Microservices are small, autonomous services that work together.

A microservice is a piece of code that could be rewritten in two weeks and feels small enough to be managed by a small team. The smaller the service, the more you maximize both the benefits and downsides of microservice architecture.

Microservices follow the single responsibility principle. All services are independent and focused on doing one specific functionality.

Microservice is a decoupled entity. It should be changed and deployed independently without affecting anything else. Services communicate via network calls to enforce separation and avoid tight coupling. Well-designed APIs are essential for decoupling, and they may be technology-agnostic.

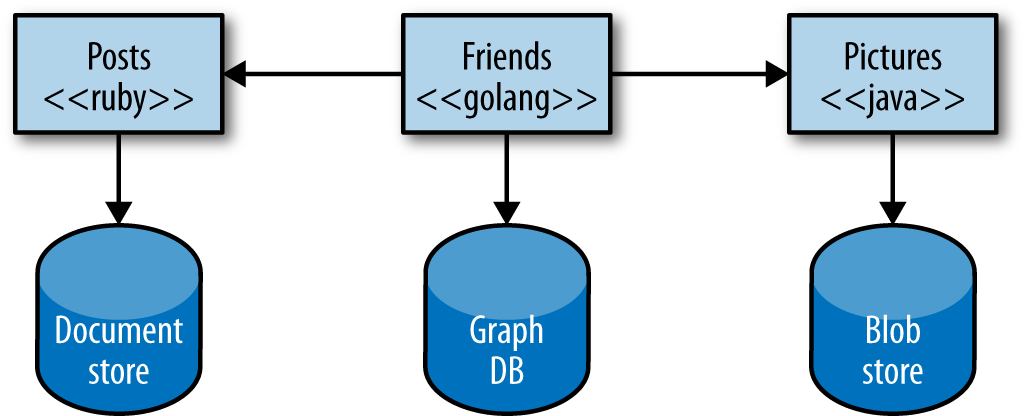

The microservices architecture provides the flexibility to choose the right technology for each job (i.e. service) rather than choosing a standard technology that fits all jobs in the monolithic architecture.

In a microservices system, If one service of a system fails, you can isolate the problem and the rest of the system can carry on working while degrading functionality. Unlike a monolithic system, If the service fails, everything stops working.

In microservices application, we can scale only services that need scaling. Unlike monolithic application, we have to scale everything together. This allows us to control our costs more effectively.

With microservices, we can make a change to a single service and deploy it independently. This allows us to get our code deployed faster. If a problem does occur, it can be isolated quickly to an individual service, making fast rollback easy to achieve. Unlike a monolithic application, small change requires the whole application to be deployed. This makes deployments end up happening infrequently.

Microservices help us minimize the number of people working on one codebase which improves productivity. As smaller teams working on smaller codebases is more productive.

With microservices, we allow for our functionality to be reused in different ways for different purposes. This can be especially important when we think about how our consumers use our software.

With our individual services being small in size, the cost to replace them with a better implementation, or even delete them altogether, is much easier to manage. While it's a costly job to rewrite or delete a big service in a monolithic system.

Service-oriented architecture (SOA) is a design approach where multiple services collaborate to provide some end set of capabilities. A service here typically means a completely separate operating system process. Communication between these services occurs via calls across a network rather than method calls within a process boundary.

It aims to promote the reusability of software and make it easier to maintain or rewrite software. The microservices is a specific approach to do SOA well.

A standard decompositional technique is breaking down a codebase into multiple libraries. Libraries give you a way to share functionality between teams and services.

But there are some drawbacks. You lose technology heterogeneity, the ease with scaling, and your ability to deploy changes in isolation.

Some languages provide their own modular decomposition techniques that go beyond simple libraries. They allow some lifecycle management of the modules, such that they can be deployed into a running process, allowing you to make changes without taking the whole process down.

But within a process boundary, it is also much easier to fall into the trap of making modules overly coupled to each other. So we still have the same shortcomings as we do with normal shared libraries.

Microservices are no silver bullet. They have all the associated complexities of distributed systems. Every system is different. A number of factors will play into whether or not microservices are right for you, and how aggressive you can be in adopting them.

Microservices give us a lot of choice and accordingly a lot of decisions to make. So, the role of the architect also has to change.

The term architect in our industry can lead to some terrible practices because it creates a view to inform the construction of the perfect system without considering the fundamentally unknowable future. A perfect system is a system designed to flex and adapt and evolve with user requirements. We are stuck with the word architect for now. So the best we can do is to redefine what it means in our context.

We have to accept that once the software gets into the hands of our customers we will have to react and adapt, rather than it being a never-changing artifact. Architects need to shift their thinking away from creating the perfect end product, and instead focus on helping create a framework in which the right systems can emerge, and continue to grow as we learn more.

Zones are our service boundaries, or perhaps coarse-grained groups of services. We need to worry much less about what happens inside the zone than what happens between the zones. That means we need to spend time thinking about how our services talk to each other, or ensuring that we can properly monitor the overall health of our system.

Defining a set of principles and practices helps us make decisions based on goals that we are trying to achieve.

Architects need to make sure the technology is aligned to organization high-level business goals.

Principles are rules you have made in order to align what you are doing to some larger goal, and will sometimes change. It's important to have a small number of principles to ensure that people can remember them and to not contradict each other.

Practices are how we ensure our principles are being carried out. They are a set of detailed practical technology-specific guidance for performing tasks.

One person’s principles are another’s practices. For a small group combining principles and practices might be OK. For larger organizations, you may want a different set of practices in different places, as long as they both map to a common set of principles.

![1. Microservices - Building Microservices [Book]](https://www.oreilly.com/api/v2/epubs/9781491950340/files/assets/bdms_0102.png)