Imagine you've been asked to design an embedded systems for an aircraft, car, or a medical device. These are embedded-systems where the operation of the device must be precise and correct. One very important consideration when designing a system is how long things take to execute.

Imagine you're responsible for designing part of an accelerator control system for a self-driving car. Your subsystem takes in readings from a LIDAR sensor, processes them, and sends the output to the accelerator controller. You may have quite a powerful microcontroller for your subsystem that can comfortably process the sensor data quickly and efficiently without too much trouble. However, if there is even a tiny chance that your system takes longer than it should, then you can have a big problem.

If your subsystem takes too long to process, it may result in a danger to life. Okay, but there are always risks in these things; what if any sort of delay is incredibly rare? Even if this is the case, it can present a severe issue. Imagine the self-driving car you are working on is deployed millions of times and runs for ten or more years. Suddenly the probabilities of even those very rare-events are starting to creep up, and any danger to life is unacceptable when we can design to avoid it.

When designing such embedded systems it is crucial that:

- Tasks need to execute with precise timing guarantees

- Embedded systems need to respond to external events with predictable timings

To make safe embedded systems, we need to ensure that our devices behave predictably concerning timing. To do that, we need to look into where unpredictable delays creep into typical systems and make the execution time non-deterministic.

A deterministic program is usually one where the program's outputted data is the same every single execution. However, with real-time systems, we take a stricter view on determinism and say that:

The systems outputted data and the timings of the outputs should be the same every execution

Our desktop computers are throughput orientated machines. They aim to get the most work done in a given time. If we have many tasks, the computer can execute them in an arbitrary order to maximise the most output. Typical machines are also abstracted to hide the system's timings to relieve the programmer's burden. Think about it: when you read or write to a variable in your program, or access a pointer, do you ever need to care how long it takes to fetch it from the memory subsystem? It's all completely invisible to you.

For real-time systems, such as the self-driving car we discussed earlier, timing is essential. This requirement means that different abstractions are required. After looking at the sources of non-determinism in typical computer systems, we will look at something called a Real-Time Operating System (RTOS). An RTOS puts the programmer in control of the timings of tasks.

Variations in execution time occur at all levels of the computer stack and in many different places. Some examples at various levels are:

- OS scheduler: when deciding which task to execute when

- In the Memory Hierarchy, for example, caching

- I/O Arbitration

- Internally within the CPU: branch prediction, speculative execution

Let's dig into a few of these in a bit more detail; unfortunately, we don't have time to explore everything that can introduce non-determinism (that would take a while).

Linux uses something called the Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS), which we won't go into the details of here. But the basic principles are that we have multiple processes, and the scheduler allocated processes to hardware CPUs trying to give all the processes an equal amount of resources.

The problem with this approach is that it treats all processes equally and fairly. Doing things this way is great for a desktop environment, where we are trying to maximise the throughput of all the processes we have, i.e. do the most work with the limited hardware we have. However, where this approach is a hindrance is when we have tasks that do have higher priority and that have latency requirements over other tasks.

When we have these sorts of requirements, as we often do with embedded systems, we need a Real-Time Operating System (RTOS) that considers tasks priority. We will go into the RTOS details in a little while.

A stark tradeoff exists in computer systems between data storage volume and access speed and cost. Managing the variation in access speeds can cause huge variations in execution time latency.

For instance, usually there is some high-speed SRAM memory that lives very close to the processor; however, typiucally, it's size is in the order of KBs or MBs. On the other hand, magnetic-disk based hard drives are a glacially slow storage medium, but their size is in the order of TBs.

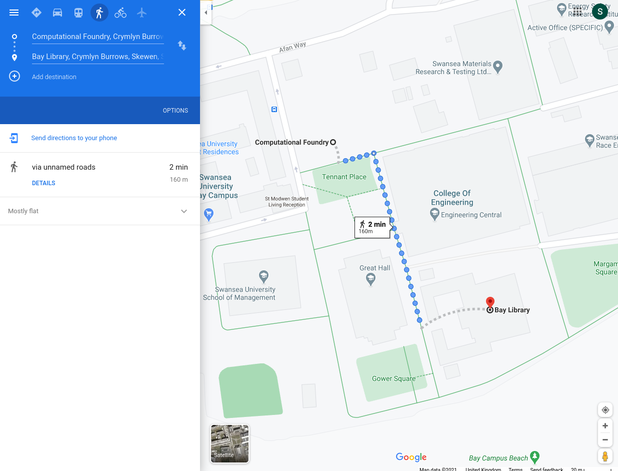

To put this tradeoff in perspective, let's consider an analogy. Let's say that accessing data from our fast SRAM close to our processor is equivalent to travelling from the Computational Foundry to the Bay Library to check out a book.

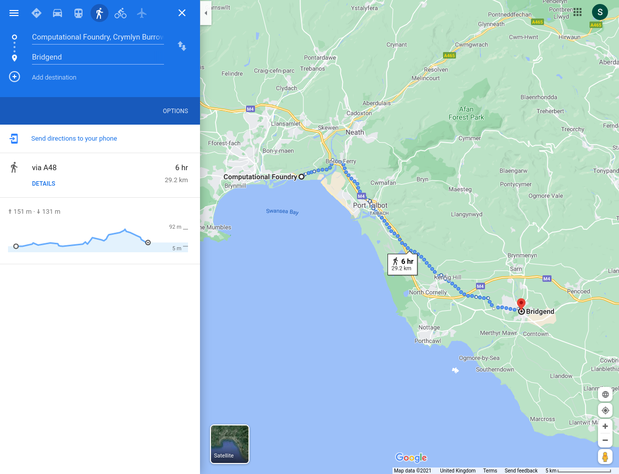

Okay, great, that didn't take too long. Now let's say that what we are looking for isn't in our fast SRAM, and instead, we have to go to System Memory (the RAM of our machine). If going to SRAM is the same as travelling to the Library, then going to System Memory is the same as travelling to Bridgend.

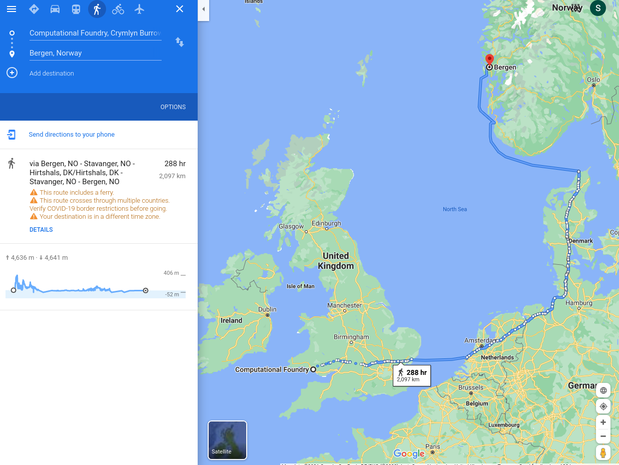

Now, say we can't find what we are looking for in system memory (system RAM), we need to start going to solid-state drive (SSD) storage to look for our item. Intel has recently released some blazingly fast SSDs based on a technology called 3D XPoint; let's imagine we're lucky one of these devices. Accessing this is the equivalent to going to Bergen, Norway.

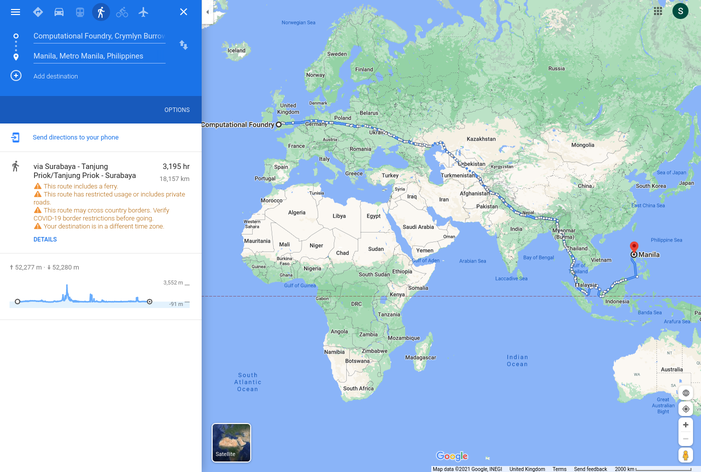

Okay, let's imagine that we are not so lucky, and we just have a standard run-of-the-mill SSD. Instead of travelling to Bergen, we're now travelling to Manilla.

Now, instead of an SSD, consider if we had a magnetic disk-based Hard Disk Drive. Then accessing our data would be the equivalent twice the distance to Mars.

This memory hierarchy is often shown as a pyramid that as you go up, you get increasing cost and performance, and as you go down, you get increased volume.

At the very bottom of the pyramid, I have included remote storage. Remote storage is becoming increasingly a concern for IoT style embedded systems that send their data to the cloud for storage.

Generally to manage this memory hierarchy we use something called caching, where we store recently used items in the faster access memory. Caching, introduces big variations in execution time, if the item is in the cache then we get a short execution time, if it's not in the cache, the execution time can be very long.

Let's consider the top level of the memory hierarchy, the fast SRAM memory close to the processor.

Say we are loading an item x from memory

First we check the fast access memory for x

If the item is not in the cache then we need to go to system memory (DDR)

We fetch the item from system memory (DDR) and load it into the cache

Then if a little later on we request x again, then it hits in the cache and accesses it much faster.

Thinking again about the scales discussed previously:

- A cache hit is like walking from the Computational Foundry to the Bay Campus library to check out a book

- A cache miss is like walking from the Computational Foundry to Bridgend to check out a book

No wonder cache's have a big impact on execution time variation.

It's not just memory and I/O that can introduce non-determinism in the execution time of a task. It's also possible to introduce it from within the CPU itself.

CPUs are generally organised a bit like a conveyor belt.

Instructions flow from left to right, and each unit does a little bit of work on each instruction as it passes through.

At any moment in time, each unit in the CPU will be working on a different instruction; this is something called pipeline parallelism.

The image above is a simple 5-stahge pipeline, where the stages are:

- Fetch: fetches the next instruction from the instruction memory

- Decode: decodes the instruction and fetches data from internal registers

- Execute: perform an operation with the ALU, such as add some numbers, or subtract

- Mem: send a read or write operations to memory

- Write back: writes data back into the registers of the CPU

One optimisation in many modern CPUs is something called speculative execution. Let's consider the following code:

if(x > 10) {

branch_1();

} else {

branch_2();

}If we fetch the instructions for the corresponding branch for if(x > 10), then we won't know what the following instructions are until the end of the Execute stage of the processor pipeline.

There are two things that you can do:

- stall the pipeline behind the

if( x > 10)until we know the outcome - guess and start fetching instructions

The guessing approach is called branch prediction, and modern CPUs are surprisingly good at it. . CPUs will use previous information on branches to make good guesses and keep the conveyor belt full and moving smoothly; the problem is when they guess incorrectly. After guessing incorrectly, the pipeline needs to be flushed, removing the incorrect instructions. Fixing this can take time and introduce delays.

So, that's another source of execution time variance. When we guess correctly, we go slightly faster than when we are incorrect.

Admittedly, this is a tiny performance boost compared to caches. The performance gains from caches are gigantic.

We are going to compare the execution of a benchmark function on two different platforms.

- An dual-core (800MHz) ARM processor running Linux

- Our ESP32 (240MHz) device

The benchmark we will use is a matrix-vector multiplication, a typical operation used in machine learning applications or signal processing.

Our benchmark code looks like this:

volatile float rvec [125];

volatile float rmat [125][125];

float res [125];

void matVecMul(){

for(int i=0; i<125; i++) {

res[i] = 0.0;

for(int j=0; j<125; j++) {

res[i] += rvec[j] * rmat[i][j];

}

}

}This function is a reasonably compute-intensive operation. We need to iterate over the entire matrix and multiple each element in the matrix row, with each element in the column of the vector, accumulating the result in the returned vector.

Don't worry if you don't follow the maths of this, it's just an example function we are using

As stated earlier, we will examine the execution time variance on two different embedded systems, an ARM-based system running Linux (PYNQ) and the TinyPico.

Each device connects to my home network. The PYNQ connects to the router via ethernet, as the ESP32 transfers data over WiFi.

Each device will execute the same benchmark. The execution time is measured, and each device sends its measurement via WebSockets to a central server. The server renders a dynamic histogram for each devices execution time.

The timer code only times the benchmark execution; none of the transfer time is captured or measured.

Running the benchmark on the PYNQ board produces the following real-time histogram of the execution time latencies:

The dashed lines show the different percentiles, i.e. the 75% line indicates that 75% of the latencies are to the left of the line, and 25% are to the right.

We can see there is quite a considerable variation in execution time here. There seems to be a peak above the 75% mark; this could due to other processes coming in and consuming CPU time.

It is also possible to see that the highest bin is quite full; this means that there are probably a couple of latencies that go off the chart (explored later).

When we start the experiment on the ESP32, the following histogram gets added below:

The results from the ESP32 are noticeably different from the PYNQ results. Here, we can see a variance in execution time of maybe 25us, whereas on the PYNQ, it varies wildly, >250us.

Notably, for the ESP32, the tail latency (99.99% point) is quite tight with the rest of the latencies, meaning that in the worst-case, the execution time is not much worse than the average case.

However, we do see that overall the ESP32 is considerably slower than the PYNQ. This slower speed makes sense. The PYNQs ARM CPU operates much faster; it runs at 800MHz instead of 240MHz. The ARM CPU is also a bigger, more complex processor with bigger caches.

Remember I said that the PYNQ latencies went off the chart. Let's zoom out to find out just how far they go.

Zooming out, we can see that occasionally the 99.99% point goes quite far out reaching over 465us!

Both devices connect to the network, and we can send network packets to them. When a network packet is received, the CPU will need to perform some tasks to process them.

Let's pretend that we are an attack trying to influence the functionality of an embedded system. We don't have access to the embedded system, but we have access to the network it is attached to, and we know the target devices IP address.

With this simple command, we can issue a flood of ping requests to the device, sending network packets as fast as we can:

ping -f 192.168.0.101As the embedded system processes these packets, it will have fewer CPU cycles to spare on processing the critical task, and the critical tasks execution time might increase.

Look at the histograms below when the ping -f command is issued and observe how the 99.99% latency point changes for the PYNQ device.

Interestingly, when the command is issued, we can see a considerable increase in the 99.99% latencies for the PYNQ board, but the ESP32 barely changes. On the ESP32, a small increase in 99.99% of just 1us, unlike the PYNQ, which increases by over 400us.

Why is the ESP32s latency not affected as much by the ping flood? The answer is because of the operating system on the ESP32. The ESP32 is running a Real-Time Operating System (RTOS). This RTOS schedules tasks differently from the Linux scheduler. On an RTOS, it's possible to assign tasks hard priorities, enabling them to take preference over other tasks. This prioritising allows our tasks execution to be barely affected by the increase in network traffic. However, the completely fair scheduler of Linux is trying to balance the load for all the system tasks, including processing the useless incoming network packets. Since the Linux scheduler is trying to do things fairly, this eats into the processing time allocated for our tasks, increasing its worst-case execution time.

Imagine a situation where we have constructed a self-driving car. In many of these complex systems, there are local networks that connect various embedded systems and modules. We don't need access to the system to effect it. We could place devices within the network that generate network traffic, seriously disrupting the victim system, causing it to miss deadlines, and potentially endangering lives.

Of course, if the attacker does have access to the PYNQ device, they can seriously disrupt our task's execution time. Look what happens when a user connects in via ssh:

[mini video lecture] This video is from last semester and refers to a lab 2 which is not applicable for this semester and can be ignored.

page 123 of [Making Embedded Systems] provides an excellent overview of interrupts

Interrupts force the CPU to respond rapidly to external events, like pressing a GPIO switch or internal events, such as an exception like a divide by zero.

Imagine you have to boil and egg which takes 7 minutes. Which is more efficient, occasionally checking your watch to see if the time has elapsed? Or is it better to set up an alarm to alert you that your 7 minutes had passed?

The same dilemma exists for embedded systems. Say we have the following setup:

How can we respond to the switch event as fast as possible? One possible way to detect a change on the switch is to write some code like this:

void setup() {

pinMode(5, INPUT);

}

bool pinState;

bool tmp;

void loop() {

tmp = digitalRead(5);

if(tmp != pinState) {

// the pin has changed state

pinState = tmp;

}

}In the above code, the microcontroller spins around the loop() body, periodically checking the state of our GPIO pin (5) to see if it has changed from the previous state. Regularly checking a pin like this is a technique called polling.

With the code above, we probably can pick up changes on GPIO 5 quite quickly. However, the issue comes when our Microprocessor has to do more than just spin in this loop. Consider the following:

void loop() {

tmp = digitalRead(5);

if(tmp != pinState) {

// the pin has changed state

pinState = tmp;

process();

}

}If our process() function call takes considerable time to compute, we might have an issue. This extra time will increase the latency that our microprocessor takes to respond to any change on GPIO 5. For some applications, this might be okay. Such as a multimedia entertainment system pause button, which can probably tolerate a few milliseconds of delay before processing. However, this can be safety-critical for other applications, for example, sensing a robotic arm's position in a factory automation setting.

Interrupts provide a hardware mechanism for responding to internal or external changes in the microcontroller. At a high level when an interrupt occurs the following happens:

- An interrupt request (IRQ) occurs

- The interrupt controller pauses the execution of the CPU

- The context of the CPU is saved

- A small function, specific for that interrupt is looked up and loaded onto the processor

- That small function is executed

- The context of the CPU is restored

- The CPU resumed from where it was interrupted

Essentially when an interrupt occurs, the control flow of the program is diverted temporarily from it's current path to execute a small specific function, known as an Interrupt Service Routine (ISR).

The hardware interrupt controller will have a fixed number of interrupts. We can think of these as channels connected to various peripherals and configured to generate interrupts under different conditions. If we look in the [ESP32 TRM] page 35 we can see a few more details about the Interrupt Matrix which is the interrupt controller for the ESP32. The TRM says that each of the two cores in the system has 32 interrupt sources, and there are a few extra for various exception handling, such as low-voltage detection.

In the interrupt controller we can also specify how the interrupt should be triggered.

| Trigger | Info |

|---|---|

| LOW | The interrupt is triggered while the signal is low |

| HIGH | The interrupt is trigged while the signal is high |

| CHANGE | The interrupt is triggered when the system is changing from low->high or from high->low |

| RISING | The interrupt is triggered when the system is changing from low->high |

| FALLING | The interrupt is triggered when the system is changing from high->low |

When an interrupt is triggered, the ISR location is looked up in a hardware Interrupt Vector Table. This table contains pointers to the ISR function's location that needs to be loaded onto the CPU. For more information on function pointers, checkout [Making Embedded Systems] page 66.

On the ESP32 an ISR is defined as follows:

void IRAM_ATTR myIsr() {

// ISR body

}It is a function that returns nothing void return type and takes no arguments. There is also one other unusual part IRAM_ATTR.

This is a compiler attribute used to signal where we want this function to be stored. On the ESP32, instructions are generally stored in the Flash memory of the ESP32 device. Flash is slow, but we have lots of it. However, in the case of interrupts, we want it to be as fast as possible. Using this attribute, we are saying that instead of the Flash memory, we want to store our ISR code in the fast internal RAM of our ESP32. Keeping our ISR here provides low latency access to the code, reducing the overall interrupt latency. However, this also raises an important consideration when designing ISRs...

ISRs should be as short as possible

We don't have a lot of internal RAM, and large ISRs will consume a lot of it. It's also a bad practice to have long interrupts. They hold up the processor, and when they go wrong, debugging them can be incredibly difficult. It is generally better to keep ISRs as short as you possibly can.

Interrupts can be nested inside one another, i.e. being interrupted by another interrupt during an ISR execution. Nested interrupts can sometimes be problematic and complicated. For instance, if we need to service an interrupt request in a fixed amount of time, there is a risk that another interrupt can jump in. This can make the execution time of the interrupt non-deterministic.

Generally, it is good practice to disable other interrupts while inside an ISR. Disabling interrupts is usually a simple task. Most microcontrollers possess a single hardware register that, when written, can disable interrupts in the system. On the ESP32 in Arduino, we can use the following to temporarily disable interrupts:

noInterrupts(); // I have been having difficulty with this

// This seems to work

portMUX_TYPE mux = portMUX_INITIALIZER_UNLOCKED;

portENTER_CRITICAL(&mux);And to re-enable them we can use:

interrupts(); // I have been having difficulty with this

// This seems to work to reenable interrupts

portMUX_TYPE mux = portMUX_INITIALIZER_UNLOCKED;

portEXIT_CRITICAL(&mux);Some interrupts are marked as Non-Maskable Interrupts (NMI); these are deemed so necessary that the hardware developers decided that they cannot be disabled. One notable example of this is the processor exceptions, such as low-voltage detection.

Finally, interrupts can have priority over other interrupts, where a nested interruption can only occur if the interrupt is a higher priority than what is being interrupted. On some microcontrollers, this is configurable; however, on the ESP32, it is static, with different peripherals and interrupts having a fixed priority. See page 38 of the [TRM], where Table 10 shows the different priorities for the various interrupts.

In the previous lecture and in the labs we have looked in depth at hardware timers. The ESP32 has a number of timer peripherals, each of which can generate an interrupt.

Each timer peripheral on the ESP32 looks like the following:

The timer hardware is essentially composed of two components. A 16-bit prescaler divides the input clock, and a 64-bit counter counts every clock cycle of the prescaled clock. The timer also accepts an alarm input, a 64-bit value that triggers an interrupt when the counter hits the alarm value. The counter is configured to either stop after an alarm has triggered or reloaded back to zero.

In the labs, you have been writing memory-mapped IO to configure the timer. However, there are some Arduino functions that we can use to configure the timer.

First, create a pointer to the hardware timer.

hw_timer_t *timer;Then we can use the following function to initialise the timer and get a reference to it.

timer = timerBegin(<timer number>, <timer prescale divider>, <count up or down>);

// for example

timer = timerBegin(1, 80, true); The timerBegin() function for initialising the timer takes three arguments:

1.The number of the timer 0-3

2. The amount the input clock is divided by. In the above example, we have 80, which means that we are dividing the 80MHz input clock down to a 1MHz clock making our counter increment every 1us.

3. Whether the counter counts up or down. In the above example, we have set this to true, meaning we count up.

The next thing that we need to do is attach an interrupt to the timer and specify and ISR.

timerAttachInterrupt(<pointer to our timer>, <pointer to our ISR> , <rising edge triggered>);

// example

void IRAM_ATTR timerISR() {

// ISR body

}

...

timerAttachInterrupt(timer, &timerISR, true);The timerAttachInterrupt() function takes three arguments:

- the pointer to the

hw_timer_tthat we defined previously and initialised withtimerBegin(). In the example above, this istimer. - A pointer to our ISR function. This function is executed when the timer interrupt occurs. In the example above, this is

timerISR, the address of the function is passed using the&operator. - A

boolvalue to state whether the interrupt is edge-triggered or not. In the example above, the interrupt will be edge-triggered.

The final two things that we need to do is tell the timer what it's alarm value is, i.e. the value that, when reached, triggers the interrupt; and enable the alarm on the timer. First, to write the alarm value into the timer, we can do:

timerAlarmWrite(<pointer to our timer>, <alarm value>, <generate alarm continuously>);

// example

timerAlarmWrite(timer, 1000000, true);The timerAlarm() function also takes three arguments to configure the point at which our timer module will generate an interrupt:

- A pointer to the

hw_timer_tthat we defined previously and initialised withtimerBegin(). In the example above, this istimer. - A 64-bit value that, when reached, will trigger the interrupt to occur. In the example, above this is

1000000, with the prescaler value set to80, this will generate an interrupt every second. - A boolean to say whether or not the alarm will continuously happen. In the example above, this is set to true, meaning that the interrupt will be triggered and then the counter will start all over again. Setting this to

falsecauses the interrupt only to get triggered once.

Finally, we need to enable the timer alarm to do that we use the function:

timerAlarmEnable(<pointer to our timer>);

// example

timerAlarmEnable(timer);The timerAlarmEnable() just takes one argument, the pointer to the hw_timer_t that we defined previously and initialised with timerBegin(). In the example above, this is timer.

And that's it. If configured correctly, our ISR will now be periodically executing every second.

Let's see this all put together with a complete example:

A Real-Time Operating System (RTOS) is typically a lightweight operating system for embedded devices that enable multiple tasks to share the same hardware resources while providing the developer control over tasks' timing.

The two critical components of an RTOS are the tasks and the scheduling ticks.

Tasks are a unit of functionality. You can think of them as similar to an ISR; however, they do not have some of the same restrictions. For instance, you can have quite large tasks as ISRs should be kept small. Some example tasks could be periodically encrypting a buffer full of data or occasionally blinking and LED.

Tasks in an RTOS have a few states that they can be in any given moment in time:

- They can be running: in which case they have been allocated a CPU and are executing.

- They can be ready: they have indicated to the RTOS that they are prepared to run, but are not currently running on a CPU.

- Or they can be blocked: they are waiting on a timer, or perhaps some external I/O and cannot run until that occurs.

The next main component of an RTOS is the tick, an ISR that executes periodically. A hardware timer on the MCU generates the interrupt that triggers the ISR. It is the responsibility of this ISR to schedule tasks onto processors.

Every "tick", the ISR will look at the tasks available and the currently running tasks and decide whether to swap what is presently running on the core.

Remember that tasks can either be running, ready, or blocked. The RTOS scheduler will look at all the running tasks and all the ready tasks and decide whether to swap a running task with a ready task. These scheduling decisions are often configurable, with different tradeoffs. However, the most common scheduling approach for an RTOS is Fixed-Priority Preemptive Scheduling.

Let's start with preemptive scheduling, which means that the operating system can swap what is executing on a given core with a different task. For instance, say task T1 is running on a CPU, then preemption means that before the T1 has completed, the RTOS can pause it, remove it from the core, and load T2 instead. T1 can then be resumed at a later point. Preemption is excellent because it allows us to have multiple tasks sharing the same hardware. However, we need to be careful. Swapping tasks, called a context switch, has overheads similar to the overheads of calling an ISR if we do it too frequently, then we will be wasting time and energy.

So RTOSs are usually preemptive, but they also have some notion of priority. Priority is what gives the developers control of the timing over the execution of the task. The example above shows T1 and T2 now assigned with priorities 5 and 0, respectively. With fixed-priority preemptive scheduling, we restrict the preemption such that only a higher priority task can preempt a lower priority task. This example would mean that T1 can preempt T0; however, T2 cannot preempt T1. Having a priority allows us to guarantee that certain critical tasks will complete in a tighter bounded amount of time. They are guaranteed to take control of the CPU, no matter what other tasks are executing.

Having priorities gives us a lot of control, but isn't there a danger? Won't the highest priority task take control over the CPU and starve all other tasks from executing?

Preventing the starvation of tasks is where the notion of blocking comes into play. Blocking is where a task must voluntarily release control of the CPU to allow other tasks to execute. It is also something that the embedded system developer must explicitly think about when designing the system. There are two primary ways for a task in an RTOS to block:

Tasks can block by either going to sleep or waiting for an event or message. When a task goes to sleep, it places it into a blocked state for a finite number of RTOS ticks, allowing another task to execute. When the amount of ticks elapses, the RTOS, during the scheduling ISR, will wake up the task and change its state to ready. The other way a task can block is waiting for a message from another task; or an event, like I/O being made available.

Let's consider an example:

Say we have three tasks, T1, T2, and T3. Each of these tasks has priorities 5, 3, and 0, respectively.

-

T1 enters an infinite loop

while(true)and then calls a function to collect some data withgetData(). It then goes to sleep for 1000 ms (1s), placing it in a blocked state. -

T2 also enters an infinite loop where it calls a function to process the gathered data

processData(). It then goes to sleep for 3000 ms (3s). -

Finally, T3 also enters an infinite loop where it calls a function that flashes an LED; it never sleeps and never enters a blocking state.

Let's say that initially, T3 is executing, and it is blinking the LED for 1 second.

After 1s, T1 wakes up and gets scheduled on the cores, preempting T3, as it has a higher priority than T3. Once it has finished executing, it goes to sleep, and T3 resumes running from where it left off.

After another 1s the same thing happens again: T1 wakes up, preempting T3.

Finally, after 3s, T2 is ready to wake up. However, at this point, T1 wakes up also. Since T1 has a higher priority than T2, it takes control of the processor first. Once it finishes, T2 can then execute before finally allowing T3 to run.

An RTOS is a powerful and useful abstraction to use when designing embedded systems. They abstract a lot of the task management, are simpler and safer to use than ISRs, and only require a single timer to schedule multiple tasks with real-time constraints.

An RTOS is a powerful and valuable abstraction to use when designing embedded systems. They abstract away a lot of the task management, are simpler and safer to use than ISRs, and only require a single timer to schedule multiple tasks with real-time constraints. However, care still must be taken. It is the programmer's responsibility to correctly implement tasks appropriately and ensure that tasks block preventing other tasks from being starved.