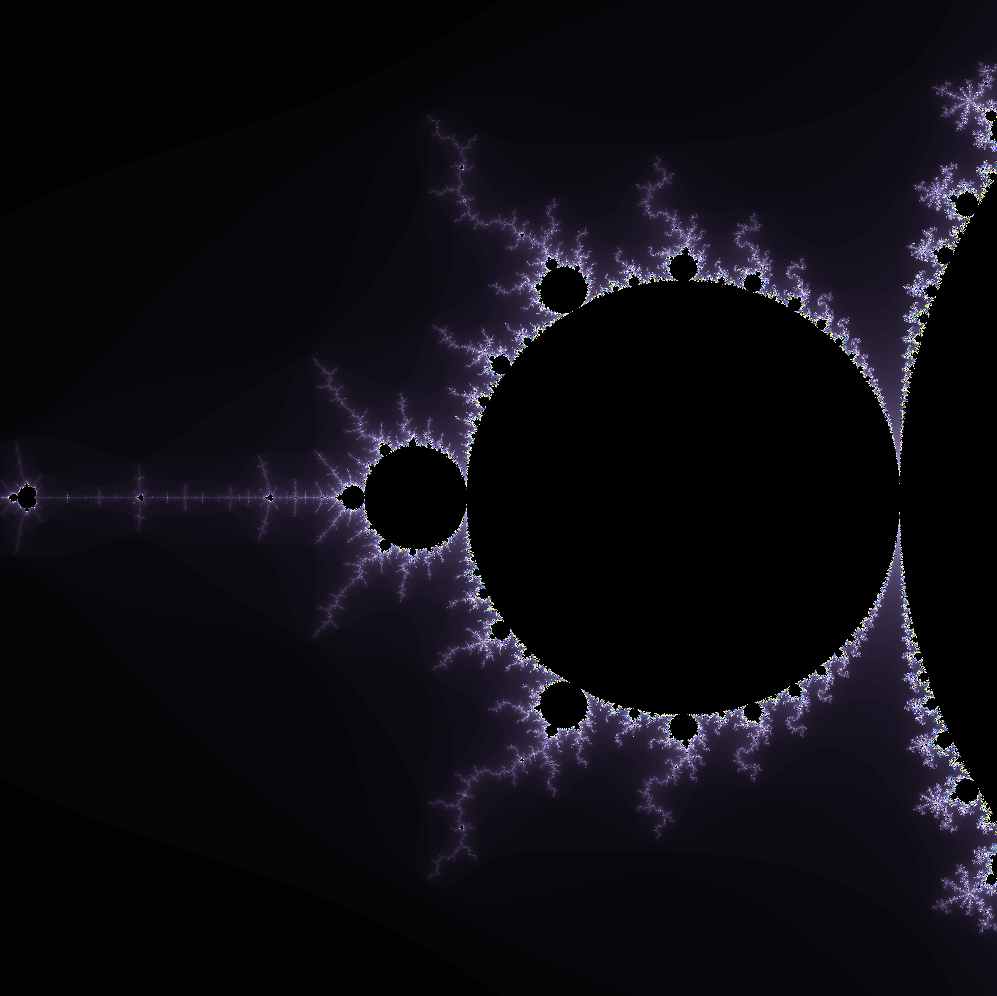

A project creating a Fractal exploration program.

A fractal has self-similarity:

- The property of an object which looks the same whatever the scale (no matter how big or how small they are).

- E.g. the snowflake, Romanesco Broccoli, pine cones, succulents, tree branches, foam.

- This project was challenging, though enjoyable to complete, and the end result is so worth it!

- I completed the mandatory and 4/5 of the bonus (everything except the third fractal). Note: The zoom centering the cursor is not perfect - please share if you figure it out!

- The versions included are /linux /macos_commented and /norminette

- Here is the outline of how I tackled fract-ol:

- Step 1: Learn the MiniLibX graphical library

- Step 2: Learn the Complex numbers notion

- Step 3: Learn how Fractals work

- Step 4: Learn about Event handling in the context of the project

- Step 5: Plan the structure of directories and files

- Step 6: Implement fract-ol

- Step 7: Test fract-ol against the evaluation checklist

- I worked with Linux, and once the program functioned, I translated the code to work on MacOS. See notes here: Differences between Linux and MacOS (though it might not make sense before delving in to the project's implementation).

- See references for resources used

Rendering requirements:

- The Mandelbrot and Julia fractal sets

- Mouse wheel zooms in/out. For Bonus, the zoom follows the mouse position

- Julia: can create different sets by passing different parameters to the ./fractol arguments

- If no parameters are provided, display a list of parameter options before a clean exit

- Use atlease three colours

- Bonus: move the view with arrow keys

- Bonus: Make the colours shift

Graphic management:

- Smooth window management

- Pressing ESC or clicking X on the window, closes the window and clean exit

- Must use images of the MiniLibX

Getting to know the basics of this graphical library with no prior knowledge can be overwhelming (atleast for me). It made more sense the more I wrote and tested our code for fractol, and in the end, it wasn't so intimidating. My big take is, it's a basic graphics library, with basic functions, and it's got nothing on you! Below is the sequence of the functions I learned:

- mlx_init()

- mlx_new_window()

- mlx_destroy_window()

- mlx_destroy_display()

- mlx_new_image()

- mlx_destroy_image()

- mlx_get_data_addr()

- mlx_pixel_put()

- mlx_put_image_to_window()

- mlx_hook()

- mlx_loop()

🔸 mlx_init()

- Initiates our program by establising a connection to the MLX graphical system.

- This is important for our program to be able to access to the resources needed for graphics rendering.

- In the context of fractol, we will have a data structure, which will contain an element e.g.

void *mlx_connect;- It stores the pointer returned from the mlx_init() function that makes the connection to the MLX system.

- Now that we have a connection established, and one that is unique to our program, the pointer to this connection will be taken as a parameter for many minilibx functions.

🔸 mlx_new_window()

- Is responsible for creating a window for our program. I imagine this as like, creating a blank canvas and frame before we can paint on it.

- We can define for it, its WIDTH and HEIGHT dimensions, and a window name, and it'll display it accordingly.

- In the context of fractol, our data structure will contain an element e.g.

void *window;- It stores the pointer returned from mlx_new_window() after having created a window for us.

- Similarly to the *mlx_connect pointer, the *window pointer will also be taken as a paramenter for each function that interacts with the window.

🔸 mlx_destroy_window()

- Is used to close, and destroy a window that has not been created successfully.

- It frees up any memory needed and clears the relevant resources accociated with the attempted window creation.

🔸 mlx_destroy_display()

- Is used to close a window. The difference from mlx_destroy_window() is that it doesn't free up and release resources.

- I used this function when working with Linux, but after working on MacOS, I realised it isn't necessary, and I could just use the mlx_destroy_window in its place.

- The minilibx MacOS version does not have the mlx_destroy_display() defined.

🔸 mlx_new_image()

- Creates a new image.

- At first I was confused with what the difference was between this function, and the mlx_new_window, because you could draw pixels on either image, or window.

- The difference is, this image acts like a buffer. We're drawing pixels on a image in memory, whereas, without this image, we're drawing pixels directly on the window.

- I imagine the image as like, a "draft canvas" - a seperate canvas to paint on, and once we're happy with it, we place the whole painting on top of our window as a final product.

- In the context of fractol, we want to draw our fractal on a buffer image first, off screen, before we display it on our window for the user to see.

- This is important, because, without a buffer, drawing one pixel at a time directly on the window can be visibly distracting and slow, and the user will see this in "real time" rather than seeing a completed drawing at once.

- Our data structure will contain an element e.g.

void *img;- It stores the pointer returned from mlx_new_image() after having created an image for us.

- The image buffer will be of the same WIDTH and HEIGHT dimension as our window.

🔸 mlx_destroy_image()

- If the new image creation is unsuccessfull, this function is used to destroy it and free memory associated with it.

🔸 mlx_get_data_addr()

- If the new image creation is successfull, this function retrieves information about the newly created image, and updates the relevent data elements of our data structure for fractol:

char *img_addr;stores the address of the imageint img_bpp;stores the number of bits per pixel in the imageint img_line;stores the size of each row in bytesint img_endian;stores information about the endianness of the image data- As long as we define the data elements for the image address, bpp, line, and endian in our struct, we don't really need to mind the endian data - minilibx will take care of it.

🔸 mlx_pixel_put()

- Is responsible for drawing a pixel directly on the window.

- Recall, we said that drawing pixels directly on the window is inefficient, and extremely slow. It invloves sending a request to the X server (Windows) or the WindowServer (MacOS) for each pixel, which can result in significant overhead.

- For this reason, we create our own pixel_put() function that can update all the pixel data via a buffer before displaying the entire updated image in a single operation with

mlx_put_image_to_window(). - For our fractol, we will create our own pixel_put function called

ft_pixel_put- It calculates where we want each pixel to be placed on our image (buffer), and colours it.

🔸 mlx_put_image_to_window()

- After our ft_pixel_put() function has set all the data for all the pixels of our image, this function renders and displays our image on the window, our final "canvas".

🔸 mlx_hook()

- Is responsible for handling key and mouse events, used to interact with our window.

- It takes in as parameters:

- the pointer to our window

- an int code for the event, for example:

- the code for a key event is

KeyPressfor Linux and2for MacOS - the code for a mouse event is

ButtonPressfor Linux and4for MacOS - the code for a close (ESC or X) event is

DestroyNotifyfor Linux and17for MacOS

- the code for a key event is

- an int code for the event mask, which captures the specific event types, for example:

- the event mask for a key event is

KeyPressMaskfor Linux - the event mask for a mouse event is

ButtonPressMaskfor Linux - the event mask for a close (ESC or X) event is

StructureNotifyMaskfor Linux - MacOS doesn't use this parameter, so we can set it to 0.

- the event mask for a key event is

- a user-defined function to handle a specific event type, e.g.

handle_key()handle_mouse()clean_exit()

- a pointer to our data structure

🔸 mlx_loop()

- keeps the application running and responsive, as without it, our program would finish executing without capturing user input events like keyboard presses, or mouse movements. It would simply execute the code that sets up the window and be non-interactive.

-

The "complex plane" is a mathematical concept used in complex number theory and fractal geometry.

-

It's a two-dimensional plane where each point represents a complex number.

-

The complex plane has two axes:

- the horizontal axis, often denoted as the real axis

- and the vertical axis, often denoted as the imaginary axis

-

Complex numbers are represented in the form

x + yi- where the "x" component is represented by the real axis

- and the "y" component is represented by the imaginary axis

-

In the context of our program, we define in our data structure the following elements:

double cmplx_r;which stores a floating-point number representing the real component of a complex valuedouble cmplx_i;which stores a floating-point number representing the imaginary component of a complex value- These will be important for our fractal mathematical formulas

-

In the context of fractals like the Mandelbrot set and Julia sets, the points in the complex plane are iteratively computed to determine if they are within certain boundaries, and this information is used to generate fractal images.

- By "iteration", we mean repeated application of a mathematical formula, which differs between diferent fractal sets.

🔸 Fractal set formulas

-

Both the mandelbrot and julia fractals share the same mathematical formula:

z = z^2 + c -

How the sets appear different from each other lies in the way they handle the complex numbers (z) and constants (c)

-

Mandelbrot set:

- explores the behavior of sequences for different c (constant) values

- where z is the complex number being iterated

-

Julia set:

- explores the behavior of sequences starting from different initial z (complex) values

- where c is a fixed constant remaining the same for all points

- this is why, changing the c constant values will generate varying patterns of the julia set

🔸 Iterations

- Recall, fractals are generated through iterative processes and mathematical equations.

- In its first iteration, the fractal shape would be a point on the complex plane.

- For each subsequent and repetative iteration, the mathematical equation generates a new set of points on the complex plane.

- In our data structure, we will have an element e.g.

int iterations;- I have this data field set at 100. This means, at the first launch of the program, it would have rendered an image worth 100 iterations. This gives us a clear image of the fractal shape.

- The lesser the number of iterations, the less "distinguished" the fractal shape will appear to us, which makes sense because, say, if we'd only done 10 iterations, fewer "points" of the fractal set have been generated and "drawn".

🔸 Escape criteria

-

The escape criteria is a set of conditions used to determine whether a point of the fractal should "escape" from further iterations.

-

These conditions distinguish between points that belong within a fractal set, and points that are outside the boundary of a fractal (non-fractal set points).

-

Distinguishing set and non-set points are important for a number of reasons:

- Iterations can be finite. An escape condition prevents thhis.

- We're able to control and adjust the colours and shading of pixels in the final fractal image, that sets apart the fractal, and its boundary.

-

Checking the Escape Criteria:

- After each iteration, we calculate the hypotenuse or the distance of the complex number "z" from the origin (0,0) in the complex plane.

- In our data structure, we will have the element e.g.

double hypoteneuse;- It will store a calculated number used to check whether a point on the complex plane has escaped the fractal set.

- The hypotenuse is calculated using the Pythagorean theorem:

-

PYTHAGOREAN THEOREM:

- In a right triangle (a triangle with one angle of 90 degrees), the square of the length of the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) is equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the other two sides. E.g.:

- Where "a" and "b" be the lengths of the two shorter sides (the legs)

- Where "c" be the length of the hypotenuse

- The theorem states that:

a^2 + b^2 = c^2

- In a right triangle (a triangle with one angle of 90 degrees), the square of the length of the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) is equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the other two sides. E.g.:

- Recall earlier, we talked about event handling, and creating user-defined functions that handle specific key, mouse, or close events.

- In our handler functions is where we can assign or "hook" a specific key, to an action or how we want the window/image to interact. For example, we say:

- If the key

ESC(or53in AppleScript) is pressed, we want the window to exit/close - Or, if the key

Left arrow(or123in AppleScript) is pressed, we want to fractal image to shift to the left. - Or, if the mouse button is

4(scrolls up), we want to fractal image to zoom in. - And so on, so forth.

- If the key

- In our data structure, we will define the elements e.g.

double shift_r;which stores the horizontal translation in the complex plane, used to shift the fractal left or rightdouble shift_i;which stores the vertical translation in the complex plane, used to shift the fractal up or downdouble zoom;which stores the zoom ratio of the fractal image, determining how much the fractal is magnified or reduced in size.

fractol/

│

├── Makefile

│

├── libft/

│

├── minilibx-macos/

|

├── inc/

│ └── fractol.h

│

└── src/

├── fractol.c

├── events.c

├── init.c

├── colours.c

├── render.c

└── utils.c

- Now that we have a rough idea of the functions we need to render an image, let's write some pseudocode to help us start implementing our code.

Pseudocode:

//Define a program that will launch a window and display a fractal for exploration

//Handle argument inputs and argument errors

//Handle input for mandelbrot

//Handle input for julia which requires an extra two arguments for its complex values

//Initialise the fractal by

//Setting the relevant data structure elements, its data

//Establishinhg a connection for our profgram, to the MLX graphical system

//Creating a window (our blank frame and canvas)

//Creating an image (our draft canvas to work on before displaying the final image on our window)

//Handle the user interactions by setting up our event hooks

//Handle key press events

//Handle mouse click/scroll events

//Handle window closing and exit events

//Render our fractal image and display it on the window

//Get our image data, e.g. its coordinates and colours, for every single pixel, in every row and every column of our complex map

//Display the pixels on our window

//Until the program is closed, make sure it's in a state of continous waiting for the user's interactions, e.g. key press or mouse clicks

- MiniLibx libraries:

- For M, I went with OpenGL version

- Download it from the project page on your intra, unzip the file then place the directory at the root of your repository.

- When compiling your fractol, there will be warnings shown on the console relating to the MiniLibx - don't mind this.

- At the root of your repository, do:

<project/directories> to only check norm errors in your source files, e.g.

norminette inc/ src/

- MiniLibx functions:

- L uses

mlx_destroy_window()andmlx_destroy_display() - M uses the one

mlx_destroy_window() mlx_hook()is handled differently between L and M

- L uses

- Keypress codes:

- M uses Applescript key codes, different to that of L

- Makefile linker flags:

- L uses

-lXext -lX11 - M uses

-Lminilibx-macos -lmlx -framework OpenGL -framework AppKit - In my Makefile, I wrote it in a way that it could detect between Linux and MacOS, and compile accordingly. This seemed a great idea at first (and now I've learned something new), it was redundant because, of the differences in codes and functions mentioned above. There would surely be a way to remedy this, to write code that works universally.

- L uses

- Getting started with MiniLibX:

- MiniLibX Tutorial:

- Fractal Tutorial, great explanation of the complex notion:

- Julia set values:

- Colour interpolation:

- Evaluation guides: