Git is a version control system. It helps you organize projects in a way that lets you to:

- break your work up into manageable pieces

- modify the same files as several other people

- try multiple approaches without having to make backups

- reliably undo changes that don't work

- store your project remotely and transfer it to other machines

- work on your project locally even without access to your remote copy

and more! These features by themselves motivate the majority of programmers to use Git even if they are working on a solo project. Moreover, larger teams simply would not be able to function without version control.

Coming from no version control entirely, it may seem daunting to have to remember all of these Git commands. The goal of this workshop is to give you a handful of commands that will most of your day-to-day Git usage, and to show you some of the benefits along the way.

Let's begin.

- Windows: Download from https://git-scm.com/download/win

- OS X: Download from https://git-scm.com/download/mac OR

install Homebrew http://brew.sh/ and run

$ brew install gitOR simply run$ gitand you will be prompted to install Xcode Command Line Tools, which includes Git. - Linux:

$ yum install giton Fedora or$ apt-get install giton Debian-based distributions.

You need to introduce yourself to Git so that it can attribute code contributions to you. Run

$ git config --global user.name "Your Name"

and

$ git config --global user.email your@email.com

Doing this doesn't sign you up for anything and you won't get emails because of it. It simply sets two variables in a global configuration file on your computer for later use.

Login at https://github.com/ and make a new repository with the button on the rightmost column. Make sure to check the box for initializing the repository with a README. Right now the repository only lives on GitHub's remote servers. To get it onto your local machine, go to the directory you would like the project to be placed in and run

$ git clone <url of your github repository>

This will make a new directory that contains the project you have just cloned. Go into that directory and run

$ git status

which should print

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

nothing to commit, working directory clean

Congratulations, you've just created and cloned your first Git repository.

Let's give Git some changes to track.

Using your favorite editor, write Hello World in line 3 of the README file.

If you run $ git status you will see something like

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: README.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Run

$ git add README.md

to stage the README file.

Once changes have been staged, we can commit them to the local repository with

$ git commit -m "Add Hello World to README"

The -m flag signals that the string in double quotes following it is the commit message,

a short description of the changes in the commit.

Finally, to get your changes back onto GitHub, simply run

$ git push

You've made it through your first iteration of the edit-stage-commit-push cycle that is core to Git!

Find somebody near you and introduce yourselves! We will now simulate collaborating on a project.

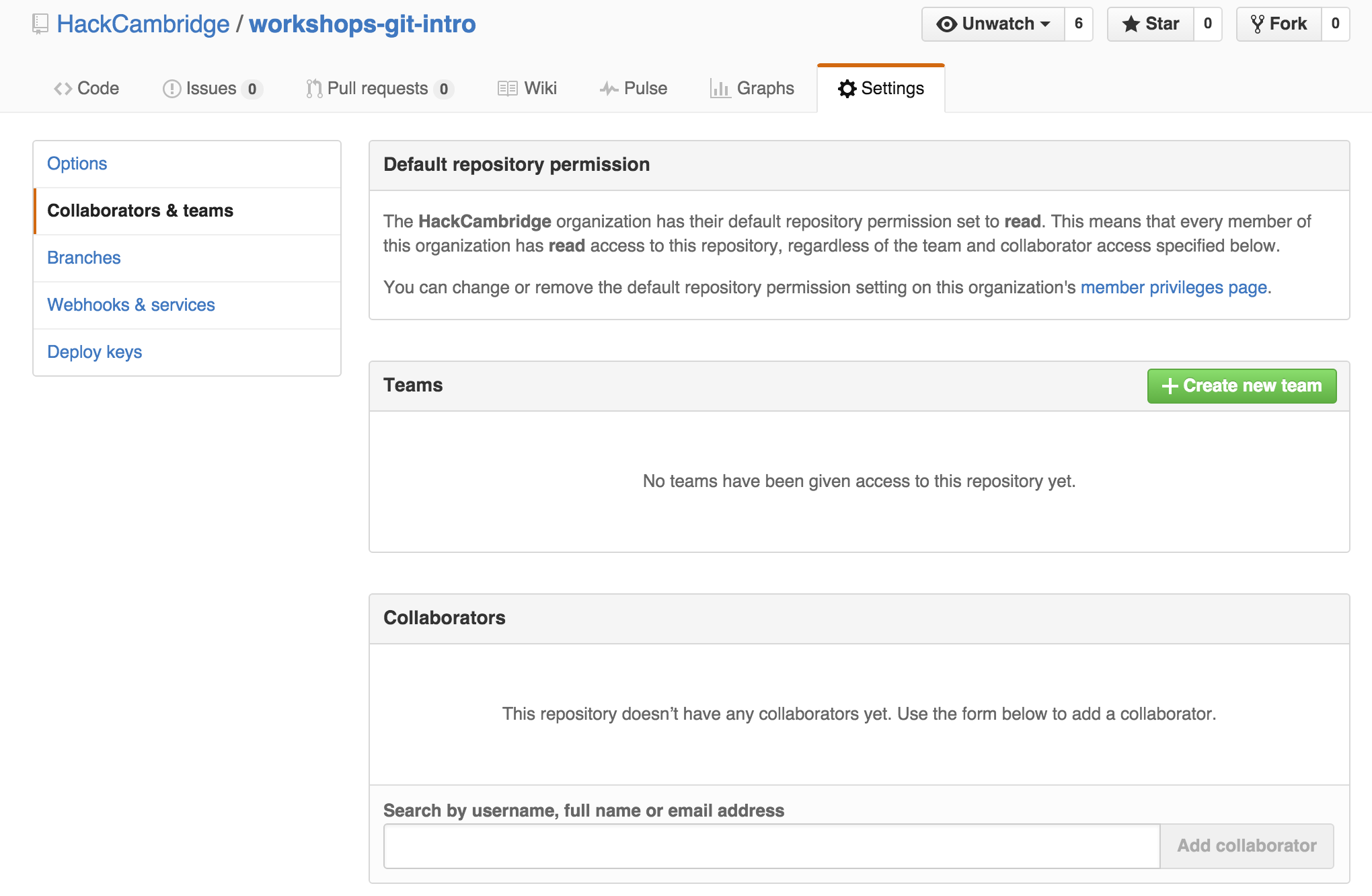

First, one person in each pair should add the other as a collaborator to the GitHub repository from earlier.

If you were the one added, make sure you clone that repository.

If you were the one added, make sure you clone that repository.

Next, each person should make a branch that is named with your own name in the shared repositories by using

$ git branch <your name>

That creates the branch, but if you run $ git branch you will find that you are still on the master branch.

To move to a different branch, run

$ git checkout <branch name>

In the future, this can be accomplished in one go with $ git checkout -b <branch name>, but it is important

to be aware of Git's branch management commands under git branch.

Once you've successfully moved to your new branch, write contributors: <your name> in the 4th line of the

README and then add-commit-push your changes to GitHub.

When you tried to push, you probably ran into this error

fatal: The current branch test has no upstream branch.

To push the current branch and set the remote as upstream, use

git push --set-upstream origin <branch name>

This is because your new branch doesn't exist in the remote repository yet. Git is very helpful in that it knows some common things that people try do to while using it, such as push a new branch. In these cases, the output will tell you the correct command to run. Follow Git's advice and run

$ git push --set-upstream origin <branch name>

The owner of the repository should then pull the changes (partner, look over their shoulder while they do this)

$ git pull

You'll notice that your partner's branch has been pulled to your local repository. To finalize these changes, first checkout your partner's branch. This is necessary because no reference for your partner's branch exists locally until you check it out, even though the changes themselves have already been fetched to your local machine. Then, checkout master and run

$ git merge <branch name>

for both you and your partner's branches.

The second time you merge, you will get a merge conflict since both you and your partner have edited the same line. The areas where the two branches conflict are marked out like so:

<<<<<<< HEAD

contributors: foo

=======

contributors: bar

>>>>>>> bar

You will not be able to merge until all structures like this are resolved in the code. In this case, you're both collaborators so resolve the merge conflict by listing both of your names in the collaborators lines.

Once you have finished resolving, add-commit-push again. If you were not the one doing the merging,

you should $ git pull to receive the changes in your local repository.

Feel free to spend some extra time making new branches, committing things, and merging back and forth!

You've worked through the exercises in this workshop. Try now to do some more complicated tasks, aided by the information below. Our demonstrators will be on hand to answer any questions you have.

A good task will be to try and move some of your existing projects to Git and also GitHub.

Generally you should commit when you have implemented a small feature in your project. Your commit messages should be able to tell readers what was accomplished in your commit in less than 80 characters. If you really need to add more information, you can do so in a multi-line commit:

$ git commit -m "First line should be less than 80 char

Subsequent lines add information"

or simply run $ git commit which will open up your editor. The first line should contain all the information necessary

to tell readers what that commit accomplishes! If you find that it cannot, you have probably included too many

changes in your commit.

Some examples of things that are good commits:

- Implemented a method.

- Wrote an interface.

- Refactored a method.

- Renamed a class, method, or function. Bad commits:

- An entire fully implemented class (too large).

- Incomplete code, especially syntax mistakes.

- Single typo or stylistic fixes (too small).

- Changes for multiple unrelated features.

Whenever you would like to work on a new major feature, such as a new class or a refactor, make a branch with a descriptive name such as "classifier-implementation" or "migrating-to-sql". Depending on how many people are working on the project, it may be useful to include your name in the branch name as well.

Never push to master. Even when working by yourself on a project, it is good practice to make branches for features and to merge into master only when the feature has been fully implemented, tested, and reviewed.

After implementing and testing, you should submit your code for review by somebody from your team via a pull request, which is a proposal to merge one branch into another. Once the owner of the branch or repository, and ideally a few more people, look at your code for style and conformity to project guidelines, the pull request can be approved, in which case GitHub will merge the branches.

You can read more about the process here: https://guides.github.com/introduction/flow/ While this process seems tedious, it is universally adopted by top software companies to ensure quality of code. If a company actually skips code review, definitely think twice about working there.

You want your repo to be as system-agnostic as possible to allow anyone to clone it and do a bit of setup to start running with the project. For this reason, you should leave out

- any files that are specific to your operating system,

- any files that pertain to a specific workspace or IDE (Java IDEs are very good at doing this)

- any sensitive information such as database passwords

- binary files (images are a common exception)

- anything that can be easily re-generated from your codebase (like binary files or packages from a package manager)

This may require some changes to your project if you have some of this information hard-coded with other files that are important. This may be a time to look into general config files or environment variables to make your project more comfortably work on other systems.

To make this more manageable, check out the .gitignore file below.

If you're writing a commit with lots of changes, you would spend far too much time adding all of these files manually. Git commands support file "globbing", so instead of writing this:

git add assets/main.css

git add assets/normalize.css

git add assets/home.css

git add assets/video.css

You can write

git add assets/*.css

To add every .css file in the assets directory that has been changed. This extends

powerfully to the common statement

git add .

Which will add everything in your working directory that has been changed. What are the potential problems with this?

When adding lots of files to git, there are files that for some reason or another, you will never want committed (see above). If you try to remember these files manually, you will most likely forget. Why not let git know what files you don't want committed?

Simply create a .gitignore file at the root of your repository and list the files/folders you want to exclude

# Exclude any file with type .o

*.o

# Exclude a directory

annoying-ide-config/

# Exclude something only at the root

/config.json

/packages/

Now if we add a file config.json, and try git add ., nothing will be staged because Git knows to ignore that file.

The syntax can get quite complex and when it comes to un-ignoring something that has been ignored, can be slightly unintuitive.

Git works happily with other software. There are a lot of nice GUIs that you can use if looking at your repo visually will help. You may also find that your current editor of choice works with Git. The features can get quite fancy, allowing you to make commits and add files right inside the editor. The key feature, though, is to have a text editor that lets you easily see what files are changed. This will keep you much saner.