This project is an extension of a previous repo (SFMLHitbox) where the goal is to create an easily implemented object that allows for accurate hitbox detection on both convex and concave shapes. By default, SFML only has a ConvexShape, for which there is no intersects function.

A Polygon object can be created in three different ways:

- By providing a texture to the constructor which will identify important pixels to be included as vertices and create the shape based on these. This will also allow for the user to define the level of accuracy as either pixel perfect or varying levels of approximate.

- By providing a vector of pre assembled vertices, possibly from some other SFML class by using the getPoints() method.

- By directly passing in any of the SFML shape objects (CircleShape, RectangleShape, ConvexShape), whose vertices will be used

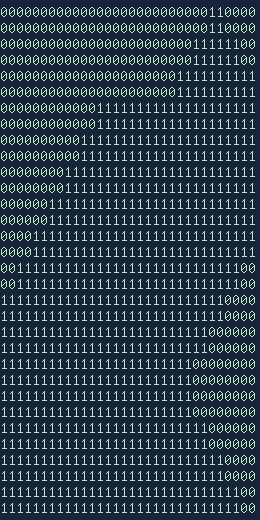

Shown above is a sample of the intersection method, which relies on defining the boundary of each shape as a set of lines, and detecting intersections amongst them.

What it can do so far:

- Create a set of vertices from an image file with a varying level of detail to optimize the number of vertices (given by the user)

- Draw the object and use common SFML transformations (rotate, scale, move)

- Detect intersection between Polygon type and any other SFML shape regardless of concavity (without providing resultant vector)

What is being worked on currently:

- Detecting whether one shape is inside of another

- Sometimes when a shape has too sharp of edges, the shape detection breaks

- Setting up objects in a k-d tree to optimize collision detections

- Resolving collisions by moving each shape appropriately (for non-circles)

- Optimizing vertex reduction for objects even more

- General refactoring, cleaning up code, and documentation

There are several aspects to how this library will work, many of which are complicated and so will be overviewed below. This information is not necessary to use the tool, but can be helpful to understand what is going on (especially if you want to contribute to the code).

For information on practical usage of the tool, see the documentation page.

This isn't so much mathematical as it is programmatic. This section of code can be found in the polygon constructor that takes in a texture, a level of detail, and an optional list of colors.

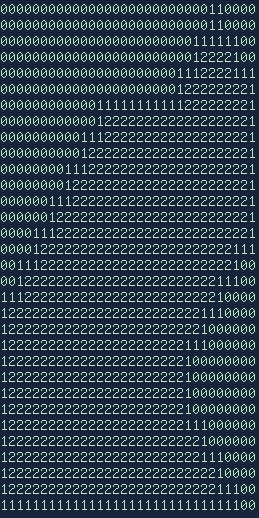

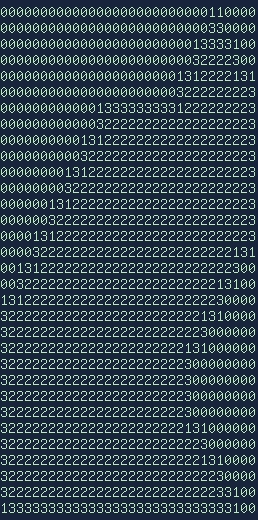

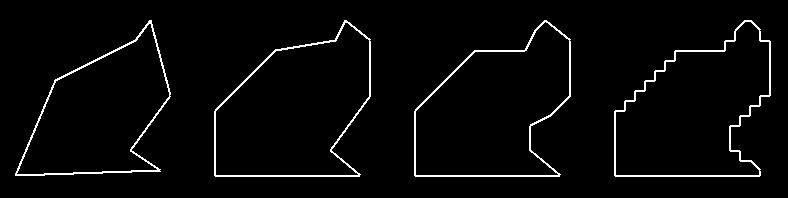

The notation for images below is as follows

- 0 denotes empty space (will not be included)

- 1 denotes a vertex that will be included

- 2 denotes the inside of a shape that will not be included

- 3 denotes a vertex that was included, but was eliminated as it is not necessary

The following images are generated from this source image:

-

The first step takes all pixels that have a non-zero alpha value (or are not explicitely excluded through the ignored colors parameter) and places a 1 in a 2D array. Any pixels that were removed have a value of 0.

-

If the image has extra white space (ie. there is padding on the image), it is cropped out during this step.

-

During this step, any internal pixels that were not previously included are also filled in. For an example of this, see Images/test6.png and Images/test7.png, both of which will produce the exact same set of vertices.

-

-

The next step is to remove the internal pixels of the shape, as only the boundary is needed to detect collisions and draw the object. This is done by checking, for each pixel, if it is surrounded on all sides (including diagonals). If a pixel satisfies this condition, its value is changed to 2.

-

Now that a rough boundary has been acquired, it is time to reduce the number of vertices that provide no information to the final shape. The next group of vertices to be removed are those that are in a straight line, of which we really only need to two endpoints of said line. This is really just checking above and below and left and right of a point and removing the intermediate vertices. Removed vertices are replaced with a 3.

-

During this step, "stair-like" patterns of vertices are reduced to straight lines, reducing the blockiness of the shape.

-

Similar to the step 3, any diagonal straight lines are identified and removed now, there value being replaced with a 3.

The next process is arguably the hardest, and involves adding our vertices in the proper order. This seems like it should be an easy step, just iterate through the array and add any points that have a value of 1, but alas. If we were to do this, the order of our vertices would be incorrect, and shape would zig-zag back and forth, and be a terrible representation of the actual shape. Instead, we have to follow one direction, clockwise or counter-clockwise, consistently, which is easier said than done.

The process begins by starting at (0, 0) and moving horizontally until first pixel marked as a '1' is encountered. Once this value is found, it is added to the list of final points, and the adjacent pixels are checked for either 1s or 3s. The order that the neighbors are checked is very important, and currently something that is being worked on.

Depending on whether or not a 3 or a 1 is found changes the next step slightly. In either case, we will move to that pixel and repeat the process of searching adjacent pixels, but will only add the coordinate to the final vector if the value is a 1.

One of the options that is presented to the user is the level of detail in which to model the texture. There are currently three different levels: Less, More, Optimal. Each of these values represents a percent difference the final polygon is allowed to be from the initial one. No matter the level of detail, the previous conversion is always the same, and this trimming is only done afterwards.

Essentially, we iterate through every points on the shape and find the difference in area if we were to remove it. If we find that the difference is below a certain value, which is based on the level of detail (Less - 10%, More, 3%, Optimal - 1%), we actually remove that point and continue. This allows for us to remove insignificant points systematically. Below are the four levels of detail used to describes Images/test.png, ordered from least to most accurate.

Since our polygon intersection method is based on the lines that surround each shape, one of the most important parts of intersection is to properly be able to address line intersections. The method we use can be seen in (1), but can be summarized as follows: we take ratios of the start and end coordinates of each of the two lines to calculate the percent along each line where they intersect. If these two percents are between 0 and 1, it means that they properly intersect within the domain of both lines, and actually do intersect. This allows to to not only find whether two line segments intersect on their given domain, but also allows us to find the intersection point quite easily. Another benefit of using this method is that if we want to extend a line segment to a full line (which will be useful in finding whether one shape is inside another), we can easily do this by only checking one of the percent values, and ignoring the other.

Before we get to the main intersection method described below, we want to do a simpler test to determine if collision between the two objects is possible. We do this by using SFML's built in FloatRect intersection method, using the absolute bounds of the shape. This means that we use the getGlobalBounds() method for each shape to find whether any of the lines could possibly overlap. This should be taken into account when looking at benchmarks between our total collision method vs. the built in one in SFML, as ours uses the latter.

The main way we detect collisions between two polygons is by taking the vector of lines contained within each polygon class, and iterating through every line with every other line. This may seem to be a rather inefficient method, but since our line intersection method is so simple, the O(n^2) complexity doesn't spiral out of control. Since we also optimize the number of vertices, we rarely have a shape with more than 50 lines, normally we have between 10 and 20. In the future, I would like to optimize this somehow, but as of now, it works and there are more pressing issues to deal with

Not quite sure how to do this just yet, but so far my thoughts are as follows. If we can take the point of intersection for each line (which we can easily find) along with the vertex end of the segment that is inside of the shape (this is the harder part). We can take the vector between these two, as a resultant, and average it with any other resultant vectors, and place them at the average of the vertices found inside the other shape. This is a highly theoretical process and I and have no way to test it as of now, but hopefully a more concrete solution (either this or another one) will stick.