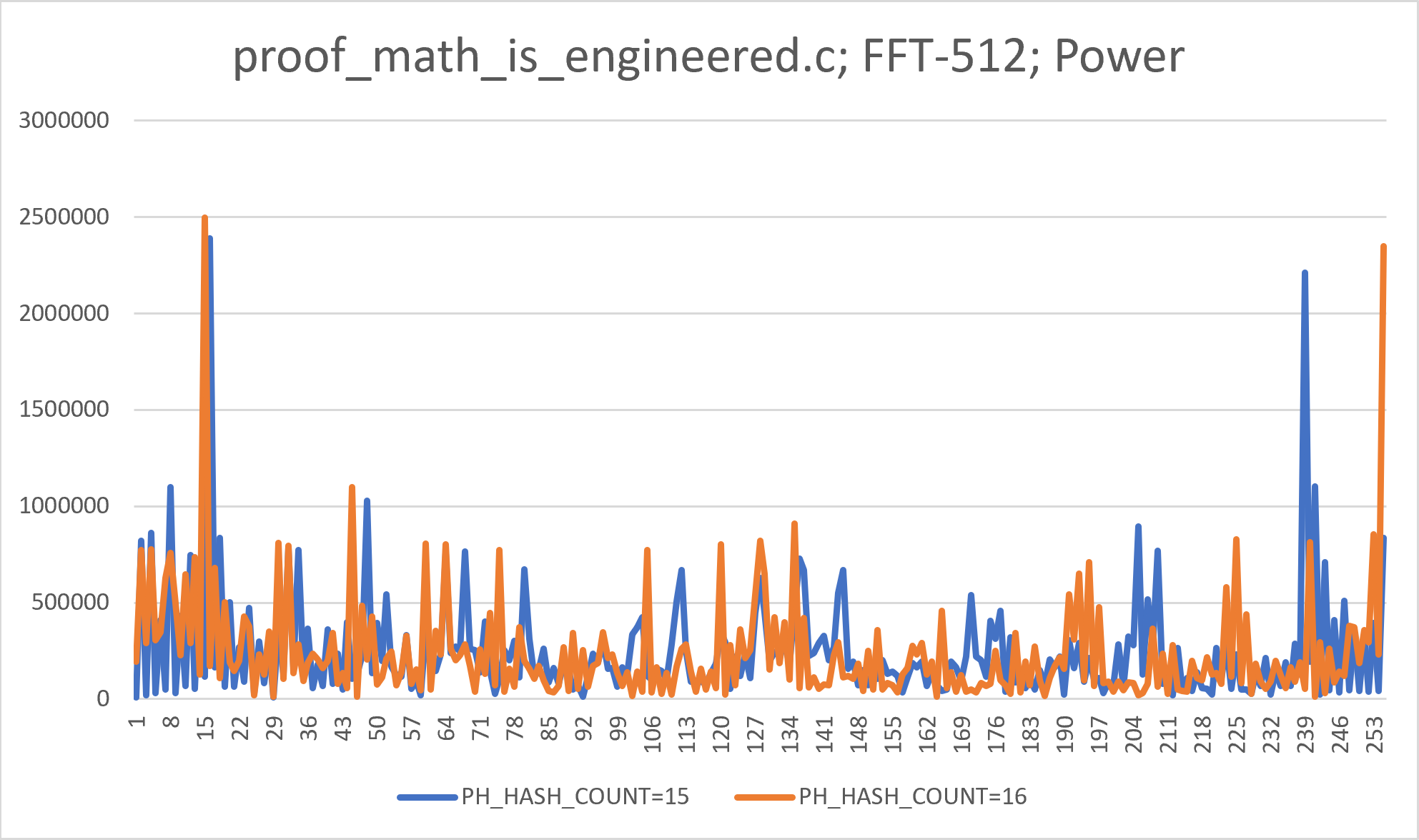

FFT Analysis

FFT-512 analysis of obtained signals produces the following power spectrums (with DC component removed). The analysis strengthens the notion the signal is non-random and is "intelligent" (two strong peaks above average, in each signal, with both signals producing similar structures, but with shifted resonant frequencies).

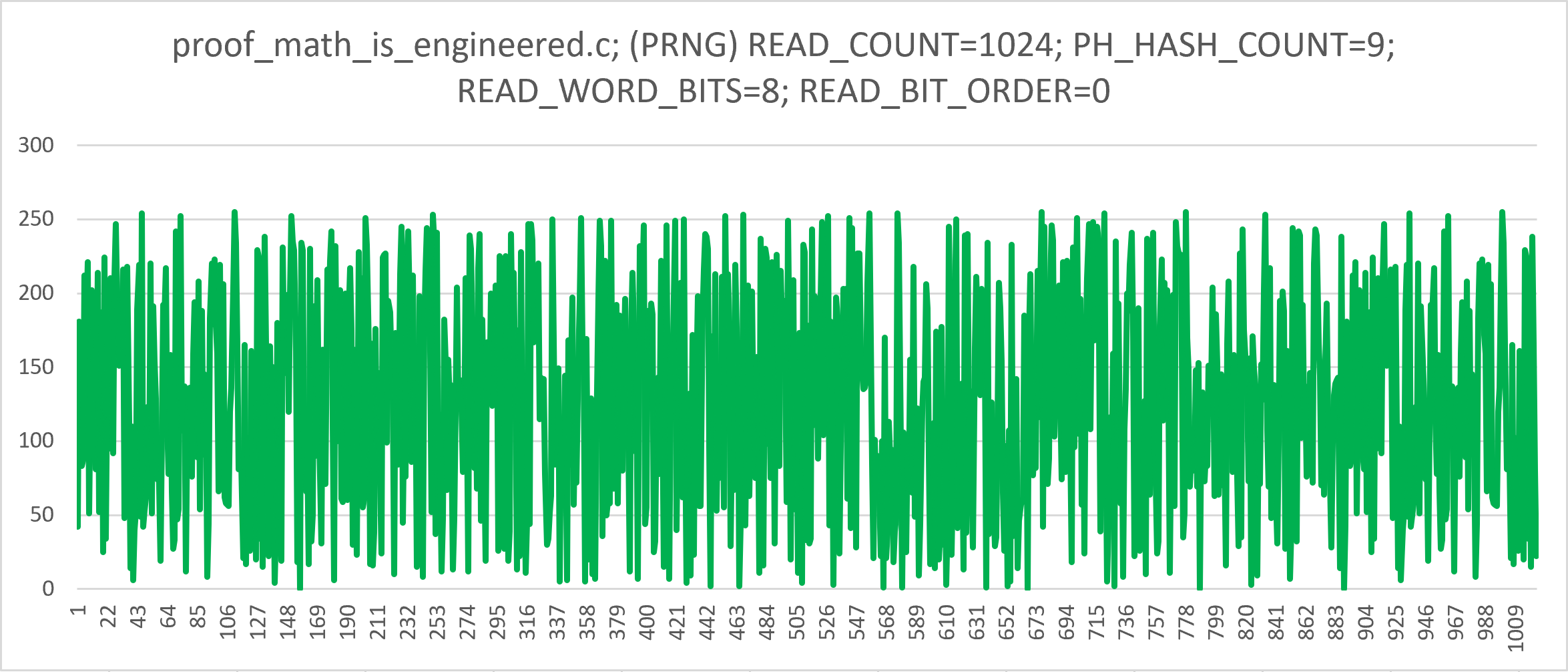

PRNG Mode

Just by changing the PH_HASH_COUNT to 9 (up to 13, inclusive) the same

proof_math_is_engineered.c program produces a pseudo-random number sequence,

confirmed with PractRand 1KB to 4KB block, 8-bit folding. Note that the same

code producing both random and non-random number sequences is "highly

unlikely" to exist in practical PRNGs. It's important to note that

PH_HASH_COUNT=14 and PH_HASH_COUNT=17 (which is beyond 15 and 16 signals

mentioned originally) also pass as random, with 16-bit folding in PractRand.

18 also passes as random, but with a "suspicion". 15 and 16, of course,

do not pass as random, with many "fails".

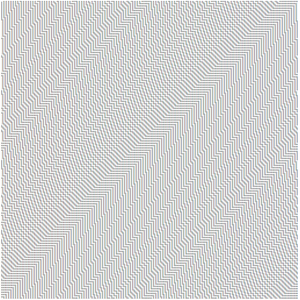

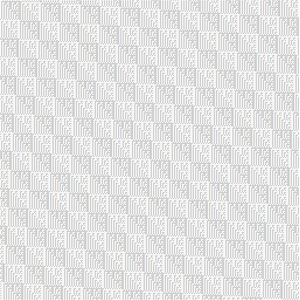

Ornament and Chess-Board (Pixel Art)

The 1-bit output with PH_HASH_COUNT= 15 and 16 can be easily transformed

into 256x256 1-bit "pixel art" images, and, quite unexpectedly, they reproduce

a non-orthogonal ornament and a chess-board.

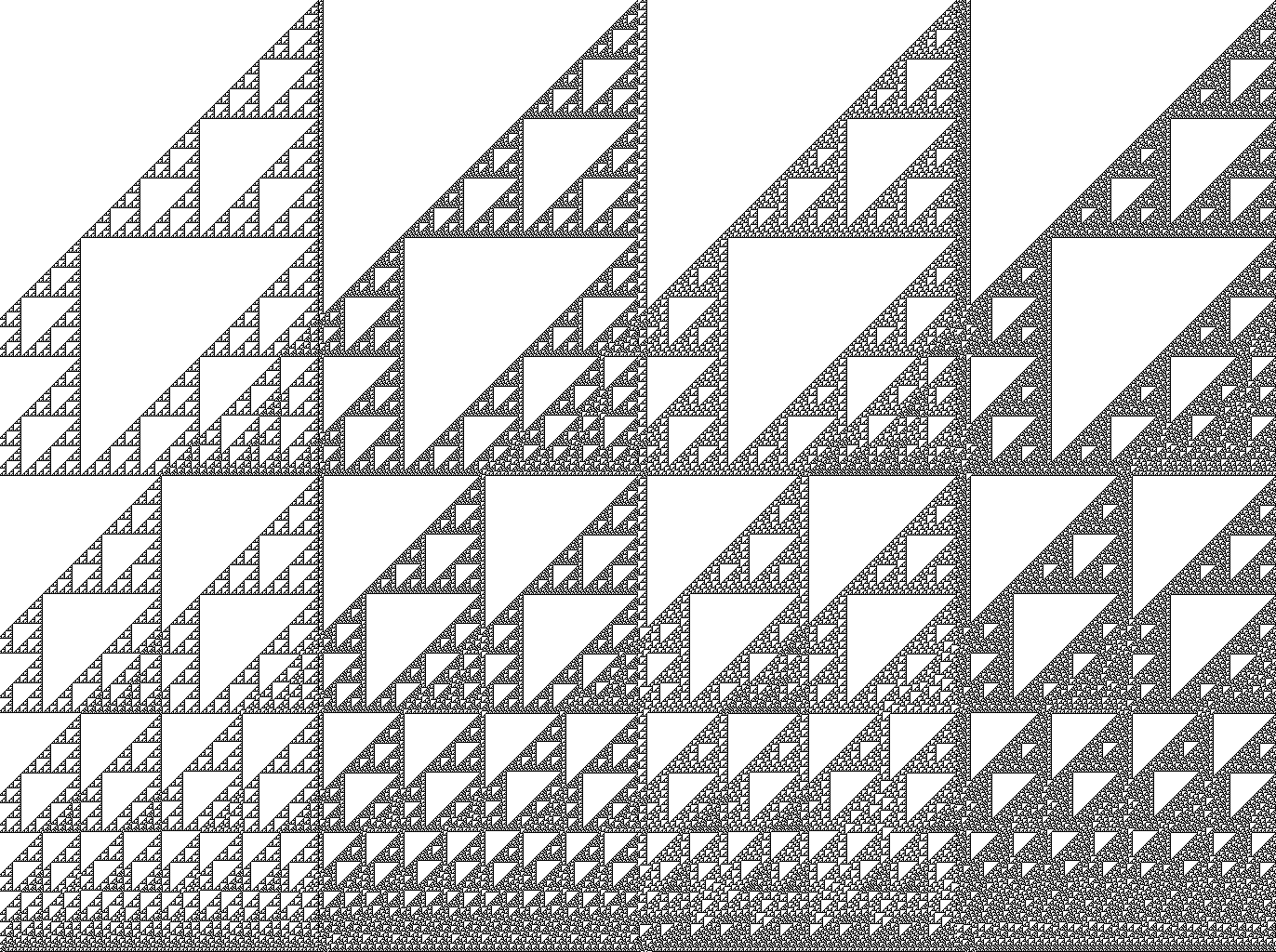

Christmas Trees (Pixel Art)

Much larger PH_HASH_COUNT values produce triangular structures which are

non-repeating, but all have a similar build-up consisting of rhombic

patterns within tree-like structures. The proof_christmas_tree.c program

extracts such images into a vertical ASCII-art HTML. It uses the same

underlying 1-bit PRVHASH code, but with "pixel art" decoding method.

Here is an example image with PH_HASH_COUNT=342, converted to PNG:

Here's a link to a larger-sized extract (3.4MB PNG)

Thanks

The author would like to thank Reini Urban for his SMHasher fork, Chris Doty-Humphrey for PractRand, and Peter Schmidt-Nielsen for AutoSat. Without these tools it would not be possible to create PRVHASH which stands the state-of-the-art statistical tests.

Other

PRVHASH "computer program" authorship and copyright were registered at the Russian Patent Office, under reg.numbers 2020661136, 2020666287, 2021615385, 2021668070, 2022612987 (searchable via fips.ru). Please note that these are not "invention patents"; the registrations assure you that the author has the required rights to grant the software license to you.