One of the most

| Front Book Cover | Back Book Cover |

|---|---|

| Book Name | Basics of Brain and Computer Interfaces |

| Authors | S.Y.Moradi, M.H.Mohammadi |

| language | Persian |

| Printed in the | IRAN |

| Publisher | ... |

| First Printing Edition | ... |

| Print Length | ... |

| ISBN | 978-600-...-...-. |

- Chapter 1: Basics of Brain and Computer Interfaces

- Chapter 2: Name of sensor technology

- Chapter 3: Bio-non-biological interface

- Chapter 4: BMI / BCI modeling and signal processing

- Chapter 5: Hardware implementation

- Chapter 6: BCI Electrical Stimulation and Rehabilitation Applications

- Chapter 7: Non-invasive communication systems

- Chapter 8: Cognitive and emotional neuroprostheses

- Chapter 9: Organization of research, budget, translation, trade and education issues

Brain-computer communication deals with the creation of communication paths between the brain and external devices. BCI devices can be broadly classified depending on the electrodes' location to detect and measure neurons in the brain: In invasive devices, electrodes are placed on the scalp, and electroencephalography or electrocorticography is used detect neuronal activity. This WTEC study is designed to gather information on the global situation and trends in BCI research and disseminate it to government decision-makers and the research community. This study examines the state of sensor technology. It evaluates biocompatibility, data analysis and modeling, hardware implementation, device engineering, functional electrical stimulation, useful communication devices, and cognitive and emotional weakness in academic and industry research. The jury identified several key trends in evolving BCI research in North America, Europe, and Asia:

- BCI research is widespread around the world, and its size is increasing.

- BCI research is rapidly approaching the level of first-generation medical application; Also, BCI research is expected to accelerate quickly in the non-medical fields of business, particularly in the gaming, automotive, and robotics industries.

- The focus of BCI research around the world is entirely unequal, as non-invasive BCI devices are concentrated almost exclusively in North America; he does. In terms of budget, BCIs and brain-controlled robotics programs have been the hallmark of recent European research and technology development.

Although neural networks are developing many government programs, private resources still significantly impact BCI research in North America. However, small research grants and little technology transfer research have effectively promoted the transition from basic research to prototypes. In Asia, China is investing heavily in life sciences and engineering, and investment in the BCI system and BCI-related research has increased incredibly rapidly.

Japanese universities, research institutes, and laboratories are also increasing their investment in BCI research.

Japan is powerful in pursuing non-medical applications and exploiting its expertise in BCI-controlled robotics.

The jury concluded that there are many opportunities for global collaboration in BCI research and related fields.

| Chapter 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1-1 Introduction | 1-9 Results stated | 1-17 Joint Global Research Opportunities |

| 1-2 Mission: WTEC | 1-10 Executive Summary Theodore W. Berger | 1-18 Highlights of the BCI R&D study in the US and Europe |

| 1-3 Foreword | 1-11 Major Courses in BCI Research | 1-19 Study Highlights: BCI Research and Development in Asia |

| 1-4 Brain Computer Interface Science | 1-12 Scope of BCI research | 1-20 Conclusion |

| 1-5 Related activities in NSF | 1-13 Aggressive versus BCI noninvasive research | 1-21 Opportunities for joint global research |

| 1-6 The Importance of BCI Research and Development to the American Economy and Society | 1-14 BCI Medical Requirement | 1-22 Background |

| 1-7 BCI-related job and training opportunities | 1-15 BCI Research Scope, BCI Non-Medical | 1-23 Methodology |

| 1-8 BCI discussion and innovation discussion and competitiveness | 1-16 Transfer / Trade BCI | 1-24 Overview of the report |

This chapter reviews the sensors used in data collection for Brain-Computer Interface Technology (BCI). For this chapter, we divide sensor technologies into two main categories. First, we discuss "invasive" technologies that involve brain surgeries for implantation, including predominantly multielectrode recordings of microelectrode arrays located in the brain to measure the action potentials of individual cells. This area is the most significant growth for sensor technologies and will be the main focus of this season.

However, we warn that most of this technology is being developed in animal models and has not yet been approved for human use. Also, the measurement of subdural or epidural strips of electrode arrays used to record cortical potential will be somewhat similar to EEG recordings on the skull's surface, as this is currently the most extensive application of these invasive electrodes in humans. (Primarily) Epilepsy surgery. However, this can help increase the growth of other BCI programs. Second, we discuss "non-invasive" technologies, which primarily include multielectrode EEG recording arrays of wet silver (silver) or gold (Au) paste electrodes placed on the surface of the skull to record EEG activity. These electrodes are commercially available from several sources, but surprisingly, limited growth has been observed in this area. We warn that "non-invasive" electrodes are mainly used and may be used aggressively for the scalp in chronic and more advanced BCI technology applications by humans at home or work in the future. The development of other technology The technology in this area will be briefly discussed. We do not discuss other recording electrodes such as EMG electrodes and accompanying electrodes covered in other sources. We do not discuss deep brain stimulation (DBS) technology, which is widely used in patients with movement disorders (Kossof et al. 2004).

However, it must be controlled because chronic implantation of excitation electrodes for DBS is a clinical associate for developing long-term brain electrode technologies and a testing ground for the development of BCI-compatible brain devices (see Chapter 3).

Electrodes enable technologies that encrypt information from the brain by computer algorithms to provide access to and control BCI devices. Without these devices, we would not transmit data from the brain that could be used to control BCI instruments. Likewise, it is often assumed that the technologies around BCI sensors are fully operational, and there is little room for improvement. There is tremendous potential for these devices' growth, and new types of invasive and non-invasive electrode technologies are needed to further the BCI applications. The main challenges are discussed at the end of this chapter.

The purpose of this chapter is to review the current sensor technologies used for BCI offensive and non-invasive approaches across North America, Europe, and Asia. We have visited and interacted with critical laboratories specializing in these fields. Although not entirely comprehensive, this chapter provides an overview of the essential technologies of sensors developed for potential BCI applications.

We look forward to working with Jason J. Bremister, a colleague at the University of Kentucky, to prepare this chapter.

| Chapter 2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2-1 Introduction | 2-6 Silicon-based microelectrodes | 2-11 Non-invasive sensor for BCI |

| 2-2 World overview of BSI sensor | 2-7 Ceramic-based microelectrodes | 2-12 The main challenges for the production of BCI sensors |

| 2-3 Major types of BCI technology sensors | 2-8 Polyamide-based microelectrodes | 2-13 Summary and Conclusion |

| 2-4 Micro-electrode wire type | 2-9 Connectors | 2-14 Reference |

| 2-5 Micro electrodes made of mass | 2-10 ECoG strip electrode |

Brain-computer relationships (BCIs), or brain-system relationships (BMIs), are systems designed to help people with central nervous system disabilities, including the inability to move, communicate, and control independently of the personal environment (Donoghue, 2002; Friehs et al., 2004; Lebedev and Nichols, 2006; Schwartz et al., 2006). Although these similar approaches can enhance normal functioning, this new class of biomedical devices is now thought to be designed to help people with disabilities. Thus, these devices may be useful for patients with various conditions, including spinal cord injury, musculoskeletal disorders, stroke, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or other neuromuscular diseases. The purpose of these devices and the components associated with them is to provide or complement the motor or sensory function that has been lost. The theoretical basis for such devices is our ability to detect neural signals and translate voluntary commands into control signals for external devices such as computers, robotics, or other devices. The acquisition of neural signals has traditionally occurred in the cerebral cortex, and the recording of these signals from implanted electrodes has a relatively long history.

Although several forms of technology are evolving, this chapter will focus exclusively on our current knowledge of the foreign body's response to aggressive technologies. In general, such devices are scarce by the standards of biomedical experiments and are implanted in the cerebral cortex, the most superficial aspect of the mammalian brain. As currently designed, they penetrate a few millimeters, depending on the target area and species. They contain several recording or excitation sites located in one or more penetrating shafts, including conductive ceramics, metals, or polymers, and have at least one insulating material. At present, such devices are connected to insulated wires that protrude from the skull and lead to external amplifiers and other devices, which are sizeable and not very reliable.

Because of their design nature, recorders are often referred to as "penetrating electrode arrays."

To date, CNS recorders have taught us a great deal about the functional organization and neurophysiological underpinnings of the mammalian cortex and other areas of the brain. It becomes quality. The lives of people with CNS-related disabilities (Lebedev and Nichols, 2006; Schwartz et al., 2006). The future economic impact of this technology seems equally remarkable. Along with other emerging technologies, we find ourselves on the verge of understanding one of the most complex and sophisticated systems the human brain has ever studied. What has been shown is that neural signals can be recorded by several different technologies in different species for periods, from months to wells for more than a year. With direct reference to BCI or BMI technology, neural activity can be interpreted and used to control a computer or robot, or prosthetic device.

By exploring and proving the solid principle for various BCI and BMI programs, some focus has shifted to understanding how to maintain the continuous and long-term performance of implanted devices. Even if current plans typically perform as intended in short-term studies and projects, the major limitation of our current state of technology is the inconsistent performance of chronic or long-term goals that limit this promising technology (Polikov et al., 2005; Schwartz et al., 2006).

Although it is believed that brain tissue response to implanted electrode arrays is a specific construct that ensures that the recording function is not inconsistent; Therefore, until the mechanisms underlying the loss of performance are understood, it seems unlikely that we will develop rational strategies to improve their usefulness.

This chapter first discusses what is challenging to understand and lays the foundation for standard terms. It then provides evidence that invasive electrodes can act over long periods to demonstrate the concept that this new class of biomedical device is currently thought to be biocompatible. This current situation then examines the understanding of what happens after electrode implantation in mammalian brains and tries to identify gaps in our knowledge, if possible, to clarify what still needs to be done. The conclusion is by discussing the various strategies being developed to modify the biotic-abiotic interface to integrate brain tissue better and achieve superior device function. We warn that most technologies focused on enhancing device performance, as promising as it may seem, are still under development and have not been replicated enough in most parts to understand our ultimate understanding of its maximum impact.

With all the signs, a full understanding of what needs to be done to different interface hardware with various potential neural targets continually is still a long way off. It is now a significant obstacle to understanding the science responsible for the loss of performance. Without understanding the increased and targeted budget for increasing the number of researchers working in this field, this understanding is unlikely to happen shortly. The breadth and depth of science must advance, as has happened in cochlear implantation, so that this challenge shifts from a lack of scientific engineering knowledge.

| Chapter 3 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 3-1 Introduction | 3-3 Key Challenge: Consistent, long-lasting and efficient integration | 3-5 Reference |

| 3-2 An overview of the world of BCI biological relationships | 3-4 Summary and Conclusion |

Due to the large differences in biophysical properties between the multi-electrode array and the EEG / ECoG recording, this report deals with them separately. The signal processing methods required for spatial resolution, feature extraction, and intent interpretation depend on the choice of the recording method, including electroencephalography (EEG), electrocorticography (ECoG), local field potentials (LFP), and possible single neuron recordings (units).

Brain system relationships (BMI) are significantly different from BCIs, although they have been proposed to solve the same problem: translating a person's goal into robotic commands. BCI works with macroscopic brain activity (mainly EEG) that is found to be related to behavior but is scattered and indistinct. Using existing knowledge of EEG research and machine learning techniques, BCI is now thriving and ready for patients' use (see site reports in Appendices B and C). Still, their application in the full game is the functions required in the unlimited interaction of a subject with a limited environment. BMIs, on the other hand, examine the brain at many different levels of abstraction (microscopically as spikes and mesoscopically as local potentials, or LFPs) and thus offer potentially better performance at a more demanding cost.

Functional organization of the brain at these different levels, e.g., neural code, neural assembly, and its cytoarchitecture. BCIs are likely to be confused with BMI when macroscopic information is incorporated. Due to this better integration of BMI with brain signals, more in-depth knowledge of neurophysiology is required to perform this research type than its BCI counterpart. Larger multidisciplinary teams are needed to advance research in this area. All successful groups in the United States have a combination of specialization in fundamental neuroscience (electrophysiology), computational neuroscience, signal processing, and advanced electronic and computer systems; And all this may not be enough yet!

| Chapter 4 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 4-1 Introduction | 4-6 EEG / ECoG recordings | 4-11 Feature translation |

| 4-2 Multi-piece array techniques | 4-7 Spontaneous ECoG decoding for Intent | 4-12 Online evaluation |

| 4-3 Binned data models | 4-8 Extract time and domain attributes | 4-13 Summary and Conclusion |

| 4-4 Spike - train methods (point process) | 4-9 Extract frequency-amplitude attribute | 4-14 Reference |

| 4-5 Relationships between spike trains and local field potentials | 4-10 Space filter |

The paralysis that negatively affects millions of people worldwide has many causes, including trauma, stroke, infection, and autoimmune diseases. Direct damage can occur to the brain, spinal cord, spinal nerves, or the muscles themselves. In general, "paralysis" refers to the severe or complete loss of motor function, while "Paris" refers to relatively minor damage. Severe paralysis is a significant problem, not only because patients do not lose the ability to lead an everyday life but also because of the patient's high cost of caring. For example, patients with tetraplegic spinal cord injuries lose almost all of their voluntary motor function under the neck. Still, they also lose the sensation of touch, pain, temperature, and posture. Severe amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is even worse, so patients can lose all motor function in their body.

Fortunately, recent publicity about spinal cord injury (SCI) has helped find a cure for SCI and other crippling diseases. Over the past 20 years, most research has focused on cell biology approaches that hope to generate neurotransmitters, transformed somatic cells, or embryonic stem cells to stimulate damaged nerve fibers to grow beyond the site of spinal cord injury and wish to make synaptic contact Incorrect motor neurons. Although such an approach may one day provide the best treatment for paralysis, this research area is only in its infancy. Given the current progress and the number of fractures required, it will take years for a real cure to be available; Therefore, these methods may not be useful for SCI patients in the short term.

| Chapter 5 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 5-1 Introduction: Restoration of movement in paralyzed patients | 5-7 Destroy key capabilities for controlled ROBOTICS from the brain | 5-13 Requires Biomimetic arm / foot prosthesis robots with high degree of freedom (DOF) |

| 5-2 EEG-based computer and brain interface | 5-8 Extract engine commands from monkey brains | 5-14 ROBOT research at SCUOLA SUPERIORE sant |

| 5-3 Direct relationship between brain and computer | 5-9 Biofeedback coding robot arm change | 5-15 The reason for making Biomimetic hand prostheses |

| 5-4 Different approaches to BCI research worldwide | 5-10 Brain control multi-output functions | 5-16 Research approach to biotechnology in SSA |

| 5-5 Recording, extracting and decoding neural motor commands | 5-11 Need for sensor feedback to facilitate control of robotic movements | 5-17 Use of direct BCIs to control biomimetic robotic prostheses |

| 5-6 Use of multivariate regression analysis (MRA) to predict organ movement kinematics | 5-12 Need to control more degrees of freedom in robots controlled from the brain | 5-18 Reference |

Functional electrical stimulation (FES) is the controlled use of the electrical current in peripheral nerves to produce beneficial muscle contractions in people with nervous system dysfunction. Over the past few decades, many different FES technology applications have been developed (Figure 6.1), and these can be divided into two main categories. The first category includes systems that save lives by restoring the essential functions of independence. The most well-known and widespread example of commercial FES technology is the pacemaker, which is used to reliably activate the heart muscle in people with impaired cardiac circulation. Other commercial technologies, such as the Vocare® system, are used to restore bladder function after spinal cord injury. FES diaphragm systems have the potential to eliminate the need for ventilation in severely paralyzed individuals. Also, nerve stimulation techniques that coordinate breathing and the swallowing reflex pathways are used to treat sleep apnea or facilitate swallowing after a stroke...

| Chapter 6 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 6-1 Overview of functional electrical stimulation | 6-4 Application areas of BCI controlled FCS systems | 6-7 Potential therapeutic applications |

| 6-2 BCI IT applications worldwide | 6-5 When additional command options are required | 6-8 Discussion about performance |

| 6-3 How different types of BCI command symbols can be applied to FES | 6-6 Better production and more natural control | 6-9 Reference |

Conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), stroke, and severe brain or spinal cord injury can control the nerve pathways that control the muscles or disrupt the forces themselves. People who are severely affected may lose voluntary muscle control, including eye movements and breathing, and maybe wholly closed to their body, unable to communicate at all. Various studies over the past 15 years have shown that a registered scalp electroencephalogram (EEG) can be used as a basis for a brain-computer interface (Wolpaw et al., 2002). BCI can provide an alternative method of communication and control for people who have been severely injured.

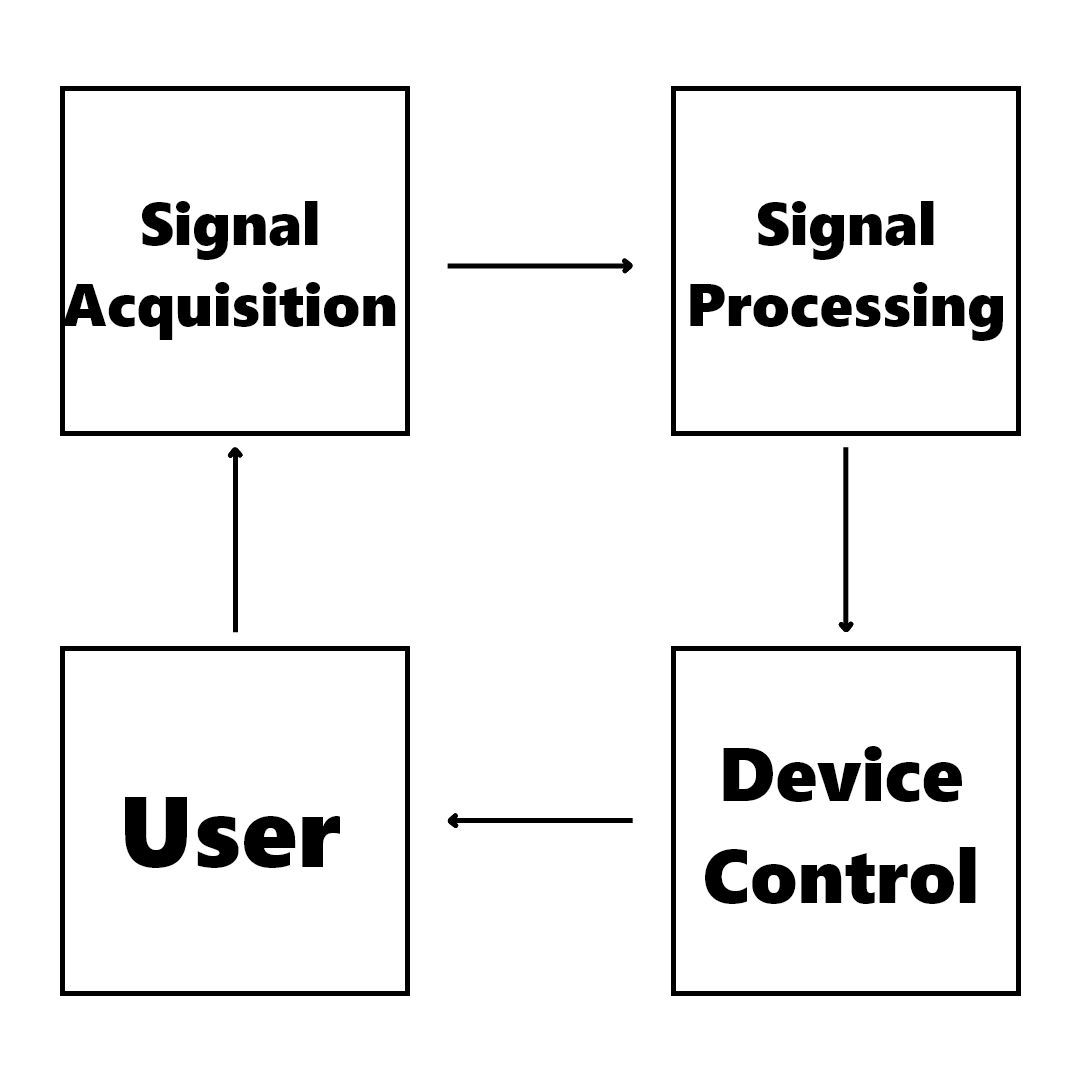

The BCI system consists of sensors that extract neural activity, signal processing, and a translation algorithm that generates device commands to work with an external device (Wolpaw et al., 2002). The loop is completed by external device feedback to the BCI system user. These critical elements of a BCI communication system are shown in Figure 7.1. As shown in the figure, there is a flow of information through each component that eventually returns to the user. An efficient BCI system is a closed-loop, real-time system. In the case of BCI communication systems, the external device serves to communicate with the user.

There are several BCI communication systems designed to prove the principle. These are based on a variety of neural properties such as slow cortical potential (Birbaumer et al., 1999), motor potentials (Mason et al., 2004), coordination, and event-related coordination (Pfurtscheller et al., 1993; Wolpaw et al., 1991). Sustainable (Jones et al., 2003) and the potentials of P300 (Farrell and Duncin, 1988). These systems typically use surface-recorded EEG. Non-invasive EEG recordings are a safe alternative to invasive procedures that may provide useful BCI communication devices for people with disabilities.

Essential components of a BCI communication system. Signals flow from the user to receive the signal, process the signal, control the device, and then return it to the user. Efficient operation requires the completion of this process in real-time.

| Chapter 7 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 7-1 Introduction | 7-5 Stable and fantastic selected pots | 7-9 License for PRACTICAL communication systems |

| 7-2 Slow heavy trading | 7-6 P300 evoked potentials | 7-10 Summary and Conclusion |

| 7-3 Motor potentials | 7-7 Conformity | 7-11 Reference |

| 7-4 Event-related synchronizations and programming | 7-8 Online evaluations |

Previous chapters describe BCI programs that restore motor or communication functions in the brain for patients paralyzed by spinal cord injury or muscular dystrophy. These BCIs extract electrophysiological signals from healthy motor cortices and process them into control commands for computers, robotic machines, or communication devices. The brain can be directly damaged by genetic disorders or injuries caused by stroke or disease. Brain damage can lead to numerous cognitive impairments, including memory loss, mood or personality changes, and even behavioral changes that include motor or communication function. This chapter presents some of the neuroprosthetic developments that aim to address such cognitive or emotional dysfunction.

A big challenge for cognitive prostheses is that the neural code for their intended tasks is not yet exact. In contrast to motor cortex signals that regulate neural activity in terms of motion, velocity, and even force to be decoded (Chapter 5), or large EEG components that are easily scalable (Chapter 7), coding of cognitive processes continues. Decoding the following cognitive prostheses has developed innovative strategies for overcoming or bypassing this barrier to using higher mental functions for BCI programs. The prostheses' main feature is that they extract cognitive status information from neural signals to provide appropriate feedback to the user.

| Chapter 8 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 8-1 Introduction | 8-5 Proof of concept in hippocampal incision | 8-9 Neurofeedback for ADHD |

| 8-2 VOLITIONAL PROVISIONS | 8-6 Hippocampal neuroprosthesis for animal behavior | 8-10 Neurofeedback to control emotions and social personality disorders |

| 8-3 Emotional computers and robots | 8-7 Neurofeedback | 8-11 Summary and Conclusion |

| 8-4 Memorable features | 8-8 Neurofeedback for epilepsy | 8-12 Reference |

| Chapter 9 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 9-1 Organization and research and investigation of BCI | 9-2 Funding and financing mechanisms | 9-3 Transfer and trade |

| 9-4 Reference |

I am Biomedical Engineer from University of Isfahan. My research interests is Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation, Neuroscience, Brain Mapping & Connectivity, Biomedical AI & IOT, Biosignal Processing.

- Brain stimulation techniques such as tDCS, tACS, tRNS, TMS, Theta-Burst Stimulation (TBS) and Magnetic Seizure Therapy (MST)

- Sleep, Plasticity, Perception, Vision, Navigation

- Q/EEG Decoding; Source Localization; Beamforming; Blind source separation

- Causal Inference; Big Data; Unsupervised & Online learning; Expert System

- Chaos and Fractal Theory

🌐 𝐏𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐏𝐚𝐠𝐞 "𝐒𝐞𝐲𝐞𝐝 𝐘𝐚𝐡𝐲𝐚 𝐌𝐨𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢" 👉 symoradi.website2.me

📧 𝐄𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐥: s.yahyamoradi@yahoo.com

============================================================================

Iam currently a Final-year BS.c student at the Department of Computer Engineering, Islamic Azad University, Najafabad Branch (IAUN) (Rank in CWUR) where I am a member of the Bioinformatics Laboratory (BL), advised by Prof. Mohammad Naderi Dehkordi. my research involves machine vision, deep learning, and neural networks. where I will complete my thesis on Accurate and Early Identification of Diabetes and it's Affecting Factors.

Prior to BL, I finished my Diploma - Mathematics and Physics in Sheikh Ansari Highschool, in September 2015. I tried to use my Diploma to build a solid bedrock for my future research. So in addition to taking many optional bachelor-level courses on math and computer science. I spent 6 months as an intern Programmer at the "CoTech" in Isfahan.

- Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning

- Optimization Algorithm, Neural & NeuroFuzzy Network

- Computer Vision, Signal and Image Processing

🌐 𝐏𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐏𝐚𝐠𝐞 "𝐌𝐨𝐡𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐝 𝐇𝐨𝐬𝐬𝐞𝐢𝐧 𝐌𝐨𝐡𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐝𝐢" 👉 mohammadimh76.github.io

📧 𝐄𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐥: m.h.mohammadimir2017@gmail.com

👇Click on the link below to see the E-Book Demo!👇😉