_____ _______ __ __

| | |----.-.-.-. | | |.-----.--| |__|.---.-.

| | -__| | | | | || -__| _ | || _ |

|_|___|____|_____| |__|_|__||_____|_____|__||___._|

_____ _______ __ __

| | |----.-.-.-. |_ _|.-----.----.| |--.----.----.| |.-----.-----.--.--.

| | -__| | | | | | | -__| __|| | | _ || || _ | _ | | |

|_|___|____|_____| |___| |_____|____||__|__|_|__|____||__||_____|___ |___ |

|_____|_____|

Leiden University 2016 // Peter van der Putten // Jeroen Oorschot

For this assignment I experimented with raymarching signed distance fields. A methodology for creating graphics with pixel shaders that run on the GPU of your computer.

For people not wel versed in coder-geek speak; A fancy screensaver with tunnels and pretty colors.

Raymarching is a technique that has gained quite some popularity with graphics enthouisast programmers (read; demoscene coders) for its simplicity and its speed.

Imagine you and your monitor being placed into a virtual world. The eye is looking at the monitor (a rectangle), we'll name this rectangle the 'image plane'. By casting rays from the eye to the image plane, we can determine the direction of each ray. With its direction, we march along the ray (hence the term raymarching), in discrete steps. Every step, we check if we're close enough to a surface. This is done by evaluating a distance function. The distnace function returns a distance with is signed (negative or positive) depending on whether we're inside, or outside the object.

Many of these distance functions were collected by Inigo Quilez, and can be found here.

Distance functions can not only be used to define primitive objets, but also:

- operations on these object (union, subtraction, intersection)

- domain operations (repetition, rotation, scaling)

- deformations (displacements, blends and twists)

In order to limit my exposure to all different options, I limited myself to spheres, subtractions and repetitions, as those in combination were already complex enough to wrap my head around.

The main functions of the standard open frameworks apps that were used were setup(), update(), and keyReleased(). To handle the incoming OSC data a handleOSC() function was written.

void ofApp::setup(){

cout << "listening for osc messages on port " << PORT << "\n";

receiver.setup(PORT);

ofSetFrameRate(60);

#ifdef TARGET_OPENGLES

shader.load("shadersES2/shader");

#else

if(ofIsGLProgrammableRenderer()){

shader.load("shadersGL3/shader");

}else{

shader.load("shadersGL2/shader");

}

#endif

}

The main setup functions takes care of the following housekeeping bits:

- It sets up OF (receiver) for listening to OSC messages on its server

- Sets the framerate to a snappy 60 frames a second

- Loads the appropriate shader based on TARGET_OPENGLES (different GPU’s use different versions of OpenGL)

Every update OF handles the incoming data via OSC:

void ofApp::update(){

while(receiver.hasWaitingMessages()) {

handleOSC();

}

}

A separate function was written to handle the incoming OSC data.

void ofApp::handleOSC() {

ofxOscMessage m;

receiver.getNextMessage(m);

cout << m.getArgAsFloat(0) << "\n";

/*

* Yes, I'm a aware that this is a ton of copy-paste. it gets the job done though ^_^

*/

if (m.getAddress() == "/midi/cc21/9") {

c0 = m.getArgAsFloat(0);

}

…

if (m.getAddress() == "/midi/cc48/9") {

c15 = m.getArgAsFloat(0);

}

}

handleOSC gets OSC messages from the OSC receiver and passes it along to the appropriate variable defined in OF. Quite some copy paste, but it gets the job done.

We’re also watching input on the keyboard. It’s only to get our App to run full-screen, but hey, for thorough documentation:

void ofApp::keyReleased(int key){

switch (key) {

case 'f':

ofToggleFullscreen();

break;

default:

break;

}

}

With all of that out of the way, let’s have a look at the draw() function, since people would assume that is where most of the action happens…

void ofApp::draw(){

ofSetColor(255);

ofHideCursor();

shader.begin();

/*

* move my OSC inputs into the shader

*/

shader.setUniform1f("c0", c0);

…

shader.setUniform1f("c15", c15);

/*

* get the OF time into the shader

*/

shader.setUniform1f("ofTime", ofGetElapsedTimef());

/*

* get the screenResolution into the shader

*/

shader.setUniform2f("ofResolution",ofGetWidth(),ofGetHeight());

ofRect(0, 0, ofGetWidth(), ofGetHeight());

shader.end();

}

As you can see, nothing much is happening over here, we’re just drawing a rectangle with the size of the screen each frame. However, we are running a shader on that rectangle every frame, see below for more info on how that’s done…

Before we get into the intrecacies of shaders, let's look at how OpenFrameworks works. It's a framework written in C++, which means it gets compiled into machinecode when compiling. This is what gives it its speed (compared to say Processing, although their OpenGL support has improved over the past few releases). However, it also presents a problem, its compile-view-tweak-compile cycle is notably longer than Processing, and that makes it slow to tweak stuff while you're experimenting.

In order to have some parameters to tweak, I figured I could use one of my MIDI controllers. I normally use these for tweaking the parameters of soft-synths (VST's), but why wouldn't they be suited for manipulating the values of shaders?

OpenFrameworks has support for sending and receiving OSC (Open Sound Control) data thru OfxOSC, so I included that external library when generating the project using the project generation.

All that was left was to find a way to get my MIDI data into a proper OSC format...

Osculator is a neat OSX based piece of software that helps with the translation of incoming midi data to OSC data. It translates incoming midi data of any configured device and allows the user to determine how this data should be pased along as OSC. One of the nicer things about OSC, being a modern protocol that it's not tied to 7 bits of data like MIDI is, this means that controller data is from my MIDI controller as a normalized value (between 0 and 1), which makes it convenient to control paramters with.

I used a Novation Launchcontrol as my midicontroller. It has 16 knobs that output midi CC values as well as 8 push pads and several control buttons. All midi assignments can be re-assigned thru provided software, but as I was only using the 16 knobs, I stayed with their default midi CC values.

With OSC properly set up, it was just a matter of putting OSC data into appropriate float variables that I defined. An array would have also sufficed, but the control data needed to be passed from OF to the shader as well. In this case having a 1 to 1 relation between the OSC message, OF float, and Shaderfloat was a convenient way of setting things up, although you incur a lost of copy-paste code.

Other OF variables getting passed into the shader include the current screen resolution (which we need when writing the fragment shader), as well as the value of the timer (otherwise we wouldn't be able to animate anything in the shader).

With all of the setup and input of control data out of the way, let's have a look at the part where the actual graphics are created. This is done using 'shaders' Shaders can be thought of a little programs that run on your GPU (Graphic Processing Unit) that determine how your computer draws something. It's important to realize that these shaders are not running on your CPU, and that their API (GLSL) is not part of Open Frameworks.

Shaders are also part of WebGL, and as such can run in your browser. The popular website ShaderToy allows you to experiment with shaders in your browser. Please be aware that the site makes heavy use of your GPU, so vistiting it with an onboard GPU instead of a discrete GPU, can seriously hamper the performance of your browser, making your system unresponsive.

Since OF uses Shader Model 3, there are two shaders running, a Vertex Shader, that operates on 3D geometry, and a Fragment shader that runs on the 'fragments' (i.e. pixels) of the image that we're generating.

uniform mat4 modelViewProjectionMatrix;

in vec4 position;

void main(){

gl_Position = modelViewProjectionMatrix * position;

}

Our vertex shader takes care of changing the coordinates in 3D space, to 2D space, using the Model View Projection matrix. It outputs these to the fragment shader.

The fragment shaders operate on the actual pixels of the image. It's important to note that each fragment shaders operates in parralel on the pixels of the image.

This is where we do our actual raymarching, and work with signed distance fields. Since this is where the main action happens in this project, I've chopped it into discrete elements that I'll discuss as we go along.

uniform float c0,c1,c2,c3,c4,c5,c6,c7,c8,c9,c10,c11,c12,c13,c14,c15;

uniform float ofTime;

uniform vec2 ofResolution;

First we define the variables that we get from OF. Keep in mind that these are updated every frame. We get the control values from OSC (c0 thru c15), get the value of the ofTimer, and we store the resolution of the OF window in a 2D vector.

out vec4 fragColor;

A fragmentshader always has to output a pixelcolor. This color is defined in a 4D vector, where the four dimensions map to a RGBA (32bit) pixel value. They range from 0 to 1 (in contrast to 0...255 that most people are familar with from web design), and an Alpha value, defining the transperacy of the pixel.

const float PI=3.14159265358979323846;

We keep a constant of PI with an appropriate number of decimal places, which we'll use in different spots.

float speed=ofTime*1.5;

We define a speed by multiplying with the current time

float plane_x= cos(PI + speed*0.25);

float plane_y= -0.2;

float plane_z= 2+speed*0.5;

Next, we define a an image plane. We update the position of the image plane on every frame.

vec2 rotate(vec2 k,float t)

{

return vec2(cos(t)*k.x-sin(t)*k.y,sin(t)*k.x+cos(t)*k.y);

}

This is a small utility function for rotating 2D vectors.

float obj(vec3 p)

{

float ball_p=1.0;

float ball_w=ball_p*(0.6650-0.075*0.02);

float ball=length(mod(p,ball_p)-ball_p*0.5)-ball_w;

float hole_w=ball_p*(0.825);

float hole=length(mod(p,ball_p)-ball_p*0.5)-hole_w;

return max(-ball,hole);

}

Here we define our 'scene'. We define spheres which we repeat using the mod() operation. We then subtract another sphere (with a smaller spacing) from the larger set of spheres, resulting in the final surface.

void main()

{

vec2 position=(gl_FragCoord.xy/ofResolution.xy);

vec2 p=-1.0+2.0*position; // limit range to -1 ... +1;

We calculate the position of the current pixel by dividing the Fragment coordinate by the resolution of the OF window. After that we limit the range of those positions between -1 and +1 on both axis.

vec2 aspectRatio = vec2(ofResolution.x/ofResolution.y,1.0); // aspect ratio so we're nice and square on every resolution

We calculate the aspect ratio, by dividing the width by the height (assuming our screen is wider than it's tall). This will help us keep our viewport nicely proportional across different window sizes and resolutions.

vec3 vp=normalize(vec3(p*aspectRatio,0.80)); // screen ratio (x,y) fov (z) (viewport)

Create a normalized rectangle that covers the viewport

vp.xy=rotate(vp.xy,speed*0.5); // rotate along z

We rotate the viewport along the z axis, makes for a dynamic camera :-)

vec3 ray=vec3(plane_x,plane_y,plane_z);

Create a ray with the image plane.

float t=0.0;

t steps along the ray

const int ray_n=96;

Here we limit our maximum number of steps

for(int i=0;i<ray_n;i++)

{

float k=obj(ray+vp*t);

here we test our ray with our scene (defined as distance functions defined in obj)

if(abs(k)<0.002) break;

If our steps become to small, we step out

t+=k*0.7;

Take a step along the ray

}

vec3 hit=ray+vp*t;

With our hit surface

vec2 h=vec2(-0.05,0.05); // light

create some light

vec3 n=normalize(vec3(obj(hit+h.xyy),obj(hit+h.yxx),obj(hit+h.yyx)));

calculate the surface normal

float c=(n.x+n.y+n.z)*0.08+t*0.16; // shade

shade the object

float color=-0.25*cos(PI*position.x*2.0)+0.25*sin(PI*position.y*4.0);

caculate a radial gradient based on the pixel position

float r = c*1.25-color;

float g = c*1.25;

float b = c*1.5+color;

float a = 1.0;

vary the amounts of red and blue based on the distance from the center.

fragColor=vec4(vec3(r,g,b)*c,a);

output the color from the shader.

}

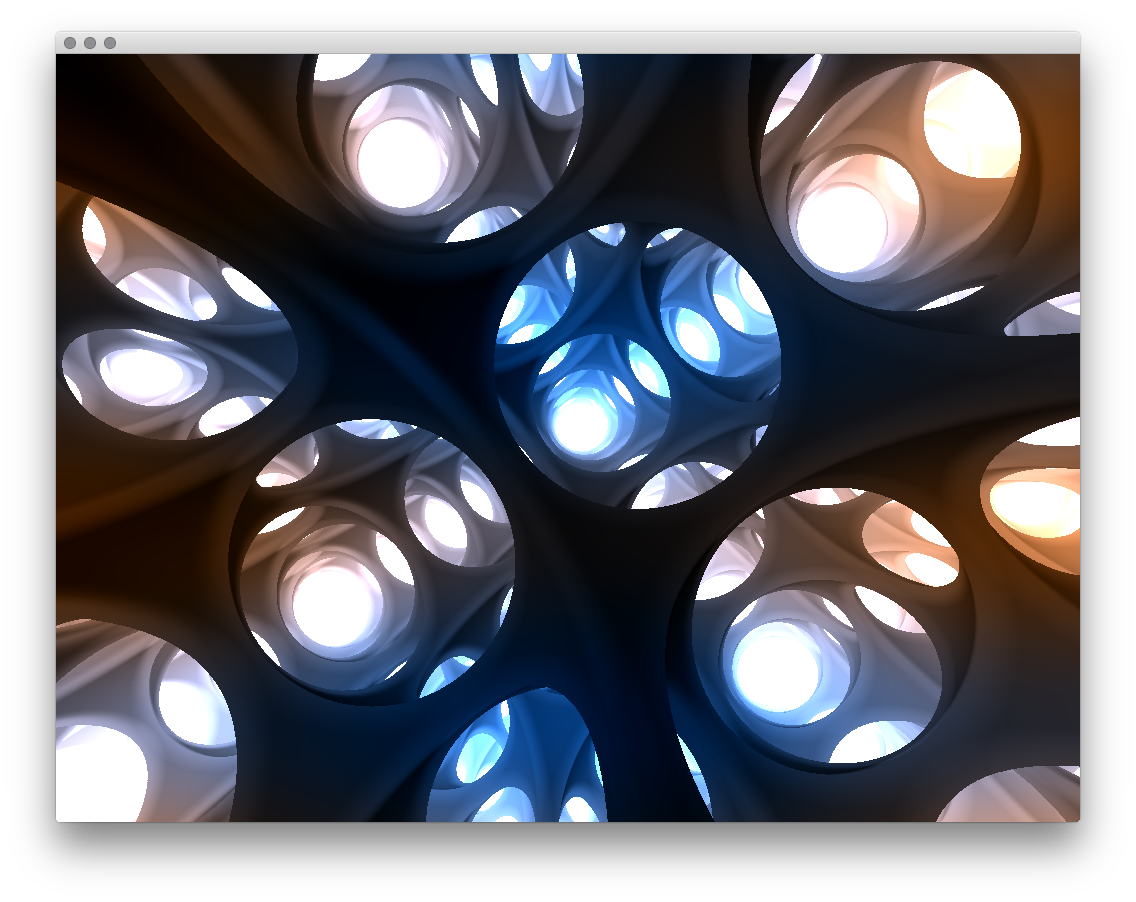

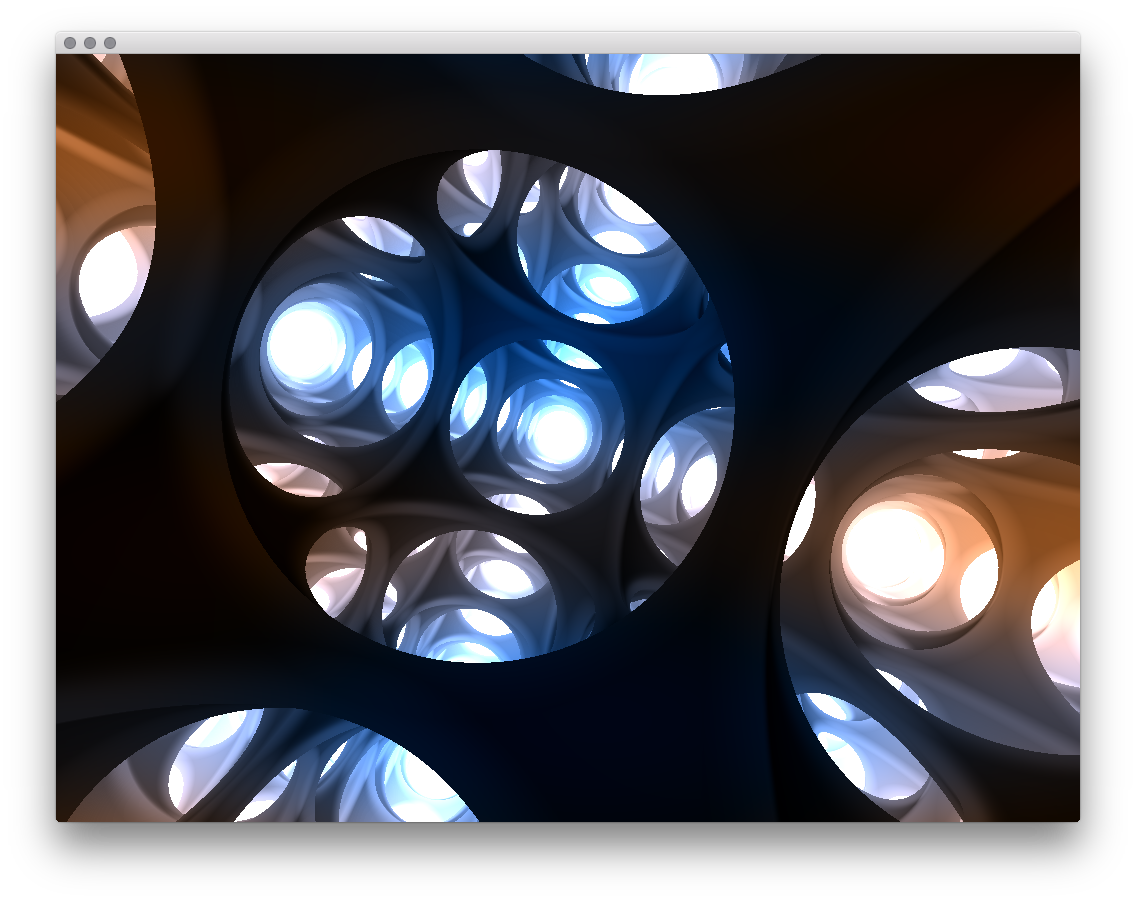

some screencaptures:

Dunn, F., & Parberry, I. (2011). 3D Math Primer for Graphics and Game Development, 2nd Edition. CRC Press.