The paper Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes combines variational inference with autoencoders, forming a family of generative models that learn the intractable posterior distribution of a continuous latent variable for each sample in the dataset. This repository provides an implementation of such an algorithm, along with a comprehensive explanation.

Prerequisites (explained in the introduction sections):

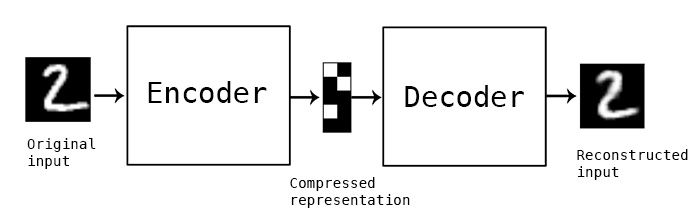

- Auto-encoders: This concept is crucial because VAEs are a specific type of auto-encoder. Understanding the architecture and purpose of auto-encoders, such as dimensionality reduction, and their relation to Principal Component Analysis (PCA), is fundamental.

- Generative Models: VAEs are generative models, which are able to generate new data samples that resemble the training data. Understanding what generative models are and how they work is important to understanding VAEs.

- Variational Inference: This is the statistical technique used in VAEs to perform the inference of the latent variables and to train the model. Understanding this technique is necessary to understand the training process and the capabilities of VAEs.

Dimensionality reduction is a technique used to reduce the computational complexity and enhance the interpretability of high-dimensional datasets (e.g. visualization).

The forthcoming sections will delve into two widely-used dimensionality reduction techniques: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Autoencoders. For an in-depth understanding of these algorithms, readers are encouraged to refer to their respective Wikipedia pages, which offer comprehensive explanations (relevant links will be provided in the text).

PCA is a linear transformation that captures the highest variance in data.

It transforms the input data by projecting it onto a set of orthogonal axes, derived from the data, called principal components.

When a linear transformation is adequate for dimensionality reduction, PCA often serves as the preferred method. However, for scenarios demanding more robust techniques, we may resort to sophisticated methods such as autoencoders.

StatQuest PCA video explanation can be found here.

Autoencoder are artificial neural networks that learn efficient data representations by encoding the input data into a lower-dimensional code and then decoding it to reconstruct the original input. Unlike PCA, autoencoders are not restricted to linear transformations.

In summary:

- The

encodergenerates a compressed representation of the input. - The

decoderreconstructs the original input from this compressed representation.

Image reference: Keras - Autoencoder

During the training phase, the objective is to optimize the reconstruction loss (for instance, by minimizing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) of the reconstructed input).

Potential applications include:

- Compressing the input data to a 2D or 3D form for simplified visualization.

- Image denoising, such as eliminating blur from an image.

Generative models are a class of unsupervised learning algorithms that create new data instances resembling your training data.

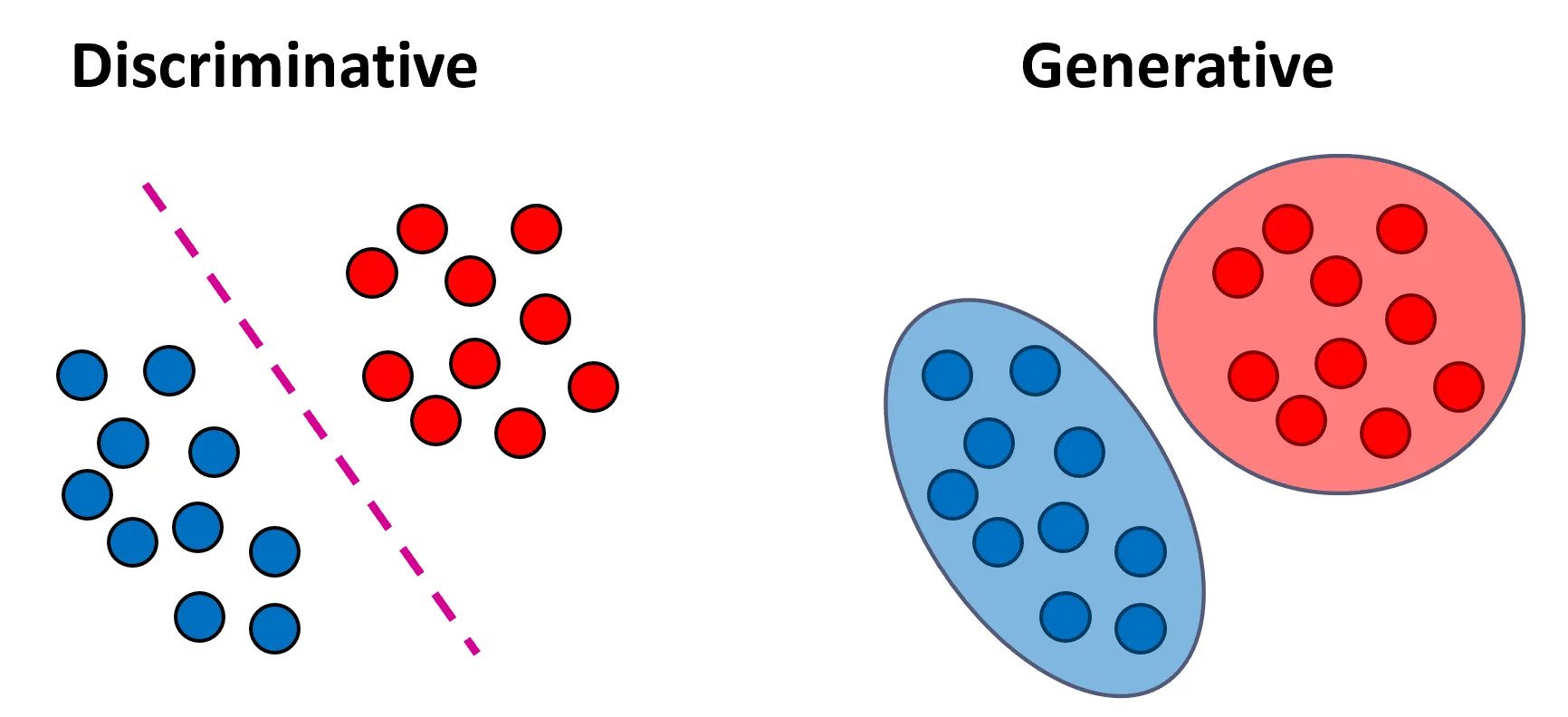

In contrast to discriminative probabilistic models, which model p(y|x) (the distribution of the output given the input),

generative models model p(x, y) (the joint distribution). This distinction enables generative models to synthesize novel data points.

Applications of generative models span various domains, including image synthesis, text generation, and more.

For classification tasks, discriminative models focus on learning the boundaries separating the classes, whereas generative models are concerned with understanding the distinct distributions of input data for each class. Refer to the image above.

Image reference: Medium - Generative vs. Discriminative Models

An example of a generative model is the Variational Autoencoder (VAE), while the vanilla autoencoder serves as an example of a discriminative model.

An autoencoder is a non-probabilistic, discriminative model, meaning it models y = f(x) and does not model the probability.

By applying variational inference and the autoencoder architecture, we can construct a generative model.

This generative model allows us to sample new data from the learned distribution once the model has been trained.

It also permits us to sample from the learned posterior conditioned on the input, which enables generating images similar to the input image.

Moreover, VAEs provide several additional benefits. They compel similar samples to cluster closely in the latent space and ensure that all samples are near the predefined VAE prior. This implicitly adds a regularization constraint on the encoder and also enables interpolation. Consequently, minor changes in the compressed representation lead to slight variations in the newly generated sample.

In order to explain the Bayesian variational inference method, we need to first refer to Bayesian approach and the intractability problem.

Bayesian inference is a method of statistical inference in which Bayes' theorem is used to update the probability for a hypothesis as more evidence or information becomes available.

In my perspective, the most intuitive way to comprehend Bayesian inference is by juxtaposing it with the frequentist approach.

When training a model (for instance, a classifier) on available data to perform inference,

one straightforward approach is to estimate the model parameters using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) -

Again, StatQuest video explanation for the maximum likelihood can be found here.

In cases where we possess prior knowledge about the parameter set

Keep in mind (this is crucial): If we establish the prior

In terms of Bayes' theorem, a latent variable signifies an unseen, fundamental feature that we strive to discern from the data at hand. Specifically in image processing, a latent variable could embody a non-visible attribute of an image, such as its inherent style or content. Ideally, we could recreate these images utilizing their corresponding latent representations.

Assume that we are working with images

We lack the marginal

Please note, this is an informal notation assuming that

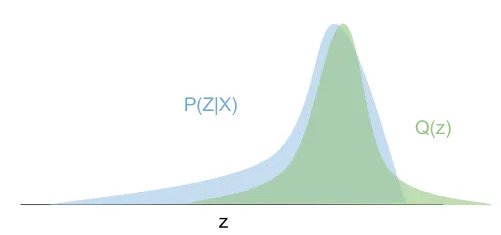

The concept behind variational inference is to recast the problem as an optimization of a surrogate distribution

We can use Kullback–Leibler divergence

to measure the similarity between the distributions

Although this isn't a distance since it isn't symmetric, it is always non-negative and equals 0 when the distributions match. Formally, we want to solve the optimization problem:

This cannot be directly applied since we don't have the posterior

$KL(q(z)||p(z|x)) = E_{z\sim q(z)}[log(\frac{q(z)}{p(z|x)})]$ -

$=E_{z\sim q(z)}[log(\frac{q(z)\cdot p(x)}{p(x,z)})]$ (conditional probability) $=E_{z\sim q(z)}[log(\frac{q(z)}{p(x,z)})]+E_{z\sim q(z)}[log(p(x))]$ $=E_{z\sim q(z)}[log(\frac{q(z)}{p(x,z)})]+log(p(x))$ $=-E_{z\sim q(z)}[log(\frac{p(x,z)}{q(z)})]+log(p(x))$

The Evidence Lower BOund (ELBO) i.e.

- We know:

$0 \leq p(x) \leq 1 \Rightarrow log(p(x)) \leq 0$ and $KL(q(z)||p(z|x)) \geq 0$ - Hence

$- E_{z\sim q(z)}[log(\frac{p(x,z)}{q(z)})] + log(p(x)) \geq 0$ - Finally:

$log(p(x)) \geq E_{z\sim q(z)}[log(\frac{p(x,z)}{q(z)})]$ .

But why is the ELBO important to use? We know that ELBO decreases ELBO with the optimal value being (if reachable)

when the ELBO reaches the evidence.

In the next section, we'll examine how we can combine variational inference with autoencoder architecture.

In this case we want to define the prior ELBO.

Gaussian distribution is a continuous probability distribution from exponential family that is often used because it is easy to work with. One of the main benefits of this distribution is that is a conjugate prior (posterior has the same probability distribution as the prior).

Let's assume that

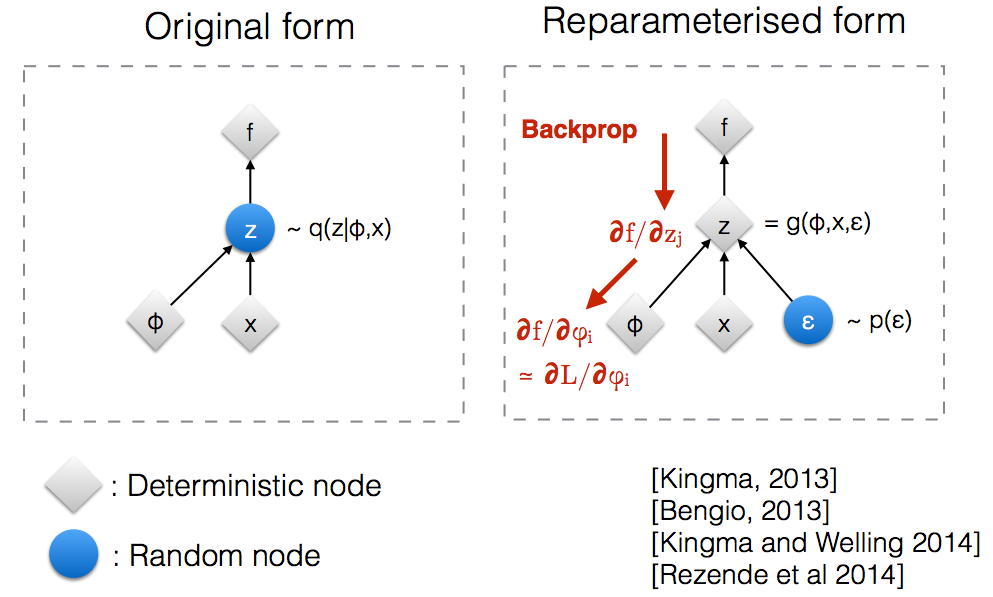

When maximizing the ELBO we have to estimate the expectation:

The problem here is that we can't back-propagate this way through the sampled values. Instead we can use the

reparametrization trick

where we sample from

Finally, we can derive the VAE loss function and the training algorithm using Gaussians under the following assumptions:

- Prior distribution

$p(z)$ is a standard Normal distribution:$p(z) \sim N(0, I)$ - Posterior distribution

$q(z)$ (or$q(z|x)$ ) is a Gaussian distribution parameterized by an encoder:$q(z|x) \sim N(f_e(x_i), g_e(x_i))$ , where$f_e(x_i)$ and$g_e(x_i)$ are the mean and variance respectively. -

$p(x|z) \sim N(f_d(z), c\cdot I)$ where$c$ is uncertainty hyperparameter.

Our loss for a single sample

$L_{f_e,g_e,f_d}(x_i) = \sum_j log(\frac{p(x_i,z_j)}{q(z_j)})$ $= \sum_j log(\frac{p(x_i|z_j)\cdot p(z_j)}{q(z_j)})$ $= \sum_j log(p(x_i|z_j)) + log(\frac{p(z_j)}{q(z_j)})$

Replacing

$log(p(x_i|z_j)) = log((\frac{1}{2\cdot \pi})^{\frac{d}{2}})\cdot |c\cdot I|^{-\frac{1}{2}}\cdot exp(-\frac{||x_i - f_d(z_j)||^{2}_{2}}{2\cdot c})$ - We can ignore everything except the part in the exponent since it is constant addition in the optimization problem.

$\sim -\frac{1}{2\cdot c}\cdot ||x_i - f_d(z_j)||^{2}_{2}$

For the term

$\sum_j log(\frac{p(z_j)}{q(z_j)})$ $=-\sum_j log(\frac{q(z_j)}{p(z_j)})$ $=-KL(q(z)||p(z))$ -

$=\sum_k \frac{1}{2} \cdot (1 + log(g_{e,k}(x_i)) - (g_{e,k}(x_i))^2 - {f_{e,k}(x_i)}^2)$ (reference)- Note: We sum over all independent random variables

$z_{j,k}$ over random vector$z_j$ .

- Note: We sum over all independent random variables

At the end we have:

$\sum_k \frac{1}{2} \cdot (1 + log((g_{e,k}(x_i))^2) - (g_{e,k}(x_i))^2 - {f_{e,k}(x_i)}^2) - \sum_j \frac{1}{2\cdot c}\cdot ||x_i - f_d(z_j)||^{2}_{2}$ - We want to maximize this term. We can also minimize the negative value.

- When using minibatch stochastic gradient descent, we can average the loss over all

$x_i$ data samples. - Also, when using minibatches, it is common to draw a single sample from the

$q(z)$ distribution for each element in the minibatch.

Finally, the algorithm is:

- Use the encoder to get the parameters of the posterior

$q(z)$ . Note that$q(z) \sim q(z|x)$ is actually conditioned on the input. - Draw one or more samples from

$q(z)$ distribution for each element in the minibatch (using the re-parameterization trick). - Run the decoder to reconstruct the input -

$p(x|z)$ . - Calculate the loss and backpropagate the gradients to update the parameters.

Remember, the ELBO is composed of two terms: the reconstruction term (which encourages the decoder to reconstruct the input well) and the regularization term (which encourages the posterior distribution to be close to the prior distribution). The balance between these two terms controls the trade-off between data fidelity and distribution matching, a common theme in variational inference.