A Distributed Tracing API for Swift.

This is a collection of Swift libraries enabling the instrumentation of server side applications using tools such as tracers. Our goal is to provide a common foundation that allows to freely choose how to instrument systems with minimal changes to your actual code.

While Swift Distributed Tracing allows building all kinds of instruments, which can co-exist in applications transparently, its primary use is instrumenting multi-threaded and distributed systems with Distributed Traces.

This project uses the context progagation types defined independently in:

- 🧳 swift-distributed-tracing-baggage --

LoggingContext(Swift Log dependency) - 🧳 swift-distributed-tracing-baggage-core -- defining

Baggage(zero dependencies)

⚠️ ⚠️ ⚠️ We anticipate the upcoming Swift Concurrency features to have significant impact on the usage of these APIs, if task-local values (proposal coming soon) are accepted into the language.

As such, we advice to adopt these APIs carefully, and offer them optionally, i.e. provide defaulted values for context parameters such that users do not necessarily have to use them – because the upcoming Swift Concurrency story should enable APIs to gain automatic context propagation using task locals (if the proposal were to be accepted).

At this point in time we would like to focus on Tracer implementations, final API polish and adoption in "glue" libraries between services, such as AsyncHTTPClient, gRPC and similar APIs.

⚠️ ⚠️ ⚠️

- Compatibility

- Getting Started

- In-Depth Guide

- In-Depth Guide for Application Developers

- In-Depth Guide for: Library/Framework developers

- In-Depth Guide for: Instrument developers

- Contributing

This project is designed in a very open and extensible manner, such that various instrumentation and tracing systems can be built on top of it.

The purpose of the tracing package is to serve as common API for all tracer and instrumentation implementations. Thanks to this, libraries may only need to be instrumented once, and then be used with any tracer which conforms to this API.

Compatible Tracer implementations:

| Library | Status | Description |

|---|---|---|

| @slashmo / Swift Jaeger Client | Complete | Thrift and JSON formats, supported; including Zipkin format. |

| @pokrywka / AWS xRay SDK Swift | Complete (?) | ... |

| OpenTelemetry | TODO | ... |

| Your library? | ... | Get in touch! |

If you know of any other library please send in a pull request to add it to the list, thank you!

As this API package was just released, no projects have yet fully adopted it, the following table for not serves as reference to prior work in adopting tracing work. As projects move to adopt tracing completely, the table will be used to track adoption phases of the various libraries.

| Library | Integrates | Status |

|---|---|---|

| AsyncHTTPClient | Tracing | Old* Proof of Concept PR |

| Swift gRPC | Tracing | Old* Proof of Concept PR |

| Swift AWS Lambda Runtime | Tracing | Old* Proof of Concept PR |

| Swift NIO | Baggage | Old* Proof of Concept PR |

| RediStack (Redis) | Tracing | Signalled intent to adopt tracing. |

| Soto AWS Client | Tracing | Signalled intent to adopt tracing. |

| Your library? | ... | Get in touch! |

*Note that this package was initially developed as a Google Summer of Code project, during which a number of Proof of Concept PR were opened to a number of projects.These projects are likely to adopt the, now official, Swift Distributed Tracing package in the shape as previewed in those PRs, however they will need updating. Please give the library developers time to adopt the new APIs (or help them by submitting a PR doing so!).

If you know of any other library please send in a pull request to add it to the list, thank you!

In this short getting started example, we'll go through bootstrapping, immediately benefiting from tracing, and instrumenting our own synchronous and asynchronous APIs. The following sections will explain all the pieces of the API in more depth. When in doubt, you may want to refer to the OpenTelemetry, Zipkin, or Jaeger documentations because all the concepts for different tracers are quite similar.

In order to use tracing you will need to bootstrap a tracing backend (available backends).

When developing an application locate the specific tracer library you would like to use and add it as an dependency directly:

.package(url: "<https://example.com/some-awesome-tracer-backend.git", from: "..."),Alternatively, or when developing a library/framework, you should not depend on a specific tracer, and instead only depend on the tracing package directly, by adding the following to your Package.swift:

.package(url: "https://github.com/apple/swift-distributed-tracing.git", from: "0.1.0"),

To your main target, add a dependency on Tracing library and the instrument you want to use:

.target(

name: "MyApplication",

dependencies: [

"Tracing",

"<AwesomeTracing>", // the specific tracer

]

),Then (in an application, libraries should never invoke bootstrap), you will want to bootstrap the specific tracer you want to use in your application. A Tracer is a type of Instrument and can be offered used to globally bootstrap the tracing system, like this:

import Tracing // the tracing API

import AwesomeTracing // the specific tracer

InstrumentationSystem.bootstrap(AwesomeTracing())If you don't bootstrap (or other instrument) the default no-op tracer is used, which will result in no trace data being collected.

Automatically reported spans: When using an already instrumented library, e.g. an HTTP Server which automatically emits spans internally, this is all you have to do to enable tracing. It should now automatically record and emit spans using your configured backend.

Using baggage and logging context: The primary transport type for tracing metadata is called Baggage, and the primary type used to pass around baggage context and loggers is LoggingContext. Logging context combines baggage context values with a smart Logger that automatically includes any baggage values ("trace metadata") when it is used for logging. For example, when using an instrumented HTTP server, the API could look like this:

SomeHTTPLibrary.handle { (request, context) in

context.logger.info("Wow, tracing!") // automatically includes tracing metadata such as "trace-id"

return try doSomething(request context: context)

}In this snippet, we use the context logger to log a very useful message. However it is even more useful than it seems at first sight: if a tracer was installed and extracted tracing information from the incoming request, it would automatically log our message with the trace information, allowing us to co-relate all log statements made during handling of this specific request:

05:46:38 example-trace-id=1111-23-1234556 info: Wow tracing!

05:46:38 example-trace-id=9999-22-9879797 info: Wow tracing!

05:46:38 example-trace-id=9999-22-9879797 user=Alice info: doSomething() for user Alice

05:46:38 example-trace-id=1111-23-1234556 user=Charlie info: doSomething() for user Charlie

05:46:38 example-trace-id=1111-23-1234556 user=Charlie error: doSomething() could not complete request!

05:46:38 example-trace-id=9999-22-9879797 user=alice info: doSomething() completed

Thanks to tracing, and trace identifiers, even if not using tracing visualization libraries, we can immediately co-relate log statements and know that the request 1111-23-1234556 has failed. Since our application can also add values to the context, we can quickly notice that the error seems to occur for the user Charlie and not for user Alice. Perhaps the user Charlie has exceeded some quotas, does not have permissions or we have a bug in parsing names that include the letter h? We don't know yet, but thanks to tracing we can much quicker begin our investigation.

Passing context to client libraries: When using client libraries that support distributed tracing, they will accept a Baggage.LoggingContext type as their last parameter in many calls.

When using client libraries that support distributed tracing, they will accept a Baggage.LoggingContext type as their last parameter in many calls. Please refer to Context argument naming/positioning in the Context propagation section of this readme to learn more about how to properly pass context values around.

Adding a span to synchronous functions can be achieved like this:

func handleRequest(_ op: String, context: LoggingContext) -> String {

let tracer = InstrumentationSystem.tracer

let span = tracer.startSpan(operationName: "handleRequest(\(name))", context: context)

defer { span.end() }

return "done:\(op)"

}Throwing can be handled by either recording errors manually into a span by calling span.recordError(error:), or by wrapping a potentially throwing operation using the withSpan(operation:context:body:) function, which automatically records any thrown error and ends the span at the end of the body closure scope:

func handleRequest(_ op: String, context: LoggingContext) -> String {

return try InstrumentationSystem.tracer

.withSpan(operationName: "handleRequest(\(name))", context: context) {

return try dangerousOperation()

}

}If this function were asynchronous, and returning a Swift NIO EventLoopFuture,

we need to end the span when the future completes. We can do so in its onComplete:

func handleRequest(_ op: String, context: LoggingContext) -> EventLoopFuture<String> {

let tracer = InstrumentationSystem.tracer

let span = tracer.startSpan(operationName: "handleRequest(\(name))", context: context)

let future: EventLoopFuture<String> = someOperation(op)

future.whenComplete { _ in

span.end() // oh no, ignored errors!

}

return future

}This is better, however we ignored the possibility that the future perhaps has failed. If this happens, we would like to report the span as errored because then it will show up as such in tracing backends and we can then easily search for failed operations etc.

To do this within the future we could manually invoke the span.recordError API before ending the span like this:

func handleRequest(_ op: String, context: LoggingContext) -> EventLoopFuture<String> {

let tracer = InstrumentationSystem.tracer

let span = tracer.startSpan(operationName: "handleRequest(\(name))", context: context)

let future: EventLoopFuture<String> = someOperation(op)

future.whenComplete { result in

switch result {

case .failure(let error): span.recordError(error)

case .success(let value): // ... record additional *attributes* into the span

}

span.end()

}

return future

}While this is verbose, this is only the low-level building blocks that this library provides, higher level helper utilities can be

Eventually convenience wrappers will be provided, automatically wrapping future types etc. We welcome such contributions, but likely they should live in

swift-distributed-tracing-extras.

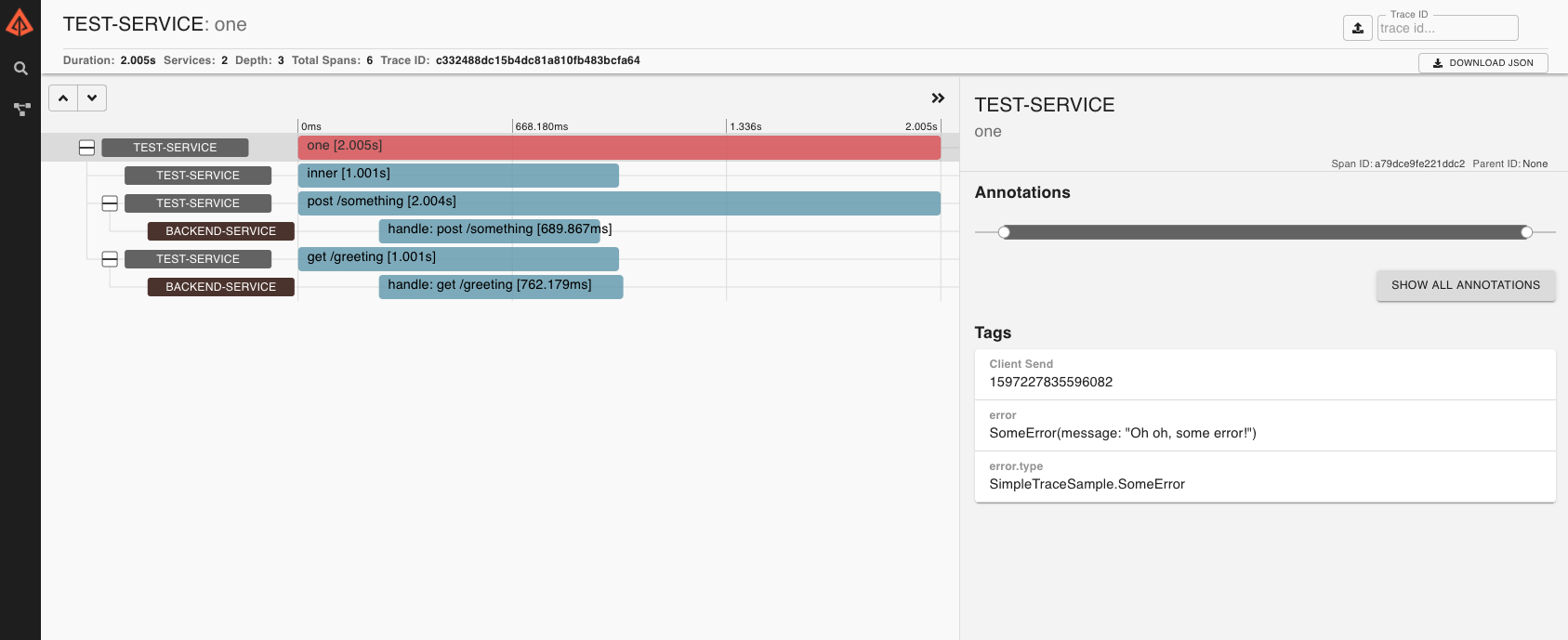

Once a system, or multiple systems have been instrumented, a Tracer been selected and your application runs and emits some trace information, you will be able to inspect how your application is behaving by looking at one of the various trace UIs, such as e.g. Zipkin:

It sometimes is easier to grasp the usage of tracing by looking at a "real" application - which is why we have implemented an example application, spanning multiple nodes and using various databases - tracing through all of them. You can view the example application here: slashmo/swift-tracing-examples.

⚠️ This section refers to in-development upcoming Swift Concurrency features and can be tried out using nightly snapshots of the Swift toolchain.

With Swift's ongoing work towards asynchronous functions, actors, and tasks, tracing in Swift will become more pleasant than it is today.

Firstly, a lot of the callback heavy code will be folded into normal control flow, which is easy and correct to integrate with tracing like this:

func perform(context: LoggingContext) async -> String {

let span = InstrumentationSystem.tracer.startSpan(operationName: #function, context: context)

defer { span.end() }

return await someWork()

}When instrumenting server applications there are typically three parties involved:

- Application developers creating server-side applications

- Library/Framework developers providing building blocks to create these applications

- Instrument developers providing tools to collect distributed metadata about your application

For applications to be instrumented correctly these three parts have to play along nicely.

As an end-user building server applications you get to choose what instruments to use to instrument your system. Here's all the steps you need to take to get up and running:

Add a package dependency for this repository in your Package.swift file, and one for the specific instrument you want

to use, in this case FancyInstrument:

.package(url: "https://github.com/apple/swift-distributed-tracing.git", .branch("main")),

.package(url: "<https://repo-of-fancy-instrument.git>", from: "<4.2.0>"),To your main target, add a dependency on the Instrumentation library and the instrument you want to use:

.target(

name: "MyApplication",

dependencies: [

"FancyInstrument"

]

),Instead of providing each instrumented library with a specific instrument explicitly, you bootstrap the

InstrumentationSystem which acts as a singleton that libraries/frameworks access when calling out to the configured

Instrument:

InstrumentationSystem.bootstrap(FancyInstrument())Swift offers developers a suite of observability libraries: logging, metrics and tracing. Each of those systems offers a bootstrap function. It is useful to stick to a recommended boot order in order to achieve predictable initialization of applications and sub-systems.

Specifically, it is recommended to bootstrap systems in the following order:

- Swift Log's

LoggingSystem - Swift Metrics'

MetricsSystem - Swift Tracing's

InstrumentationSystem - Finally, any other parts of your application

This is because tracing systems may attempt to emit metrics about their status etc.

It is important to note that InstrumentationSystem.bootstrap(_: Instrument) must only be called once. In case you

want to bootstrap the system to use multiple instruments, you group them in a MultiplexInstrument first, which you

then pass along to the bootstrap method like this:

InstrumentationSystem.bootstrap(MultiplexInstrument([FancyInstrument(), OtherFancyInstrument()]))MultiplexInstrument will then call out to each instrument it has been initialized with.

LoggingContextnaming has been carefully selected and it reflects the type's purpose and utility: It binds a Swift LogLoggerwith an associated distributed tracing Baggage.It also is used for tracing, by tracers reaching in to read or modify the carried baggage.

For instrumentation and tracing to work, certain pieces of metadata (usually in the form of identifiers), must be carried throughout the entire system–including across process and service boundaries. Because of that, it's essential for a context object to be passed around your application and the libraries/frameworks you depend on, but also carried over asynchronous boundaries like an HTTP call to another service of your app.

LoggingContext should always be passed around explicitly.

Libraries which support tracing are expected to accept a LoggingContext parameter, which can be passed through the entire application. Make sure to always pass along the context that's previously handed to you. E.g., when making an HTTP request using AsyncHTTPClient in a NIO handler, you can use the ChannelHandlerContexts baggage property to access the LoggingContext.

💡 This general style recommendation has been ironed out together with the Swift standard library, core team, the SSWG as well as members of the community. Please respect these recommendations when designing APIs such that all APIs are able to "feel the same" yielding a great user experience for our end users ❤️

It is possible that the ongoing Swift Concurrency efforts, and "Task Local" values will resolve this explicit context passing problem, however until these arrive in the language, please adopt the "context is the last parameter" style as outlined here.

Propagating baggage context through your system is to be done explicitly, meaning as a parameter in function calls, following the "flow" of execution.

When passing baggage context explicitly we strongly suggest sticking to the following style guideline:

- Assuming the general parameter ordering of Swift function is as follows (except DSL exceptions):

- Required non-function parameters (e.g.

(url: String)), - Defaulted non-function parameters (e.g.

(mode: Mode = .default)), - Required function parameters, including required trailing closures (e.g.

(onNext elementHandler: (Value) -> ())), - Defaulted function parameters, including optional trailing closures (e.g.

(onComplete completionHandler: (Reason) -> ()) = { _ in }).

- Required non-function parameters (e.g.

- Logging Context should be passed as the last parameter in the required non-function parameters group in a function declaration.

This way when reading the call side, users of these APIs can learn to "ignore" or "skim over" the context parameter and the method signature remains human-readable and “Swifty”.

Examples:

func request(_ url: URL,context: LoggingContext), which may be called ashttpClient.request(url, context: context)func handle(_ request: RequestObject,context: LoggingContext)- if a "framework context" exists and carries the baggage context already, it is permitted to pass that context together with the baggage;

- it is strongly recommended to store the baggage context as

baggageproperty ofFrameworkContext, and conformFrameworkContexttoLoggingContextin such cases, in order to avoid the confusing spelling ofcontext.context, and favoring the self-explanatorycontext.baggagespelling when the baggage is contained in a framework context object.

func receiveMessage(_ message: Message, context: FrameworkContext)func handle(element: Element,context: LoggingContext, settings: Settings? = nil)- before any defaulted non-function parameters

func handle(element: Element,context: LoggingContext, settings: Settings? = nil, onComplete: () -> ())- before defaulted parameters, which themselfes are before required function parameters

func handle(element: Element,context: LoggingContext, onError: (Error) -> (), onComplete: (() -> ())? = nil)

In case there are multiple "framework-ish" parameters, such as passing a NIO EventLoop or similar, we suggest:

func perform(_ work: Work, for user: User,frameworkThing: Thing, eventLoop: NIO.EventLoop,context: LoggingContext)- pass the baggage as last of such non-domain specific parameters as it will be by far more omnipresent than any specific framework parameter - as it is expected that any framework should be accepting a context if it can do so. While not all libraries are necessarily going to be implemented using the same frameworks.

We feel it is important to preserve Swift's human-readable nature of function definitions. In other words, we intend to keep the read-out-loud phrasing of methods to remain "request that URL (ignore reading out loud the context parameter)" rather than "request (ignore this context parameter when reading) that URL".

Generally libraries should favor accepting the general LoggingContext type, and not attempt to wrap it, as it will result in difficult to compose APIs between multiple libraries. Because end users are likely going to be combining various libraries in a single application, it is important that they can "just pass along" the same context object through all APIs, regardless which other library they are calling into.

Frameworks may need to be more opinionated here, and e.g. already have some form of "per request context" contextual object which they will conform to LoggingContext. Within such framework it is fine and expected to accept and pass the explicit SomeFrameworkContext, however when designing APIs which may be called by other libraries, such framework should be able to accept a generic LoggingContext rather than its own specific type.

When adapting an existing library/framework to support LoggingContext and it already has a "framework context" which is expected to be passed through "everywhere", we suggest to follow these guidelines for adopting LoggingContext:

- Add a

Baggageas a property calledbaggageto your owncontexttype, so that the call side for your users becomescontext.baggage(rather than the confusingcontext.context) - If you cannot or it would not make sense to carry baggage inside your framework's context object, pass (and accept (!)) the

LoggingContextin your framework functions like follows:

- if they take no framework context, accept a

context: LoggingContextwhich is the same guideline as for all other cases - if they already must take a context object and you are out of words (or your API already accepts your framework context as "context"), pass the baggage as last parameter (see above) yet call the parameter

baggageto disambiguate yourcontextobject from thebaggagecontext object.

Examples:

Lamda.Contextmay containbaggageand aloggerand should be able to conform toLoggingContext- passing context to a

Lambda.Contextunaware library becomes:http.request(url: "...", context: context).

- passing context to a

ChannelHandlerContextoffers a way to set/get baggage on the underlying channel viacontext.baggage = ...- this context is not passed outside a handler, but within it may be passed as is, and the baggage may be accessed on it directly through it.

- Example: apple/swift-nio#1574

Generally application developers should not create new context objects, but rather keep passing on a context value that they were given by e.g. the web framework invoking the their code.

If really necessary, or for the purposes of testing, one can create a baggage or context using one of the two factory functions:

DefaultLoggingContext.topLevel(logger:)orBaggage.topLevel- which creates an empty context/baggage, without any values. It should not be used too frequently, and as the name implies in applications it only should be used on the "top level" of the application, or at the beginning of a contextless (e.g. timer triggered) event processing.DefaultLoggingContext.TODO(logger:reason:)orBaggage.TODO- which should be used to mark a parameter where "before this code goes into production, a real context should be passed instead." An application can be run with-DBAGGAGE_CRASH_TODOSto cause the application to crash whenever a TODO context is still in use somewhere, making it easy to diagnose and avoid breaking context propagation by accidentally leaving in aTODOcontext in production.

Please refer to the respective functions documentation for details.

If using a framework which itself has a "...Context" object you may want to inspect it for similar factory functions, as LoggingContext is a protocol, that may be conformed to by frameworks to provide a smoother user experience.

The primary purpose of this API is to start and end so-called Span types.

Spans form hierarchies with their parent spans, and end up being visualized using various tools, usually in a format similar to gant charts. So for example, if we had multiple operations that compose making dinner, they would be modelled as child spans of a main makeDinner span. Any sub tasks are again modelled as child spans of any given operation, and so on, resulting in a trace view similar to:

>-o-o-o----- makeDinner ----------------o---------------x [15s]

\-|-|- chopVegetables--------x | [2s]

| | \- chop -x | | [1s]

| | \--- chop -x | [1s]

\-|- marinateMeat -----------x | [3s]

\- preheatOven -----------------x | [10s]

\--cook---------x [5s]

The above trace is achieved by starting and ending spans in all the mentioned functions, for example, like this:

let tracer: Tracer

func makeDinner(context: LoggingContext) async throws -> Meal {

tracer.withSpan(operationName: "makeDinner", context) {

let veggiesFuture = try chopVegetables(context: span.context)

let meatFuture = marinateMeat(context: span.context)

let ovenFuture = try preheatOven(temperature: 350, context: span.context)

...

return cook(veggies, meat, oven)

}

}❗️ It is tremendously important to always

end()a startedSpan! make sure to end any started span on every code path, including error pathsFailing to do so is an error, and a tracer may decide to either crash the application or log warnings when an not-ended span is deinitialized.

When hitting boundaries like an outgoing HTTP request you call out to the configured instrument(s):

An HTTP client e.g. should inject the given LoggingContext into the HTTP headers of its outbound request:

func get(url: String, context: LoggingContext) {

var request = HTTPRequest(url: url)

InstrumentationSystem.instrument.inject(

context.baggage,

into: &request.headers,

using: HTTPHeadersInjector()

)

}On the receiving side, an HTTP server should use the following Instrument API to extract the HTTP headers of the given

HTTPRequest into:

func handler(request: HTTPRequest, context: LoggingContext) {

InstrumentationSystem.instrument.extract(

request.headers,

into: &context.baggage,

using: HTTPHeadersExtractor()

)

// ...

}In case your library makes use of the

NIOHTTP1.HTTPHeaderstype we already have anHTTPHeadersInjector&HTTPHeadersExtractoravailable as part of theNIOInstrumentationlibrary.

For your library/framework to be able to carry LoggingContext across asynchronous boundaries, it's crucial that you carry the context throughout your entire call chain in order to avoid dropping metadata.

When your library/framework can benefit from tracing, you should make use of it by integrating the Tracing library.

In order to work with the tracer configured by the end-user, it adds a property to InstrumentationSystem that gives you back a Tracer. You can then use that tracer to start Spans. In an HTTP client you e.g.

should start a Span when sending the outgoing HTTP request:

func get(url: String, context: LoggingContext) {

var request = HTTPRequest(url: url)

// inject the request headers into the baggage as explained above

// start a span for the outgoing request

let tracer = InstrumentationSystem.tracer

var span = tracer.startSpan(named: "HTTP GET", context: context, ofKind: .client)

// set attributes on the span

span.attributes.http.method = "GET"

// ...

self.execute(request).always { _ in

// set some more attributes & potentially record an error

// end the span

span.end()

}

}

⚠️ Make sure to ALWAYS end spans. Ensure that all paths taken by the code will result in ending the span. Make sure that error cases also set the error attribute and end the span.

In the above example we used the semantic

http.methodattribute that gets exposed via theTracingOpenTelemetrySupportlibrary.

Creating an instrument means adopting the Instrument protocol (or Tracer in case you develop a tracer).

Instrument is part of the Instrumentation library & Tracing contains the Tracer protocol.

Instrument has two requirements:

- A method to inject values inside a

LoggingContextinto a generic carrier (e.g. HTTP headers) - A method to extract values from a generic carrier (e.g. HTTP headers) and store them in a

LoggingContext

The two methods will be called by instrumented libraries/frameworks at asynchronous boundaries, giving you a chance to act on the provided information or to add additional information to be carried across these boundaries.

Check out the

Baggagedocumentation for more information on how to retrieve values from theLoggingContextand how to set values on it.

When creating a tracer you need to create two types:

- Your tracer conforming to

Tracer - A span class conforming to

Span

The

Spanconforms to the standard rules defined in OpenTelemetry, so if unsure about usage patterns, you can refer to this specification and examples referring to it.

import Tracing

private enum TraceIDKey: Baggage.Key {

typealias Value = String

}

extension Baggage {

var traceID: String? {

get {

return self[TraceIDKey.self]

}

set {

self[TraceIDKey.self] = newValue

}

}

}

var context = DefaultLoggingContext.topLevel(logger: ...)

context.baggage.traceID = "4bf92f3577b34da6a3ce929d0e0e4736"

print(context.baggage.traceID ?? "new trace id")Please make sure to run the ./scripts/sanity.sh script when contributing, it checks formatting and similar things.

You can ensure it always is run and passes before you push by installing a pre-push hook with git:

echo './scripts/sanity.sh' > .git/hooks/pre-pushWe use a specific version of nicklockwood/swiftformat.

Please take a look at our Dockerfile to see which version is currently being used and install it

on your machine before running the script.