Navigating MIT’s campus, with all the patternless building numbers and semi-infinite hallways, can be difficult and disorienting, especially for those unfamiliar with the area. We built a navigation device optimized for pedestrians to get easy directions around MIT’s central campus. The product’s main components are an ESP32 microcontroller, an MPU9250 inertial measurement unit, an LCD, and a button for input. The user may use the button to click through a series of pages describing their options, like choosing a destination, up to a navigation page where an arrow on the LCD continuously updates to point in the direction of the optimal path, accompanied by an ETA. Invisible to the user, the device makes frequent measurements of nearby WiFi signals, whose strength it uses to determine the device’s location through a Google API, and it also queries a server that stores data on shortest paths around campus and returns the necessary information through the air to the ESP.

Broadly, our navigation device is a handheld computer that guides user’s around MIT’s confusing campus. Our project consists of a server and the ESP device that uses the TFT screen and a button for interfacing, as well as an IMU to both use for destination selection and our navigation compass. The device is connected to a battery and a hotspot, making it a handheld system.

We thought this problem would be interesting to solve both because of its usefulness to MIT students and the knowledge we learned in 6.08 that we felt we could apply. The only existing internal navigation system between MIT buildings is manually reading the map on Atlas. We initially thought of creating a mapping device similar to the one on the Apple watch. We wanted the user to know when to turn and just be able to look down at the device and follow its directions without having to have any knowledge about the inner workings of MIT’s complex building layout. We feel that this problem is interesting and applicable, and we faced many technical challenges when solving it. We were motivated by the idea that our device could actually be useful to us and other individuals accessing MIT’s campus on a daily basis.

We developed our Tiny Tim navigation device with the typical first-time-visiting pre-frosh in mind, so it is fully equipped to provide simple directions to any of the main academic buildings. To use, the user first inputs a destination by scrolling through a list of buildings by tilting, selecting one with a short button push, and choosing the floor they want to be guided to. After selecting the destination, the screen displays a few pieces of information: the final destination, the current building location, the ETA in seconds, and finally a big arrow that points in the correct direction of their navigation route. At any point during a route, it can be canceled by a long push of the button. When a user arrives at their desired destination, a message telling the user they have arrived appears.

Our system consists of two primary components: our server and the ESP32 microcontroller. The server is responsible for heavy computation such as shortest path, graph construction, caching, and formatting the response. The ESP32, on the other hand, is the user's interface for our system. It is through the ESP32 that the user can enter their destination and follow the instructions to receive navigation instructions. The goal of our system was to abstract most of the complex functionality and allow the user to interface with our entire system through only an LCD and a single button.

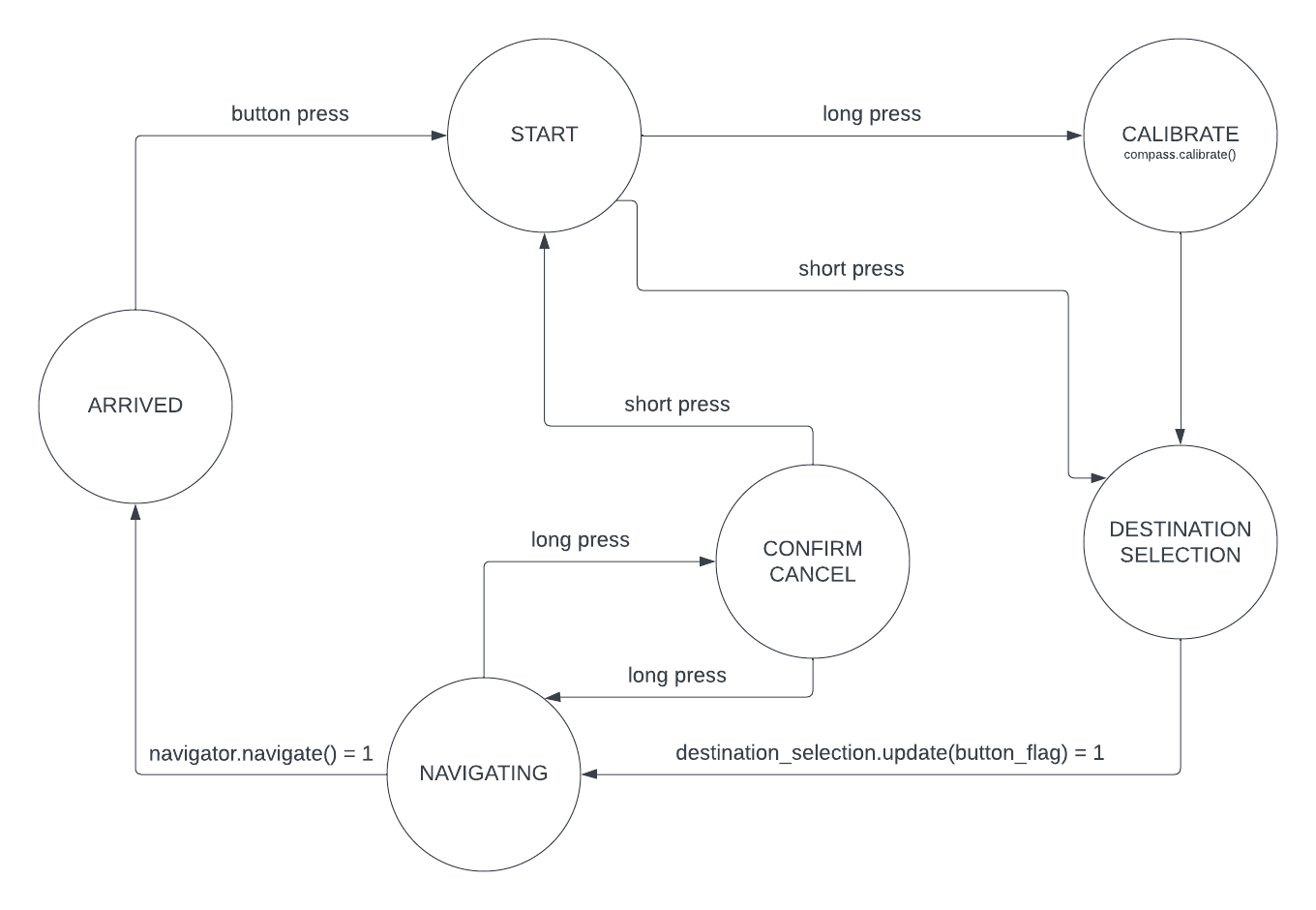

This is the main state machine of our system. As seen above, the 6 states the user can enter are: START, CALIBRATE, DESTINATION_SELECTION, NAVIGATING, ARRIVED, and CONFIRM_CANCEL.

START: This is the state when the device is first turned on. There is very little actually happening except for an introductory screen with instructions being displayed.

CALIBRATE: When this state is entered, compass.calibrate() is called, which begins a 30-second period of compass calibration.

DESTINATION_SELECTION: When this state is entered, destination_selection_flag = destination_selection.update(button_flag). The functionality of selecting a destination is abstracted by our DestinationSelection component. When the destination_selection_flag == 1, the user has selected their destination, and we can transition states.

NAVIGATION: When this state is entered, navigation_flag = navigator.navigate(). The details of navigation (i.e. locating, routing, and displaying compass) are abstracted by our Navigation component. When the navigation_flag == 1, the user has arrived and we can transition states.

ARRIVED: This state is fairly simple. A message is displayed to the user letting them know they have arrived at their destination. From here, a user can restart and navigate to a new destination.

CONFIRM_CANCEL: This state is fairly simple. If at any point, a user wants to end their navigation prematurely, they will enter into this state, where they will have the option to resume navigation or confirm their decision to cancel and start again.

The ApiClient is the component within our system that allows our ESP32 to directly communicate with both Google’s API for retrieving current latitude and longitude and also our team’s server. Once we receive a response from Google’s API or our team’s server, we are able to parse the response by utilizing an implementation we created in a lab earlier in the class. Also, our ApiClient makes sure that we are connected to a WiFi network before any requests are sent out to ensure our requests have a network to be sent over.

We optimized our system for the walking commuter by including a continuously updated arrow that displays on the screen and tells the user which way to walk. No more Google Maps thinking you’re holding your iPhone upside down and suddenly turning around after you’ve walked forty meters in the wrong direction. An onboard IMU, equipped with a magnetometer, gyroscope, and accelerometer calibrated to calculate rotation relative to true North, provides the user the directions they need relative to where they’re facing as soon as they select a destination and guides them the whole way there.

There are a number of steps involved in the calculation of the angle of the arrow displayed on the LCD. The compass measures an offset angle from North. If we display arrow with the negative of this angle, and we adjust by the relative rotation of the axes of the IMU and LCD, then we already have a compass that points North. Since the server sends the direction to the next node as an angle offset from East using the math.arctan2() function, we must adjust our North-facing compass first by 90 degrees, and then by the angle dir_next_node from the server. Getting negative signs right and ensuring proper units was challenging.

We have hopes for the Tiny Tim to eventually be made smaller and even into a watch so for inputting a destination, we wanted a simple, but accurate method. This component abstracts the functionality of tilting to scroll and clicking the button to select. With tilting and just one button the device could be made very small.

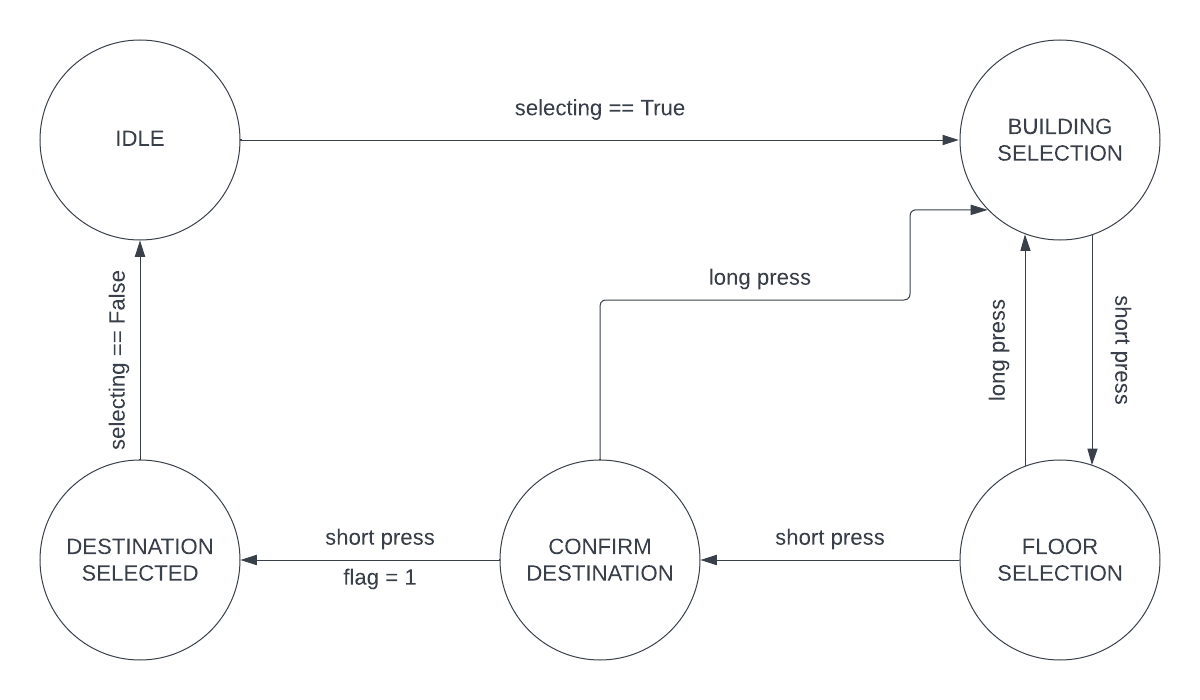

The Destination Selection component has 5 states: IDLE: BUILDING_SELECTION, CONFIRM_DESTINATION, and DESTINATION_SELECTED.

IDLE: This is the default state for the destination selection. In this state, there is nothing happening. Only once the user begins their destination selection do they transition out of this state and into BUILDING_SELECTION

BUILDING_SELECTION: It is in this state that the user is able to tilt to scroll through the building selection choices. Once they have arrived at their desired choice, they can click the button to confirm it and transition into floor selection. A long clear also clears the selection

FLOOR_SELECTION: It is in this state that the user selects their destination floor. Like the previous state, the user can tilt to scroll, and once they have chosen their destination floor, they can click the button to select. A long press also clears their current selection and brings them back to BUILDING_SELECTION. In this

CONFIRM_DESTINATION: This is a similar state to the confirm_ state we saw in the main state machine. This allows the user to confirm their destination selection or clear their current selection and try again. Once the user confirms, flag = 1, representing a selection has been made.

DESTINATION_SELECTED: This is a very simple state. In this state, the user has already selected their destination and so an external component can call destination_selection.get_destination_building(destination_building) and destination_selection.get_destination_floor(destination_floor) to get the current selection. Once the selection is finished, this component transitions back to IDLE.

The navigation display was designed to correctly instruct, but not overwhelm the user. We wanted to fix the issue where in google maps, the starting direction of your arrow during a route often points in the wrong direction. We decided that a compass was necessary to provide clear direction for users to follow, as well as other important pieces of info to help users along the way. For example, the current building is displayed so a user can familiarize themselves with campus.

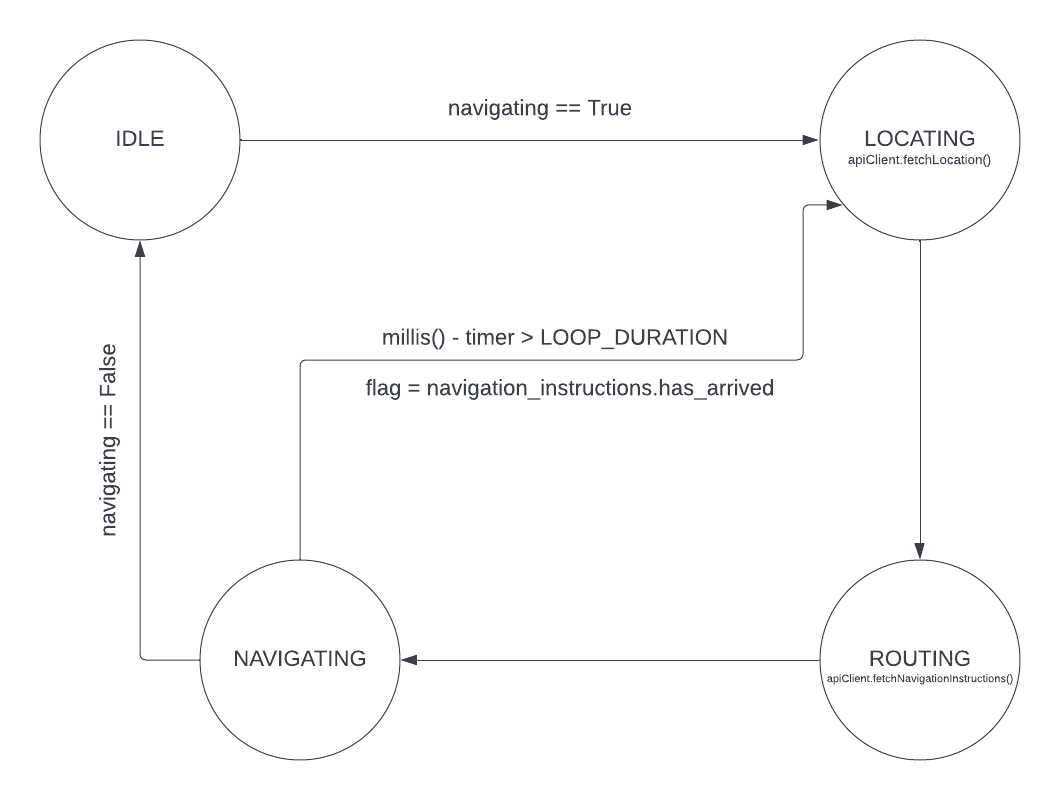

The navigation component exposes a single function navigation.navigate() and has 4 states: IDLE, LOCATING, ROUTING, NAVIGATING.

IDLE: This is a very simple state. In this state, the component does nothing. Only once the navigation begins does the transition out of this state occur.

LOCATING: This state is responsible for using the ApiClient to query Google's geolocation api to get the current location. This lat, lon pair can then be used in conjunction with a destination to query our server for a shortest path.

ROUTING: This state is responsible for making a request to our server using the coordinates received in the previous state. Once the instructions are received, a transition to NAVIGATING occurs.

NAVIGATING: This state continually updates the compass to make sure that the arrow is pointing in the direction instructed by the server. Additionally, once LOOP_DURATION elapses, a transition to LOCATING occurs and the cycle continues. If the user has arrived at their location, flag = 1, which signals to the consumer of this component that the user has arrived at their destination. If navigating = False because navigation.end_navigation() was called, then the next state transitioned to is START. This is because this would mean that the navigation is over so that the Navigation component should no longer make requests to Google or our server.

With the tests of our system on the ESP32, we wanted to make sure all the different components were able to run correctly independent from one another. Thus, we created separate folders to test each of the components: ApiClient, Navigation, Compass, and Destination Selection. For ApiClient, we made sure to test that we were able to create a reliable WiFi connection, consistently were able to send requests to Google’s API and our server (and receive a response), and also correctly parse responses.

For Navigation, we hard coded a current node as well as a destination node from our graph and had the “navigator” request the shortest path from our server to tell the user the next node that they need to go to. The “navigate” function within the Navigation class has its own state machine which keeps track of which part of the process of navigating the user is in (IDLE, LOCATING, ROUTING, NAVIGATING). Basically, our test runs through navigating the initial node from the starting location, but we print out the response from our server to make sure it is correct.

For Compass, we took the one compass class and built an isolated arduino script for it that calls and verifies each public method of the compass class (including the calibration, refresh data, calculate quaternion, angle of return, update display, and initialization). Some of our bigger bugs were not calling refresh data and calc quaternion every time through the loop, and we were 1 indexing instead of 0 indexing in a small nearly invisible variable.

For Destination Selection, we put the destination selection into its own class, added getter methods for the destination string and destination_floor string. We made sure that we were able to select a building and floor from a list of hard-coded buildings that were mapped already on our server side.

@unique

class NodeType(str, Enum):

BUILDING = "b"

ELEVATOR = "e"

STAIR = "s"

@dataclass

class Node:

id: str

location: Location

building: str

floor: int

node_type: Optional[NodeType] = NodeType.BUILDING

@dataclass

class Edge:

v1: Node

v2: Node

weight: float = field(init=False)

direction: Optional[float] = field(init=False)

class Graph:

def __init__(self):

self._vertices: Dict[str, Node] = dict() # node_id -> node

self.buildings: Dict[str, Set[str]] = dict() # building -> node_id

self.floors: Dict[int, Set[str]] = dict() # floor -> node_id

self.types: Dict[NodeType, Set[str]] = dict() # NodeType -> node_id

self.adj: Dict[str, Dict[str, float]] = dict() # adj matrix with weights {node_id: {node_id: weight}}

class Polygon:

def __init__(self, vertices: Optional[List[Location]] = None):

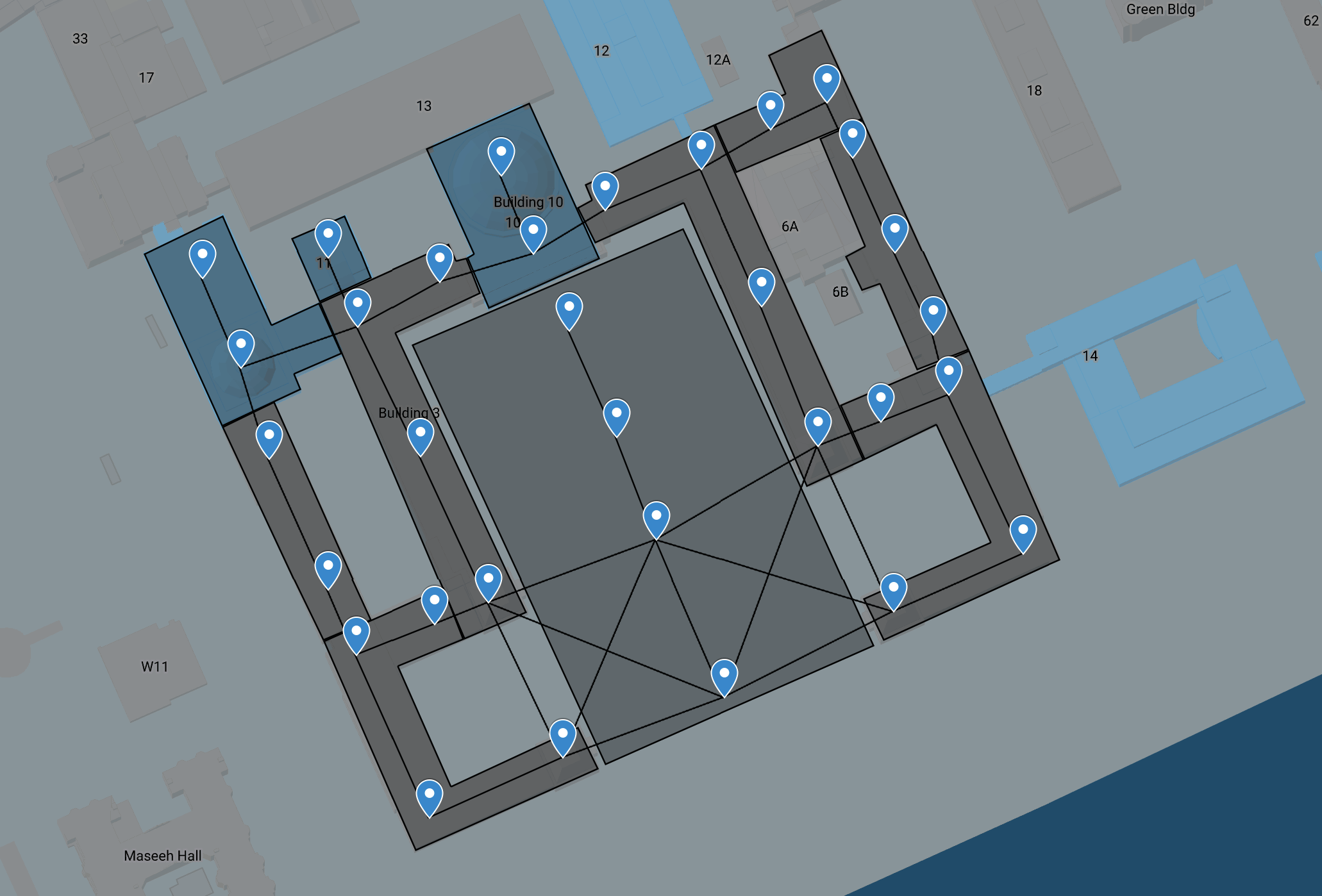

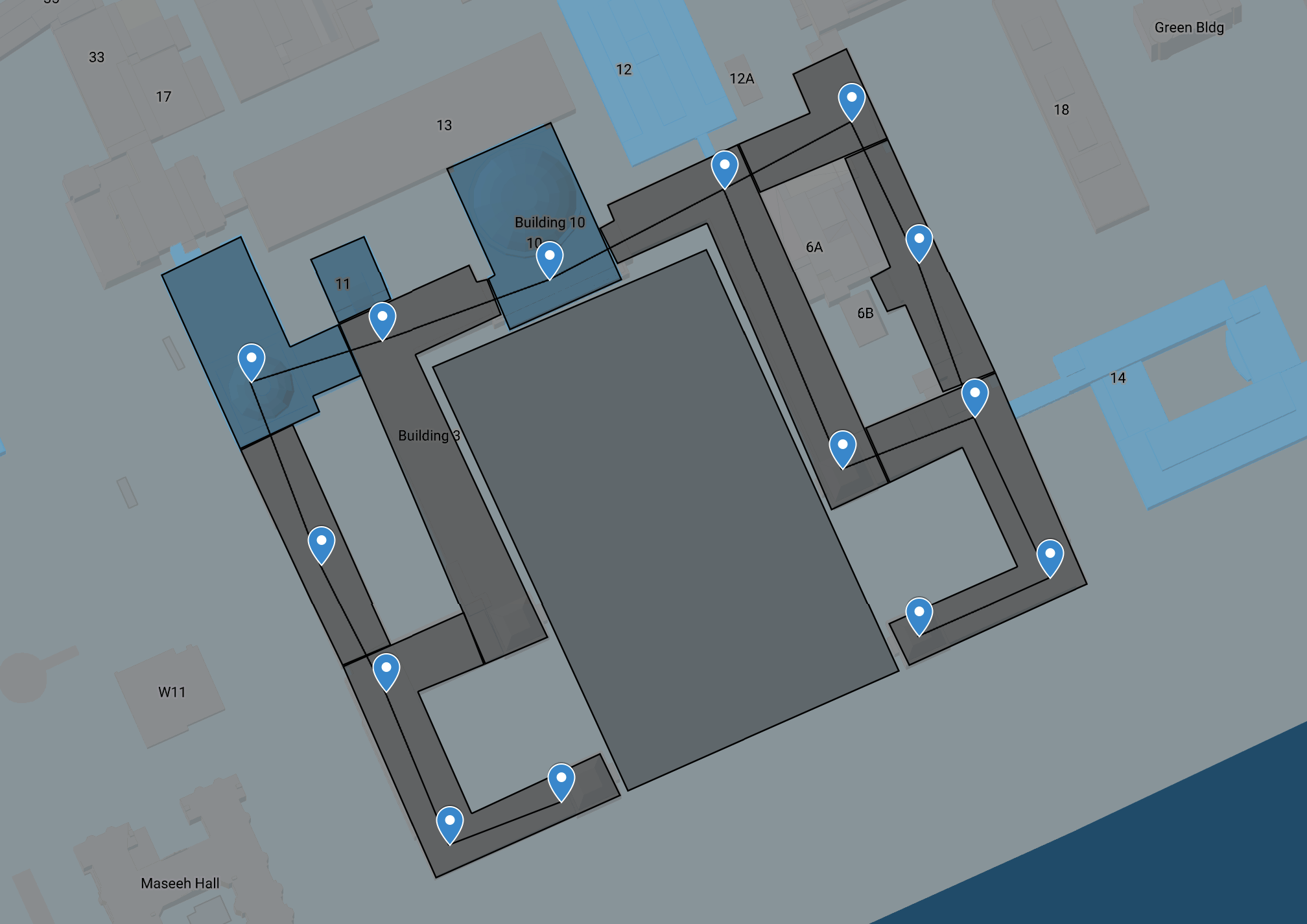

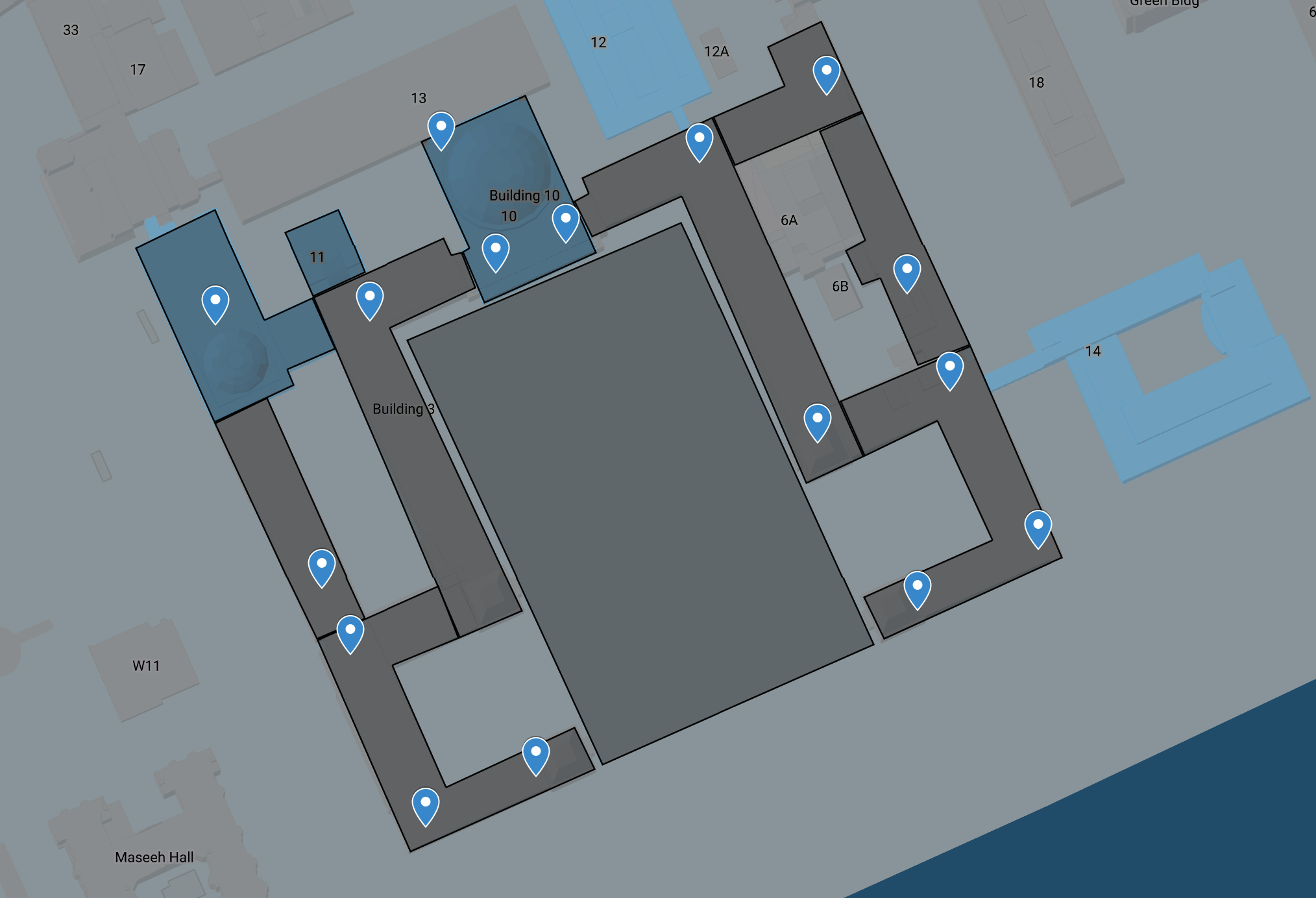

self.vertices = [] if vertices is None else verticesOur graph is the main component of our server, and it represents the network of MIT buildings we support on our system. Using google maps, we dropped pins at strategic locations (1+ per building) and connected them based on our knowledge of valid footpaths. This network of nodes and edges makes up our graph. Additionally, each building is represented as a Polygon object which is essentially a list of adjacent points of a building, where each point is a coordinate. This can also be seen in the image below:

To construct our graph, we download the csv files from our graph representation of MIT buildings stored on google maps. Then, our system parses these three files and creates our graph representation. This is done by the following methods:

def parse_polygons(polygons_csv_file_path: str) -> Dict[str, Polygon]:

"""

Returns dictionary mapping building name to polygon representation of building

CSV structure is assumed to be <Polygon str>, <building num>, <description>

"""

pass

def parse_nodes(nodes_csv_file_path: str, polygons: Dict[str, Polygon], floor: Optional[int], node_type: NodeType = NodeType.BUILDING) -> List[Node]:

"""

CSV structure is assumed to be <location str>, <building num>, <description>

"""

pass

def parse_edges(edges_csv_file_path: str, nodes: List[Node]) -> List[Tuple[str, str]]:

"""

Returns list of pairs of node ids representing edges to be added to our graph.

CSV structure is assumed to be <Edge str>, <edge name>, <description>

"""

pass

def create_graph(nodes: List[Node], edges: List[Tuple[str, str]], num_floors: int) -> Graph:

"""

Takes in a list of nodes and list of edges and creates a graph representation of them.

"""

passTo make our graph construction scalable (i.e. make it easy to add new floors + nodes), we standardized our node Naming Schema: <unique_id>_<node_type>. The unique id refers to a unique identifier within the floor of a specific building. In other words, the triple (building_num, floor, unique_id) will always be globally unique.

In order to support multiple floors on our graph, we standardized the naming schema of node and edge files. Originally, our system simply took in 3 files: nodes.csv, edges.csv, and polygons.csv. However, with the addition of multiple floors, we expanded our system to expect a more inclusive file naming system. For our current system, files must be named nodes_<floor_number>.csv and edges_<floor_number>.csv. Additionally, our system takes in two other files: stairs.csv and elevators.csv that represent the connection between floors. To support these changes, we expanded our system to support 3 different node types:

- Building nodes (b)

- Elevator nodes (e)

- Stair nodes (s)

Building nodes are handled differently to elevator nodes and stair nodes. To add stair/elevator to our graph, we did the following:

- For each stair/elevator node, we create a new node (v) for each floor we support. Then, for each node v on each floor, we added an edge to the closest building node on that floor and automatically weighted it. Finally, we add “vertical” edges between each node v on different floors corresponding to the original stair / elevator. This edge was given a default weight of 20 to represent ascending or descending stairs / elevators.

This graph modification allows us to easily add shortest path constraints in the future, and also allows us to continue to use Dijkstra’s (as opposed to having to create a new shortest path algorithm) to find the shortest path between nodes on different floors.

@dataclass

class Route:

source: str

destination: str

path: List[str]

distance: float

class Graph:

def get_closest_node(self, point: Location, floor: int = 1, node_type: NodeType = NodeType.BUILDING) -> str:

"""

Given location, find the closest building node in the graph on the same floor. This will be used to as the start

node when calculating the shortest path from a location

"""

pass

def sssp(self, src: str):

"""

Solves sssp from src node on our path.

src is a valid node id and graph is a valid graph representation

Returns distance dictionary with shortest distance to every node and parent point dictionary

"""

pass

@staticmethod

def parse_sssp_parent(parent: Dict[str, str], dest: str):

"""

Takes in parent pointer dictionary (result of single source shortest path algorithm) and returns a list of

node ids represent the shortest path to destination.

"""

pass

def find_shortest_path(self, src: str, building_name: str, floor: int = 1, use_cache: bool = True) -> Route:

"""

Takes in a source node, a destination building and floor, and returns a route which represents the shortest path

from the source to the destination. This process involves running Djikstra's to solve sssp and then parsing the

parent pointer to get a chain of nodes as the shortest path.

"""

pass

def apsp(self):

"""

For every valid source node (i.e. building nodes), destination building, and destination floor combination,

this runs self.find_shortest_path() and returns a mapping (src, building, floor) -> Route. This will allow

us to easily cache the shortest path in the future (instead of having to run it on every request).

"""Once we were able to represent the network of MIT buildings as a graph of Nodes and Edges, finding the shortest path between a source and a destination building / floor pair was not very difficult. This process involved:

- Finding the closest node to a location / current floor and setting it as the source node

- Implementing Djikstra's to solve single source shortest path for that source node

- Parsing the parent node (i.e. tracing it back) for a src, dest_building, dest_node to get a chain of nodes representing the shortest path. This was done by iterating through every node on the destination floor of the destination building and finding the node with the minimum shortest path distance to the source node. Once we had a source node and a destination node (as opposed to a destination building and floor), we could trace the parent pointer returned by sssp to get the actual chain of nodes from a source to a destination. This chain of nodes represents the shortest path from a source node to the closest node on the right floor of the destination building.

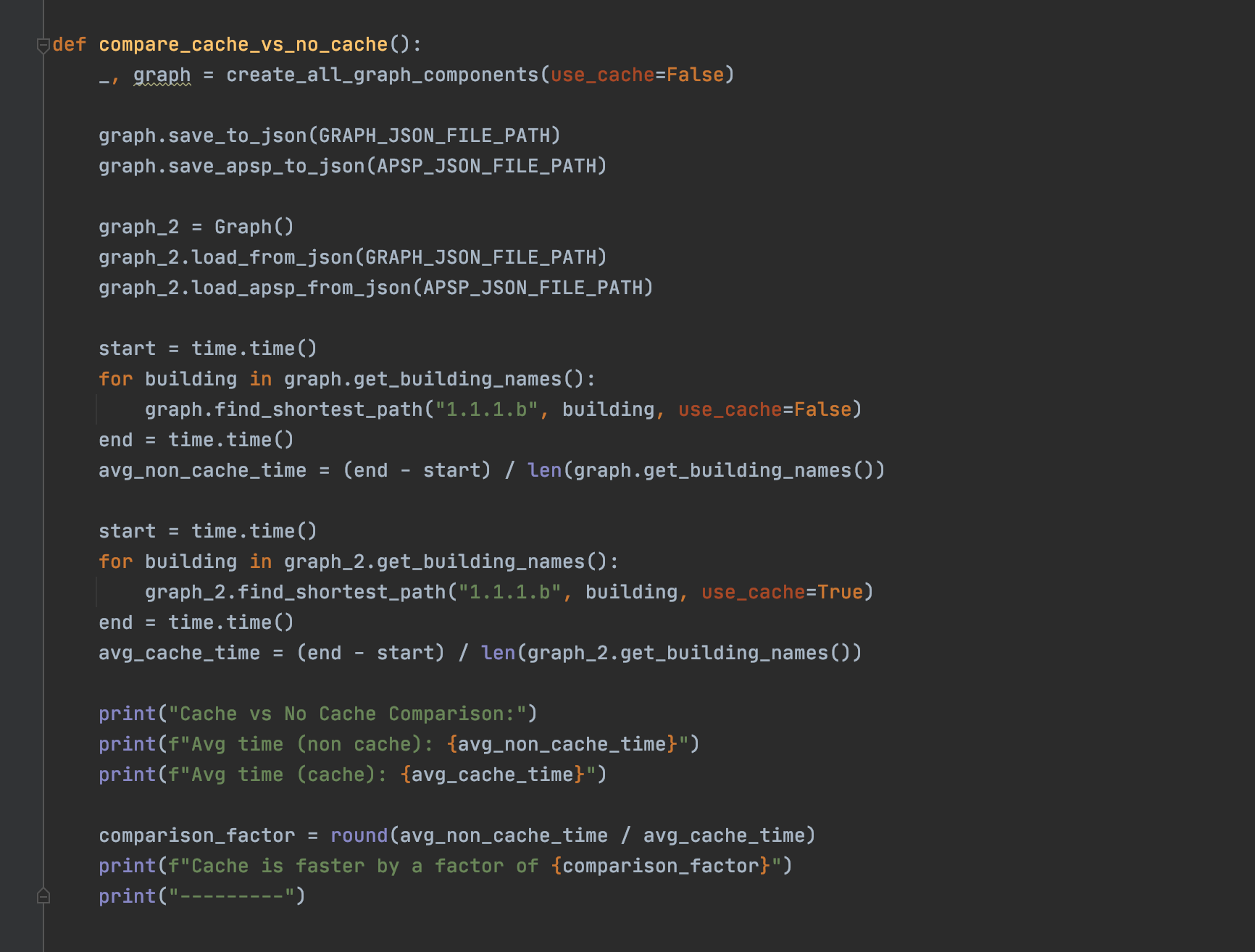

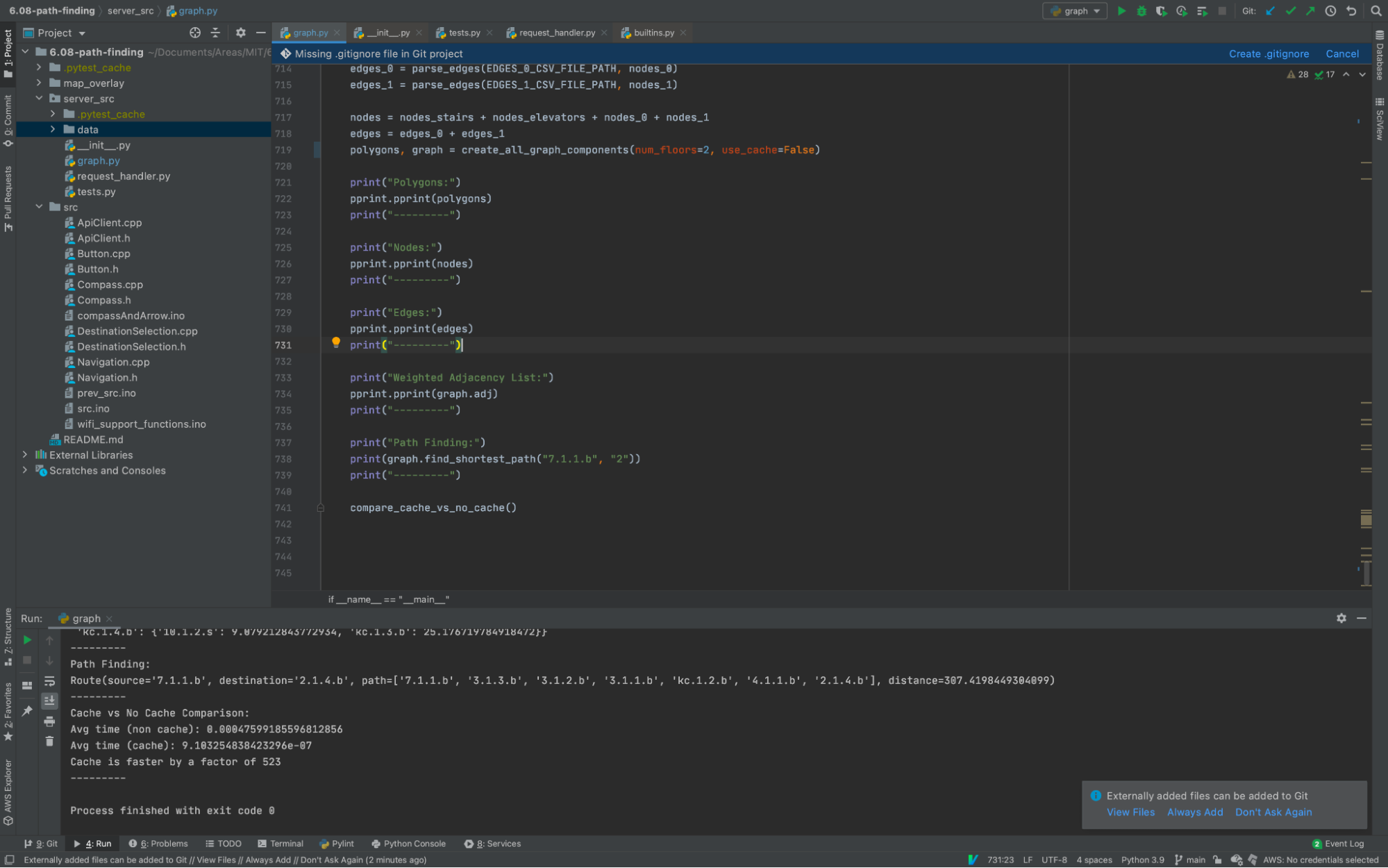

All pairs shortest path simply implements the process mentioned above in order to compile a shortest path for every possible (source, building, floor) combination. This allowed us to cache that mapping in a file (apsp.json) and very efficiently find the shortest path (i.e. looking a value up in a dictionary is O(1) as opposed to O(|V| + |E|) for running sssp on every request).

There were two major optimizations we implemented server-side: Caching our graph representation as a json file and caching the results of all pairs shortest path as discussed above.

class Graph:

def load_from_json(self, json_file_path: str):

"""

Loads graph representation to json file.

{

node_id: {

'node': Node,

'adj': {n1_id: dist, n2_id: dist, ..., ni_id: dist}

},

}

"""

pass

def save_to_json(self, json_file_path: str):

"""

Dumps graph representation to json file.

{

node_id: {

'node': Node,

'adj': {n1_id: dist, n2_id: dist, ..., ni_id: dist}

},

}

"""

passThis optimization allowed us to very efficiently recreate our graph on every request without having to parse 6+ different files. Instead, we can very easily load the json file as a python dictionary and iterate over each entry to create our graph.

class Graph:

def load_apsp_from_json(self, json_file_path: str):

pass

def save_apsp_to_json(self, json_file_path: str):

passThis optimization allowed us to very efficiently find the shortest path based on a user's request. This is because instead of solving sssp and parsing the parent pointers on every request, we can very easily load apsp.json as a python dictionary and look up (src, building, floor) to find the shortest path.

@dataclass

class RequestValues:

user_id: str

point: graph_utils.Location

destination: str

current_floor: int

destination_floor: int

@dataclass

class Response:

curr_building: str

next_building: str

curr_node: str

next_node: str

dist_next_node: float

dir_next_node: float # degrees counterclockwise offset from east

has_arrived: bool

eta: str

dest_node: str

dest_building: int

def request_handler(request):

if request['method'] != "GET":

return f"{request['method']} requests not allowed."

try:

request_values = try_parse_get_request(request)

except AssertionError as e:

return e

except ValueError:

return "Both lat and lon must be valid coordinates"

polygons, graph = graph_utils.create_all_graph_components(use_cache=True)

curr_node = graph.get_node(graph.get_closest_node(request_values.point, floor=request_values.current_floor))

curr_building = graph_utils.get_current_building(polygons, request_values.point)

has_arrived = (curr_building == request_values.destination and

request_values.current_floor == request_values.destination_floor) or \

(curr_node.building == request_values.destination and

curr_node.floor == request_values.destination_floor)

route = graph.find_shortest_path(curr_node.id, request_values.destination, request_values.destination_floor)

next_node = graph.get_node(route.path[1]) if len(route.path) > 1 else curr_node

dest_node = graph.get_node(route.destination)

dist_next_node = graph_utils.calculate_distance(curr_node.location, next_node.location)

dir_next_node = graph_utils.calculate_direction(curr_node.location, next_node.location)

eta = graph_utils.calculate_eta(route.distance)

response = Response(curr_building=curr_node.building, next_building=next_node.building,

curr_node=curr_node.id, next_node=next_node.id,

dist_next_node=dist_next_node, dir_next_node=dir_next_node,

has_arrived=has_arrived, eta=eta, dest_node=dest_node.id, dest_building=dest_node.building)

response_dict = asdict(response)

response_dict["has_arrived"] = int(response.has_arrived)

return json.dumps(response_dict)Our request handler was fairly straightforward. It involved creating our graph, finding the closest node, looking up the shortest path in our apsp_cache, and calculating any additional fields we want to return as part of our response.

We tested the server side and client side separately before integrating all of our components.

We have several unit test classes on the server side for the Python code.

- Polygon Tests: Test the parsing of polygons from polygons csv to polygon objects.

- Node Tests: Test the parsing of nodes with and without a polygon csv.

- Edge Tests: Tests that all edges are unique.

- Graph Tests: Tests the saving and loading of a graph to and from a json. Also tests the caching of the results of the all pairs shortest path algorithm.

- Closest Node Tests: Tests whether the closest node is correctly returned given a location in a building.

- Current Building Tests: Tests for each building manually whether a location returns the correct building.

- Dijkstra Tests: Tests that Dijkstra’s returns the correct shortest path.

- ESP32

- TFT LCD

- MPU9250 IMU

- button

- micro USB battery pack

This project was heavier on code and lighter on hardware, and most of our issues came from code not working. Errors ranged from the simple common inevitable errors, like indexing incorrectly and , to more formidable systematic problems that took weeks to solve. Here were some of our bigger roadblocks, and how we got around them.

-

WiFi issues Not staying connected to WiFi when moving around campus was an issue. We had problems connecting the ESP32 to an iPhone hotspot but eventually sorted that out. Thus, we were able to sustain a pretty reliable network connection while moving around on campus so that we could send http requests.

-

Compass The compass didn’t point in the correct direction at first, but after digging into the code for how we calibrated the compass, we were able to get it pointing in the right direction (for a certain radian input, it was able to point an arrow a relative offset from East).

-

Request handler performance The request handler had an issue when we would have the ESP32 connected to an iPhone hotspot. With certain iPhone hotspots, the team server request would respond with a 502 bad gateway error for some reason. Fortunately, the request would work consistently when connected to a particular teammate’s iPhone hotspot.

-

Calculating the direction for the compass to point too: There were lots of bugs with the formula to calculate the heading counterclockwise from east in radians. We also had to make sure that the calculation on our server side to get direction between nodes could be translated to what was needed on the ESP. After doing some rigorous analysis of the formulas we use, we were able to create a system which allowed the lcd display to show an arrow pointing in the direction which the user needs to walk.

-

Google downloaded data flipping lat and lon We mistakenly thought that Google’s API sent its latitude and longitude response in a particular order, but realized it was flipped. This was an easy fix as we simply needed to switch the variables we were setting after parsing the Google API response.

The src file contains the central state machine of the project as well as the setup() and loop() functions for the whole script. First we initiate instances of the following classes: Button, TFT_eSPI, ApiClient, Compass, Navigation, and DestinationSelection. We will use these class objects to call specific public functions we have organized in the respective cpp files. We also create an enum with the names of our global states. In the START state, we welcome our user and prompt them to press the button to either activate the guide or calibrate the compass. In the CALIBRATE state we call compass.calibrate(), a function described below. In the DESTINATION_SELECTION state we choose the building and room we want to travel to. In the NAVIGATING state, we display where and how far the destination is with an arrow and an ETA. We stay here until the user either arrives at the destination, moving us to the arrived state, or the user long presses to cancel the current navigation and moves to the Confirm Cancel Navigation state. In the CONFIRM_CANCEL state, we stay until either a short press confirms that we are canceling the navigation and we move to Start state, or a long press cancels the navigation cancel and we return to the previous route. In the ARRIVED state, we will display an arrival message until a short press moves us back to the Start state. The setup() function initializes the LCD and compass and displays the welcome message. The loop() function calls the only four functions which must be continuously called, those relating to measurements and paging through the state machine. These are

compass.refresh_data(); compass.calc_quaternion(); int button_flag = button.update(); global_update(button_flag);

One of our big goals with src was to be the epicenter of a modularized body of code for easy understanding and for distributing and isolating sources of error for easy debugging.

struct Vec {

float x;

float y;

};

struct RGB { //looks like this won't actually be used since tft.stroke(r,g,b) isn't a real function I can use

int r;

int g;

int b;

};

// ----- Set initial input parameters

enum Ascale {

AFS_2G = 0,

AFS_4G,

AFS_8G,

AFS_16G

};

enum Gscale {

GFS_250DPS = 0,

GFS_500DPS,

GFS_1000DPS,

GFS_2000DPS

};

enum Mscale {

MFS_14BITS = 0, // 0.6 mG per LSB;

MFS_16BITS // 0.15 mG per LSB

};

enum M_MODE {

M_8HZ = 0x02, // 8 Hz ODR (output data rate) update

M_100HZ = 0x06 // 100 Hz continuous magnetometer

};

class Compass {

private:

TFT_eSPI* tft;

Vec center; // for display

Vec p1, p2, p3, p4, p5, p6, p7; // the points that define the arrow

float device_angle; //for storing the angle sensed by magnetometer

int center_y; // only y center should change We don't need to fit that much on the screen

float Mag_x_offset, Mag_y_offset, Mag_z_offset, Mag_x_scale, Mag_y_scale, Mag_z_scale;

RGB color;

int length; // based on where we want to center the arrow we should be able to scale its length so it doesn't go off the screen.

int width;

int left_limit; //left side of screen limit

int right_limit; //right side of screen limit

int top_limit; //top of screen limit

int bottom_limit; //bottom of screen limit

// ----- Magnetic declination

/*

The magnetic declination for Lower Hutt, New Zealand is +22.5833 degrees

Obtain your magnetic declination from http://www.magnetic-declination.com/

By convention, declination is positive when magnetic north

is east of true north, and negative when it is to the west.

Substitute your magnetic declination for the "Declination" shown below.

*/

float Declination;

char InputChar;

bool LinkEstablished;

String OutputString;

unsigned long Timer1;

unsigned long Stop1;

// ----- Specify sensor full scale

byte Gscale;

byte Ascale;

byte Mscale; // Choose either 14-bit or 16-bit magnetometer resolution (AK8963=14-bits)

byte Mmode; // 2 for 8 Hz, 6 for 100 Hz continuous magnetometer data read

float aRes, gRes, mRes; // scale resolutions per LSB for the sensor

short accelCount[3]; // Stores the 16-bit signed accelerometer sensor output

short gyroCount[3]; // Stores the 16-bit signed gyro sensor output

short magCount[3]; // Stores the 16-bit signed magnetometer sensor output

float magCalibration[3], magBias[3], magScale[3]; // Factory mag calibration, mag offset , mag scale-factor

float gyroBias[3], accelBias[3]; // Bias corrections for gyro and accelerometer

short tempCount; // temperature raw count output

float temperature; // Stores the real internal chip temperature in degrees Celsius

float SelfTest[6]; // holds results of gyro and accelerometer self test

// ----- global constants for 9 DoF fusion and AHRS (Attitude and Heading Reference System)

float GyroMeasError; // gyroscope measurement error in rads/s (start at 40 deg/s)

float GyroMeasDrift; // gyroscope measurement drift in rad/s/s (start at 0.0 deg/s/s)

unsigned long delt_t; // used to control display output rate

unsigned long count, sumCount; // used to control display output rate

float pitch, roll, yaw;

float deltat, sum; // integration interval for both filter schemes

unsigned long lastUpdate, firstUpdate; // used to calculate integration interval

unsigned long Now; // used to calculate integration interval

float ax, ay, az, gx, gy, gz, mx, my, mz; // variables to hold latest sensor data values

float q[4]; // vector to hold quaternion

float eInt[3]; // vector to hold integral error for Mahony method

void getMres();

void getGres();

void getAres();

void readAccelData(short* destination);

void readGyroData(short* destination);

void readMagData(short* destination);

short readTempData();

void initAK8963(float* destination);

void initMPU9250();

void calibrateMPU9250(float* dest1, float* dest2);

void magCalMPU9250(float* bias_dest, float* scale_dest);

void MPU9250SelfTest(float* destination);

void writeByte(byte address, byte subAddress, byte data);

byte readByte(byte address, byte subAddress);

void readBytes(byte address, byte subAddress, byte count, byte* dest);

void MahonyQuaternionUpdate(float ax, float ay, float az, float gx, float gy, float gz, float mx, float my, float mz);

int angle_return();

public:

Compass(TFT_eSPI* _tft, int center_y);

void update_display(float dir_next_node);

void initialize();

void refresh_data();

void calc_quaternion();

void calibrate();

float get_ay();

};

A compass object is initialized in src and has access to the following public functions:

This includes all the functions and setup for waking up the IMU and ensuring it is functioning/has the necessary parameters.

This function is called when the user wishes to calibrate their IMU for their specific hardware setup. It tells the user to tumble the compass in figure 8 patterns for 30 seconds so that the internal calibration methods can collect data and generate new calibration parameters, which are automatically updated.

This function measures the gyroscope, accelerometer, and magnetometer with the IMU

Using the new values from refresh_data we can compute the quaternion that represents our most accurate estimate of the actual rotation in space of the device.

This is the function called once every loop period in the navigation_display state. It calls an internal function angle_return which makes use of the updated quaternions to figure out the heading of the compass. This value, which is an angle offset from east, is used to determine what corrective angle should be applied to the arrow for it to point in the direction of the optimal path. Using this angle and the Adafruit_GFX.h library we construct the graphics that build the arrow and display them.

Behind the scenes the compass code is mostly ensuring everything is set up and measured and updated and scaled and offset correctly, including using the Mahony quaternion update sensor fusion algorithm which converts IMU measurements into a quaternion representing rotation.

const uint16_t IN_BUFFER_SIZE = 5000; // size of buffer to hold HTTP request

const uint16_t OUT_BUFFER_SIZE = 5000; // size of buffer to hold HTTP response

const uint16_t JSON_BODY_SIZE = 5000;

class ApiClient {

static const uint16_t RESPONSE_TIMEOUT;

static char GOOGLE_SERVER[];

static char TEAM_SERVER[];

static const char GEOLOCATION_REQUEST_PREFIX[];

static const char GEOLOCATION_REQUEST_SUFFIX[];

static const char GEOLOCATION_API_KEY[];

static const int MAX_APS;

static const char CA_CERT[];

static char network[];

static char password[];

static uint8_t scanning;

static uint8_t channel;

static byte bssid[];

WiFiClientSecure client; // global WiFiClient Secure object

WiFiClient client2; // global WiFiClient Secure object

static char request[IN_BUFFER_SIZE];

static char response[OUT_BUFFER_SIZE]; // char array buffer to hold HTTP request

static char json_body[JSON_BODY_SIZE];

static int max_aps;

static int offset;

static int len;

uint8_t char_append(char *buff, char c, uint16_t buff_size);

public:

ApiClient();

void initialize_wifi_connection();

void do_http_request(char *host, char *request, char *response, uint16_t response_size, uint16_t response_timeout, uint8_t serial);

void do_https_request(char *host, char *request, char *response, uint16_t response_size, uint16_t response_timeout, uint8_t serial);

int wifi_object_builder(char *object_string, uint32_t os_len, uint8_t channel, int signal_strength, uint8_t *mac_address);

StaticJsonDocument<500> fetch_location();

StaticJsonDocument<500> fetch_navigation_instructions(char* user_id, double lat, double lon, int current_floor,

char* destination, int destination_floor);

};

An ApiClient object is initialized in our src file and utilized to make requests to Google’s API and our team’s server. ApiClient.h defines the variables and functions that were implemented in ApiClient.cpp:

This function is what is used to make a connection to WiFi. It utilizes the WiFiClient.h library to loop through the BSSIDs that are near the ESP32 and then connects to a given hardcoded network stored in the network variable (by using a hardcoded password stored in the password variable).

This function takes in a pointer to character array (buff) which we will append char c And buff_size is how the size of the buffer is defined. True is returned if the character was appended successfully and False if it was not appended because the buffer was full.

Both of these functions were directly copied from a previous lab in 6.08 and is what is used to format and send our http and https requests to our team’s server and Google’s Api respectively.

This is another function from another earlier lab in 6.08 which generates a json-compatible entry for use with Google's geolocation API.

At the beginning of this function, we utilize the WiFiClient.h library again to scan for nearby networks to pass to Google’s Api (so that we get an accurate estimate of the ESP32’s location). After completing this, we build an https request using a request buffer (variable request). Once we receive the response by utilizing our do_https_request function, we parse the response and create a Json object for the response so that we can easily select values we need from the response.

fetch_navigation_instructions(char* user_id, double lat, double lon, int current_floor, char* destination,int destination_floor);

This function takes in a user_id for the current user, their latitude and longitude that we received from Google’s Api (stored in lat and lon variables), the current_floor that they are on and the destination building (destination variable) and destination_floor which is received from Destination Selection. With these parameters, we use a request buffer to build a request to send to our team’s server. The server then returns relevant information about the user’s current journey and we parse this response and store it in a JSON format similar to fetch_location.

enum destination_selection_state {IDLE, BUILDING_SELECTION, FLOOR_SELECTION, CONFIRM_DESTINATION, DESTINATION_SELECTED};

class DestinationSelection {

static const char BUILDINGS[NUM_BUILDINGS][5];

static const char FLOORS[NUM_FLOORS][5];

static const int SCROLL_THRESHOLD;

static const float ANGLE_THRESHOLD;

destination_selection_state state;

int destination_building_index;

int destination_floor_index;

uint32_t scroll_timer;

TFT_eSPI* tft;

MPU6050 imu;

Compass* compass;

bool selecting;

void get_angle(float* angle);

void clear_selection();

void display_selection();

public:

DestinationSelection(TFT_eSPI* _tft, Compass* _compass);

void initialize_imu();

void begin_selection();

void end_selection();

void get_destination_building(char* building);

void get_destination_floor(char* floor);

int update(int button_flag);

};

A DestinationSelection obj is initialized with pointers to the tft and to the compass in src.ino and has access to a few public functions:

This function sets up the imu by checking if the imu that is a field of our DestinationSelection class has imu.setupIMU(1) is true, otherwise it restarts the imu.

This sets our boolean state variable, selecting, to true meaning that the process of selecting a destination has started.

This sets our selecting variable to false, meaning the process of selecting a destination is over

This sets the parameter char* building to the current building number which is found by getting the letters at index destination_building_index of the BUILDINGS char array.

This sets the parameter char* floor to the current floor number which is found by getting the letters at index destination_floor_index of the FLOORS char array.

This is where the work of destination selection happens. It is called once per loop in the src.ino file if the current state is destination selection. Taking in a button flag, the function updates checks the imu readings that determine if the device is tilted or not and determines what state, value, and index various variables should be so that selecting an destination works properly.

const uint8_t MAX_BUILDING_NAME_LENGTH = 10;

const uint8_t MAX_NODE_ID_LENGTH = 10;

enum class NavigationState {IDLE, LOCATING, ROUTING, NAVIGATING};

struct Location {

double latitude;

double longitude;

};

struct NavigationInstructions {

char curr_building[MAX_BUILDING_NAME_LENGTH];

char next_building[MAX_BUILDING_NAME_LENGTH];

char curr_node[MAX_NODE_ID_LENGTH];

char next_node[MAX_NODE_ID_LENGTH];

double dist_next_node;

double dir_next_node;

bool has_arrived;

double eta;

char dest_node[MAX_NODE_ID_LENGTH];

char dest_building[MAX_NODE_ID_LENGTH];

};

class Navigation {

static const uint16_t NAVIGATION_UPDATE_LOOP_DURATION;

static char USER_ID[];

NavigationState state;

ApiClient* apiClient;

Compass* compass;

TFT_eSPI* tft;

uint32_t navigation_update_timer;

bool navigating;

struct Location location;

uint8_t current_floor;

char destination[MAX_BUILDING_NAME_LENGTH];

uint8_t destination_floor;

uint32_t compass_update_display_timer;

struct NavigationInstructions navigation_instructions;

void display_navigation_instructions();

void display_routing_message();

public:

Navigation(ApiClient* client, Compass* _compass, TFT_eSPI* _tft);

void fetch_current_location();

void fetch_navigation_instructions();

void begin_navigation(int _current_floor, char* _destination, int _destination_floor);

void end_navigation();

int navigate();

};const int BUTTON_PIN = 45;

Button button(BUTTON_PIN);

// Define global variables

TFT_eSPI tft = TFT_eSPI();

ApiClient apiClient;

Compass compass(&tft, 100);

Navigation navigator(&apiClient, &compass, &tft);

DestinationSelection destination_selection(&tft, &compass);

uint8_t current_floor = 1;

char destination_building[2];

char destination_floor[2];

enum global_state

{

START,

CALIBRATE,

DESTINATION_SELECTION,

NAVIGATING,

CONFIRM_CANCEL,

ARRIVED

};

global_state state = START;

int destination_selection_flag;

int navigation_flag;

void setup() {

Serial.begin(115200); // Set up serial

while(!Serial);

pinMode(BUTTON_PIN, INPUT_PULLUP);

tft.init(); // init screen

tft.setRotation(2); // adjust rotation

tft.setTextSize(1); // default font size, change if you want

tft.fillScreen(TFT_BLACK); // fill background

tft.setTextColor(TFT_GREEN, TFT_BLACK); // set color of font to hot pink foreground, black background

tft.println("Tiny Tim booting... \nplease wait\n\n");

tft.println("Initializing Wifi...");

apiClient.initialize_wifi_connection();

tft.println("Initializing Compass...");

compass.initialize();

display_start_message();

}

void loop(){

compass.refresh_data(); // This must be done each time through the loop

compass.calc_quaternion(); // This must be done each time through the loop

int button_flag = button.update();

global_update(button_flag);

}This is the main Arduino executable file. It is fairly straightforward in that it implements the main state machine defined in the system design and puts together every component. In other words, this is the file that is run our device and this is where every component truly comes together. This includes everything from button presses, to the api client, to the navigator, to destination selection, to the compass, and even the TFT. It is in this file that we initialize the different components and use the flags returned to transition into / out of different states.

The tests were meant to mimic external calls to each component as if they were being called from src.ino.

This folder held the manual tests for the compass. The goal here was to test all components of the compass as if they were being called externally. This essentially served as an integration test for the compass component. This culminated in a script (i.e. src.ino) file we could run that would allow us to verify that the compass was working as intended without all the additional components from the main file for our project (the one that contains every component).

This folder held the tests for the ApiClient. We tested basic functionality, i.e. connecting to WiFi, sending requests to Google’s Api and our server and receiving a response, and correctly parsing responses.

These tests were manual tests where we uploaded the code to the esp and made sure we could go through the destination selection and print the intended destination to the Serial Monitor. We tested whether it worked for different buildings and floor.

These tests were manual tests to make sure the Navigation component was interfacing properly with the ApiClient, TFT, and Compass. This tested the navigation state machine and public facing methods such ad navigate() as well.

This folder contains all the json and csv files that are used to create our graph representation and find the shortest path as requested by the user.

Stores the cached graph.

{

"1.1.1.b": {

"adj": {

"1.1.2.b": 50.07943898479174,

"3.1.1.b": 59.09590907598268,

"kc.1.1.b": 59.63313912406474,

"kc.1.2.b": 81.8064152694634

},

"node": {

"building": "1",

"floor": 1,

"id": "1.1.1.b",

"location": {

"lat": 42.3579921,

"lon": -71.0918238

},

"node_type": "b"

}

},

"1.1.2.b": {

"adj": {

"1.1.1.b": 50.07943898479174,

"1.1.3.b": 61.34118524172251

},

"node": {

"building": "1",

"floor": 1,

"id": "1.1.2.b",

"location": {

"lat": 42.3578077,

"lon": -71.0923785

},

"node_type": "b"

}

},

}Stores the cached all pairs shortest path.

{

"[\"1.1.1.b\", \"1\", 1]": {

"destination": "1.1.1.b",

"distance": 0,

"path": [

"1.1.1.b"

],

"source": "1.1.1.b"

},

"[\"1.1.1.b\", \"10\", 1]": {

"destination": "10.1.1.b",

"distance": 229.6896995033066,

"path": [

"1.1.1.b",

"3.1.1.b",

"3.1.2.b",

"3.1.3.b",

"3.1.4.b",

"10.1.1.b"

],

"source": "1.1.1.b"

},

"[\"1.1.1.b\", \"11\", 1]": {

"destination": "11.1.1.b",

"distance": 189.66206780700244,

"path": [

"1.1.1.b",

"3.1.1.b",

"3.1.2.b",

"3.1.3.b",

"11.1.1.b"

],

"source": "1.1.1.b"

},

}Stores all nodes with latitude and longitude coordinates and node name. Note that the lat, lon are switched (this was a challenge we ran into when our system wasn't working and we had to debug why)

| WKT | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| POINT (-71.0919165 42.3579359) | 1.1 | " " |

| POINT (-71.0923785 42.3578077) | 1.2 | " " |

| POINT (-71.0926422 42.3582736) | 1.3 | " " |

| [nodes.csv] |

Stores all edges.

| WKT | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LINESTRING (-71.0926422 42.3582736, -71.0923785 42.3578077, -71.0919165 42.3579359) | 1 | "" |

| LINESTRING (-71.0932001 42.359221, -71.0926583 42.3593478) | 3-7 | "" |

| LINESTRING (-71.0932001 42.359221, -71.0929104 42.358662) | 5-7 | "" |

| [edges.csv] |

Stores the coordinates of all polygons for each building along with the name of the building.

| WKT | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| POLYGON ((-71.0913105 42.3596288, -71.0924504 42.3592681, -71.0916377 42.3579699, -71.0905139 42.3583366, -71.0913105 42.3596288)) | kc | "" |

| POLYGON ((-71.0932422 42.3590174, -71.0928215 42.3583521, -71.0926172 42.3584189, -71.0930249 42.3590957, -71.0932422 42.3590174)) | 5 | "" |

| POLYGON ((-71.0935704 42.3595512, -71.0932422 42.3590174, -71.0929079 42.3591311, -71.0929347 42.3591766, -71.0927376 42.3592411, -71.0928342 42.3594016, -71.0930353 42.3593342, -71.0932378 42.3596682, -71.0935704 42.3595512)) | 7 | "" |

| [polygons.csv] |

This is the bulk of our server functionality. This class contains:

class Location:

pass

class Route:

pass

class Node:

pass

class Edge:

pass

class Graph:

pass

class Polygon:

pass

def parse_polygons(polygons_csv_file_path: str) -> Dict[str, Polygon]:

pass

def parse_nodes(nodes_csv_file_path: str, polygons: Dict[str, Polygon], floor: Optional[int], node_type: NodeType = NodeType.BUILDING) -> List[Node]:

pass

def parse_edges(edges_csv_file_path: str, nodes: List[Node]) -> List[Tuple[str, str]]:

pass

def create_graph(nodes: List[Node], edges: List[Tuple[str, str]], num_floors: int) -> Graph:

pass

def create_all_graph_components(num_floors: int = 2, use_cache: bool = True):

pass

def compare_cache_vs_no_cache():

pass

def get_current_building(polygons: Dict[str, Polygon], point: Location) -> str:

pass

def calculate_eta(distance: float, avg_velocity: float = 1.34112):

pass

def calculate_distance(point_1: Location, point_2: Location) -> distance.meters:

pass

def calculate_direction(first_point, second_point):

passThis file contains the logic for handling requests and returning appropriate responses. This implements the functionality defined in graph.py.

class RequestValues:

pass

class Response:

pass

def request_handler(request):

passIn this file we run a series of automated tests to check that our functions return the expected values. We check each of the following aspects of the functionality of our server, by partitioning the input space and completing tests:

- ClosestNodeTests

- CurrentBuildingTests

- DijkstraTests

- GraphTests

- EdgeTests

- NodeTests

- DirectionTests

- PolygonTests

The beginning of week 0 was focused on brainstorming ideas for our final project and deciding on something we thought was both feasible and creative. After lots of discussion, we decided to go with the TinyTim project because we believed we could do an effective job and it was a project we thought would be beneficial to students at MIT. The project proposal we wrote highlighted the goals of the project along with software design, hardware parts we would need, and potential setbacks we could face along the way.

This week we focused on representing a group of MIT's buildings as a weighted graph (from hard coded nodes and edge weights) which was done through google maps. We also implemented a single shortest path algorithm that had some unit tests to show it could work with the nodes on our hard coded graph. Along with the addition of this code to the server side, we also created some Arduino code which handled sending and receiving a GET request from our team's server and also parsed the response. Finally, we utilized functionality from the wiki word chooser project earlier in the semester to have a system to select buildings that our server could find a path to.

After implementing a graph of some MIT buildings and an algorithm to find a path between buildings (nodes), we now began to create a python query response which would send the ESP32 relevant information about a user's journey. On top of this, we also focused on updating the system for selecting a building by creating a hard-coded dictionary of all the buildings/nodes that we have available on our team's server. Finally, we separately integrated a compass to our ESP32 which required independent testing and calibrating of an IMU that had compass functionality. As a result, we were able to have an arrow on our LCD display which pointed consistently north. This functionality would come in handy later to have an arrow giving directions as to which way a user would need to walk on their path.

Now that we had a solid server side for our application, we turned our focus to optimizing server side performance and cleaning up the code that would run on the ESP32. To optimize the server side performance, the server team created a script which ran through the csv files we had created with all the nodes for the MIT buildings we had mapped and found the shortest paths between nodes to save to a separate file. Having a separate file with all the predetermined shortest paths between nodes meant we could send server responses much faster. On the ESP32 side of our codebase, we started to refactor our code to have classy versions of our compass, destination selection, and server querying. Our final goal for this week was to integrate all the classy versions of our code into one overarching state machine, but we had to push this goal back to the following week.

Our final week of the project was focused on creating unit tests for each independent class that would be running on the ESP32 (in the state machine). This strategy meant we could test all of the components of our final system independently to make sure they work functioning correctly. We also added an option in our state machine to transition to a calibration mode before moving to giving the user directions. Finally, we compiled all the code together to make a functioning project and recorded a working journey in the MIT buildings we had mapped. Unfortunately, we ran into a problem with losing connection to WiFi but managed to get the ESP32 connected to hotspot to offer a more reliable functionality.

- Represent group of MIT's building as weighted graph (from hard coded nodes and edge weights)

- Demonstrate path finding

- Have functioning server side which returns relative user journey information

- Add more detail to current graph representation of MIT buildings

- Edges can be added to our graph overlay, exported to an edges.csv file, and fed to our program. Our code will automatically parse the edges, weight them, and generate our graph.

- Multiple floors, elevators and stairs

- Optimize server side performance by precomputing shortest paths and indexing into this list upon a server request.

- Parse JSON object and display the current node, distance to next node, direction to next node, has arrived and eta on the arduino display (LCD) Parsing JSON Video

- We refactored the Navigation functions and state variables into a class that has a .h and a .cpp file so we can call the necessary functions on an instance of the Navigation class.

- Individual navigation tests

- Implement finite state machine for continually fetching current lat, lon and sending POST request to server ApiClient Video

- We refactored the API Client processes into a class that has a .h and a .cpp file so we can call the necessary functions on an instance of the ApiClient class.

- Individual ApiClient test cases ApiClient Test Video

- Deciding on an IMU: MPU9250 Initial IMU Demo Video

- Compass arrow pointing North Compass Pointing North Video

- Refactor compass code into "classy compass". We compiled all compass code into a class with a header and cpp. We isolated the portions of setup and the public functions needed in the main src script and navigation state machine and call those functions on an instance of the compass class.

- Isolate IMU calibration in its own function for quick and easy calibration of new IMUs IMU calibration video

- Individual compass tests Compass Test Video

- Consistently get building and room numbers and be able to print them to the lcd screen Consistent Building Selection Video

- Implement finite state machine for selecting destination

- Autocomplete for building / room input Autocomplete Video

- We refactored the destination selection process into a class that has a .h and a .cpp file so we can call the necessary functions on an instance of the destination_selection class.

- Individual destination selection tests Destination Test Video

- Successfully arriving at a nearby Destination (w/ msg): Arriving at Destination video

- Getting some smooth turns Turning Video

- WiFi failures! Wifi Fail Video

- See top of page for complete product video!

WiFi/Hotspot Functionality: We ran into some issues during our project with WiFi/hotspot connectivity so there is room for improvement in this category. We would have to edit our ApiClient/Navigation class to account for the fact that users could potentially lose connection at any given time. If this is the case, then they would not be able to send http requests, ultimately crashing TinyTim. There are a couple of workarounds:

- Before each query to our team’s server and google’s API, we would check if we are still connected to any WiFi. If we are, continue with the query as usual, but if not, then we will keep showing the previous directions while we try to reconnect to a new WiFi router.

- We can walk around MIT campus and check what the strongest MAC address connection is based on the region within MIT campus we are in. We can then automatically connect to a specific MAC address based on which building we are in when the WiFi has gone down.

Heuristics for Paths: Even though our server-side code is fully functioning to give users a shortest path between buildings, we could add some heuristics in the future. For instance, if a user wants to take the path with the most cover (if it is raining outside) then we could add a heuristic to account for this. Moreover, if a user wants to be given a path with the least amount of foot traffic, we could also account for this with a heuristic.

Joseph Gross

Kathleen Allden

Adam Snowdon

Billy Menken

Daniel Papacica