TinyExpr is a very small recursive descent parser and evaluation engine for math expressions. It's handy when you want to add the ability to evaluation math expressions at runtime without adding a bunch of cruft to you project.

In addition to the standard math operators and precedence, TinyExpr also supports the standard C math functions and runtime binding of variables.

- C99 with no dependencies.

- Single source file and header file.

- Simple and fast.

- Implements standard operators precedence.

- Exposes standard C math functions (sin, sqrt, ln, etc.).

- Can add custom functions and variables easily.

- Can bind variables at eval-time.

- Released under the zlib license - free for nearly any use.

- Easy to use and integrate with your code

- Thread-safe, provided that your malloc is.

TinyExpr is self-contained in two files: tinyexpr.c and tinyexpr.h. To use

TinyExpr, simply add those two files to your project.

Here is a minimal example to evaluate an expression at runtime.

#include "tinyexpr.h"

printf("%f\n", te_interp("5*5", 0)); /* Prints 25. */TinyExpr defines only four functions:

double te_interp(const char *expression, int *error);

te_expr *te_compile(const char *expression, const te_variable *variables, int var_count, int *error);

double te_eval(const te_expr *expr);

void te_free(te_expr *expr); double te_interp(const char *expression, int *error);te_interp() takes an expression and immediately returns the result of it. If there

is a parse error, te_interp() returns NaN.

If the error pointer argument is not 0, then te_interp() will set *error to the position

of the parse error on failure, and set *error to 0 on success.

example usage:

int error;

double a = te_interp("(5+5)", 0); /* Returns 10. */

double b = te_interp("(5+5)", &error); /* Returns 10, error is set to 0. */

double c = te_interp("(5+5", &error); /* Returns NaN, error is set to 4. */ te_expr *te_compile(const char *expression, const te_variable *lookup, int lookup_len, int *error);

double te_eval(const te_expr *n);

void te_free(te_expr *n);Give te_compile() an expression with unbound variables and a list of

variable names and pointers. te_compile() will return a te_expr* which can

be evaluated later using te_eval(). On failure, te_compile() will return 0

and optionally set the passed in *error to the location of the parse error.

You may also compile expressions without variables by passing te_compile()'s second

and third arguments as 0.

Give te_eval() a te_expr* from te_compile(). te_eval() will evaluate the expression

using the current variable values.

After you're finished, make sure to call te_free().

example usage:

double x, y;

/* Store variable names and pointers. */

te_variable vars[] = {{"x", &x}, {"y", &y}};

int err;

/* Compile the expression with variables. */

te_expr *expr = te_compile("sqrt(x^2+y^2)", vars, 2, &err);

if (expr) {

x = 3; y = 4;

const double h1 = te_eval(expr); /* Returns 5. */

x = 5; y = 12;

const double h2 = te_eval(expr); /* Returns 13. */

te_free(expr);

} else {

printf("Parse error at %d\n", err);

}Here is a complete example that will evaluate an expression passed in from the command

line. It also does error checking and binds the variables x and y to 3 and 4, respectively.

#include "tinyexpr.h"

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

if (argc < 2) {

printf("Usage: example2 \"expression\"\n");

return 0;

}

const char *expression = argv[1];

printf("Evaluating:\n\t%s\n", expression);

/* This shows an example where the variables

* x and y are bound at eval-time. */

double x, y;

te_variable vars[] = {{"x", &x}, {"y", &y}};

/* This will compile the expression and check for errors. */

int err;

te_expr *n = te_compile(expression, vars, 2, &err);

if (n) {

/* The variables can be changed here, and eval can be called as many

* times as you like. This is fairly efficient because the parsing has

* already been done. */

x = 3; y = 4;

const double r = te_eval(n); printf("Result:\n\t%f\n", r);

te_free(n);

} else {

/* Show the user where the error is at. */

printf("\t%*s^\nError near here", err-1, "");

}

return 0;

}This produces the output:

$ example2 "sqrt(x^2+y2)"

Evaluating:

sqrt(x^2+y2)

^

Error near here

$ example2 "sqrt(x^2+y^2)"

Evaluating:

sqrt(x^2+y^2)

Result:

5.000000

TinyExpr can also call to custom functions implemented in C. Here is a short example:

double my_sum(double a, double b) {

/* Example C function that adds two numbers together. */

return a + b;

}

te_variable vars[] = {

{"mysum", my_sum, TE_FUNCTION2} /* TE_FUNCTION2 used because my_sum takes two arguments. */

};

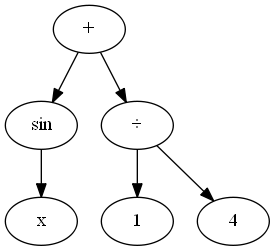

te_expr *n = te_compile("mysum(5, 6)", vars, 1, 0);te_compile() uses a simple recursive descent parser to compile your

expression into a syntax tree. For example, the expression "sin x + 1/4"

parses as:

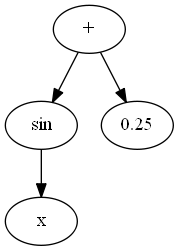

te_compile() also automatically prunes constant branches. In this example,

the compiled expression returned by te_compile() would become:

te_eval() will automatically load in any variables by their pointer, and then evaluate

and return the result of the expression.

te_free() should always be called when you're done with the compiled expression.

TinyExpr is pretty fast compared to C when the expression is short, when the

expression does hard calculations (e.g. exponentiation), and when some of the

work can be simplified by te_compile(). TinyExpr is slow compared to C when the

expression is long and involves only basic arithmetic.

Here is some example performance numbers taken from the included benchmark.c program:

| Expression | te_eval time | native C time | slowdown |

|---|---|---|---|

| sqrt(a^1.5+a^2.5) | 15,641 ms | 14,478 ms | 8% slower |

| a+5 | 765 ms | 563 ms | 36% slower |

| a+(5*2) | 765 ms | 563 ms | 36% slower |

| (a+5)*2 | 1422 ms | 563 ms | 153% slower |

| (1/(a+1)+2/(a+2)+3/(a+3)) | 5,516 ms | 1,266 ms | 336% slower |

TinyExpr parses the following grammar:

<list> = <expr> {"," <expr>}

<expr> = <term> {("+" | "-") <term>}

<term> = <factor> {("*" | "/" | "%") <factor>}

<factor> = <power> {"^" <power>}

<power> = {("-" | "+")} <base>

<base> = <constant>

| <variable>

| <function-0> {"(" ")"}

| <function-1> <power>

| <function-X> "(" <expr> {"," <expr>} ")"

| "(" <list> ")"

In addition, whitespace between tokens is ignored.

Valid variable names consist of a lower case letter followed by any combination of: lower case letters a through z, the digits 0 through 9, and underscore. Constants can be integers, decimal numbers, or in scientific notation (e.g. 1e3 for 1000). A leading zero is not required (e.g. .5 for 0.5)

TinyExpr supports addition (+), subtraction/negation (-), multiplication (*), division (/), exponentiation (^) and modulus (%) with the normal operator precedence (the one exception being that exponentiation is evaluated left-to-right, but this can be changed - see below).

The following C math functions are also supported:

- abs (calls to fabs), acos, asin, atan, atan2, ceil, cos, cosh, exp, floor, ln (calls to log), log (calls to log10 by default, see below), log10, pow, sin, sinh, sqrt, tan, tanh

The following functions are also built-in and provided by TinyExpr:

- fac (factorials e.g.

fac 5== 120) - ncr (combinations e.g.

ncr(6,2)== 15) - npr (permutations e.g.

npr(6,2)== 30)

Also, the following constants are available:

pi,e

By default, TinyExpr does exponentiation from left to right. For example:

a^b^c == (a^b)^c and -a^b == (-a)^b

This is by design. It's the way that spreadsheets do it (e.g. Excel, Google Sheets).

If you would rather have exponentiation work from right to left, you need to

define TE_POW_FROM_RIGHT when compiling tinyexpr.c. There is a

commented-out define near the top of that file. With this option enabled, the

behaviour is:

a^b^c == a^(b^c) and -a^b == -(a^b)

That will match how many scripting languages do it (e.g. Python, Ruby).

Also, if you'd like log to default to the natural log instead of log10,

then you can define TE_NAT_LOG.

-

All functions/types start with the letters te.

-

To allow constant optimization, surround constant expressions in parentheses. For example "x+(1+5)" will evaluate the "(1+5)" expression at compile time and compile the entire expression as "x+6", saving a runtime calculation. The parentheses are important, because TinyExpr will not change the order of evaluation. If you instead compiled "x+1+5" TinyExpr will insist that "1" is added to "x" first, and "5" is added the result second.