An introduction to accessing and serving files with Node.

Here's a quick example of how we might send an HTML response using Node:

function router(request, response) => {

response.writeHead(200, { "content-type", "text/html" });

response.end("<h1>hello</h1>");

});It's quick and easy to send a response body using JS strings. However for more complex response types this can get difficult.

For example we can serve a simple SVG image inline:

response.end(`

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" viewBox="0 0 100 100">

<rect width="50" height="50" x="25" y="25" fill="red" />

</svg>

`);but serving binary file types (like a JPEG image) this way would be difficult. If you open a JPEG in a text editor you'll see a huge blob of incomprehensibly encoded characters. It's easier to store these as separate files and read their content when we need it.

- Clone this repo

- Run

npm installto install the project's dependencies

This project has the nodemon module installed as a devDependency (you can see this in the package.json). This is a useful tool that will watch your files for changes and restart your server automatically when you save.

Open workshop/practice.js in your editor. Run npm run practice in your terminal to make your code auto-restart when you save changes.

Node provides the fs module for working with your computer's file-system. We can import it using Node's require syntax:

const fs = require("fs");fs is an object with lots of useful methods. Right now we want to read the contents of a file, so we'll use the fs.readFile method. It takes a file path as the first argument and a callback function for it to run once the file is available.

const fs = require("fs");

fs.readFile("workshop/test.txt", (error, file) => {

console.log(file);

});Run this and you should see something like <Buffer 53 6f...> logged. This is a chunk of memory representing the contents of the file. If you want to see it represented as a JS string you can pass the file's encoding as the second argument:

const fs = require("fs");

fs.readFile("workshop/test.txt", "utf-8", (error, file) => {

console.log(file);

});This isn't necessary to use the file contents (since Node understands buffers), just to print them in a format we can read.

There are quite a few things that could go wrong when dealing with the file-system, so it's important to make sure we handle errors. Change the file path you're reading to "not-real.txt". Now when you run the script you should see undefined logged.

Since callbacks have no built-in way to handle errors (unlike promises with their .catch method) Node relies on a convention. All callbacks will be called with a possible error as the first argument and the actual thing you want as the second. If there was no error this argument will be null.

So generally you want to handle the error first in your callback, then deal with the "happy case".

fs.readFile("not-real.txt", "utf-8", (error, file) => {

if (error) {

console.log(error);

} else {

console.log(file);

}

});Run this and you should see an error containing "no such file or directory". For an HTTP server you would probably want to send a 404 status code and an error message back to the page.

File paths are actually quite complicated. The one we hard-coded above works on most Unix systems (Mac and Linux) but would probably break on Windows, since that uses backslashes to separate files. Node has built-in helpers to create cross-platform paths.

We can use the path module's path.join() method to join strings together correctly.

const fs = require("fs");

const path = require("path");

fs.readFile(path.join("workshop", "test.txt"), (error, file) => {});There's one more problem: the path we've written is relative to the directory we ran our JS file from. cd into the workshop folder, then run node practice.js. You should see an error logged, because there is no "workshop" directory inside of workshop/.

Node provides a global variable called __dirname (that's two underscores). This will always be the path to the directory the currently executing file is inside. So in this case it will always be stuff/on/your/computer/node-file-server/workshop/. This make it safe to use in our readFile: it will always be correct no matter where we start our program.

fs.readFile(path.join(__dirname, "test.txt"), (error, file) => {});Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (or MIME type) is a standard that determines what format a file is. You've encountered them already in the content-type HTTP header (like "application/json" or "text/html").

MIME types are structured as generic/specific. For example text/plain, text/html and text/css are all kinds of text file, whereas image/png and image/jpeg are kinds of image file.

It's very important to set the content-type header correctly, as web browsers ignore file extensions and rely on this header to parse a file. This means if you serve my-site.com/styles.css with a content-type of text/html the browser may not use it properly.

It's easy to do this manually for one-off files, but if you want to write a generic endpoint that can serve any static file you need to map file extensions to MIME types:

const types = {

html: "text/html",

css: "text/css",

js: "application/javascript",

};

function router(request, response) {

const urlArray = request.url.split("."); // e.g. "/style.css" -> ["/style", "css"]

const extension = urlArray[1]; // e.g. "css"

const type = types[extension]; // e.g. "text/css"

response.writeHead(200, { "content-type": type });

// ...

}- Open

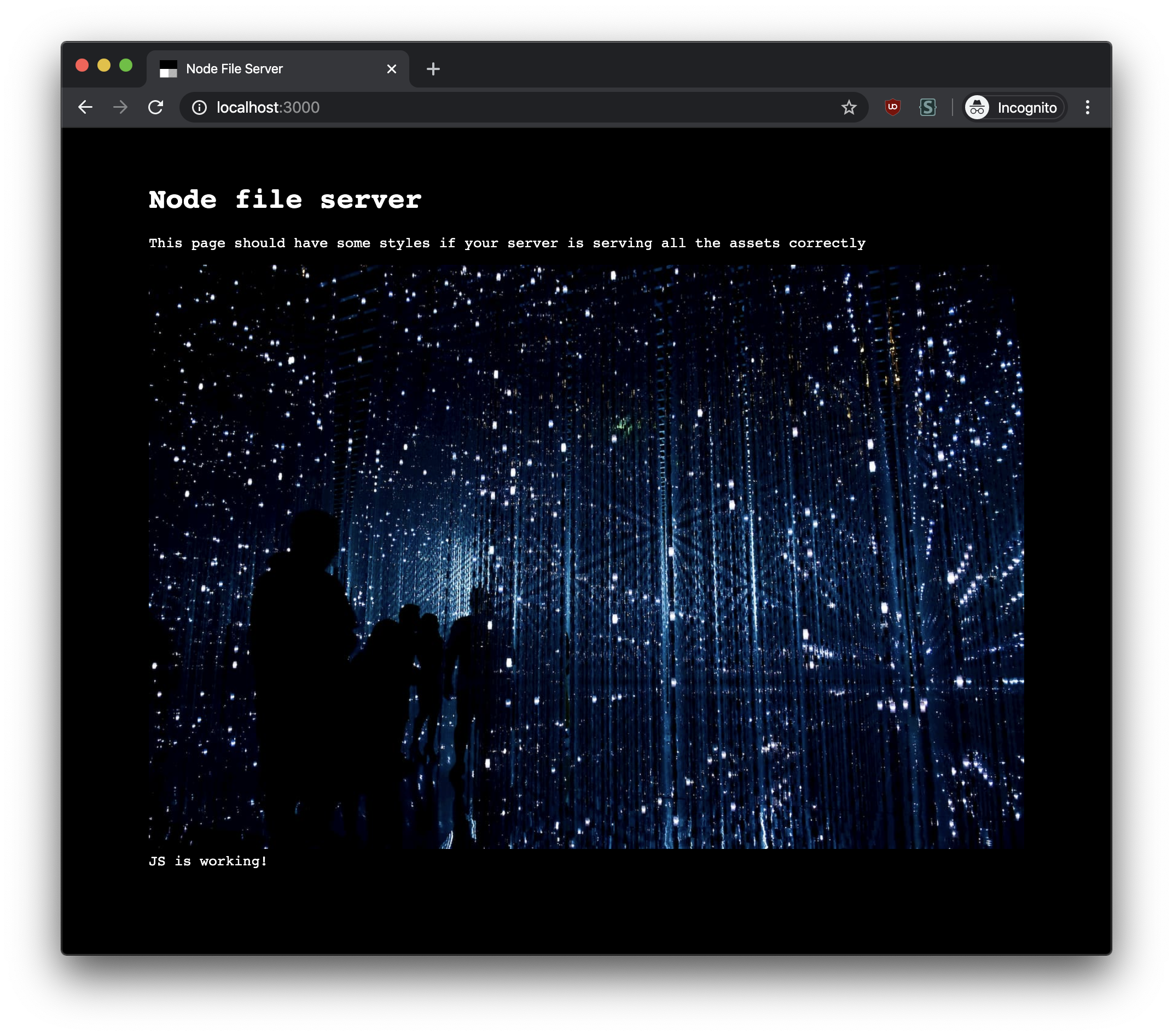

workshop/server.jsin your editor - Run

npm run dev, then openhttp://localhost:3000in your browser - You should see an HTML page loaded, but with no styles

- Check the network tab and you'll see failing requests for

.css,.js,.icoand.jpgfiles

- Check the network tab and you'll see failing requests for

- Edit the

handlers/public.jsto make these requests work- Make sure they have the correct

content-typeheader

- Make sure they have the correct

Hint: take a look at handlers/home.js for a refresher on readFile and paths.