A one-file approach to having a libc for my WebAssembly modules. Technically there are 3 files, but two of them are virtually part of the main one due to being directly included in it, and also the allocator part is two extra files found in a separate project.

Typical libc implementations have specific priorities:

-

Total standard compliance.

-

Total mathematical accuracy.

-

High speed of execution that doesn’t harm compliance and accuracy.

-

Fallbacks for everything, in case a built-in function, OS function or CPU instruction isn’t available.

In a way there’s nothing wrong with these priorities because they’re what we collectively need. But this comes at a cost. Their code is usually big and complex, even trivial functions like memset() have complex implementations to handle every possibility as fast as possible. As a result, not only is their code several times bigger than strictly needed, it’s typically very hard to read and debug, it nests deeply and turns into a big bloated black box. Not only this, but because of the inconsiderate way they’re written they might force you to include advanced functionality that you don’t actually need. For instance simply calling WASI libc's sprintf() will include fprintf() which includes the extended WASI functionality for writing files from WebAssembly, which bothers me not only for technical reasons but also because such functionality is against my WAHE philosophy (I have lots of philosophies).

I for one don’t want all that junk, I have different, almost opposite priorities:

-

Simplicity at the expense of exhaustiveness and sometimes a bit of speed.

-

Only include the functionality I need.

-

Only have decent mathematical accuracy by default (which results in much higher speeds).

-

Minimal libc footprint in my binaries.

-

Calling one libc function doesn’t result in a dozen obscure functions being linked and called.

-

Code is very readable and debuggable.

In 2024 my experience with WebAssembly/WAHE is pushing me towards a desire to make everything clean. Instead of producing obscure executables that do and contain who knows what and make a mess in their memory space I feel a need to produce clean, minimal binaries whose binary contents are well understood by me and whose memory is clean, well-maintained (for instance free memory is blanked so that only current data would be seen), mappable and visualisable in real time and even directly readable at the byte level. I no longer want to do everything blindly like everybody else, vaguely assuming what’s going on without really knowing, without an awareness of what’s really in the binary and the memory, where it’s all located, how it’s laid out and what it looks like. When you see all of this you realise the absurdity of both your code and the libc implementation you rely on, and the next step is to do something about it.

One aspect of this philosophy relates to my more general philosophy of not optimising for anything specific. Optimising for something specific has a cost, the more you optimise extremely for something specific the more everything else gets sacrificed and suffers. This is very general and not specific to computer science, but it’s easy to see how it applies to code: optimising for one of speed, accuracy, standard compliance, fallback exhaustiveness, safety and simplicity at the expense of everything else will make everything else suffer and, except in the case of simplicity, lead to very complicated and unreadable code. And many programmers adhere to strict rules that say they must do this and can’t do that, so such rules are a form of extreme optimisation priority, everything must be sacrificed to respect those rules.

This philosophy is not about simplifying to an absurd degree, it’s about not really optimising for anything specific so we can keep things simple, it’s about rejecting any rule that gets in the way of a good result, yet still not optimising to get the best result. It’s not about making code that fits some rules, nor the best code, the simplest code, the fastest, the most accurate, the safest, it’s specifically about none of that. It’s about: if we can keep a function simple without making it bad, we’ll do that, if we can make it fast or mathematically fairly accurate without making it too complicated, we’ll do that, if we can comply with the standard without making it too bloated, we’ll do that, if not, we’ll stray from the standard in a way that we find acceptable, and quite importantly it’s also about not spending too much time on it.

The power of this philosophy is in getting things done. I’m just one guy and I want to do a lot of quality things by myself. A libc implementation is a great subject to put this philosophy to the test, because you can’t make the smallest, simplest, least bloated libc while also making the fastest, most mathematically accurate and standard compliant libc, but you can make a high quality libc that is fairly simple, small, unbloated, yet fast, reasonably accurate and sufficiently standard compliant for your own needs, and you can do it quickly (well, at least I can).

Creating your own libc sounds like a herculean undertaking, but not so with this philosophy. In just a few days I had all the functions I needed so I could compile and run an already existing module:

-

A lot of basic functions are defined as builtins, for instance

__builtin_sqrtforsqrt(), so those were dead simple to add. -

I adapted many of the most trivial functions like the functions defined in

ctype.handstring.hfrom WASI libc (which themselves come from other libraries) and cut out the bloat, such as removing the bulk ofmemcpy()that deals with optimally copying words as a fallback to the builtin implementation. -

I made approximations for mathematical functions like

exp(),log(),cos(),atan2(),asin()that are surprisingly simple, very fast compared to typical libc approximations that focus on maximal accuracy, yet with very decent accuracy to a few ULPs which makes them a very good compromise for most cases. -

What took me the longest, unsurprisingly, are my fully original implementations of

vsnprintf()andvsscanf(), which in accordance with my new philosophy are simple, only contain the features I currently need (no%anor%osupport for instance, I’ve never needed those) but still work just like the original for my use cases. -

I already have my own allocator called the Compact Info Table Allocator which I use in parallel to this.

It was quick, it’s dirty (although not as dirty as some libc implementations I’ve found), it does what I need correctly, as simply as possible and more accurately than truly needed. As I need more, I will add more, but because it will be mainly in new separate functions it won’t actually bloat up my existing modules as the functions it doesn’t need won’t be linked.

For a WebAssembly module that calls sin(), cos() and exp() and uses sscanf() and sprintf() to read and print decimal and hexadecimal integers, double values and match words, I get a 12.8 kB 32-bit WASM file:

-

1.1 kB for the module’s own code.

-

4.4 kB for CIT Alloc.

-

5.5 kB for

sscanf()andsprintf()together. -

0.5 kB for the mathematical functions.

-

0.4 kB for basic functions like

memset(),memcpy(),memmove(),strlen(),strchr(),strncpy(). -

The rest is various data.

The module’s map looks clear and clean, there’s no function included that isn’t truly needed, and unlike the same module built with WASI libc it’s not a 59 kB mess.

Look at it, it’s nice. You won’t often see a cos() implementation this straightforward.

Truly original and unique function implementations worth looking at:

-

vsnprintf()(the basis forsprintf()) which relies on a very niceget_power_of_10_exponent()to calculate digit counts. Supports%c,%s,%d%i%u%x%p,%g%f%ewith results that agree with an exact implementation up to about 17 digits, after that I get something different (I have no idea how default implementations are so accurate). -

vsscanf()(the basis forsscanf()). Supports%n,%c,%s%[]%[^],%d%i%u%x%p,%g%f%e. -

exp2()which works by directly calculating the IEEE-754 exponent of the result and calculating the rest by polynomial. -

log2()which works by taking the IEEE-754 exponent of the input which directly gives part of the result and applying a polynomial to the mantissa. -

cos_tr()(the basis forsin()andcos()) which very directly limits the range of the input and applies a simple polynomial. -

atan2()(which unusually serves as the basis foratan()instead of the other way around) which combinesyandxin an original way and applies a polynomial to them.

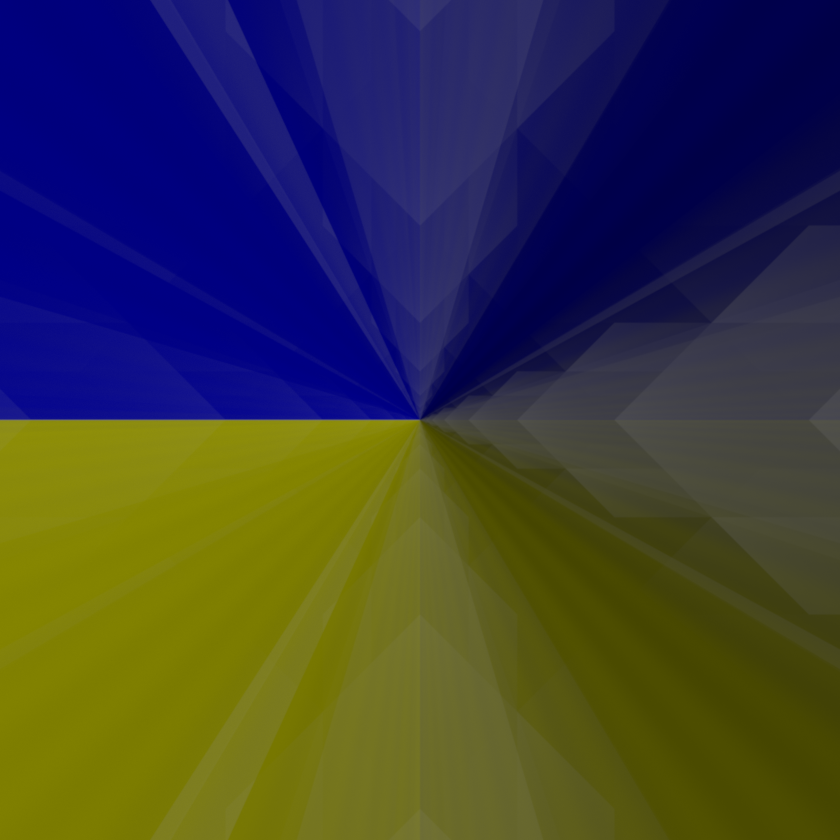

The difference between my atan2(y, x) and the standard implementation. Yellow is +4.5e-16, blue is -4.5e-16. The image appears dark because each pixel is a blend of higher and lower values (many zeroes).

-

asin()which "maps" the input (the polynomials approximate asin(2x-x2)) then does the upper end using a simple polynomial and the lower end using a rather short polynomial that is refined using two simple Newton-Raphson steps, meaning the accuracy of myasin()is somewhat impacted by the inaccuracy of mysin().

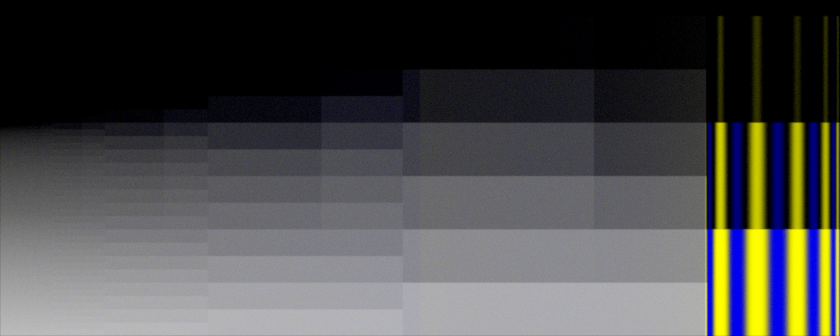

The difference between my asin(x) and the standard implementation. Horizontal is x = [0 , 1], vertical is y = [0 , 7e-16]. A pixel is set to yellow or blue (positive or negative difference) when the difference for that x is greater than y. Grey means an even blend of positive and negative differences around this x.

-

erf()which uses an actually fairly common 1 - polynomial-8 approach. -

qsort(), which is not my own work at all, but I looked hard for the best algorithm to suit this library and this one is nice for being small without being too inefficient. It’s a philosophical choice, it’s not as fast as multi-function recursive algorithms that are too complicated, and it’s not as absurdly slow as even simpler algorithms.

I use it along with CIT Alloc and my default WAHE-related headers in WebAssembly modules by writing this at the top of the module’s C file:

#define MINQND_LIBC_IMPLEMENTATION

#include "minqnd_libc.h"

#include "cita_wasm.h"

#define WAHE_INCLUDE_IMPL

#include <wahe_imports.h>

#include <wahe_utils.h>

#define CITA_EXCLUDE_STRING_H

#define CITA_WASM_IMPLEMENTATION_PART2

#include "cita_wasm.h"Note how there are no standard headers like stdlib.h, the litany of standard header includes from the original version of this module is gone, there’s only minqnd_libc.h. This is the minimal quick & dirty approach, we don’t need all these separate headers, we don’t need to conform to the standard for such details, this works.