Click

if you like the project. Your contributions are heartily ♡ welcome.

- 50+ React Coding Practice Questions

- React Quick Reference

- Redux Quick Reference

- Jest Quick Reference

- React Best Practices

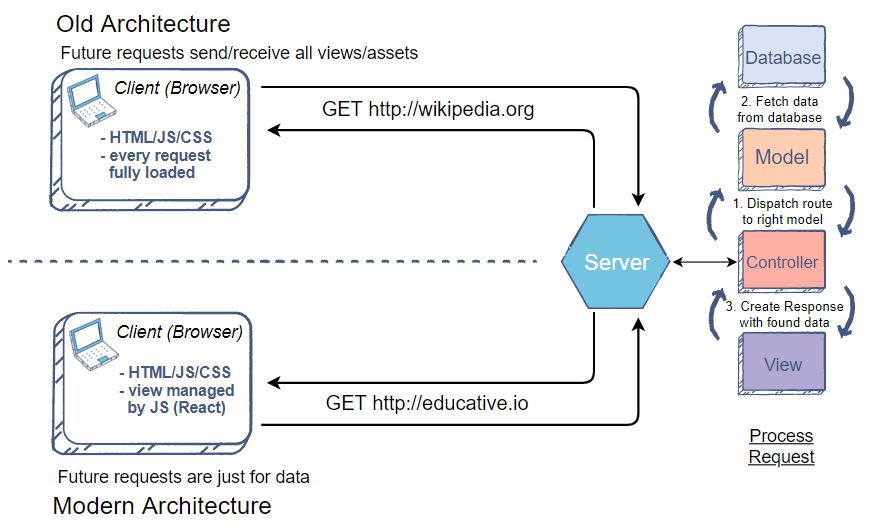

React is a JavaScript library created for building fast and interactive user interfaces for web and mobile applications. It is an open-source, component-based, front-end library responsible only for the application view layer.

The main objective of ReactJS is to develop User Interfaces (UI) that improves the speed of the apps. It uses virtual DOM (JavaScript object), which improves the performance of the app. The JavaScript virtual DOM is faster than the regular DOM. We can use ReactJS on the client and server-side as well as with other frameworks. It uses component and data patterns that improve readability and helps to maintain larger apps.

Read More:

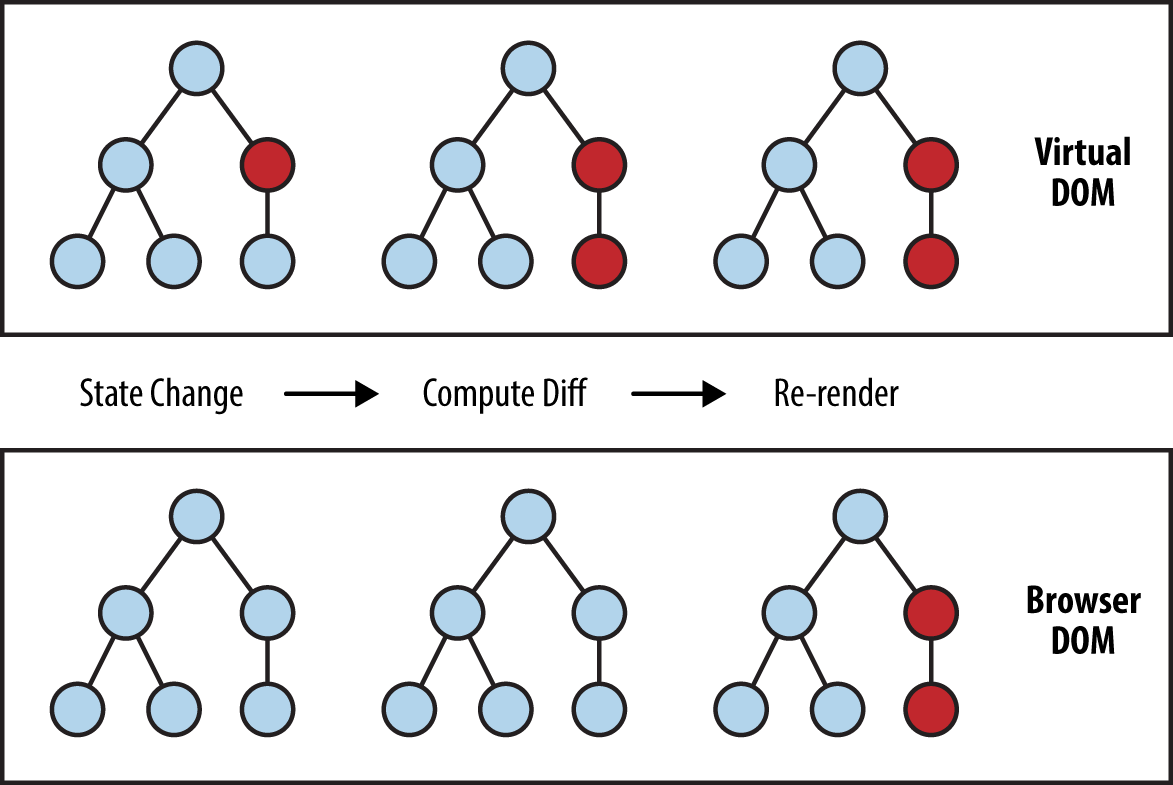

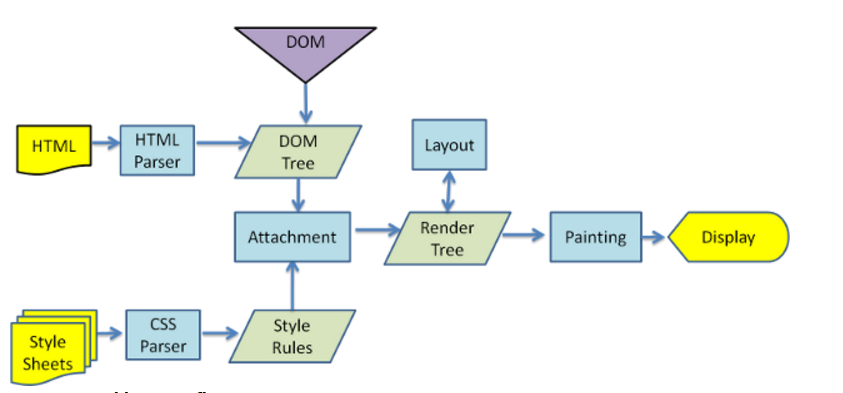

While building client-side apps, a team at Facebook developers realized that the DOM is slow (The Document Object Model (DOM) is an application programming interface (API) for HTML and XML documents. It defines the logical structure of documents and the way a document is accessed and manipulated). So, to make it faster, React implements a virtual DOM that is basically a DOM tree representation in Javascript. So when it needs to read or write to the DOM, it will use the virtual representation of it. Then the virtual DOM will try to find the most efficient way to update the browsers DOM.

Unlike browser DOM elements, React elements are plain objects and are cheap to create. React DOM takes care of updating the DOM to match the React elements. The reason for this is that JavaScript is very fast and it is worth keeping a DOM tree in it to speedup its manipulation.

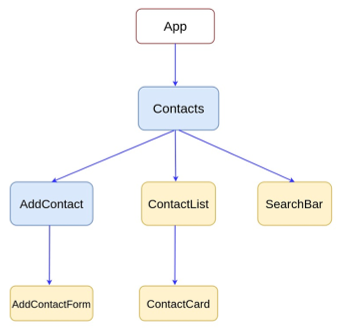

Components are the building blocks of any React app and a typical React app will have many of these. Simply put, a component is a JavaScript class or function that optionally accepts inputs i.e. properties(props) and returns a React element that describes how a section of the UI (User Interface) should appear.

A react application is made of multiple components, each responsible for rendering a small, reusable piece of HTML. Components can be nested within other components to allow complex applications to be built out of simple building blocks. A component may also maintain internal state – for example, a TabList component may store a variable corresponding to the currently open tab.

Example: Class Component

class Welcome extends React.Component {

render() {

return <h1>Hello, World!</h1>

}

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

The presentational components are concerned with the look, container components are concerned with making things work.

For example, this is a presentational component. It gets data from its props, and just focuses on showing an element

const Users = props => (

<ul>

{props.users.map(user => (

<li>{user}</li>

))}

</ul>

)On the other hand this is a container component. It manages and stores its own data, and uses the presentational component to display it.

class UsersContainer extends React.Component {

constructor() {

this.state = {

users: []

}

}

componentDidMount() {

axios.get('/users').then(users =>

this.setState({ users: users }))

)

}

render() {

return <Users users={this.state.users} />

}

}// Importing combination

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

// Wrapping components with braces if no default exports

import { Button } from './Button';

// Default exports ( recommended )

import Button from './Button';

class DangerButton extends Component {

render()

{

return <Button color="red" />;

}

}

export default DangerButton;

// or export DangerButton;By using default you express that's going to be member in that module which would be imported if no specific member name is provided. You could also express you want to import the specific member called DangerButton by doing so: import { DangerButton } from './comp/danger-button'; in this case, no default is needed

It is a programming paradigm that uses statements that change a program's state.

var string = "Hi there , I'm a web developer";

var removeSpace = "";

for (var i = 0; i < i.string.length; i++) {

if (string[i] === " ") removeSpace += "-";

else removeSpace += string[i];

}

console.log(removeSpace);In this example, we loop through every character in the string, replacing spaces as they occur. Just looking at the code, it doesn't say much. Imperative requires lots of comments in order to understand code. Whereas in the declarative program, the syntax itself describes what should happen and the details of how things happen are abstracted way.

It is a programming paradigm that expresses the logic of a computation without describing its control flow.

Example:

const { render } = ReactDOM

const Welcome = () => (

<div id="App">

//your HTML code

//your react components

</div>

)

render(

<App />,

document.getElementById('root')

)React is declarative. Here, the Welcome component describes the DOM that should be rendered. The render function uses the instructions declared in the component to build the DOM, abstracting away the details of how the DOM is to be rendered. We can clearly see that we want to render our Welcome component into the element with the ID of 'target'.

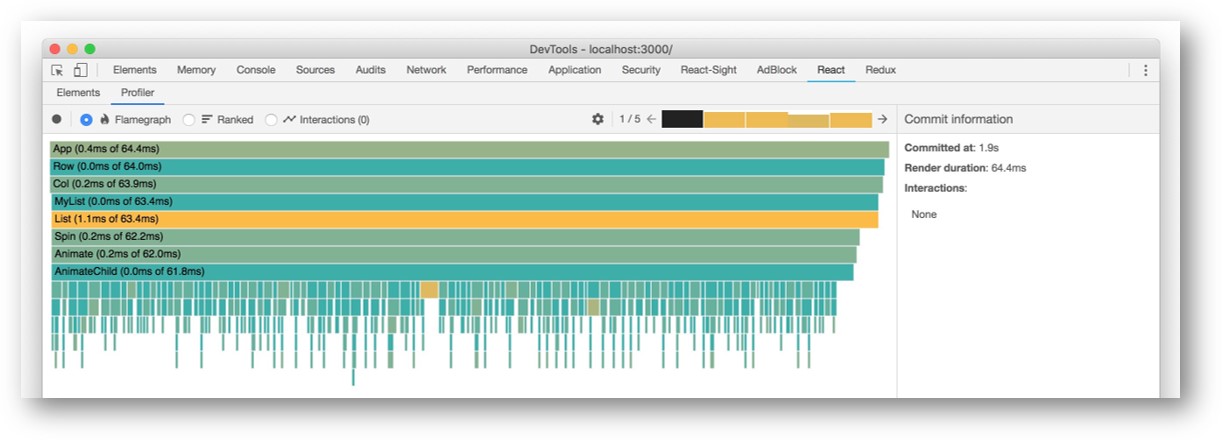

The usual pattern for rendering lists of components often ends with delegating all of the responsibilities of each child component to the entire list container component. But with a few optimizations, we can make a change in a child component not cause the parent component to re-render.

Example: using custom shouldComponentUpdate()

class AnimalTable extends React.Component<Props, never> {

shouldComponentUpdate(nextProps: Props) {

return !nextProps.animalIds.equals(this.props.animalIds);

}

...Here, shouldComponentUpdate() will return false if the props its receiving are equal to the props it already has. And because the AnimalTable is receiving just a List of string IDs, a change in the adoption status won't cause AnimalTable to receive a different set of IDs.

Example: Lets create a simple component and store the data in the state.

import React, { Component } from 'react'

class Table extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props) /** since we are extending class Table so we have to use super in order to override

Component class constructor **/

this.state = { // state is by default an object

employees: [

{ id: 1, name: 'Swarna Sachdeva', age: 28, email: 'swarna@email.com' },

{ id: 2, name: 'Sarvesh Date', age: 33, email: 'sarvesh@email.com' },

{ id: 3, name: 'Diksha Meka', age: 46, email: 'diksha@email.com' },

{ id: 4, name: 'Tanvi Deol', age: 45, email: 'tanvi@email.com' },

{ id: 4, name: 'Aapti Kara', age: 32, email: 'aapti@email.com' }

]

}

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>React Dynamic Table</h1>

</div>

)

}

}

export default Table; // Exporting a component make it reusableNow we want to print out employees data in the Dom. We often use map function in react to itearate over array.

Lets write a separate function for table data and calling it in our render method. This approach will make our code cleaner and easier to read.

renderTableData() {

return this.state.employees.map((employee, index) => {

const { id, name, age, email } = employee // Destructuring

return (

<tr key={id}>

<td>{id}</td>

<td>{name}</td>

<td>{age}</td>

<td>{email}</td>

</tr>

)

})

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1 id='title'>React Dynamic Table</h1>

<table id='employees'>

<tbody>

{this.renderTableData()}

</tbody>

</table>

</div>

)

}Now we will write another method for table header.

renderTableHeader() {

let header = Object.keys(this.state.employees[0])

return header.map((key, index) => {

return <th key={index}>{key.toUpperCase()}</th>

})

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1 id='title'>React Dynamic Table</h1>

<table id='employees'>

<tbody>

<tr>{this.renderTableHeader()}</tr>

{this.renderTableData()}

</tbody>

</table>

</div>

)

}Object.Keys() gives us all the keys of employees in the form of array and we stored it in a variable header. So we can iterate the header (array) using map method.

It is a simple object that describes a DOM node and its attributes or properties. It is an immutable description object and you can not apply any methods on it.

const element = <h1>React Element Example!</h1>;

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById('app'));It is a function or class that accepts an input and returns a React element. It has to keep references to its DOM nodes and to the instances of the child components.

function Message() {

return <h2>React Component Example!</h2>;

}

ReactDOM.render(<Message />, document.getElementById('app'));Advantages:

- It relies on a virtual-dom to know what is really changing in UI and will re-render only what has really changed, hence better performance wise

- JSX makes components/blocks code readable. It displays how components are plugged or combined with.

- React data binding establishes conditions for creation dynamic applications.

- Prompt rendering. Using comprises methods to minimise number of DOM operations helps to optimise updating process and accelerate it. Testable. React native tools are offered for testing, debugging code.

- SEO-friendly. React presents the first-load experience by server side rendering and connecting event-handlers on the side of the user:

- React.renderComponentToString is called on the server.

- React.renderComponent() is called on the client side.

- React preserves markup rendered on the server side, attaches event handlers.

Limitations:

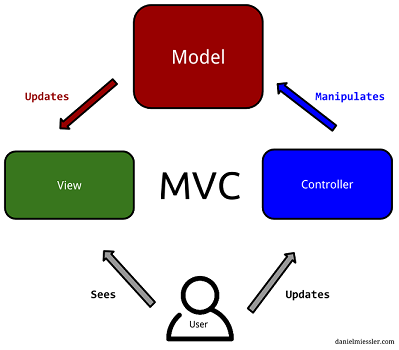

- Learning curve. Being not full-featured framework it is requered in-depth knowledge for integration user interface free library into MVC framework.

- View-orientedness is one of the cons of ReactJS. It should be found 'Model' and 'Controller' to resolve 'View' problem.

- Not using isomorphic approach to exploit application leads to search engines indexing problems.

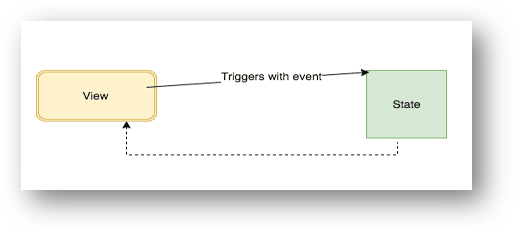

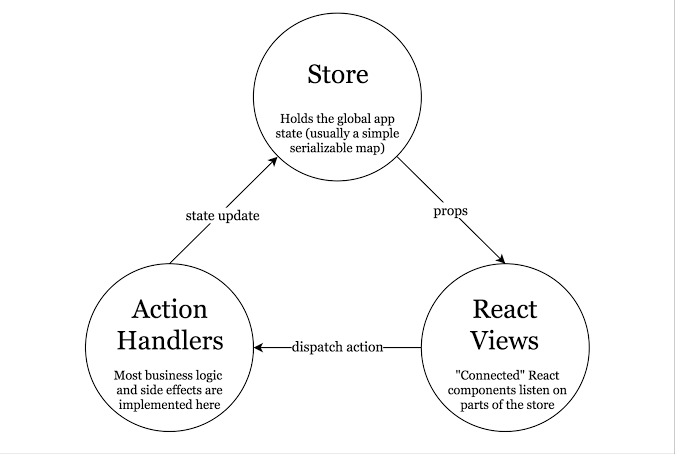

It is also known as one-way data flow, which means the data has one, and only one way to be transferred to other parts of the application. In essence, this means child components are not able to update the data that is coming from the parent component. In React, data coming from a parent is called props.

In React this means that:

- state is passed to the view and to child components

- actions are triggered by the view

- actions can update the state

- the state change is passed to the view and to child components

The view is a result of the application state. State can only change when actions happen. When actions happen, the state is updated. One-way data binding provides us with some key advantages

- Easier to debug, as we know what data is coming from where.

- Less prone to errors, as we have more control over our data.

- More efficient, as the library knows what the boundaries are of each part of the system.

In React, a state is always owned by one component. Any changes made by this state can only affect the components below it, i.e its children. Changing state on a component will never affect its parent or its siblings, only the children will be affected. This is the main reason that the state is often moved up in the component tree so that it can be shared between the components that need to access it.

JSX allows us to write HTML elements in JavaScript and place them in the DOM without any createElement() or appendChild() methods. JSX converts HTML tags into react elements. React uses JSX for templating instead of regular JavaScript. It is not necessary to use it, however, following are some pros that come with it.

- It is faster because it performs optimization while compiling code to JavaScript.

- It is also type-safe and most of the errors can be caught during compilation.

- It makes it easier and faster to write templates.

Example:

import React from 'react'

class App extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

Hello World!

</div>

)

}

}

export default App⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

JSX is a JavaScript Expression:

JSX expressions are JavaScript expressions too. When compiled, they actually become regular JavaScript objects. For instance, the code below:

const hello = <h1 className = "greet"> Hello World </h1>will be compiled to

const hello = React.createElement {

type: "h1",

props: {

className: "greet",

children: "Hello World"

}

}Since they are compiled to objects, JSX can be used wherever a regular JavaScript expression can be used.

React DOM escapes any values embedded in JSX before rendering them. Thus it ensures that you can never inject anything that's not explicitly written in your application. Everything is converted to a string before being rendered.

For example, you can embed user input as below,

class JSXInjectionExample extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

userContent: `JSX prevents Injection Attacks Example

<script src="http://example.com/malicious-script.js><\/script>`

};

}

render() {

return <div>User content: {this.state.userContent}</div>;

}

}

ReactDOM.render(<JSXInjectionExample/>, document.getElementById("root"));The React 17 release provides support for a new version of the JSX transform. There are three major benefits of new JSX transform,

- It enables you to use JSX without having to import React.

- The compiled output relatively improves the bundle size.

- The future improvements provides the flexibility to reduce the number of concepts to learn React.

Browsers don't understand JSX, so most React users rely on a compiler like Babel or TypeScript to transform JSX code into regular JavaScript. Normally when we us JSX, the compiler transforms it into React function calls that the browser can understand.

Let's take an example to look at the main differences between the old and the new transform,

import React from 'react';

function App() {

return <h1>Hello World</h1>;

}Under the hood, the old JSX transform would turn the JSX into regular JavaScript:

import React from 'react';

function App() {

return React.createElement('h1', null, 'Hello world');

}Because JSX was compiled into React.createElement(), React needed to be in scope if you used JSX. Hence, the reason react is being imported everywhere you use JSX. Also, there are some performance improvements and simplifications that that are not allowed by React.createElement().

The new JSX transform doesn't require any React imports

import React from 'react';

function App() {

return <h1>Hello World</h1>;

}The new Jsx transform would compile it to:

// The import would be Inserted by the compiler (don't import it yourself)

import {jsx as _jsx} from 'react/jsx-runtime';

function App() {

return _jsx('h1', { children: 'Hello world' });

}It is possible with latest version (>=16.2). Below are the possible options:

render() {

return false

}render() {

return null

}render() {

return []

}render() {

return <React.Fragment></React.Fragment>

}render() {

return <></>

}Note that React can also run on the server side so, it will be possible to use it in such a way that it doesn't involve any DOM modifications (but maybe only the virtual DOM computation).

Note: Returning undefined does not work.

Often we need to store information associated with a DOM element. This data might not be useful for displaying data to the DOM, but it is helpful for developers to access additional data. Custom attributes allow you to attach other values onto an HTML element.

Custom attributes are supported natively in React 16. This means that adding a custom attribute to an element is now as simple as adding it to a render function, like so:

Example:

// Custom DOM Attribute

render() {

return (

<div custom-attribute="some-value" />

);

}

// Data Attribute ( starts with "data-" )

render() {

return (

<div data-id="10" />

);

}

// ARIA Attribute ( starts with "aria-" )

render() {

return (

<button aria-label="Close" onClick={onClose} />

);

}Writing comments in React components can be done just like comment in regular JavaScript classes and functions.

React comments:

function App() {

// Single line Comment

/*

* multi

* line

* comment

**/

return (

<h1>My Application</h1>

);

}JSX comments:

export default function App() {

return (

<div>

{/* A JSX comment */}

<h1>My Application</h1>

</div>

);

}- Functional components are basic JavaScript functions. These are typically arrow functions but can also be created with the regular function keyword.

- Sometimes referred to as

statelesscomponents as they simply accept data and display them in some form; that is they are mainly responsible for rendering UI. - React lifecycle methods (for example,

componentDidMount()) cannot be used in functional components. - There is no render method used in functional components.

- These are mainly responsible for UI and are typically presentational only (For example, a Button component).

- Functional components can accept and use props.

- Functional components should be favored if you do not need to make use of React state.

Example:

function Welcome(props) {

return <h1>Hello, {props.name}</h1>;

}

const element = <Welcome name="World!" />;

ReactDOM.render(

element,

document.getElementById('root')

);- Class components make use of ES6 class and extend the Component class in React.

- Sometimes called

statefulcomponents as they tend to implement logic and state. - React lifecycle methods can be used inside class components (for example,

componentDidMount()). - We pass

propsdown to class components and access them withthis.props. - Class-based components can have

refsto underlying DOM nodes. - Class-based components can use

shouldComponentUpdate()andPureComponent()performance optimisation techniques.

Example:

class Welcome extends React.Component {

render() {

return <h1>Hello, {this.props.name}</h1>;

}

}

const element = <Welcome name="World!" />;

ReactDOM.render(

element,

document.getElementById('root')

);staticmethodsconstructor()getChildContext()componentWillMount()componentDidMount()componentWillReceiveProps()shouldComponentUpdate()componentWillUpdate()componentDidUpdate()componentWillUnmount()- click handlers or event handlers like

onClickSubmit()oronChangeDescription() - getter methods for render like

getSelectReason()orgetFooterContent() - optional render methods like

renderNavigation()orrenderProfilePicture() render()

Conditional rendering is a term to describe the ability to render different user interface (UI) markup if a condition is true or false. In React, it allows us to render different elements or components based on a condition.

Element Variables:

You can use variables to store elements. This can help you conditionally render a part of the component while the rest of the output doesn't change.

function LogInComponent(props) {

const isLoggedIn = props.isLoggedIn;

if (isLoggedIn) {

return <UserComponent />;

}

return <GuestComponent />;

}

ReactDOM.render(

// Try changing to isLoggedIn={true}:

<LogInComponent isLoggedIn={false} />,

document.getElementById('root')

);Inline If-Else with Conditional Operator:

render() {

const isLoggedIn = this.state.isLoggedIn;

return (

<div>

{isLoggedIn

? <LogoutButton onClick={this.handleLogoutClick} />

: <LoginButton onClick={this.handleLoginClick} />

}

</div>

);

}You can prevent component from rendering by returning null based on specific condition. This way it can conditionally render component.

In the example below, the <WarningBanner /> is rendered depending on the value of the prop called warn. If the value of the prop is false, then the component does not render:

function WarningBanner(props) {

if (!props.warn) {

return null;

}

return (

<div className="warning">

Warning!

</div>

);

}class Page extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {showWarning: true};

this.handleToggleClick = this.handleToggleClick.bind(this);

}

handleToggleClick() {

this.setState(state => ({

showWarning: !state.showWarning

}));

}

render() {

return (

<div>

{ /* Prevent component render if value of the prop is false */}

<WarningBanner warn={this.state.showWarning} />

<button onClick={this.handleToggleClick}>

{this.state.showWarning ? 'Hide' : 'Show'}

</button>

</div>

);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(

<Page />,

document.getElementById('root')

);⚝ prevent component from rendering

Data passed in from a parent component. props are read-only in the child component that receives them. However, callback functions can also be passed, which can be executed inside the child to initiate an update.

Example:

function Welcome(props) {

return <h1>Hello, {props.name}</h1>;

}

const element = <Welcome name="World!" />;When you declare a component as a function or a class, it must never modify its own props.

Consider this sum function:

function sum(a, b) {

return a + b;

}Such functions are called pure because they do not attempt to change their inputs, and always return the same result for the same inputs. All React components must act like pure functions with respect to their props. A component should only manage its own state, but it should not manage its own props.

In fact, props of a component is concretely "the state of the another component (parent component)". So props must be managed by their component owner. That's why all React components must act like pure functions with respect to their props (not to mutate directly their props).

The defaultProps is a React component property that allows you to set default values for the props argument. If the prop property is passed, it will be changed. The defaultProps can be defined as a property on the component class itself to set the default props for the class. defaultProps is used for undefined props, not for null props.

class MessageComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>Hello, {this.props.value}.</div>

)

}

}

// Default Props

MessageComponent.defaultProps = {

value: 'World'

}

ReactDOM.render(

<MessageComponent />,

document.getElementById('default')

)

ReactDOM.render(

<MessageComponent value='Folks'/>,

document.getElementById('custom')

)React JSX doesn't support variable interpolation inside an attribute value, but we can put any JS expression inside curly braces as the entire attribute value.

Approach 1: Putting js expression inside curly braces

<img className="image" src={"images/" + this.props.image} />Approach 2: Using ES6 template literals.

<img className="image" src={`images/${this.props.image}`} />Example:

class App extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<img

alt="React Logo"

// Using ES6 template literals

src={`${this.props.image}`}

/>

</div>

);

}

}

export default App;React JSX has exactly two ways of passing true, <MyComponent prop /> and <MyComponent prop={true} /> and exactly one way of passing false <MyComponent prop={false} />.

Example:

const MyComponent = ({ prop1, prop2 }) => (

<div>

<div>Prop1: {String(prop1)}</div>

<div>Prop2: {String(prop2)}</div>

</div>

)

function App() {

return (

<div>

<MyComponent prop1={true} prop2={false} />

<MyComponent prop1 prop2 />

<MyComponent prop1={false} prop2 />

</div>

);

}The PropTypes.shape() validator can be used when describing an object whose keys are known ahead of time, and may represent different types.

Example:

import PropTypes from 'prop-types';

const Component = (props) => <div>Component badge: {props.badge ? JSON.stringify(props.badge) : 'none'}</div>

// PropTypes validation for the prop object

Component.propTypes = {

badge: PropTypes.shape({

src: PropTypes.string.isRequired,

alt: PropTypes.string.isRequired,

}),

}

const App = () => (

<div>

<Component badge={{ src: 'horse.png', alt: 'Running Horse' }}/>

{/*<Component badge={{src:null, alt: 'this one gives an error'}}/>*/}

<Component/>

</div>

);The PropTypes.objectOf() validator is used when describing an object whose keys might not be known ahead of time, and often represent the same type.

Example:

import PropTypes from 'prop-types';

// Expected prop object - dynamic keys (i.e. user ids)

const myProp = {

25891102: 'Shila Jayashri',

34712915: 'Employee',

76912999: 'shila.jayashri@email.com'

};

// PropTypes validation for the prop object

MyComponent.propTypes = {

myProp: PropTypes.objectOf(PropTypes.number)

};Using PropTypes.oneOfType() says that a prop can be one of any number of types. For instance, a phone number may either be passed to a component as a string or an integer:

const Component = (props) => <div>Phone Number: {props.phoneNumber}</div>

Component.propTypes = {

phoneNumber: PropTypes.oneOfType([

PropTypes.number,

PropTypes.string

]),

}

const App = () => (

<div>

<Component phoneNumber={04403472916}/>

{/*<Component phoneNumber={"2823788557"}/>*/}

</div>

);This is data maintained inside a component. It is local or owned by that specific component. The component itself will update the state using the setState() function.

Example:

class Employee extends React.Component {

constructor() {

super()

this.state = {

id: 100,

name: "Alex K"

}

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<p>{this.state.id}</p>

<p>{this.state.name}</p>

</div>

)

}

}

export default EmployeeEven if state is updated synchronously, props are not, it means we do not know props until it re-renders the parent component. The objects provided by React (state, props, refs) are consistent with each other and if you introduce a synchronous setState you could introduce some bugs.

setState() does not immediately mutate this.state() but creates a pending state transition. Accessing this.state() after calling this method can potentially return the existing value. There is no guarantee of synchronous operation of calls to setState() and calls may be batched for performance gains.

This is because setState() alters the state and causes rerendering. This can be an expensive operation and making it synchronous might leave the browser unresponsive. Thus the setState() calls are asynchronous as well as batched for better UI experience and performance.

A callback function which will be invoked when setState() has finished and the component is re-rendered.

The setState() is asynchronous, which is why it takes in a second callback function. Typically it's best to use another lifecycle method rather than relying on this callback function, but it is good to know it exists.

this.setState(

{ username: 'Alex' },

() => console.log('setState has finished and the component has re-rendered.')

)The setState() will always lead to a re-render unless shouldComponentUpdate() returns false. To avoid unnecessary renders, calling setState() only when the new state differs from the previous state makes sense and can avoid calling setState() in an infinite loop within certain lifecycle methods like componentDidUpdate().

Instead of directly modifying the state using this.state(), we use this.setState(). This is a function available to all React components that use state, and allows us to let React know that the component state has changed. This way the component knows it should re-render, because its state has changed and its UI will most likely also change.

Example:

this.state = {

user: { name: 'Alex K', age: 28 }

}- Using Object.assign()

this.setState(prevState => {

let user = Object.assign({}, prevState.user); // creating copy of state variable user

user.name = 'New-Name'; // update the name property, assign a new value

return { user }; // return new object user object

})- Using spread syntax

this.setState(prevState => ({

user: { // object that we want to update

...prevState.user, // keep all other key-value pairs

name: 'New-Name' // update the value of specific key

}

}))When we use setState(), then apart from assigning to the object state react also rerenders the component and all it's children. Which we don't need in the constructor, since the component hasn't been rendered anyway.

Inside constructor uses this.state = {} directly, other places use this.setState({ })

Example:

import React, { Component } from 'react'

class Food extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = {

fruits: ['apple', 'orange'],

count: 0

}

}

render() {

return (

<div className = "container">

<h2> Hello!!!</h2>

<p> I have {this.state.count} fruit(s)</p>

</div>

)

}

}The setState() does not immediately mutate this.state() but creates a pending state transition. Accessing this.state after calling this method can potentially return the existing value.

There is no guarantee of synchronous operation of calls to setState() and calls may be batched for performance gains.

The setState() will always trigger a re-render unless conditional rendering logic is implemented in shouldComponentUpdate(). If mutable objects are being used and the logic cannot be implemented in shouldComponentUpdate(), calling setState() only when the new state differs from the previous state will avoid unnecessary re-renders.

Basically, if we modify this.state() directly, we create a situation where those modifications might get overwritten.

Example:

import React, { Component } from 'react'

class App extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = {

list: [

{ id: '1', age: 42 },

{ id: '2', age: 33 },

{ id: '3', age: 68 },

],

}

}

onRemoveItem = id => {

this.setState(state => {

const list = state.list.filter(item => item.id !== id)

return {

list,

}

})

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<ul>

{this.state.list.map(item => (

<li key={item.id}>

The person is {item.age} years old.

<button

type="button"

onClick={() => this.onRemoveItem(item.id)}

>

Remove

</button>

</li>

))}

</ul>

</div>

)

}

}

export default App⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

When using React, we should never mutate the state directly. If an object is changed, we should create a new copy. The better approach is to use Array.prototype.filter() method which creates a new array.

Example:

onDeleteByIndex(index) {

this.setState({

users: this.state.users.filter((item, i) => i !== index)

});

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

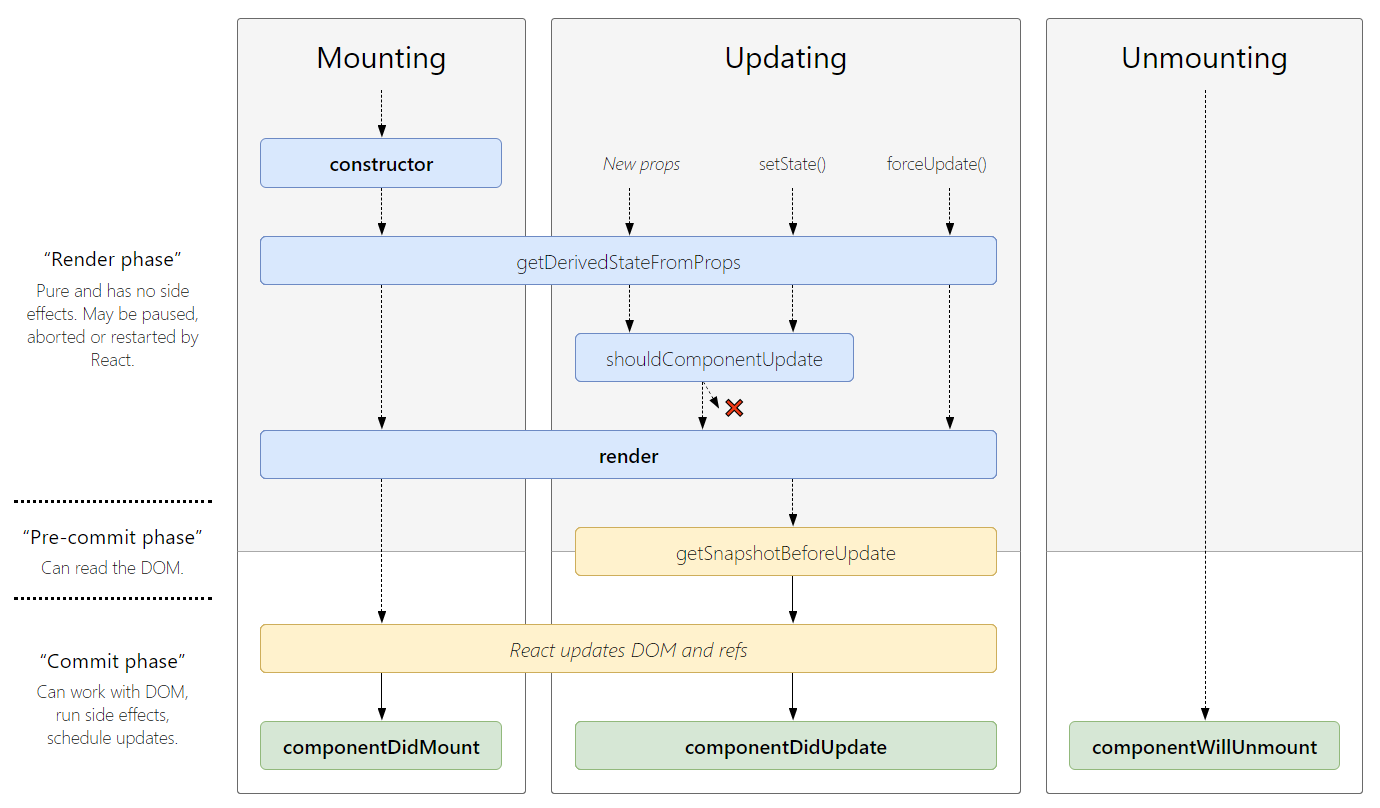

We should not call setState() in componentWillUnmount() because the component will never be re-rendered. Once a component instance is unmounted, it will never be mounted again.

The componentWillUnmount() is invoked immediately before a component is unmounted and destroyed. This method can be used to perform any necessary cleanup method, such as invalidating timers, canceling network requests, or cleaning up any subscriptions that were created in componentDidMount().

React components automatically re-render whenever there is a change in their state or props. A simple update of the state, from anywhere in the code, causes all the User Interface (UI) elements to be re-rendered automatically.

However, there may be cases where the render() method depends on some other data. After the initial mounting of components, a re-render will occur.

In the following example, the setState() method is called each time a character is entered into the text box. This causes re-rendering, which updates the text on the screen.

import React, { Component } from 'react'

import 'bootstrap/dist/css/bootstrap.css'

class Greeting extends Component {

state = {

fullname: '',

}

stateChange = (f) => {

const {name, value} = f.target

this.setState({

[name]: value,

})

}

render() {

return (

<div className="text-center">

<label htmlFor="fullname"> Full Name: </label>

<input type="text" name="fullname" onChange={this.stateChange} />

<div className="border border-primary py-3">

<h4> Greetings, {this.state.fullname}!</h4>

</div>

</div>

)

}

}

export default Greeting⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

The following example generates a random number whenever it loads. Upon clicking the button, the forceUpdate() function is called which causes a new, random number to be rendered:

class App extends React.Component {

constructor(){

super();

this.forceUpdateHandler = this.forceUpdateHandler.bind(this);

};

forceUpdateHandler(){

this.forceUpdate();

};

render(){

return(

<div>

<button onClick= {this.forceUpdateHandler} >FORCE UPDATE</button>

<h4>Random Number : { Math.random() }</h4>

</div>

);

}

}

export default App;Note: We should try to avoid all uses of forceUpdate() and only read from this.props and this.state in render().

The reason behind for this is that setState() is an asynchronous operation. React batches state changes for performance reasons, so the state may not change immediately after setState() is called. That means we should not rely on the current state when calling setState().

The solution is to pass a function to setState(), with the previous state as an argument. By doing this we can avoid issues with the user getting the old state value on access due to the asynchronous nature of setState().

Problem:

// assuming this.state.count === 0

this.setState({count: this.state.count + 1});

this.setState({count: this.state.count + 1});

this.setState({count: this.state.count + 1});

// this.state.count === 1, not 3⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

Solution:

this.setState((prevState) => ({

count: prevState.count + 1

}));

this.setState((prevState) => ({

count: prevState.count + 1

}));

this.setState((prevState) => ({

count: prevState.count + 1

}));

// this.state.count === 3 as expected⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

We can pass the old nested object using the spread operator and then override the particular properties of the nested object.

Example:

// Nested object

state = {

name: 'Vyasa Agarwal',

address: {

colony: 'Old Cross Rds, Mehdipatnam',

city: 'Patna',

state: 'Jharkhand'

}

};

handleUpdate = () => {

// Overriding the city property of address object

this.setState({ address: { ...this.state.address, city: "Ranchi" } })

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

| Props | State |

|---|---|

| Props are read-only. | State changes can be asynchronous. |

| Props are immutable. | State is mutable. |

| Props allow you to pass data from one component to other components as an argument. | State holds information about the components. |

| Props can be accessed by the child component. | State cannot be accessed by child components. |

| Props are used to communicate between components. | States can be used for rendering dynamic changes with the component. |

| Stateless component can have Props. | Stateless components cannot have State. |

| Props make components reusable. | State cannot make components reusable. |

| Props are external and controlled by whatever renders the component. | The State is internal and controlled by the React Component itself. |

If you are using ES6 or the Babel transpiler to transform your JSX code then you can accomplish this with computed property names.

inputChangeHandler : function (event) {

this.setState({ [event.target.id]: event.target.value });

// alternatively using template strings for strings

// this.setState({ [`key${event.target.id}`]: event.target.value });

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

The following lifecycle methods will be called when state changes. You can use the provided arguments and the current state to determine if something meaningful changed.

componentWillUpdate(object nextProps, object nextState)

componentDidUpdate(object prevProps, object prevState)In functional component, listen state changes with useEffect hook like this

export function MyComponent(props) {

const [myState, setMystate] = useState('initialState')

useEffect(() => {

console.log(myState, '- Has changed')

},[myState]) // <-- here put the parameter to listen

}There are 3 possible ways to achieve this

We can bind the handler when it is called in the render method using bind() method.

handleClick() {

// ...

}

<button onClick={this.handleClick.bind(this)}>Click</button> ⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

In this approach we are binding the event handler implicitly. This approach is the best if you want to pass parameters to your event.

handleClick() {

// ...

}

<button onClick={() => this.handleClick()}>Click</button> ⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

This has performance benefits as the events aren't binding every time the method is called, as opposed to the previous two approaches.

constructor(props) {

// This binding is necessary to make `this` work in the callback

this.handleClick = this.handleClick.bind(this);

}

handleClick() {

// ...

}

<button onClick={this.handleClick}>Click</button>⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

If you try to render a <label> element bound to a text input using the standard for attribute, then it produces HTML missing that attribute and prints a warning to the console.

<label for={'user'}>{'User'}</label>

<input type={'text'} id={'user'} />Since for is a reserved keyword in JavaScript, use htmlFor instead.

<label htmlFor={'user'}>{'User'}</label>

<input type={'text'} id={'user'} />React Components can add styling in the following ways:

In JSX, JavaScript expressions are written inside curly braces, and since JavaScript objects also use curly braces, the styling in the example above is written inside two sets of curly braces {{}}. Since the inline CSS is written in a JavaScript object, properties with two names, like background-color, must be written with camel case syntax:

class HeaderComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1 style={{backgroundColor: "lightblue"}}>Header Component Style!</h1>

<p>Add a little style!</p>

</div>

);

}

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

We can also create an object with styling information, and refer to it in the style attribute:

class HeaderComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

const mystyle = {

color: "white",

backgroundColor: "DodgerBlue",

padding: "10px",

fontFamily: "Arial"

};

return (

<div>

<h1 style={mystyle}>Header Component Style!</h1>

<p>Add a little style!</p>

</div>

);

}

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

You can write your CSS styling in a separate file, just save the file with the .css file extension, and import it in your application.

/** App.css **/

body {

background-color: #282c34;

color: white;

padding: 40px;

font-family: Arial;

text-align: center;

}import './App.css';

class HeaderComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Header Component Style!</h1>

<p>Add a little style!.</p>

</div>

);

}

}CSS Modules are convenient for components that are placed in separate files

/** mystyle.module.css **/

.bigblue {

color: DodgerBlue;

padding: 40px;

font-family: Arial;

text-align: center;

}import styles from './mystyle.module.css';

class HeaderComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1 className={styles.bigblue}>Header Component Style!</h1>

<p>Add a little style!.</p>

</div>

);

}

}Example: Using the ternary operator

class App extends Component {

constructor() {

super()

this.state = { isRed: true }

}

render() {

const isRed = this.state.isRed

return <p style={{ color: isRed ? 'red' : 'blue' }}>Example Text</p>

}

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

Using Spread operator:

const box = {

color: "green",

fontSize: '23px'

}

const shadow = {

background: "orange",

boxShadow: "1px 1px 1px 1px #cccd"

}

export default function App(){

return (

<div style={{...box, ...shadow}}>

<h1>Hello React</h1>

</div>

)

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

- React Transition Group

- React Spring

- Framer Motion

- React Motion

- React Move

- React Animations

- React Reveal

CSS module is a CSS file in which all class names and animation names are scoped locally by default. In the React application, we usually create a single .css file and import it to the main file so the CSS will be applied to all the components.

But using CSS modules helps to create separate CSS files for each component and is local to that particular file and avoids class name collision.

Benefits of CSS modules:

- Using CSS modules avoid namespace collision for CSS classes

- You can use the same CSS class in multiple CSS files

- You can confidently update any CSS file without worrying about affecting other pages

- Using CSS Modules generates random CSS classes when displayed in the browser

The Styled-components is a CSS-in-JS styling framework that uses tagged template literals in JavaScript and the power of CSS to provide a platform that allows you to write actual CSS to style React components.

The styled-components comes with a collection of helper methods, each corresponding to a DOM node for example <h1>, <header>, <button>, and SVG elements like line and path. The helper methods are called with a chunk of CSS, using an obscure JavaScript feature known as “tagged template literals”.

Example:

import styled from 'styled-components'

const Button = styled.button`

color: black;

//...

`

const WhiteButton = Button.extend`

color: white;

//...

`

render(

<div>

<Button>A black button, like all buttons</Button>

<WhiteButton>A white button</WhiteButton>

</div>

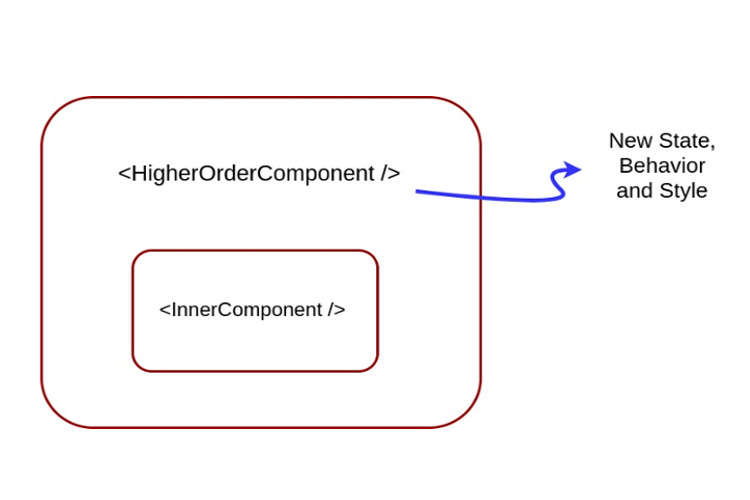

)A Higher-Order Component(HOC) is a function that takes a component and returns a new component. It is the advanced technique in React.js for reusing a component logic.

Higher-Order Components are not part of the React API. They are the pattern that emerges from React's compositional nature. The component transforms props into UI, and a higher-order component converts a component into another component. The examples of HOCs are Redux's connect and Relay's createContainer.

// HOC.js

import React, {Component} from 'react'

export default function Hoc(HocComponent){

return class extends Component{

render(){

return (

<div>

<HocComponent></HocComponent>

</div>

)

}

}

}// App.js

import React, { Component } from 'react'

import Hoc from './HOC'

class App extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

Higher-Order Component Example!

</div>

)

}

}

App = Hoc(App)

export default AppNotes

- We do not modify or mutate components. We create new ones.

- A HOC is used to compose components for code reuse.

- A HOC is a pure function. It has no side effects, returning only a new component.

Benefits:

- Importantly they provided a way to reuse code when using ES6 classes.

- No longer have method name clashing if two HOC implement the same one.

- It is easy to make small reusable units of code, thereby supporting the single responsibility principle.

- Apply multiple HOCs to one component by composing them. The readability can be improve using a compose function like in Recompose.

Problems:

- Boilerplate code like setting the displayName with the HOC function name e.g. (

withHOC(Component)) to help with debugging. - Ensure all relevant props are passed through to the component.

- Hoist static methods from the wrapped component.

- It is easy to compose several HOCs together and then this creates a deeply nested tree making it difficult to debug.

The term render prop refers to a technique for sharing code between React components using a prop whose value is a function.

In simple words, render props are simply props of a component where you can pass functions. These functions need to return elements, which will be used in rendering the components.

Example:

// Wrapper.js

class Wrapper extends React.Component {

state = {

count: 0

};

// Increase count

increment = () => {

const { count } = this.state;

return this.setState({ count: count + 1 });

};

render() {

const { count } = this.state;

return (

<div>

{this.props.render({ increment: this.increment, count: count })}

</div>

);

}

}// App.js

class App extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<Wrapper

render={({ increment, count }) => (

<div>

<h3>Render Props Counter</h3>

<p>{count}</p>

<button onClick={() => increment()}>Increment</button>

</div>

)}

/>

);

}

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

Benefits:

- Reuse code across components when using ES6 classes.

- The lowest level of indirection - it’s clear which component is called and the state is isolated.

- No naming collision issues for props, state and class methods.

- No need to deal with boiler code and hoisting static methods.

Problems:

- Caution using

shouldComponentUpdate()as the render prop might close over data it is unaware of. - There could also be minor memory issues when defining a closure for every render. But be sure to measure first before making performance changes as it might not be an issue for your app.

- Another small annoyance is the render props callback is not so neat in JSX as it needs to be wrapped in an expression. Rendering the result of an HOC does look cleaner.

It is possible to implement most higher-order components (HOC) using a regular component with a render prop. This way render props gives the flexibility of using either pattern.

Example:

function withMouse(Component) {

return class extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<Mouse render={mouse => (

<Component {...this.props} mouse={mouse} />

)}/>

);

}

}

}The Higher-Order Components, Render Props and Hooks are three patterns to implement state- or behaviour-* sharing between components. All three have their own use cases and none of them is a full replacement of the others.

Essentially HOC are similar to the decorator pattern, a function that takes a component as the first parameter and returns a new component. This is where you apply your crosscutting functionality.

Example:

function withExample(Component) {

return function(props) {

// cross cutting logic added here

return <Component {...props} />;

};

}A render prop is where a component’s prop is assigned a function and this is called in the render method of the component. Calling the function can return a React element or component to render.

Example:

render(){

<FetchData render={(data) => {

return <p>{data}</p>

}} />

}The React community is moving away from HOC (higher order components) in favor of render prop components (RPC). For the most part, HOC and render prop components solve the same problem. However, render prop components provide are gaining popularity because they are more declarative and flexible than an HOC.

Creating a higher order component basically involves manipulating WrappedComponent which can be done in two ways:

- Props Proxy

- Inheritance Inversion

Both enable different ways of manipulating the WrappedComponent.

In this approach, the render method of the HOC returns a React Element of the type of the WrappedComponent. We also pass through the props that the HOC receives, hence the name Props Proxy.

Example:

function ppHOC(WrappedComponent) {

return class PP extends React.Component {

render() {

return <WrappedComponent {...this.props}/>

}

}

}Props Proxy can be implemented via a number of ways

- Manipulating props

- Accessing the instance via Refs

- Abstracting State

- Wrapping the WrappedComponent with other elements

Inheritance Inversion allows the HOC to have access to the WrappedComponent instance via this keyword, which means it has access to the state, props, component lifecycle hooks and the render method.

Example:

function iiHOC(WrappedComponent) {

return class Enhancer extends WrappedComponent {

render() {

return super.render()

}

}

}Inheritance Inversion can be used in:

- Conditional Rendering (Render Highjacking)

- State Manipulation

Decorators provide a way of calling Higher-Order functions. It simply take a function, modify it and return a new function with added functionality. The key here is that they don't modify the original function, they simply add some extra functionality which means they can be reused at multiple places.

Example:

export const withUniqueId = (Target) => {

return class WithUniqueId extends React.Component {

uid = uuid();

render() {

return <Target {...this.props} uuid={this.uid} />;

}

};

}@withUniqueId

class UniqueIdComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return <div>Generated Unique ID is: {this.props.uuid}</div>;

}

}

const App = () => (

<div>

<h2>Decorators in React!</h2>

<UniqueIdComponent />

</div>

);Note: Decorators are an experimental feature in React that may change in future releases.

⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

Pure Components in React are the components which do not re-renders when the value of state and props has been updated with the same values. If the value of the previous state or props and the new state or props is the same, the component is not re-rendered. Pure Components restricts the re-rendering ensuring the higher performance of the Component

Features of React Pure Components

- Prevents re-rendering of Component if props or state is the same

- Takes care of

shouldComponentUpdate()implicitly State()andPropsare Shallow Compared- Pure Components are more performant in certain cases

Similar to Pure Functions in JavaScript, a React component is considered a Pure Component if it renders the same output for the same state and props value. React provides the PureComponent base class for these class components. Class components that extend the React.PureComponent class are treated as pure components.

It is the same as Component except that Pure Components take care of shouldComponentUpdate() by itself, it does the shallow comparison on the state and props data. If the previous state and props data is the same as the next props or state, the component is not Re-rendered.

React Components re-renders in the following scenarios:

setState()is called in Componentpropsvalues are updatedthis.forceUpdate()is called

In the case of Pure Components, the React components do not re-render blindly without considering the updated values of React props and state. If updated values are the same as previous values, render is not triggered.

Stateless Component

import { pure } from 'recompose'

export default pure ( (props) => {

return 'Stateless Component Example'

})Stateful Component

import React, { PureComponent } from 'react'

export default class Test extends PureComponent{

render() {

return 'Stateful Component Example'

}

}Example:

class Test extends React.PureComponent {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = {

taskList: [

{ title: 'Excercise'},

{ title: 'Cooking'},

{ title: 'Reacting'},

]

}

}

componentDidMount() {

setInterval(() => {

this.setState((oldState) => {

return { taskList: [...oldState.taskList] }

})

}, 1000)

}

render() {

console.log("TaskList render() called")

return (<div>

{this.state.taskList.map((task, i) => {

return (<Task

key={i}

title={task.title}

/>)

})}

</div>)

}

}

class Task extends React.Component {

render() {

console.log("task added")

return (<div>

{this.props.title}

</div>)

}

}

ReactDOM.render(<Test />, document.getElementById('app'))If you create a function inside a render method, it negates the purpose of pure component. Because the shallow prop comparison will always return false for new props, and each render in this case will generate a new value for the render prop. You can solve this issue by defining the render function as instance method.

Example:

class MouseTracker extends React.Component {

// Defined as an instance method, `this.renderTheCat` always

// refers to *same* function when we use it in render

renderTheCat(mouse) {

return <Cat mouse={mouse} />;

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Move the mouse around!</h1>

<Mouse render={this.renderTheCat} />

</div>

);

}

}Both functional-based and class-based components have the same downside: they always re-render when their parent component re-renders even if the props do not change.

Also, class-based components always re-render when its state is updated (this.setState() is called) even if the new state is equal to the old state. Moreover, when a parent component re-renders, all of its children are also re-rendered, and their children too, and so on.

That behaviour may mean a lot of wasted re-renderings. Indeed, if our component only depends on its props and state, then it shouldn't re-render if neither of them changed, no matter what happened to its parent component.

That is precisely what PureComponent does - it stops the vicious re-rendering cycle. PureComponent does not re-render unless its props and state change.

- We want to avoid re-rendering cycles of component when its props and state are not changed, and

- The state and props of component are immutable, and

- We do not plan to implement own

shouldComponentUpdate()lifecycle method.

On the other hand, we should not use PureComponent() as a base component if:

- props or state are not immutable, or

- Plan to implement own

shouldComponentUpdate()lifecycle method.

You can force re-renders of your components in React with a custom hook that uses the built-in useState() hook:

// Create a custom useForceUpdate hook with useState

const useForceUpdate = () => useState()[1];

// Call it inside your component

const Hooks = () => {

const forceUpdate = useForceUpdate();

return (

<button onClick={forceUpdate}>

Update me

</button>

);

};⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

The example above is equivalent to the functionality of the forceUpdate() method in class-based components. This hook works in the following way:

- The

useState()hook — and any other hook for that matter — returns an array with two elements, a value (with the initial value being the one you pass to the hook function) and an updater function. - In the above example, we are instantly calling the updater function, which in this case is called with

undefined, so it is the same as callingupdater(undefined).

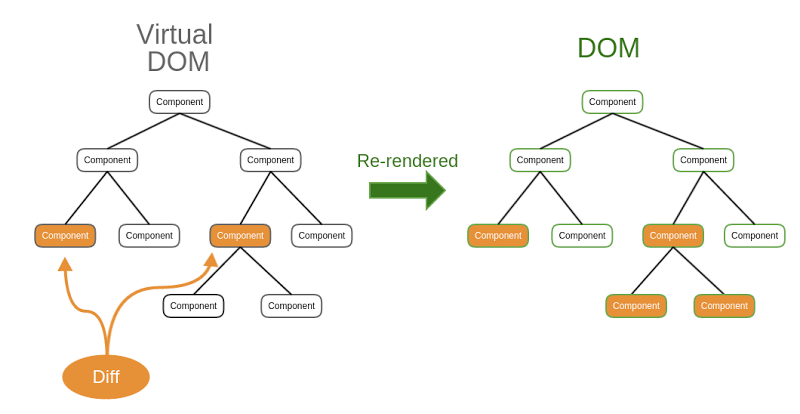

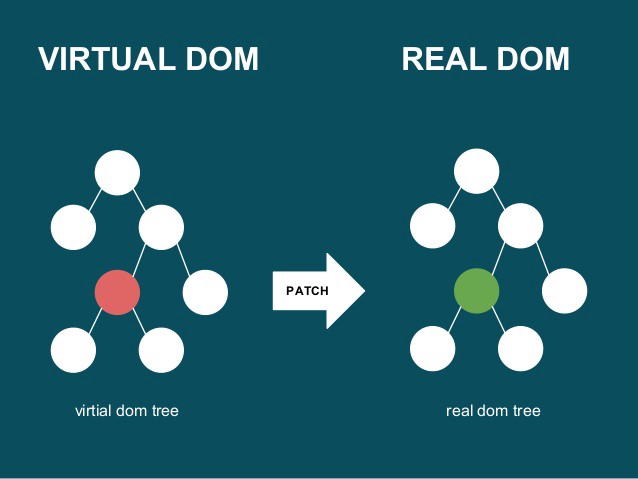

React Virtual DOM

In React, Each time the DOM updates or data of page changes, a new Virtual DOM representation of the user interface is made. It is just a lightweight copy or DOM.

Virtual DOM in React has almost same properties like a real DOM, but it can not directly change the content on the page. Working with Virtual DOM is faster as it does not update anything on the screen at the same time. In a simple way, Working with Virtual DOM is like working with a copy of real DOM nothing more than that.

Updating virtual DOM in ReactJS is faster because ReactJS uses

- It is efficient diff algorithm.

- It batched update operations

- It efficient update of sub tree only

- It uses observable instead of dirty checking to detect change

How Virtual DOM works in React

When we render a JSX element, each virtual DOM updates. This approach updates everything very quickly. Once the Virtual DOM updates, React matches the virtual DOM with a virtual DOM copy that was taken just before the update. By Matching the new virtual DOM with pre-updated version, React calculates exactly which virtual DOM has changed. This entire process is called diffing.

When React knows which virtual DOM has changed, then React updated those objects. and only those object, in the real DOM. React only updates the necessary parts of the DOM. React's reputation for performance comes largely from this innovation.

In brief, here is what happens when we update the DOM in React:

- The entire virtual DOM gets updated.

- The virtual DOM gets compared to what it looked like before you updated it. React matches out which objects have changed.

- The changed objects and the changed objects only get updated on the real DOM.

- Changes on the real DOM cause the screen to change finally.

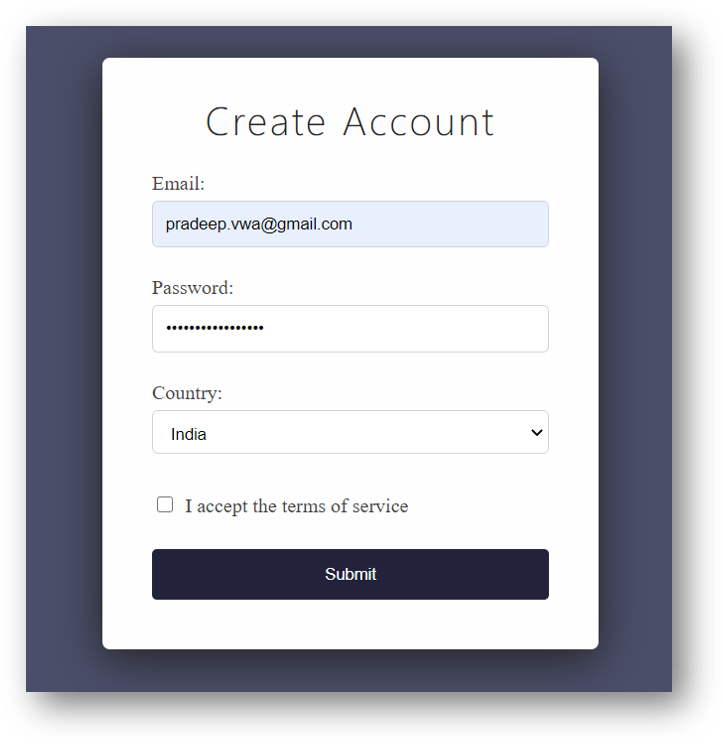

In a controlled component, form data is handled by a React component. The alternative is uncontrolled components, where form data is handled by the DOM itself.

Controlled Components

In a controlled component, the form data is handled by the state within the component. The state within the component serves as “the single source of truth” for the input elements that are rendered by the component.

Example:

import React, { Component } from 'react'

class App extends Component {

state = {

message: ''

}

updateMessage = (newText) => {

console.log(newText)

this.setState(() => ({

message: newText

}))

}

render() {

return (

<div className="App">

<div className="container">

<input type="text"

placeholder="Your message here.."

value={this.state.message}

onChange={(event) => this.updateMessage(event.target.value)}

/>

<p>the message is: {this.state.message}</p>

</div>

</div>

)

}

}

export default AppUncontrolled Components

Uncontrolled components act more like traditional HTML form elements. The data for each input element is stored in the DOM, not in the component. Instead of writing an event handler for all of your state updates, It uses ref to retrieve values from the DOM. Refs provide a way to access DOM nodes or React elements created in the render method.

import React, { Component } from 'react'

class App extends Component {

constructor(props){

super(props)

this.handleChange = this.handleChange.bind(this)

this.input = React.createRef()

}

handleChange = (newText) => {

console.log(newText)

}

render() {

return (

<div className="App">

<div className="container">

<input type="text"

placeholder="Your message here.."

ref={this.input}

onChange={(event) => this.handleChange(event.target.value)}

/>

</div>

</div>

)

}

}

export default AppIn React, the value (<input type="text" value="{value here}" />) attribute inside the input element will override any values that are typed in so in order to work around that, React provides another attribute called defaultValue (<input type="text" defaultValue="{value here}" />) that will pre-populate the input field with the defaultValue without overriding any value input by the user.

Example:

render() {

return (

<form onSubmit={this.handleSubmit}>

<label>

Name:

<input

defaultValue="Samir Chahal"

type="text"

ref={this.input} />

</label>

<input type="submit" value="Submit" />

</form>

);

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

In Class Components, when we pass the event handler function reference as a callback like this

<button type="button" onClick={this.handleClick}>Click Me</button>Example:

class App extends React.Component {

constructor( props ){

super( props );

this.handleClick = this.handleClick.bind(this);

}

handleClick(event){

// event handling logic

}

render() {

return (

<button type="button" onClick={this.handleClick}>Click Me</button>

);

}

}the event handler method loses its implicitly bound context. When the event occurs and the handler is invoked, the this value falls back to default binding and is set to undefined, as class declarations and prototype methods run in strict mode.

When we bind the this of the event handler to the component instance in the constructor, we can pass it as a callback without worrying about it losing its context.

Arrow functions are exempt from this behavior because they use lexical this binding which automatically binds them to the scope they are defined in.

The React.cloneElement() function returns a copy of a specified element. Additional props and children can be passed on in the function. This function is used when a parent component wants to add or modify the prop(s) of its children.

React.cloneElement(element, [props], [...children])The react.cloneElement() method accepts three arguments.

- element: Element we want to clone.

- props: props we need to pass to the cloned element.

- children: we can also pass children to the cloned element (passing new children replaces the old children).

Example:

import React from 'react'

export default class App extends React.Component {

// rendering the parent and child component

render() {

return (

<ParentComp>

<MyButton/>

<br></br>

<MyButton/>

</ParentComp>

)

}

}

// The parent component

class ParentComp extends React.Component {

render() {

// The new prop to the added.

let newProp = 'red'

// Looping over the parent's entire children,

// cloning each child, adding a new prop.

return (

<div>

{React.Children.map(this.props.children,

child => {

return React.cloneElement(child,

{newProp}, null)

})}

</div>

)

}

}

// The child component

class MyButton extends React.Component {

render() {

return <button style =

{{ color: this.props.newProp }}>

Hello World!</button>

}

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

The {this.props.children} is a special prop, automatically passed to every component, that can be used to render the content included between the opening and closing tags when invoking a component.

Example:

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>React Children Props Example</h1>

{this.props.children}

</div>

);

}

}

class OtherComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return <div>Other Component Props</div>;

}

}

ReactDOM.render(

<MyComponent>

<OtherComponent />

</MyComponent>,

document.getElementById("root")

);⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

The React.cloneElement() works if child is a single React element.

For almost everything {this.props.children} is used. Cloning is useful in some more advanced scenarios, where a parent sends in an element and the child component needs to change some props on that element or add things like ref for accessing the actual DOM element.

React.Children:

Since {this.props.children} can have one element, multiple elements, or none at all, its value is respectively a single child node, an array of child nodes or undefined. Sometimes, we want to transform our children before rendering them — for example, to add additional props to every child. If we wanted to do that, we'd have to take the possible types of this.props.children into account. For example, if there is only one child, we can not map it.

Example:

class Example extends React.Component {

render() {

return <div>

<div>Children ({this.props.children.length}):</div>

{this.props.children}

</div>

}

}

class Widget extends React.Component {

render() {

return <div>

<div>First <code>Example</code>:</div>

<Example>

<div>1</div>

<div>2</div>

<div>3</div>

</Example>

<div>Second <code>Example</code> with different children:</div>

<Example>

<div>A</div>

<div>B</div>

</Example>

</div>

}

}Output

First Example:

Children (3):

1

2

3

Second Example with different children:

Children (2):

A

Bchildren is a special property of React components which contains any child elements defined within the component, e.g. the <div> inside Example above. {this.props.children} includes those children in the rendered result.

The useState() is a Hook that allows to have state variables in functional components.

import React, { useState } from 'react'

const App = () => {

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0)

const handleIncrease = () => {

setCount(count + 1)

}

const handleDecrease = () => {

setCount(count - 1)

}

return (

<div>

Count: {count}

<hr />

<div>

<button type="button" onClick={handleIncrease}>

Increase

</button>

<button type="button" onClick={handleDecrease}>

Decrease

</button>

</div>

</div>

)

}The useState() function takes as argument a value for the initial state. In this case, the count starts out with 0. In addition, the hook returns an array of two values: count and setCount. It's up to you to name the two values, because they are destructured from the returned array where renaming is allowed.

Using Refs:

In React we can access the child's state using React.createRef(). We will assign a Refs for the child component in the parent component, then using Refs we can access the child's state.

// App.js

class App extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.ChildElement = React.createRef();

}

handleClick = () => {

const childelement = this.ChildElement.current;

childelement.getMsg("Message from Parent Component!");

};

render() {

return (

<div>

<Child ref={this.ChildElement} />

<button onClick={this.handleClick}>CLICK ME</button>

</div>

);

}

}// Child.js

class Child extends React.Component {

state = {

name: "Message from Child Component!"

};

getMsg = (msg) => {

this.setState({

name: msg

});

};

render() {

return <h2>{this.state.name}</h2>;

}

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

The React.memo() is a higher-order component that will memoize your component, very similar to PureComponent. It will shallowly compare current and new props of the component, and if nothing changes, React will skip the rendering of that component.

// Memo.js

const Text = (props) => {

console.log(`Text Component`);

return <div>Text Component re-render: {props.count} times </div>;

};

const MemoText = React.memo(

(props) => {

console.log(`MemoText Component`);

return <div>MemoText Component re-render: {props.count} times </div>;

},

(preprops, nextprops) => true

);// App.js

const App = () => {

console.log(`App Component`);

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<>

<h2>This is function component re-render: {count} times </h2>

<Text count={count} />

<MemoText count={count} />

<br />

<button

onClick={() => {

setCount(count + 1);

}}

>

CLICK ME

</button>

</>

);

};⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

The useState hook allows us to make our function components stateful. When called, useState() returns an array of two items. The first being our state value and the second being a function for setting or updating that value. The useState hook takes a single argument, the initial value for the associated piece of state, which can be of any Javascript data type.

import React, { useState } from 'react';

const Component = () => {

const [value, setValue] = useState(initial value)

...Example: State with Various Data Types

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const [color, setColor] = useState('#526b2d')

const [isHidden, setIsHidden] = useState(true)

const [products, setProducts] = useState([])

const [user, setUser] = useState({

username: '',

avatar: '',

email: '',

})It accepts a reducer function with the application initial state, returns the current application state, then dispatches a function.

Although useState() is a Basic Hook and useReducer() is an Additional Hook, useState() is actually implemented with useReducer(). This means useReducer() is primitive and we can use useReducer() for everything can do with useState(). Reducer is so powerful that it can apply for various use cases.

Example:

import React, { useReducer } from 'react'

const initialState = 0

const reducer = (state, action) => {

switch (action) {

case 'increment': return state + 1

case 'decrement': return state - 1

case 'reset': return 0

default: throw new Error('Unexpected action')

}

}

const ReducerExample = () => {

const [count, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, initialState)

return (

<div>

{count}

<button onClick={() => dispatch('increment')}>+1</button>

<button onClick={() => dispatch('decrement')}>-1</button>

<button onClick={() => dispatch('reset')}>reset</button>

</div>

)

}

export default ReducerExampleHere, we first define an initialState and a reducer. When a user clicks a button, it will dispatch an action which updates the count and the updated count will be displayed. We could define as many actions as possible in the reducer, but the limitation of this pattern is that actions are finite.

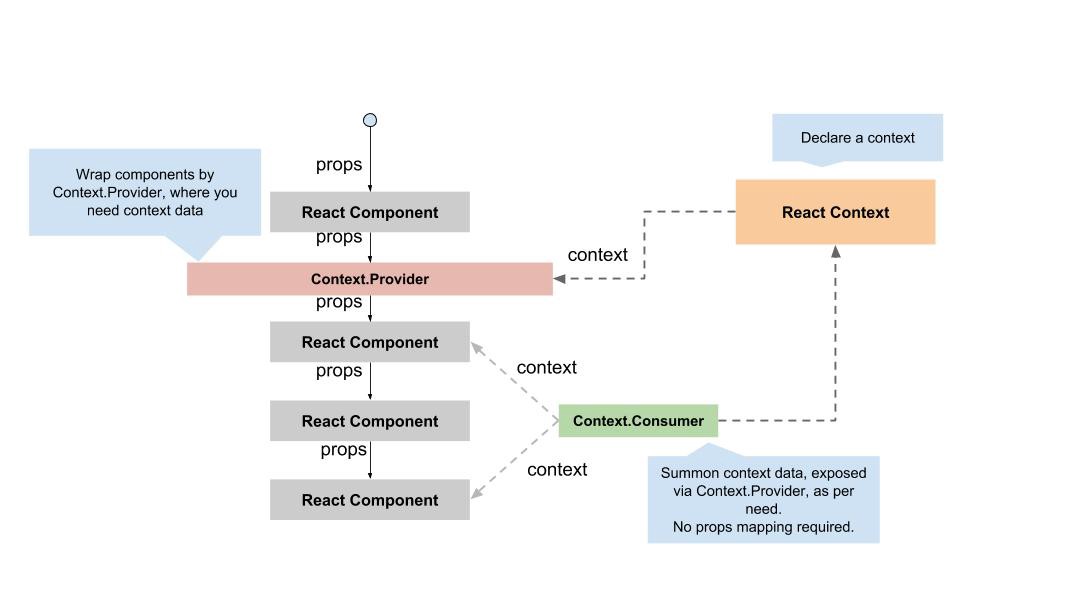

The React Context API allows to easily access data at different levels of the component tree, without having to pass data down through props.

Example:

// Counter.js

const { useState, useContext } = React;

const CountContext = React.createContext();

const Counter = () => {

const { count, increase, decrease } = useContext(CountContext);

return (

<h2>

<button onClick={decrease}>Decrement</button>

<span className="count">{count}</span>

<button onClick={increase}>Increment</button>

</h2>

);

};// App.js

const App = () => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const increase = () => {

setCount(count + 1);

};

const decrease = () => {

setCount(count - 1);

};

return (

<div>

<CountContext.Provider value={{ count, increase, decrease }}>

<Counter />

</CountContext.Provider>

</div>

);

};⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

Context provides a way to pass data or state through the component tree without having to pass props down manually through each nested component. It is designed to share data that can be considered as global data for a tree of React components, such as the current authenticated user or theme (e.g. color, paddings, margins, font-sizes).

Context API uses Context. Provider and Context. Consumer Components pass down the data but it is very cumbersome to write the long functional code to use this Context API. So useContext hook helps to make the code more readable, less verbose and removes the need to introduce Consumer Component. The useContext hook is the new addition in React 16.8.

Syntax:

const authContext = useContext(initialValue);The useContext accepts the value provided by React.createContext and then re-render the component whenever its value changes but you can still optimize its performance by using memorization.

The defaultValue argument is only used when a component does not have a matching Provider above it in the tree. This can be helpful for testing components in isolation without wrapping them. Passing undefined as a Provider value does not cause consuming components to use defaultValue.

const Context = createContext( "Default Value" );

function Child() {

const context = useContext(Context);

return <h2>Child1: {context}</h2>;

}

function Child2() {

const context = useContext(Context);

return <h2>Child2: {context}</h2>;

}

function App() {

return (

<>

<Context.Provider value={ "Initial Value" }>

<Child /> {/* Child inside Provider will get "Initial Value" */}

</Context.Provider>

<Child2 /> {/* Child outside Provider will get "Default Value" */}

</>

);

}⚝ Try this example on CodeSandbox

The ContextType property on a class component can be assigned a Context object created by React.createContext() method. This property lets you consume the nearest current value of the context using this.context. We can access this.context in any lifecycle method including the render functions also.

Example:

class ContextConsumingInLifeCycle extends React.Component {

static contextType = UserContext;

componentDidMount() {

const user = this.context;

console.log(user); // { name: "Vipin Tak", address: "INDIA", mobile: ""0123456789"" }

}

componentDidUpdate() {

const user = this.context;

/* ... */

}

componentWillUnmount() {

const user = this.context;

/* ... */

}

render() {

const user = this.context;

/* render something based on the value of user */

return null;

}

}The Context API allows data storage and makes it accessible to any child component who want to use it. This is valid whatever level of component graph the children is in.

Example:

const MyContext = React.createContext()

const MyComponent = () => {

const { count, increment } = useContext(MyContext)

return (

<div onClick={increment}>price: {count}</div>

)

}

const App = () => {

const [count, updateCount] = useState(0)

function increment() {

updateCount(count + 1)

}

return (

<MyContext.Provider value={{ count, increment }}>

<div>

<MyComponent />

<MyComponent />

</div>

</MyContext.Provider>

)