- Sub-Bit Packing

- How To Use

- Benchmark

This C++ library is designed to efficiently store state values, essentially unsigned integers with a limited value range, by using sub-bit packing. It offers random read/write access to all elements in constant time.

Storing states bitwise can result in significant memory wastage. This C++ library aims to conserve memory by employing arithmetic packing of values while maintaining constant-time read/write access for each element (see Benchmark). This table provides a comparison of the space saved when comparing arithmetically packed values to bit-packed values.

The trade-off is a runtime overhead for setting/retrieving values due to the necessary calculations instead of simple addressing. Therefore, if the number of states you intend to store doesn't provide a spatial benefit (e.g., powers of 2), it's advisable to stick with bitwise packing for faster runtime performance.

Conversely, this library becomes valuable when you need to pack more tightly on platforms where memory is the limiting factor, such as embedded systems.

It's important to note that this library does not employ compression algorithms or block encoding. It merely packs the uncompressed storage for the elements without relying on the actual values within the data block.

enum class MyState: uint8_t

{

First,

Second,

Third,

};

MyState a_lot_of_states[10000];sizeof(MyState) will give you 1 byte

sizeof(a_lot_of_states) will, therefore, give you 10000

In order to store 10000 values we are using 10000 bytes or 80000 bits which could store up to

This naive method to store states is a huge waste of memory.

The first step to mitigate wasting memory is to store the states in the least amount of bits necessary. To store three states, we need a maximum of 2 bits.

So to store 10000 states we would only need 20000 bits or 2500 bytes.

We can already save 75% of storage (10000 vs. 2500) with this method.

The above method works perfectly fine if the number of states a value can represent can make use of the bits it is stored in. But there is still wasted memory if that is not the case. As you may have already figured out, when using 2 bits to represent 3 states, there is one extra unused state:

00 First

01 Second

10 Third

11 unused

When storing many values, we can save 25% memory here by not storing the values bit-packed but arithmetically-packed instead. This way, even the unused state will be used to hold information.

Internally the values are held in an array of 32-bit data chunks. Instead of bitwise packing, however, a form of arithmetic coding is used to store the values. The advantage of this is that you can pack (the same or) more values in a given data buffer than with traditional bitwise packing. The number of values (

A 32-bit data block (

Retrieving a value works like this:

The overall space saved compared to simple bit-packing can be calculated with the following formula:

Lets say you want to store values with 3 different states:

This means an arithmetically packed buffer will be able to store 25% more values than with traditional packing. See this table for more values.

Here's a table for values with different number of states and how much space is saved compared to bitwise packing. Both done in 32-bit words:

| Number of states per value | Space advantage |

|---|---|

| 3 | 25% |

| 5 | 30% |

| 6 | 20% |

| 7 | 10% |

| 9 | 25% |

| 10,11 | 12.5% |

| 17-23 | 16.66% |

| 33-40 | 20% |

| 65-84 | 25% |

| 1025-1625 | 50% |

The space saved for all other values is 0%. That means it is not better nor worse than bitwise packing. However, the access times are slower. Therefore, sub-bit-packing is not optimal for such use cases.

Lets say you want to store

Filling in 5 we get something like 13,78.. meaning that every 32-bit word wastes around 0.78 state values. We can calculate the number of wasted (whole) bits per 32-bit word using this formula:

Again, filling in 5 gets us 1, meaning there is 1 bit in every 32-bit word that goes unused. (For a higher number of states, the number of unused bits per word can even go as high as 10)

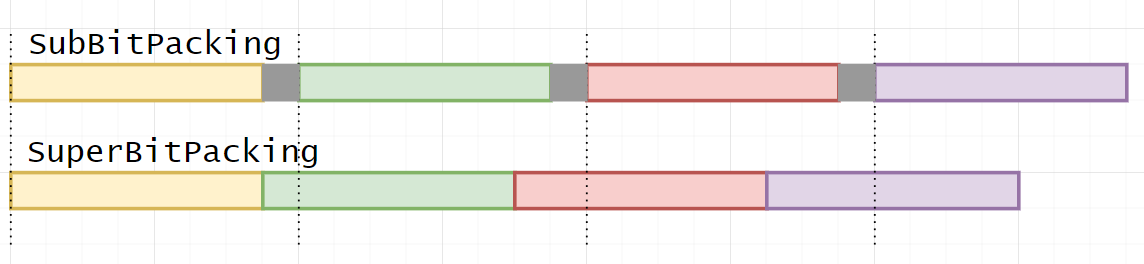

Saving memory in these cases is as easy as shifting the 32-bit sub-bit-packed words closer together for the amount of unused bits. This library refers to this technique as SuperBitPacking. Here is a visual comparison to SubBitPacking:

The drawback here is an additional access overhead because the values need to be shifted before they can be accessed to do the normal SubBitPacking calculation.

This library provides several types of arrays to store state values in. Internally, each array holds an array of uint32_t. They only differ in the level of compression. The following listings are in order of memory usage (high to low) and access time (fast to slow).

Stores values as described here. If the number of bits needed to store states does not evenly devide 32, some values are stored across two 32-bit words. When accessed, these words are shifted accordingly to get/set values. This is done to prevent wasting bits.

Stores values as described here. Slower than BitPackedArray but saves memory.

Stores values as described here. If the number of unused bits per 32-bit word is 0 then this array behaves exactly as SubBitPackedArray. If the number of unused bits is > 0, the access times are slower than SubBitPackedArray but the space saved is even greater.

The following results stem from running Code on an ESP32. The code was built with -Os optimization. Each array holds 100,000 values and was read from and written to 10,000,000 times. Here are a few different number of states and the correlating benchmark results:

3 States

| Array | Bytes used for 100,000 values | 10,000,000 write/read times (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| BitPackedArray | 25000 | 3485 |

| SubBitPackedArray | 20000 | 5789 |

| SuperBitPackedArray | 20000 | 5789 |

12 States

| Array | Bytes used for 100,000 values | 10,000,000 write/read times (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| BitPackedArray | 50000 | 3443 |

| SubBitPackedArray | 50000 | 5239 |

| SuperBitPackedArray | 45316 | 10174 |

17 States

| Array | Bytes used for 100,000 values | 10,000,000 write/read times (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| BitPackedArray | 62500 | 3967 |

| SubBitPackedArray | 57144 | 5955 |

| SuperBitPackedArray | 51788 | 10640 |

Additionally to the packing of homogeneous state values, this library provides a way to store multiple values with a different number of possible states each in a single struct. This is called a SubBitPackedStruct.

It is also possible to store multiple SubBitPackedStructs loosely in a SubBitPackedStructArray or tightly packed in a SuperBitPackedStructArray. See SubBitPackedStruct for how to do this.

The calculation for the underlying 32-bit value of SubBitPackedArray entries is explained in this section.

The underlying value of a SubBitPackedStruct is calculated in a similar way. It holds SubBitPackedArray is that instead of mutliplying a value

This means the underlying SubBitPackedStruct value

A state value can be retrieved with this formula:

Here is a code example and a few calculations to demonstrate what is going on behind the scenes:

// Create struct and set initial values to 2, 4 and 7

SubBitPackedStruct<3, 5, 9> myStruct{2, 4, 7};

myStruct.get(1); // Get the state of the 5-state value (4)Number of states:

State values:

Multiplicators:

Sum of values:

Retrieve state value 1:

As you have seen, this library relies heavily on mathematical calculations. This has the potential to greatly decrease run-time performance. To mitigate this, this library does most of the necessary calculations at compile-time. The only things not precalculated are related to getting/setting values.

To keep backwards compatibility with C++11 a few hurdles had to be jumped.

constexpr functions are very limited on what they were allowed to do back then. Therefore, most of the implementations in this library consist of only a return statement of concatenated ternary conditional operations.

Also, the default C++ math library only provides constexpr support from C++26 onwards. To avoid dependencies on third-party math libraries, the needed functionality was either self-implemented or bypassed altogether (no log(), for example). Check out compiletime.h to see all implementations.

Here are a few examples on what is going on when compiling Objects from this library:

When calculating the underlying values for a SubBitPackedArray a lot of exponential calculations need to be done. To avoid the run-time overhead, instead of doing the calculations over and over again, a lookup table is calculated once at compile-time. This is done in two parts: There is a generator, that creates an std::array (inspired by this blog post) and then there is this pow implementation that generates the actual values when fed into the generator:

template <uint16_t Base>

constexpr uint32_t Pow(uint8_t exponent)

{

return (exponent == 0) ? 1 : (Base * Pow<Base>(exponent - 1));

}The lookup table for a SubBitPackedStruct is similar, however, each table value needs to be the product of all the numbers before the current value. Feeding the following implementation into the generator does the trick:

template <uint16_t Base>

constexpr uint32_t VariadicStatePow(uint8_t)

{

return 1;

}

template <uint16_t Base, uint16_t... Extra>

constexpr auto VariadicStatePow(uint8_t exponent) ->

typename std::enable_if<sizeof...(Extra) != 0, uint32_t>::type

{

return (exponent == 0) ? 1 : Base * VariadicStatePow<Extra...>(exponent - 1);

}

For example, creating a lookup table this way:

GenerateLut<3>(VariadicStatePow<4, 8, 9>);will yield an array that contains the values [1, 4, 32].

All the necessary size calculations are done at compile-time as well. The numbers for how many state values a 32-bit SubBitPackedArray data chunk can hold, however, are precalculated for all possible values (2 - 65535). The constexpr function NumberOfStatesPer4ByteSubBitPackedWord merely returns these precalculated values. This is done in order to circumvent using the log() function, as this cannot be done at compile-time.

To calculate the number of 32-bit chunks a SuperBitPacked(Struct)Array needs to allocate, more information is needed, like the highest amount of bits a given array entry really needs.

This is done by actually counting bits instead of calculation, because, again, most mathematical functions are out of reach for this.

Basic usage examples for this library.

Let's say you have a 3-Color-Display with a resolution of 800x480 (== 384000 values). Depending on how much run-time you can spare to save memory, you can choose between these three arrays:

kt::BitPackedArray<3, 384000> displayBuffer{};

kt::SubBitPackedArray<3, 384000> displayBuffer{};

kt::SuperBitPackedArray<3, 384000> displayBuffer{};Or on the heap:

auto displayBuffer = new kt::BitPackedArray<3, 384000>{};

auto displayBuffer = new kt::SubBitPackedArray<3, 384000>{};

auto displayBuffer = new kt::SuperBitPackedArray<3, 384000>{}; enum class Color

{

WHITE = 0,

BLACK

RED

}

size_t pixel_index = ...

displayBuffer->set(pixel_index, static_cast<uint16_t>(Color::RED)); Color color = static_cast<Color>(displayBuffer->get(pixel)); displayBuffer->getByteSize();If you want to pack multiple values, that hold a different amount of states each, into a single struct you can achieve this as follows:

kt::SubBitPackedStruct<3,5,6> stateStruct{};This struct now holds 3 values, that can have 3, 5 and 6 different states, respectively.

Accessing values is done by specifying the corresponding index:

stateStruct.get(0); //Gets the state information from the 3-state value

stateStruct.set(1, SOME_STATE); //Sets the state for the 5-state valueWhen storing multiple (in this case 1000) SubBitPackedStructs you can choose between the following two arrays, depending on your need for access performance and memory efficiency:

auto stateStructArray = new kt::SubBitPackedStructArray<SubBitPackedStruct<3,5,6>, 1000>{};

auto stateStructArray = new kt::SuperBitPackedStructArray<SubBitPackedStruct<3,5,6>, 1000>{};Getting/Setting values can be done by stating the array index for the wanted struct and also the value index for the selected struct:

stateStructArray.get(187, 1); //Get the 5-state value of the struct with index 187

stateStructArray.set(313, 2, SOME_STATE); //Set the 6-state value of the struct with index 313By default this library uses no exceptions. However, you can enable exceptions by setting the compile flag KT_ENABLE_EXCEPTIONS. This activates array boundary checks but will also slow down array accesses.

Here are some benchmark numbers:

For an array with 50,000 elements, the memory usage for states between 1 and 100 is as shown in the following figure:

-

bitpacked: Natively packed states, like those used in bitfields. For example, 3 states can fit into 2 bits and do not occupy 1 byte. -

subbitpacked: The same states but packed with our sub-bit algorithm. -

superbitpacked: Subbitpacked values that are also bitpacked by shifting consecutive blocks into the leftover bits from the preceding blocks.

Time consumption for 10 million reads:

One notable thing is that the read iterator has quite good performance because it doesn't need to calculate the location where the bits are stored but can simply move within a stream of values.

Currently, there has been minimal manual code optimization, with the exception of the Compile Time Calculations for required power-lookup-tables and sizes.

Currently, there is only a read-iterator available for the subbitpackedarray. Our plan is to implement both read and write iterators for all array implementations.

To provide a more user-friendly way to access struct members, we are planning to introduce named field accessors in addition to indexed access.