The material in this repo is part of a seminar at Princeton University. Feel free to use it as you like.

Often, we describe images or catalog features by what we call a "measurement", which is a pre-defined function of the data, but the term is somewhat overloaded. Let's have a closer look.

In statistics, a predefined function evaluated for a sample is called a sample statistic. That statistic may be regarded as an estimator of a parameter of the underlying model or parameterization of the population from which samples are drawn. It can also be used for a hypothesis test about the sample.

Example: If we have a noisy image of a star

Data Science happens at the level of sample statistics, or in our jargon: at the catalog level (I'll break that rule below..), i.e. once the measurement has been made. It doesn't deal with defining the statistic, instead it seeks to characterize the underlying populations based on multiple statistics of typically large numbers of samples.

The analysis approaches fall into two large groups:

-

Supervised techniques are based on data, for which independent and dependent variables/features are known, i.e. there are samples

$(x_i,y_i)$ of the mapping$X \rightarrow Y$ . The task is then to learn the mapping. Again, two types arise:-

$Y$ is the space of continuous variables, typically$\mathbb{R}$ or$\mathbb{R}^d$ . This is colloquially known as "fitting a model to data" and officially as regression. -

$Y=\lbrace L_1,\dots,L_K \rbrace$ is finite set of class labels, and each sample$x_i\sim X$ is assumed to belong to one class. The task is then called, well, classification.

-

-

Unsupervised techniques are those for which only samples

$x_i\sim X$ are available. The goal is then to describe their distribution in$X$ (density estimation) or their labeling (clustering). One can therefore think of these tasks as equivalent to the supervised ones, but with the additional complication that the "output" of the mapping is never observed. For instance, density estimation wants to find the mapping$X\rightarrow Y=p(X)$ , where$p(X)$ refers to the probability density distribution of the$x_i$ .

Another set of techniques is often required to aid the ones above, namely those for dimensionality reduction. It's often easier to perform analyses in low-dimensional spaces, which is why high-dimensional spaces are said to be cursed. Think of looking at data by eye, where we can work in 2D or 3D, but if we want to inspect even more features we need to map them onto graphical characteristics, like shape or colors of markers. The key of dimensionality reduction is to determine which aspects of the data are not important. If there are relations between features in the data, one can transform the feature space into one with a lower dimension. The crux is to know or guess the type of relations to determine which transformation is best.

Examples:

- All scaling relations in astronomy!

- Slightly more complicated: The HR diagram clearly shows structure, but the relations aren't linear or power-law-like everywhere.

Here's the fun part… scikit-learn is a single python package that implements all of the above. You may find that specific methods are missing, but overall it really covers the bases with a common interface. Data can be handled as numpy arrays, scipy sparse matrices, and pandas DataFrames. That makes scikit-learn powerful for smaller analyses and fast exploration. Moreover it's very well documented with a neat tutorial.

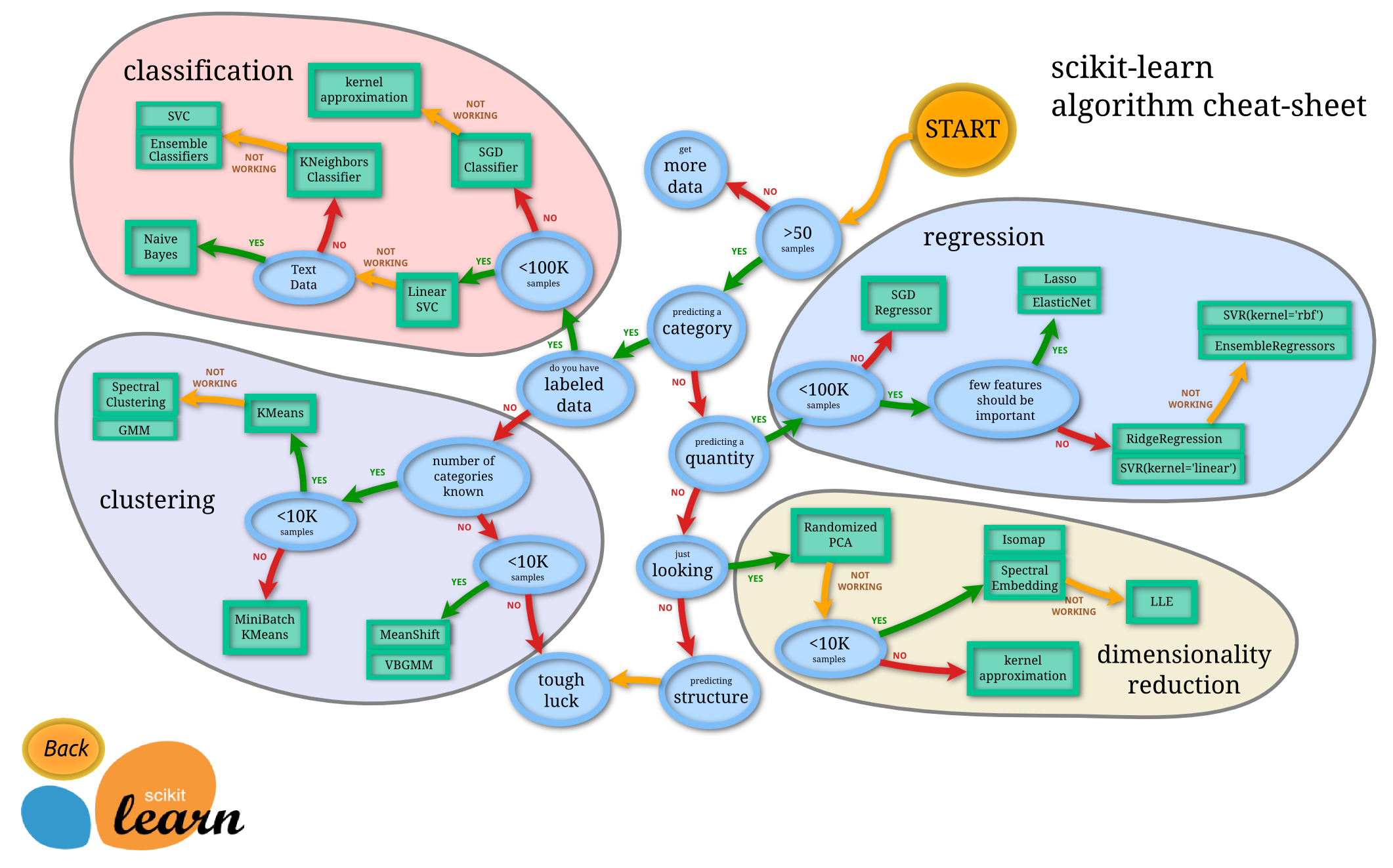

If you feel a little overwhelmed by the options, their algorithm cheat sheet (more a decision tree, really) is quite useful:

Note the split at the 3rd node "predicting a category". In this tree it happens before the question whether the data are labeled (the supervised—unsupervised divide). That is in line with treating unsupervised methods similar to those that are supervised, but with response variables ("labels") that are never observed. Also, this chart doesn't include density estimation, the unsupervised cousin of regression.