Tips and tricks for making components shareable across different projects (framework agnostic).

Components are now the most popular method of developing frontend applications. The popular frameworks and browsers themselves support splitting applications to individual components.

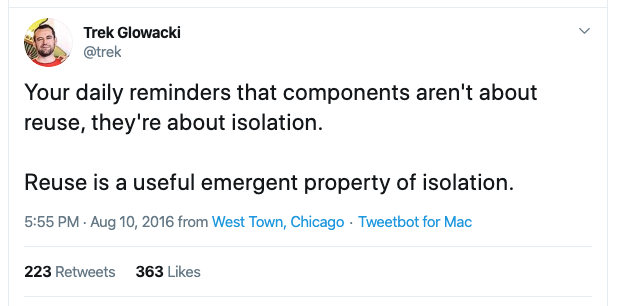

Components let you split your UI into independent, reusable pieces, and think about each piece in isolation.

Why me?

This series summarizes what I have learned in the last months working as head of Developer Experience at Bit. Bit is a components collaboration tool that helps developers build components in different applications and repositories and share them.

During this period, I have seen components developed by many different teams and across different frameworks. The good parts and the bad parts have led me to define some guidelines that can help people build more independent, isolated, and hence reusable components.

- Reusable Components Styleguide

✅ Do: Put all the component related files in a single directory, including component's code, stylings, tests, documentation, storybook stories, and testing snapshots. If your components is using sub-components, i.e., components that you can only use within the context of the parent component (List and ListItem or a component and its styled component), it make sense to include them in the same directory. Component consumer is getting all the components packaged together.

├── Button.spec.tsx

├── Button.stories.tsx

├── Button.style.tsx

├── Button.tsx

└── __snapshots__

└── Button.spec.tsx.snap

1 directory, 5 files❌ Avoid: Placing files according to their type in different directories.

├── components

│ ├── Button.style.tsx

│ └── Button.tsx

├── stories

│ └── Button.stories.tsx

└── tests

├── Button.spec.tsx

└── __snapshots__

└── Button.spec.tsx.snap

4 directories, 5 files❔Why?

The component produces creates a directory structure that is easily consumable by placing all the related files together. Having all files located in a single directory makes it easier for component consumers to reason about the items that are interconnected. File references are becoming shorter and easier to find the referenced item. Shorter file references make it easy to move the component to different directories. A typical reference pattern is:

style <- code <- story <- test

The component code is importing the component's style (CSS or JS in CSS style). A story (supporting CSF format) is importing the code to build the story. And the test is importing and instancing a story to validate functionality. (It is also totally ok for the test is directly importing the code).

✅ Do: Reference other components using aliases.

import { } from '@utils'❌ Avoid: using relative pathname to other components.

import { } from '../../../src/utils';❔Why?

Having a path like the above makes it hard to move the component files around in our project, as we need to keep the reference valid. Using backward relative paths couples the component to the specific file structure of the project and forces the consuming project to use a similar structure.

Webpack, Rollup, and Typescript provide methods for using fixed references instead of relative ones. Typescript uses the paths mapping to create a mapping to reference components. Rollup uses the @rollup/plugin-alias for creating similar aliases, and Webpack is using the setting of resolve.alias for the same purpose.

Component's APIs are the data attributes it receives and the callbacks it exposes. The general rule is to try and minimize the APIs surface to the necessary minimum. For component producers, this means to prepare the APIs so they are logical and consistent. Component consumers get APIs that are simple to use and reduces the learning curve when using the component.

✅ Do: Use discrete values such as Enums or string literals for requiring specific options.

type LocationProps = {

position: 'TopLeft' | 'TopRight' | 'BottomLeft' | 'BottomRight'

}❌ Avoid: using multiple booleans

type LocationProps = {

isLeft: boolean,

isTop: boolean,

}❔Why? Interdependencies between parameters make it harder for the consumer to use it. Creating more simplistic params paves a smoother way for developers to consume the components.

✅ Do: Set reasonable defaults for most params

type LocationProps = {

position: 'TopLeft' | 'TopRight' | 'BottomLeft' | 'BottomRight'

}

defaultProps = {

position: 'TopLeft'

}❌ Avoid: Making parameters required and expect user to fill in values for all of them.

❔Why?

Setting parameters makes it easy for the consumer to start using the component, rather than find fair values for all parameters. Once incorporating the component, tweaking it to the exact need is more tranquil.

✅ Do: get globals in the component's APIs instead of accessing a global param

export const Card = ({ title, paragraph, someGlobal }: CardProps) =>

<aside>

<h2>{ title }</h2>

<p>

{ paragraph + someGlobal.value }

</p>

</aside>❌ Avoid: Assuming a value

Components may rely on globals, such as window.someGlobal, assuming that the global variable already exists.

❔Why?

Relying on parameters gives the consuming application greater flexibility in using the components and does not require it to adhere to the same structure that exists in the producing application.

✅ Do: Use reasonable defaults when accessing globals that may not exist

if (typeof window.someGlobal === 'function') {

window.someGlobal()

} else {

// do something else or set the global variable and use it

}❌ Avoid: accessing global with no safe fallback

window.someGlobal()❔Why?

Fallbacks let the consuming application a way to build the application in a manner that is less coupled to the way the provider application. It also does not assumes that the global was set at the time it is consumed.

Our code relies on third-party libraries for providing specific functionalities, such as scrolling, charting, animations, and more. Third-party libraries are important but take care when adding them.

✅ Do: Define packages that are likely to exist in the consuming app as peerDependency with relaxed versioning.

"peerDependencies": { "my-lib": ">=1.0.0" }

❌ Avoid: specifying very strict version as dependency

"dependencies": { "my-lib": "1.0.0" }

❔Why?

To understand the problem, let's understand how package managers resolve dependencies. Assume we have two libraries with the following package.json files:

{

"name": "library-a",

"version": "1.0.0",

"dependencies": {

"library-b": "^1.0.0",

"library-c": "^1.0.0"

}

}

{

"name": "library-b",

"version": "1.0.0",

"dependencies": {

"library-c": "^2.0.0"

}

}The resulting node_modules tree will look as follow:

- library-a/

- node_modules/

- library-c/

- package.json <-- library-c@1.0.0

- library-b/

- package.json

- node_modules/

- library-c/

- package.json <-- library-c@2.0.0You can see that library-c is installed twice with two separate versions. In some cases, such as with React or Angular frameworks, this can even cause errors. However, if the configuration is kept as follow:

{

"name": "library-a",

"version": "1.0.0",

"dependencies": {

"library-b": "^1.0.0",

},

"peerDependencies": {

"library-c": ">=1.0.0"

},

}

{

"name": "library-b",

"version": "1.0.0",

"dependencies": {

"library-c": "^2.0.0"

}

}library-c is only installed once:

- library-a/

- node_modules/

- library-c/

- package.json <-- library-c2@.0.0

- library-b/

- package.jsonAlso, make sure the peer dependency has very loose versioning. Why? When installing packages, both NPM and Yarn flatten the dependency tree as much as possible. So let's say we have packages A and B. They both need package C but with different versions — say 1.1.0 and 1.2.0. NPM and Yarn will obey the requirement and install both versions of C under A and B. However, if A and B require C in version ">1.0.0", C is only installed once with the latest version.

✅ Do: Revise package.json dependencies often to make sure they are all in use. Prefer language features over packages (e.g. lodash vs. built it functions).

❌ Avoid: Using functionality duplicated across multiple packages.

❔Why?

When reusing code, you also need to reuse the packages that use it. Relying on multiple packages makes it hard to move components between applications, but also increase bundle size for all the component consumers.

By design, CSS is global and cascading without any module system or encapsulation.

✅ Do: Use a CSS mechanism that scope the style to the component. In React the popular css-in-js frameworks such as Emotion, Styled Components and JSS are famous. Vue is supporting scoped styled out of the box. Angular also has scoped styles built in with the viewEncapsulation property. CSS is scoped in web components via the Shadow DOM.

❌ Avoid: Rely on application level styles in components.

❔Why?

When reusing components across different apps the application level styles are likely to change. Relying on global styles can break styling. Encapsulating all style inside the component ensures it looks the same even when transported between applications.

✅ Do: Use themes to control the properties that you want to expose in your components.

class ThemeProvider extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<ThemeContext.Provider value={this.props.theme}>

{this.props.children}

</ThemeContext.Provider>

);

}

}

const theme = {

colors: {

primary: "purple",

secondary: "blue",

background: "light-grey",

}

};❌ Avoid: Let component consumers override any style property from outside.

❔Why?

Component producer need to control the functionality and the behavior of the component. Reducing the levels of freedom for the components consumers can provide a better predictability to the component's behavior, including its visual appearance.

✅ Do: Use CSS variables for enabling theming. See here for more details. CSS variables that can be used for theming should be documented as part of the component's APIs.

:root {

--main-bg-color: fuchsia;

}

.button {

background: fuchsia;

background: var(--main-bg-color, fuchsia);

}❌ Avoid: Other theming techniques are also valid.

❔Why?

CSS variables are framework independent and are supported by the browser. Also, CSS variables provide great flexibility as they can be scoped to different components.

Components may use state managers such as Redux, MobX, React Context, or VueX. State managers tend to be contextual and global. When reusing components between applications the consuming applications must have the same global context as the original one.

✅ Do: Separate presentational and container components. In most cases the data is specific to the consuming application. Component producers should provide presentational component only with APIs to get the data from a wrapping component that is managing data and state.

//container component

import React, { useState } from "react";

import { Users } from '@src/presentation/users'

export const UsersContainer = () => {

const [users] = useState([

{ id: "8NaU7k", name: "John" },

{ id: "Wxxfs1", name: "Jane" }

]);

return (

<Users data={users}>

);

};

//presentational component

export const Users = (props) => {

return (

<div className="user-list">

<ul>

{props.data.map(user => (

<li key={user.id}>

<p>{user.name}</p>

</li>

))}

</ul>

</div>

);

};❌ Avoid: sharing components that rely on a specific structure of data and enforce the consuming application to provide the data in a very specific format.

//single component that manages both data and presentation

import React, { useState } from "react";

export const Users = () => {

const [users] = useState([

{ id: "8NaU7k", name: "John" },

{ id: "Wxxfs1", name: "Jane" }

]);

return (

<div className="user-list">

<ul>

{users.map(user => (

<li key={user.id}>

<p>{user.name}</p>

</li>

))}

</ul>

</div>

);

};✅ Do: Package your components in multiple formats that are supported by the various platforms: CommonJS (or cjs, or sometimes called es5 modules) for nodejs consumption ES Modules (sometimes also referenced as es6 modules), to be consumed by bundlers and enable tree shaking. UMD, for using directly in script tags in the browsers Use the package.json fields to direct to the different formats as per this convention:

# Package.json

"main": "component.cjs.js"

"module": "component.es.js"

"browser": "component.umd.js"❌ Avoid: Assuming the component is consumed in only a specific way:

❔Why?

The JS world has a unique trait of a single interpreted language that is running on multiple platforms. Nodejs in various versions and various browsers create a plethora of runtime environments.

Despite a continuous shift towards standard module handling, there are still a variety of methods to handle bundled code.

During this struggling period and until we get one standard to rule them all, we should be good citizens of the JS-universe by feeding each packaging beast with its favorite flavor.

For example, Webpack supports the different fields, according to the target it is building for.

//webpack.config.js

//When the target property is set to webworker, web, or left unspecified:

module.exports = {

//...

resolve: {

mainFields: ['browser', 'module', 'main']

}

};

//For any other target (including node):

module.exports = {

//...

resolve: {

mainFields: ['module', 'main']

}

};