This overview is to collect the thoughts and conversation points that we made during the Oxbridge Brainhack.

Example of a cortical parcellation from FreeSurfer. Accessed from: https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu.

This is a loosely structured summary of previous approaches to automatically label sulci and gyri of the human brain. This list is not exhaustive.

- FreeSurfer approach

- For example in Fischl et al. 2004 (Cerebral Cortex)

- Similar: Desikan et al. 2006

- Use Markov random fields that take into account the neighbouring labels

- register brain to a probabilistic atlas space based on cortical folding

- Use Baysian paramater estimating theory

- Multiple modalitis for data-driven parcellation

- Glasser et al., 2016 parcellation

- multilayer perceptron

- trained on semi-automated labels

- Brainvisa approach

- For example in Clouchoux et al. 2006

- anatomically constrained surface parametrization based on sulcal roots

- Mindboggle software

- Klein et al. 2005

- fragment 3D pieces of sulci using k-means algorithm

- Surface-fitting approaches

- For example Thompson et al. 1996

- register native to template space

- Yatershed-based approaches

- For example Lohmann at al. 1998 (Medical Image Analysis), Yang et al. 2008

- Sulci or sulcal segments form 'sulcal basins'

- assign labels based on mean locations

- Graph-based approach

- For example in Goualther et al. 1999

- A graph consisting of folds and junctions active ribbon

- semi-automated lablling by humans

- Pattern-recognition methods

- For example in Rivière et al 2002

- Graph matching approach

- multi-layer perceptron

The automatic segmentation of sulci can be described in the context of a computer vision problem. Therefore, we studied how segmentation is typically performed in pixel-based 2D images.

- Jargon: The term 'segmentation' is used for subcortical structures and 'parcellation' is used for the cerebral cortex

- Semantic segmentation: link a unit (for example a pixel) to a class label

- Instance segmentation: label multiple objects of the same category

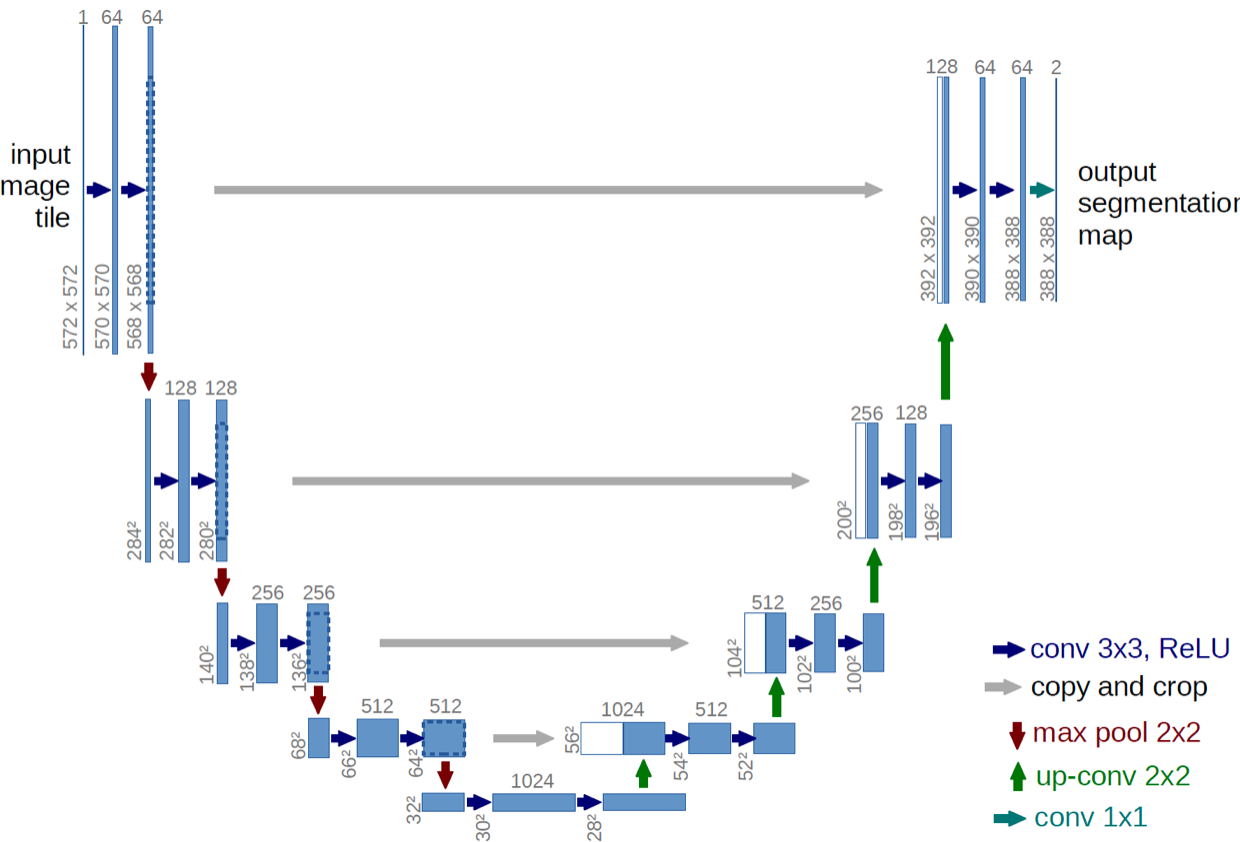

- One popular approach to automatize image segmentation: UNET

- UNET: Fully convolutional neural network network that implements convolution and max pooling for downsampling followed by upsampling

- First path: encoder, or contraction path, to capture the context in the image

- second path: decoder, or symmetric expanding path, to enable localization using transposed convolution

- Useful links:

Classic example for a segmentation problem: Classifying objects in real time during autonomous driving. Accessed via this website.

Original UNET architecture proposed by Ronneberger et al. 2015. Accessed via arXiv:1505.04597

We were interested in pursuing an approach using a convolutional neural network that works on the cortical surface (for example in Cucurull et al. 2018). Graph neural networks have gained popularity in computer science, and they can represent dependencies between nodes in a different way than pixel-based images.

The cortical brain surface is represented in form of a closed mesh that can be understood as undirected graph. The surface mesh consists of vertices (nodes) and edges, which form faces - triangles in the case of a brain surface (see Figure A below). In the case of the gifti file format (.surf.gii), the file stores two data arrays: A n x 3 array that stores the coordinates of each vertex in space and a m x 3 array that stores the indices of the vertices associated with each triangle (a,b,c in the example below). A metric file (.func.gii) contains the data associated with a vertex, for example a curvature map. These files store a n x 1 vector of values for each vertex.

Cortical mesh data is thus represented in non-Eucledian space, which means that we can't use a conventional convolution kernel as spatial operator. We can use the information from the triangles, however, to infer the indices of the neighbouring vertices (see Figure B below for an example with arbitrary indices). We can thus reshape the data so that for each vertex, we obtain a 1 x 7 vector of vertex indices that define a neighbourhood (see Figure C). A spatial convolution kernel that would cover the local neighbourhood of a vertex can be reshaped in the same way. A convolution can thus be performed by filling in the data from a metric file using the indices from the reshaped matrix and then multiplying each row with a kernel. The kernel thus slides downwards along all n rows. Due to the reshaping, we can then pass through further layers of a neural network. Example code for how such convolution can be performed can be found in one of our scripts

As an alternative approach we came across a relatively new software that has been specifically developed for segmentation of shapes: MeshCNN. The developers implemented convolution and pooling operations that work effectively on triangular meshes. During the learning process, important geometric features are learned, while redundant edges are collapsed. The software is open-source and it runs on the PyTorch backend. Adopting this software to work with brain surface meshes and cortical labels could be a promising new approach to automatic brain parcellation.