Koyaanisqatsi (Chaotic Life) is a research project that:

- demonstrates how deterministic behavior could emerge from blind random interactions of parallel processes;

- introduces a working dynamic error correction code for a universal computation model;

- presents an asynchronous parallel wait-free unsynchronized implementation of Conway's Game of Life, or a generic cellular automaton.

Here is a technical introduction:

A straightforward implementation of Life takes two arrays, initializes one to the initial state, then computes the new states of all cells in the other array, swaps the arrays, computes next generation of states in the first array, and so on. If all cell states in generation t are computed before any state in generation t+1, such implementation is synchronous. In other words, the internal time of Life is fully aligned with the external time of implementation (it's these two times that are synchronous). On the other hand, an asynchronous implementation allows for an arbitrary ordering of updates of two separate cells if, and only if, those updates are causally independent. A t+1-th update of a cell must happen after the t-th update of any of its neighbor cell, but if the two are far apart, the order of updates can be any.

There is some analogy here with breadth-first and depth-first search algorithms and the latter hints at how asynchronous updates can be implemented with some room for randomness ("real" or pseudo). Another analogy is with the idea of the "global clock": the synchronous approach implements it, the asynchronous one rejects it.

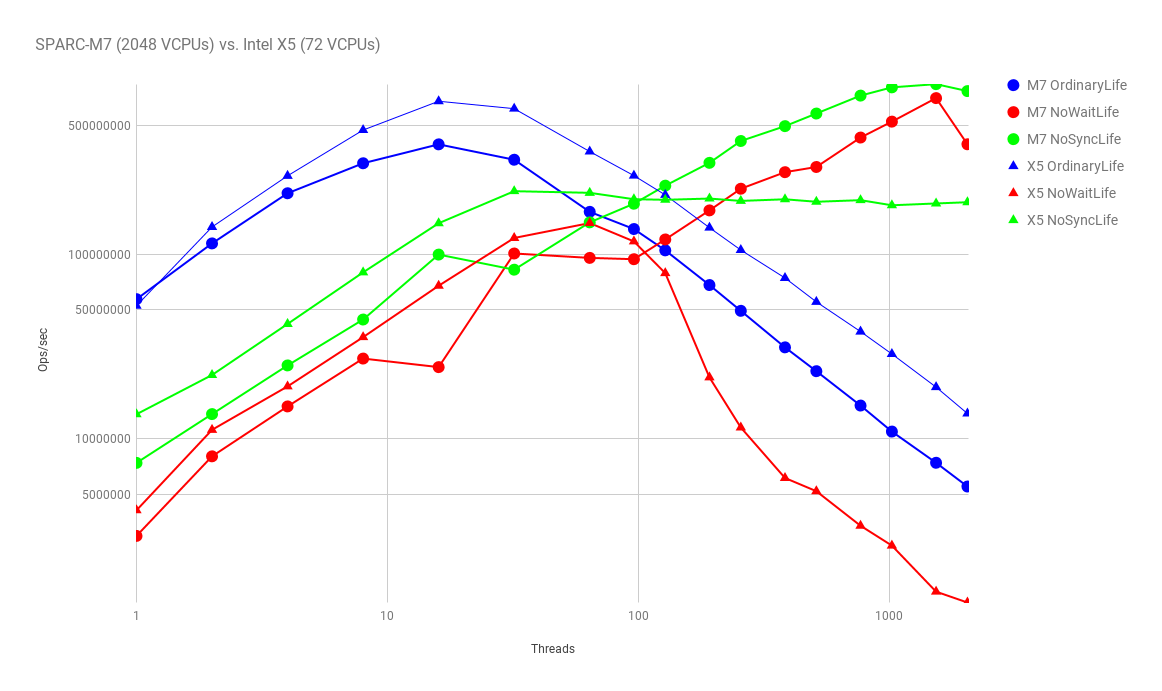

If we want to parallelize our algorithms we find that the synchronous one is "embarrassingly parallel" within one generation of updates but imposes a barrier for all parallel processes between two generations. It's a straightforward parallelization approach to a straightforward synchronous implementation (see OrdinaryLife.java). One thing is obvious: such implementation won't scale: just imagine a parallel computer the size of the Solar system and what it would take to reach a barrier for all its parallel computations - I'll call it the Solar system scalability test.

The asynchronous approach is trickier to parallelize but if you are familiar with Go you can imagine a network of go-routines and channels that will express all concurrency there is in Life. Will it pass the Solar system scalability test? Yes, but on one condition: if all your communicating serial processes are physical. We can easily create millions of go-routines on contemporary computers but we still have only so many cores and to execute our highly concurrent program we need to dynamically map our cores to our go-routines. In other words, we need a scheduler. And the problem is that it's very difficult for a scheduler to figure out which go-routine can make real progress, so, many of them will be allowed to run on a physical core only to find out that they still don't have enough input to compute their next state and have to loop back on the blocking select. The actual process, an OS thread, will never block but it will be running through lots of unnecessary switching to incomplete go-routines. Can we do better?

Yes, we can, if we implement our parallel asynchronous algorithm in a wait-free fashion (see NoWaitLife.java). All physical cores would always be busy updating cells as there is always enough work in Life (assuming the number of cores is much less than the size of the state). In some sense, such algorithm would implement a perfect scheduler which would always run only those cells that are ready for state update. In order to ensure correctness of our computation, we would naturally rely on the atomic Compare-And-Swap machine instruction readily available in all modern CPUs. No busy waits, no simulated locks nor semaphores - just atomic conditional updates of shared memory locations.

Our next problem is that now every cell update involves many atomic operations (working with blocks of cells is just a constant factor from scalability perspective). What that means is that all local caches are for nothing. A CPU has to go straight to shared memory and make sure it can perform its read-and-write cycle with no interference from other CPUs. Whichever way this is achieved - locks pushed down to memory blocks, cache coherence protocols, or whatnot - we know synchronization is in our way.

We always want to minimize synchronization between parallel processes but can we totally eliminate it? Not in Apple's way, of course:

DispatchLife.c

Due to the highly asynchronous nature of this implementation, the simulation's results may differ from the classic version for the same set of initial conditions. In particular, due to non-deterministic scheduling factors, the same set of initial conditions is likely to produce dramatically different results on subsequent simulations.

Can we eliminate synchronization, so that we wouldn't compromise correctness for more parallelism and better performance (not as dumb a trade-off as it may sound, but certainly not so much correctness)? Unsynchronized access to shared memory leads to data races - arguably the nastiest bugs in parallel programs. Can we compute reliably with data races? To the best of my knowledge the answer so far has been a firm no. If the answer is wrong, what could possibly undo the devastating effect of data races at scale? If two threads are simultaneously writing the same value to the same memory location, such data race is harmless. If one thread delays, however, the value may become obsolete and we'll need a way to detect and fix the error. To be able to do that we need to introduce redundancy into our computational process. If I were to describe my solution in one sentence, it would be "an error correcting code unfolding in time as computation".

So, here it is, an "asynchronous parallel wait-free unsynchronized" implementation of Life (see NoSyncLife.java). Of course, this is just a proof of concept. How reliable is it? It's probably too soon to try to answer this question. The presented implementation does not achieve the full potential of the code but, I believe, is good enough to start a conversation.

The project uses Java 8 and Maven (3.3.9), though it doesn't really have any dependencies. To run tests:

mvn test

To run indefinite tests, comment out the @Ignore annotation for testInfiniteNoSync() in LifeTest.java.

To run visualization, do one of the following:

mvn exec:java # NoSyncLife, Acorn pattern

mvn exec:java@counter # NoSyncLife, DecimalCounter pattern

mvn exec:java@acorn2 # NoWaitLife, Acorn pattern

mvn exec:java@counter2 # NoWaitLife, DecimalCounter pattern

mvn exec:java@acorn3 # OrdinaryLife, Acorn pattern

mvn exec:java@counter3 # OrdinaryLife, DecimalCounter patternTo create a jar file:

man packageTo run from jar:

java -jar target/ChaoticLife-1.0.0.jar [-T NOSYNC|NOWAIT|ORDINARY] [-w width] [-h height] [-t generations] [-p threads] [-novis] [<file>.rle]To build

mkdir -p target/classes

javac -sourcepath src/main/java -d target/classes src/main/java/org/sync/*.javaTo run visualization

java -cp target/classes org.sync.NoSyncLife -t 10000 -p 8

java -cp target/classes org.sync.NoSyncLife -t 10000 -p 8 -w 860 -h 1400 src/main/resources/DecimalCounter.rle

java -cp target/classes org.sync.NoWaitLife -t 10000 -p 8 -w 860 -h 1400 src/main/resources/DecimalCounter.rle

java -cp target/classes org.sync.OrdinaryLife -t 10000 -p 8 -w 860 -h 1400 src/main/resources/DecimalCounter.rleTo test

java -cp target/classes org.sync.OrdinaryLife -t 10000 -novis > golden

while (true) do java -cp target/classes org.sync.NoSyncLife -t 10000 -p 8 -novis > current && diff golden current; doneKoyaanisqatsi (Chaotic Life) is licensed under the Apache License, Version 2.0.

For additional information, see the LICENSE file.