Lindley-X is a scrappy, highly experimental project that sets out to explore the following question: to what degree is it possible to reliably model the features that tend to suggest that a legal judgment is "significant"?

In common law systems (e.g. the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the USA), there are two primary sources of law.

The first primary source of law is legislation passed by a legislative body (e.g. Parliament). Legislation is effectively a list of written rules bearing on a particular subject that have been bundled into a single document (e.g. the Human Rights Act 1998).

The second primary source of law, which is the focus of ICLR&D's broader research efforts and this project, is the law made by judges in the courts when deciding the cases before them. Law made by judges is termed common law. The driving mechanism behind the common law is the doctrine of precedent, which holds that judges should decide questions of law in a way that conforms with the legal decisions in earlier cases that engaged the same or similar legal issues. Unless a court has special status, it is bound to follow applicable earlier decisions given by courts of higher or equal standing.

In the vast majority of cases heard in mature common law systems the legal issues to be decided will be governed by established principles carved out by earlier cases (sometimes very, very old cases). The effect of this is that the vast majority of cases are decided by applying existing precedent to the facts; there is no need for the court to create new law. However, in a significant minority of cases it will be necessary for the courts to create new law - to set a new precedent - because the case before them engages issues to which existing legislation and common law principles do not apply.

The number of judgments given in the senior courts in England and Wales (the High Court, the Court of Appeal and the UK Supreme Court) runs to between 7,500 and 9,000 annually. The quantity isn't colossal, but it presents a problem of profound importance to lawyers and researchers in common law systems: how do we sort the needles (the cases that set a new precedent) from the haystack (the vast majority of cases that do not set a new precedent)?

The problem of identifying precedent-setting cases is probably as old as the common law itself, at least in England and Wales. If we jump back in time to the mid-1800s, the process of "reporting" important cases in England was left to the private sector; lawyers, generally as a means to earn some extra cash, would publish their notes of cases they regarded as being of precedential value in expensive leather-bound volumes. The coverage given to the common law at that time was patchy, costly, glacially slow and frequently inaccurate.

In the 1860s a group of senior lawyers and judges gathered in London in attempt to sort the mess out. The solution they devised was the establishment of an organisation tasked with monitoring the courts, identifying cases that set new precedents and reporting those cases clearly and accurately. That organisation was the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales (ICLR), which was formally established in 1865 and started publishing in 1866.

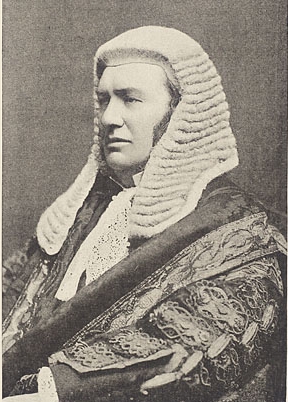

One of the central pillars of the newly formed ICLR was it's "criteria of reportability" - the set of tests it would apply to determine whether a new case set a new precedent. The criteria applied by ICLR in 1865 right up to the present day was devised by Lord Lindley, an English barrister who would go on to become Master of the Rolls and a law lord in the Judicial Committee of the House of Lords.

This first thing Lord Lindley did was to define what was not a precedent:

... cases that passed without discussion and were valueless as precedents, and those that were substantially repetitions of earlier reports

A case was unlikely to be regarded as setting a new precedent if it effectively involved a straightforward application of existing law.

He then went on to define four classes of cases that would be regarded as being significant:

- All cases which introduce, or appear to introduce, a new principle or a new rule.

- All cases which materially modify an existing principle or rule.

- All cases which settle, or materially tend to settle, a question upon which the law is doubtful.

- All cases which for any reason are peculiarly instructive.

For the past 154 years, ICLR has been applying these criteria to all of the cases it has covered. The criteria are applied by a qualified lawyer, a law reporter, who has covered the case in court and carefully analysed the judgment. For each case the law reporter is assigned to consider, a binary decision falls to be taken: does the case fulfil Lord Lindley's criteria of reportability? If the answer to that is "yes", then a report is produced. If the answer to that is "no", then no further action is taken.

Accordingly, the question at the core of Lindley-X is whether we can train a model on ICLR's decision to report or not to report in order to automatically carry out a similar analysis.

ICLR's modern approach to law reporting boils down to the following steps:

- The raw judgment given in a case will be published on iclr.co.uk regardless of whether the case is reportable or not.

- In the event that the case is assessed as being reportable according to the Lindley criteria, a report will be produced and published in one of ICLR's five series of law reports.

The Lindley-X model therefore made the following assumptions:

-

The presence of the raw judgment along with a fully reported version of the case was taken as a signal that the case was significant.

-

The presence of the raw judgment but the absence of a fully reported version of the case was taken as a signal that the case was not significant.

The presence or absence of a law report provided a convenient method for gathering labelled examples for both classes for the binary classification task Lindley-X is directed towards. The intuition driving our approach feature extraction approach was that significant cases bear qualities that can be quantitatively evaluated that less significant cases inherently lack.

Our assumptions were as follows:

- The presence of "legal entities", such as references to case law, would be proportionately higher in significant cases by reference to the length of the judgment than less significant cases.

- By virtue of the fact that significant judgments have a tendency to be more common where judgment was reserved and handed-down in writing and less significant judgments would be given orally and extemporaneously, significant cases would tend to be longer than less significant cases.

Crucially, we were keen to avoid extracting features that would require the training material to be in a structured form - the feature extraction would be based exclusively on components that could be gleaned from the training data without recourse to parsing a marked-up version of the judgments. A strategy dependant on pre-existing markup would render the model useless to pretty much everyone outside of ICLR. For this reason, our feature engineering strategy did not include two features that were assumed to of value to the model:

- the court giving judgment

- the number of judges (or, the bench strength)

All of the feature extraction was handled probalistically by applying the prototype Blackstone model to the judgment text. The features included in the model are as follows:

- the total number of tokens in the judgment (words and punctuation marks)

- the total number of entities identified in the judgment by Blackstone

- the percentage of merged entity tokens to the overall token count (

total entities / total tokens) - the number of case citations in the document identified by Blackstone

- the total number of sentences identified by Blackstone

- the total number of sentences categorised by Blackstone as postulating an axiom

- the total number of sentences categorised by Blackstone as postulating a conclusion

- the total number of sentences categorised by Blackstone as discussing an issue in the case

- the total number of sentences categorised by Blackstone as discussing a legal test

- the total number of uncategorised sentences

- the total number of sentences categorised as an axiom, conclusion, issue or legal test

- the percentage of sentences categorised as an axiom, conclusion, issue or legal test to the total number of sentences in the judgment

Note it is strongly recommended that you follow these installation instructions from within a clean virtual environment.

- Run the following command:

python3 -m venv lindley-x

- Activate the virtual environment:

source lindley-x/bin/activate

- Clone this repository

- Navigate to the repository directory:

cd Lindley-X - Install the dependencies:

pip install -r requirements.txt(apologies are due here, therequirements.txtfile is really bloated -- we will fix this) - Install the Blackstone model:

pip install https://blackstone-model.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/en_blackstone_proto-0.0.1.tar.gz

Lindley-X is executed from the command line and takes three positional arguments:

-

input_dirwhich is the path to a directory consisting of one or more judgments in plain-text format. -

modelwhich is the path to the Lindley-X model stored in this repo'smodeldirectory -

output_filewhich is the path to a.csvfile the model's predictions are written to

The Lindley-X model is applied from the command line, like so:

python3 apply_model.py path/to/text/files path/to/the/model path/to/output/csv/file

For example,

python3 apply_model.py /sample_data /model/lindley_x_model.pkl my_predictions.csv