Welcome. This project exists as a result of the conjecture that Ruby would be an excellent language for writing compilers. This belief is based on the observation that Ruby excels in handling complex data structures and relationships in a simple, flexible, easier-to-understand way. Further, the lack of long compile/link/load development cycles combined with excellent support for code unit and integration testing make Ruby a highly productive environment. In addition, Ruby is unique in having as a primary goal, the maximization of programmer joy!

Further, while Ruby is considered slow by many, this is less relevant in an application, like a compiler, where a lot of time is spent reading and writing files.

As a result, this toolkit is being developed for a number of reasons:

- To test the Ruby Compiler Conjecture.

- To build a platform that will permit others to develop compilers of their own.

- To demonstrate the principles of compiler design and construction without all of the obscuring ceremony and boilerplate of more conventional languages.

- To promote programming education and exploration, not the least of which, is the fact that in writing this, I will learn a great deal as well.

- As an enabler for my own compiler based projects.

So, just what are compilers? Well compilers are a member of a family of programs called translators. Translators are programs that accept an input and produce an output, equivalent to the input in a different representation. This can be shown as follows:

Let's take a look at the two parts of our diagram that are not the mystical cloud of magic compiler stuff. Namely, a brief note about the Input and Output. What forms can these take?

Input: The types of things we input into translators has not really changed a great deal over the years. It mostly consists of files containing text. Yes we have progressed from obsolete text encodings like Hollerith Cards, EBDIC and ASCII encoded text files, to now when most contemporary compilers use the versatile UTF-8 encoding. Nonetheless, it's still all blobs (or files) of text.

A few, rare cases use visual or graphical inputs to describe programs, but these are usually confined to tools for setting the appearance of applications with a graphical user interface GUI or proprietary systems with limited application like these or specialized applications.

As a result, to keep things simple, this project will focus on accepting text files as input.

Note: There are some interesting and dramatic exceptions. For example this Stack Exchange - Retrocomputing question about static binary translation which discusses compiling binary code in a game cartridge to native code on a conventional PC.

Output: In stark contrast, compiler output exhibits a large range, often available as options within the same program. These can include:

Raw Binary - A raw binary code image file suitable for "burning" into programmable memory. This used to be more common, but is sometimes still seen in compilers for very small embedded computer systems.

Text Binary - A text file with a text representation of binary file. This is done using formats like the Intel Hex or Motorola S-Record encodings. Again, this used to be more common. It has the advantage that it incorporates rudimentary error checking, absent from the raw binary format.

Executable - A binary executable format formatted according to operating system (Linux, Unix, Multics, etc) rules.

Object - A binary format suitable as input to a post-compiler tool called a linker. This is a very common output choice as it supports the creation of code libraries, mixed language programs and multiple compilation units.

Assembly - A text file that contains the assembly language equivalent of the input high level language. This is often an option to allow the generated code to be examined and verified to confirm correct operation of the compiler.

Language - A text file that contains the equivalent of the input high level language in another high level language. Examples of this include Cfront that accepted 'C++' code and generated 'C' code and Babel which accepts modern ECMAScript (aka JavaScript) and outputs an older, more widely supported, version of the same.

Interpretation - In this case, there is no output representation. Instead, after performing all the needed analysis and code generation steps, that code is run right away. This approach is used in Basic, Ruby, Python, and many other languages.

There are many classes of translators based on the nature of the input, the output, and the relationship between them. Let's take another look at the family of translators:

| Program Class | Input Type | Output Type | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembler | Low level | Machine code | 1 to 1 |

| Compiler | High level | Lower level | 1 to Many |

| Interpreter | High level | Performs actions | 1 to Many |

| Transpiler | High level | High level | Many to Many |

| Importer | Formatted Data | Data Structure | Many to 1 |

| Exporter | Data Structure | Formatted Data | 1 to Many |

Notes:

- Formatted Data is structured text that includes JSON, XML, HTML, YAML, etc.

- Data Structures are in memory-aggregations of structured data.

- Interpreters and importers are similar in that they both translate for immediate use. You could say an interpreter imports code and an importer interprets data.

- Exporters are really formatters not translators, but are shown here for completeness because they are the converse of importers. On that note one could also add the disassembler and decompiler, but that would be silly.

So, translators encompass a very wide variety of applications with many diverse requirements. They are also crucial in so many aspects of information processing that it should be no surprise that they are intensely studied and analyzed.

This diversity also shows why no one approach can ever handle all of these requirements. As a result, this project will stay pretty focused on compilers, however much of this material will be applicable to other sorts of translators.

We will try to keep as many options open as possible, even if this means we must compromise. In general, clarity and simplicity will be favored over complexity and raw performance.

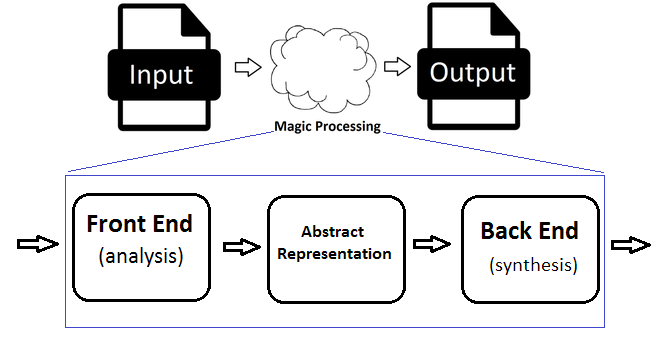

Now, our first diagram had entirely too much magic cloud going on for comfort. Let's see what happens when that TV forensics laboratory guy uses the dynamic, neochromatic image enhancer on that fuzzy cloud:

[Adapted from Modern Compiler Design, page 3, Figure 1.2]

A step up I suppose. Instead of a meaningless cloud, there are three boxes with rather broadly defined responsibilities.

WIP

Add this line to your translator's Gemfile:

gem 'rctp'And then execute:

$ bundle

Or install it yourself as:

$ gem install rctp

WIP

- Fork it ( https://github.com/PeterCamilleri/rctp/fork )

- Create your feature branch (

git checkout -b my-new-feature) - Commit your changes (

git commit -am 'Add some feature') - Push to the branch (

git push origin my-new-feature) - Create a new Pull Request

Go to the GitHub repository and raise an issue calling attention to some aspect that could use some TLC or a suggestion or an idea.

The gem is available as open source under the terms of the MIT License.

Everyone interacting in the rctp project’s codebases, issue trackers, chat rooms and mailing lists is expected to follow the code of conduct.

Lest anyone think that I am some sort of compiler guru genius, I am not. I learned about compilers the old fashioned way; by taking courses in school and by reading books. Both are very good, but the books cost a lot less money.

Here are some books that I found very useful. While there are references to these books through-out, some tiny snippets or ideas may be found as well. I want to gratefully acknowledge all of them.

Also, if you want to really step up your compiler skills, a serious read of these books could help a lot.

Modern Compiler Design (Dick Grune, Kees van Reeuwijk, Henri E. Bal Ceriel, J.H. Jacobs, Koen Langendoen, 2012) *1

WIP

Notes (1) - I here there is a 2016 edition now.