marginaleffects is an R package to compute and plot adjusted

predictions, marginal effects, contrasts, and marginal means for a

wide variety of models.

- What?

- Why?

- Getting started

- Vignettes:

- 63 supported classes of models

- Performance tips

- Case studies:

- Alternative software

- Technical notes

The marginaleffects package allows R users to compute and plot four

principal quantities of interest for 63 different classes of

models:

- Adjusted

Prediction

- The outcome predicted by a model for some combination of the regressors’ values, such as their observed values, their means, or factor levels (a.k.a. “reference grid”).

predictions(),plot_cap()

- Marginal

Effect

- A partial derivative (slope) of the regression equation with respect to a regressor of interest.

marginaleffects(),plot(),plot_cme()

- Contrast

- The difference between two adjusted predictions, calculated for meaningfully different regressor values (e.g., College graduates vs. Others).

comparisons()

- Marginal

Mean

- Adjusted predictions of a model, averaged across a “reference grid” of categorical predictors.

marginalmeans()

To calculate marginal effects we need to take derivatives of the regression equation. This can be challenging to do manually, especially when our models are non-linear, or when regressors are transformed or interacted. Computing the variance of a marginal effect is even more difficult.

The marginaleffects package hopes to do most of this hard work for

you.

Many R packages advertise their ability to compute “marginal effects.”

However, most of them do not actually compute marginal effects as

defined above. Instead, they compute “adjusted predictions” for

different regressor values, or differences in adjusted predictions

(i.e., “contrasts”). The rare packages that actually compute marginal

effects are typically limited in the model types they support, and in

the range of transformations they allow (interactions, polynomials,

etc.).

The main packages in the R ecosystem to compute marginal effects are

the trailblazing and powerful margins by Thomas J.

Leeper, and emmeans by

Russell V. Lenth and

contributors. The

marginaleffects package is essentially a clone of margins, with some

additional features from emmeans.

So why did I write a clone?

- Powerful: Marginal effects and contrasts can be computed for 63 different classes of models. Adjusted predictions and marginal means can be computed for about 100 model types.

- Extensible: Adding support for new models is very easy, often requiring less than 10 lines of new code. Please submit feature requests on Github.

- Fast: Computing unit-level standard errors can be orders of magnitude faster in large datasets.

- Efficient: Much smaller memory footprint.

- Valid: When possible, numerical results are checked against

alternative software like

Stata, or otherRpackages. - Beautiful:

ggplot2support for plotting (conditional) marginal effects and adjusted predictions. - Tidy: The results produced by

marginaleffectsfollow “tidy” principles. They are easy to program with and feed to other packages likemodelsummary. - Simple: All functions share a simple, unified, and well-documented interface.

- Thin: The package requires relatively few dependencies.

- Safe: User input is checked extensively before computation. When needed, functions fail gracefully with informative error messages.

- Active development

Downsides of marginaleffects include:

- No simulation-based inference.

- No multiplicity adjustments.

- No equivalence tests.

- Newer package with a smaller user base.

You can install the released version of marginaleffects from CRAN:

install.packages("marginaleffects")You can install the development version of marginaleffects from

Github:

remotes::install_github("vincentarelbundock/marginaleffects")First, we estimate a linear regression model with multiplicative interactions:

library(marginaleffects)

mod <- lm(mpg ~ hp * wt * am, data = mtcars)An “adjusted prediction” is the outcome predicted by a model for some combination of the regressors’ values, such as their observed values, their means, or factor levels (a.k.a. “reference grid”).

By default, the predictions() function returns adjusted predictions

for every value in original dataset:

predictions(mod) |> head()

#> rowid type predicted std.error conf.low conf.high mpg hp wt am

#> 1 1 response 22.48857 0.8841487 20.66378 24.31336 21.0 110 2.620 1

#> 2 2 response 20.80186 1.1942050 18.33714 23.26658 21.0 110 2.875 1

#> 3 3 response 25.26465 0.7085307 23.80232 26.72699 22.8 93 2.320 1

#> 4 4 response 20.25549 0.7044641 18.80155 21.70943 21.4 110 3.215 0

#> 5 5 response 16.99782 0.7118658 15.52860 18.46704 18.7 175 3.440 0

#> 6 6 response 19.66353 0.8753226 17.85696 21.47011 18.1 105 3.460 0The datagrid function gives us a powerful way to define a grid of

predictors.

All the variables not mentioned explicitly in datagrid() are fixed to

their mean or mode:

predictions(mod, newdata = datagrid(am = 0, wt = seq(2, 3, .2)))

#> rowid type predicted std.error conf.low conf.high hp am wt

#> 1 1 response 21.95621 2.0386301 17.74868 26.16373 146.6875 0 2.0

#> 2 2 response 21.42097 1.7699036 17.76807 25.07388 146.6875 0 2.2

#> 3 3 response 20.88574 1.5067373 17.77599 23.99549 146.6875 0 2.4

#> 4 4 response 20.35051 1.2526403 17.76518 22.93583 146.6875 0 2.6

#> 5 5 response 19.81527 1.0144509 17.72155 21.90900 146.6875 0 2.8

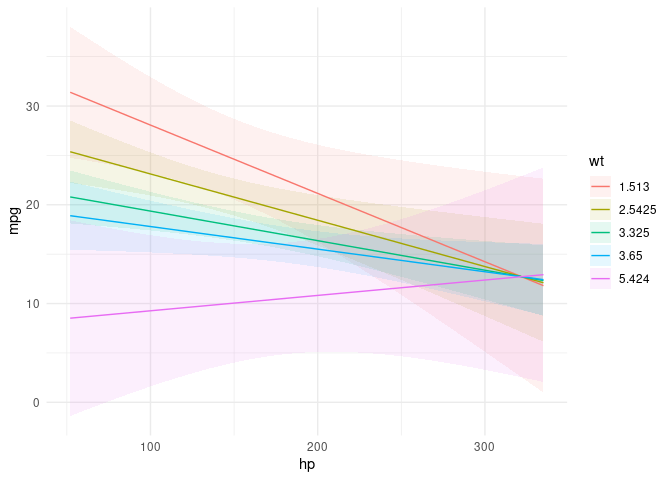

#> 6 6 response 19.28004 0.8063905 17.61573 20.94435 146.6875 0 3.0We can plot how predictions change for different values of one or more

variables – Conditional Adjusted Predictions – using the plot_cap

function:

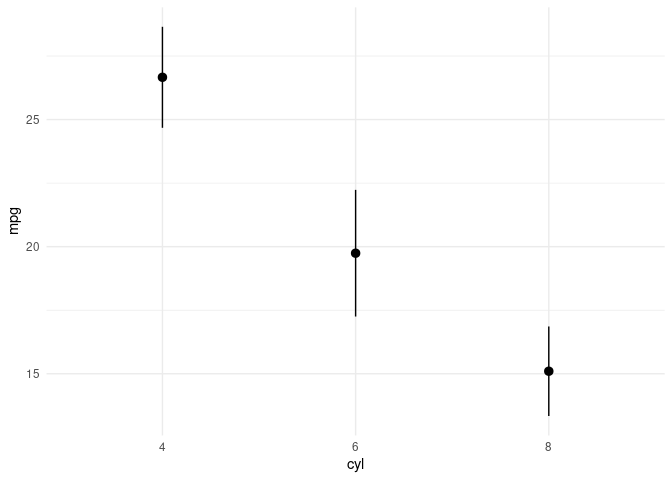

plot_cap(mod, condition = c("hp", "wt"))mod2 <- lm(mpg ~ factor(cyl), data = mtcars)

plot_cap(mod2, condition = "cyl")The Adjusted Predictions

vignette

shows how to use the predictions() and plot_cap() functions to

compute a wide variety of quantities of interest:

- Adjusted Predictions at User-Specified Values (aka Predictions at Representative Values)

- Adjusted Predictions at the Mean

- Average Predictions at the Mean

- Conditional Predictions

- Adjusted Predictions on different scales (e.g., link or response)

A contrast is the difference between two adjusted predictions, calculated for meaningfully different regressor values (e.g., College graduates vs. Others).

What happens to the predicted outcome when a numeric predictor increases by one unit, and logical variable flips from FALSE to TRUE, and a factor variable shifts from baseline?

titanic <- read.csv("https://vincentarelbundock.github.io/Rdatasets/csv/Stat2Data/Titanic.csv")

titanic$Woman <- titanic$Sex == "female"

mod3 <- glm(Survived ~ Woman + Age * PClass, data = titanic, family = binomial)

cmp <- comparisons(mod3)

summary(cmp)

#> Average contrasts

#> Term Contrast Effect Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|) 2.5 %

#> 1 Woman TRUE - FALSE 0.50329 0.031654 15.899 < 2.22e-16 0.441244

#> 2 Age (x + 1) - x -0.00558 0.001084 -5.147 2.6471e-07 -0.007705

#> 3 PClass 2nd - 1st -0.22603 0.043546 -5.191 2.0950e-07 -0.311383

#> 4 PClass 3rd - 1st -0.38397 0.041845 -9.176 < 2.22e-16 -0.465985

#> 97.5 %

#> 1 0.565327

#> 2 -0.003455

#> 3 -0.140686

#> 4 -0.301957

#>

#> Model type: glm

#> Prediction type: responseThe contrast above used a simple difference between adjusted

predictions. We can also used different functions to combine and

contrast predictions in different ways. For instance, researchers often

compute Adjusted Risk Ratios, which are ratios of predicted

probabilities. We can compute such ratios by applying a transformation

using the transform_pre argument. We can also present the results of

“interactions” between contrasts. What happens to the ratio of

predicted probabilities for survival when PClass changes between each

pair of factor levels (“pairwise”) and Age changes by 2 standard

deviations simultaneously:

cmp <- comparisons(

mod3,

transform_pre = "ratio",

variables = list(Age = "2sd", PClass = "pairwise"))

summary(cmp)

#> Average contrasts

#> Age PClass Effect Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|) 2.5 %

#> 1 (x + sd) / (x - sd) 1st / 1st 0.7043 0.05946 11.846 < 2.22e-16 0.5878

#> 2 (x + sd) / (x - sd) 2nd / 1st 0.3185 0.05566 5.723 1.0442e-08 0.2095

#> 3 (x + sd) / (x - sd) 3rd / 1st 0.2604 0.05308 4.907 9.2681e-07 0.1564

#> 4 (x + sd) / (x - sd) 2nd / 2nd 0.3926 0.08101 4.846 1.2588e-06 0.2338

#> 5 (x + sd) / (x - sd) 3rd / 2nd 0.3162 0.07023 4.503 6.7096e-06 0.1786

#> 6 (x + sd) / (x - sd) 3rd / 3rd 0.7053 0.20273 3.479 0.00050342 0.3079

#> 97.5 %

#> 1 0.8209

#> 2 0.4276

#> 3 0.3645

#> 4 0.5514

#> 5 0.4539

#> 6 1.1026

#>

#> Model type: glm

#> Prediction type: responseThe code above is explained in detail in the vignette on Transformations and Custom Contrasts.

The Contrasts

vignette

shows how to use the comparisons() function to compute a wide variety

of quantities of interest:

- Custom comparisons for:

- Numeric variables (e.g., 1 standard deviation, interquartile range, custom values)

- Factor or character

- Logical

- Contrast interactions

- Unit-level Contrasts

- Average Contrasts

- Group-Average Contrasts

- Contrasts at the Mean

- Contrasts Between Marginal Means

- Adjusted Risk Ratios

A “marginal effect” is a partial derivative (slope) of the regression

equation with respect to a regressor of interest. It is unit-specific

measure of association between a change in a regressor and a change in

the regressand. The marginaleffects() function uses numerical

derivatives to estimate the slope of the regression equation with

respect to each of the variables in the model (or contrasts for

categorical variables).

By default, marginaleffects() estimates the slope for each row of the

original dataset that was used to fit the model:

mfx <- marginaleffects(mod)

head(mfx, 4)

#> rowid type term dydx std.error statistic p.value conf.low

#> 1 1 response hp -0.03690556 0.01850168 -1.994714 0.046074078 -0.07316818

#> 2 2 response hp -0.02868936 0.01562783 -1.835787 0.066389187 -0.05931934

#> 3 3 response hp -0.04657166 0.02258719 -2.061862 0.039220870 -0.09084174

#> 4 4 response hp -0.04227128 0.01328278 -3.182411 0.001460543 -0.06830506

#> conf.high mpg hp wt am

#> 1 -0.0006429342 21.0 110 2.620 1

#> 2 0.0019406190 21.0 110 2.875 1

#> 3 -0.0023015909 22.8 93 2.320 1

#> 4 -0.0162375041 21.4 110 3.215 0The function summary calculates the “Average Marginal Effect,” that

is, the average of all unit-specific marginal effects:

summary(mfx)

#> Average marginal effects

#> Term Effect Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|) 2.5 % 97.5 %

#> 1 hp -0.03807 0.01279 -2.97730 0.00290798 -0.06314 -0.01301

#> 2 wt -3.93909 1.08596 -3.62728 0.00028642 -6.06754 -1.81065

#> 3 am -0.04811 1.85260 -0.02597 0.97928234 -3.67913 3.58292

#>

#> Model type: lm

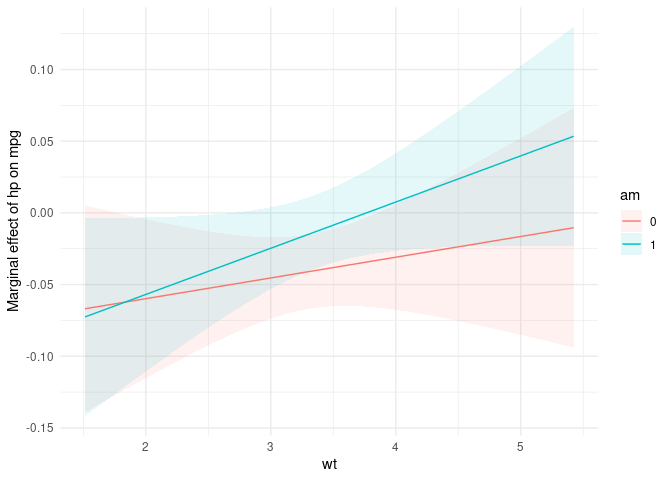

#> Prediction type: responseThe plot_cme plots “Conditional Marginal Effects,” that is, the

marginal effects estimated at different values of a regressor (often an

interaction):

plot_cme(mod, effect = "hp", condition = c("wt", "am"))The Marginal Effects

vignette

shows how to use the marginaleffects() function to compute a wide

variety of quantities of interest:

- Unit-level Marginal Effects

- Average Marginal Effects

- Group-Average Marginal Effects

- Marginal Effects at the Mean

- Marginal Effects Between Marginal Means

- Conditional Marginal Effects

- Tables and Plots

Marginal Means are the adjusted predictions of a model, averaged across a “reference grid” of categorical predictors. To compute marginal means, we first need to make sure that the categorical variables of our model are coded as such in the dataset:

dat <- mtcars

dat$am <- as.logical(dat$am)

dat$cyl <- as.factor(dat$cyl)Then, we estimate the model and call the marginalmeans function:

mod <- lm(mpg ~ am + cyl + hp, data = dat)

mm <- marginalmeans(mod)

summary(mm)

#> Estimated marginal means

#> Term Value Mean Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|) 2.5 % 97.5 %

#> 1 am FALSE 18.32 0.7854 23.33 < 2.22e-16 16.78 19.86

#> 2 am TRUE 22.48 0.8343 26.94 < 2.22e-16 20.84 24.11

#> 3 cyl 4 22.88 1.3566 16.87 < 2.22e-16 20.23 25.54

#> 4 cyl 6 18.96 1.0729 17.67 < 2.22e-16 16.86 21.06

#> 5 cyl 8 19.35 1.3771 14.05 < 2.22e-16 16.65 22.05

#>

#> Model type: lm

#> Prediction type: responseThe Marginal Means vignette offers more detail.

There is much more you can do with marginaleffects. Return to the

Table of

Contents

to read the vignettes, learn how to report marginal effects and means in

nice tables with the modelsummary

package, how to

define your own prediction “grid”, and much more.