An experimental tool to compare and flatten json-formatted logs for SIEM ingestion.

- Install Python 3.6+

Create your virtual environment and install dependencies.

$ git clone https://github.com/IntegralDefense/json-inspect.git

$ cd thisrepo

$ python3 -m venv venv

$ source venv/bin/activate

(venv) $ pip install -r requirements.txtHere's a step through of the logic for expirmenting with this module:

- When ingesting a new JSON-formatted log source, you usually have to configure transforms or filters in order to make the data searchable or indexable.

- Indexing and searching through JSON-formatted logs can get hairy quick if you have several tiers of nested logs or objects within a JSON-formatted log or event.

- One method of resolving this difficulty and/or increase SIEM effeciency is to flatten the logs by using transforms or filters.

- In order to flatten logs, you have to know what the log structure looks like and where it may need to be flattened.

- This becomes increasingly difficult with large volumes of logs.

- Understand how you can flatten logs for better SIEM performance/efficiency.

- Identify unique log formats / structures for transforms and filter development.

Json-inspect attempts to aid in this 'flattening' process by comparing logs based on their structure rather than their data. By using json-inspect you can more effeciently understand log structure so you can perform log flattening, like this:

// Before flattening:

{

ctime: "Thu Jan 17 13:43:57 2019",

device: "777-777-7777",

eventtype: "authentication",

factor: "Passkey",

host: "another2fa-host.local",

application: "EmailFederation",

ip: "10.7.0.5",

location: {

city: "Mortons Gap",

country: "US",

state: "Kentucky"

},

reason: "User approved",

result: "SUCCESS",

timestamp: 1546254864,

username: "Another2FAUser"

}

// After flattening

{

ctime: "Thu Jan 17 13:43:57 2019",

device: "777-777-7777",

eventtype: "authentication",

factor: "Passkey",

host: "another2fa-host.local",

application: "EmailFederation",

ip: "10.7.0.5",

city: "Mortons Gap",

country: "US",

state: "Kentucky",

reason: "User approved",

result: "SUCCESS",

timestamp: 1546254864,

username: "Another2FAUser"

}An example of flattening this log via a logstash filter would look something like this:

# flatten location

if [location] {

ruby { code => "event.get('location').each {|k, v| event.set(k, v) }" }

}Another use-case is when you run across dynamic keys within a JSON object. For example:

{

user: "Alfred",

hardtokens: {

hardtoken-yk-55555: {

platform: "yubikey",

totp_step: null

},

hardtoken-yk-555556: {

platform: "yubikey",

totp_step: null

}

}

}

// OR another example:

{

user: "Batman",

phones: {

iPhone1: {

number: "+1555555555",

os: "Some Apple iOS"

description: "Stays in the bat cave"

},

iPhone2: {

number: "+15555555556",

os: "Another Apple iOS",

description: "Stays in the bat mobile"

}

}

}In these cases, you have dynamic keys (iPhonex, hardtoken-yk-xxxxxx, etc.). You may have to flatten these logs by adding or converting these items into a list.

An example of how this could be accomplished with a logstash filter:

# create hardtokens list

if [hardtokens] {

ruby {

code => "

event.set('hardtokens_tmp', [])

event.get('hardtokens').each do |k,v|

event.set('hardtokens_tmp', event.get('hardtokens_tmp') + [ event.get(k) ])

end

"

}

}

# create phones list

if [phones] {

ruby {

code => "

event.set('phones_tmp', [])

event.get('phones_tmp').each do |k,v|

if v != nil

if v.key?('type')

event.set('phones_tmp', event.get('phones_tmp') + [ v['type'] + ': ' + v['number'])

else

event.set('phones_tmp', event.get('phones_tmp') + [ 'Unknown: ' + v['number'] ])

end

end

end

"

}

}When you are looking at a log source and trying to understand the strcuture, it is good to review the vendor documention or product documentation. However, we all know that one (or those many) vendors who's documentation is lacking.

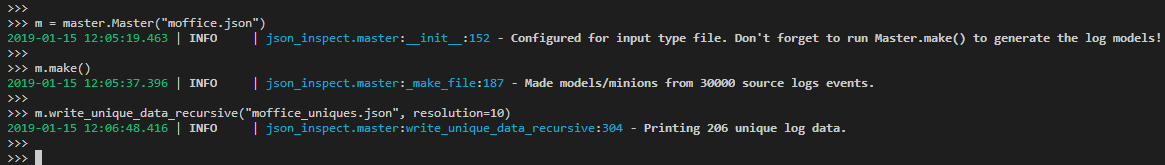

Json-inspect attempts to remedy this by giving you the ability to parse a large volume of logs and then output unique log formats. Here is an example when parsing a large volume of Office 365 Management API logs:

Notice that we modeled 30k logs and were able to narrow those down to only 206 logs that you need to be manually reviewed.

Also as part of this example, notice that we wrote the logs to file using the 'write_unique_data_recursive' function. This writes the actual data from each log structure that is identified as unique so that you can view an example of the raw log content as you build your transforms and filters.

Modeling logs refers to how json-inspect thinks about each log.

Json-inspect models logs by parsing JSON objects and then converting them to minion objects. As a minion, Json-inspect stores the data of the log values as well as a model of the data.

The model is helpful because we can use it to compare log structures of logs with varying content. We can also output the data by using the same minion if needed.

The following JSON data types do not change the structure of the log. The model will label these datatypes as edge so that when we compare the models, the labels will be equivalent:

- Integer

- String

- Bool

- Null

The following data types do change the structure of the log so their labels are set as 'DICT' and 'LIST' respectively:

- object/dictionary/hash table

- array/list

Note: In addition to the data types that do adjust log structure, we also want to compare dictionaries that may include differing keys.

If you converted [123, "my_string"] to a string and then hashed

it, the hash would be different than the hash for [456, "AnotherString"].

Using the labels from our log models, however, these two lists would be

converted to ["edge", "edge"] and would result in an equivalent

hash for both logs. This is essentially how we compare logs that

contain varying data.

To take it a step further, json-inspect models the above as ["edges_only"]

so that the hash stays the same whether you have two edges or forty-five.

It acts this way because having forty-five edges does not change the

structure of the log, only the quantity of items in the list.

Essentially, json-inspect gives each data set a common label. Then, it provides a way to hash the object, which is basically sorting keys and then convertin the object to a string. Once in string form, it is hashed.

And as you change the resolution in which you look at the model, the more specific you can get about how deeply you want to look for unique logs.

For example, take a look at these two logs:

{

"key1": "MyString",

"key2": 12345,

"key3": ["ListItem", 54321, {"NestedKey1": "NestedValue"}, true, null, ["InnerList","MoreInnerList"]],

"key4": {

"NestedKey2": "SomeValue"

}

}

// Log 2

{

"key1": "MyString",

"key2": 12345,

"key3": ["ListItem", 54321, "NotNestedValue", false, null, ["InnerList", "MoreInnerList"]],

"key4": {

"NestedKey2": "SomeValue"

}

}If you look at these logs with a resolution of zero, you would get the following:

from json_inspect import master

m = master.Master("reamde.json") # Set the file to be used

m.make() # Parse the logs and create the models

m.print_unique_models(resolution=0, indent=2)

# Output:

{

"7346da258c47dc6dcf2cf6184638c91f": {

"key1": "edge",

"key2": "edge",

"key3": "LIST",

"key4": "DICT"

}

}Notice a couple things:

- You are presented with the hash of the object at this resolution.

- There is only ONE model printed.

There is only one model printed because at the initial tier of the logs, they are both equivalent.

Now lets use a resolution of 1:

from json_inspect import master

m = master.Master("reamde.json") # Set the file to be used

m.make() # Parse the logs and create the models

m.print_unique_models(resolution=1, indent=2)

# Output:

{

"1a8a5c002dfec9aa58e65af353c969e4": {

"key1": "edge",

"key2": "edge",

"key3": [

"DICT(s)",

"LIST(s)",

"edge(s)"

],

"key4": "DICT_KEYS: ['NestedKey2']"

},

"14d538d29f4ea8d6ba2556a689bcd357": {

"key1": "edge",

"key2": "edge",

"key3": [

"LIST(s)",

"edge(s)"

],

"key4": "DICT_KEYS: ['NestedKey2']"

}

}Now, we see two separate hashes at this resolution. Note that at this resolution, the structure of the log does differ within the list that is the value for key3.

To model log data, json-inspect ingests each data value in a log into an object called a minion. A minion contains the following items (but not limited to):

- Data value it represents

- The label of the data type (edge, DICT, LIST, etc.)

- Child minions, like in the case of a dictionary or list.

An example log:

{

"key1": "value1",

"key2": {

"key3": 123

},

"key4": ["Hello"]

}To simplify, you can think of this JSON object being stored like this:

DictMinion(

label="DICT",

data={

"key1": EdgeMinion(label="edge", data="value1"),

"key2": DictMinion(

label="DICT",

data={"key3": EdgeMinion(label="edge", data=123)}

),

"key4": ListMinion(

label="LIST",

data=[EdgeMinion(label="edge", data="Hello")]

),

}Each Minion has a set of functions to display the label, data, or hash of the model.

To run the program, you create a master. The master api give you access to various functions to ingest logs and output the unique log structures and models.

- Master.print_unique_models(resolution=0, indent=None)

- Prints the model for the log based on resolution (how deep you want to represent the log). You can pretty print by using indent.

- Master.print_unique_data(resolution=0, indent=None)

- Prints the data for the log based on resolution specified.

- Master.write_unique_models(output_file, resolution=0, indent=None)

- Writes the models to file.

- Master.write_unique_data(output_file, resolution=0, indent=None)

- Writes the data to file.

- Master.write_unique_data_recursive(output_file, resolution=0, indent=None)

- Recursively starts at the resolution defined, notes unique log models, then subtracts 1 from the resoltuion and repeats until resolution == 0-. This gives you a thorough run through high-volume logs.

from json_inspect import master

m = master.Master(input_file="example_logs.json") # Set file to ingest.

m.make() # Parse logs and create models.

# These commands will step through the structure of the log model.

# These functions will help to identify where your logs can be

# flattened.

m.print_unique_models(resolution=0, indent=2)

# OUTPUT

{

"2444e6cb9505d17b89efb154f78a18ea": {

"age": "edge",

"assignment": "edge",

"name": "edge",

"previous_assignments": "LIST",

"rank": "edge",

"species": "edge"

},

"672ad685628256d29a5369ebefd059c1": {

"age": "edge",

"home_planet": "edge",

"name": "edge",

"specialties": "LIST",

"species": "edge"

}

}m.print_unique_models(resolution=1, indent=2)

# OUTPUT

{

"244c3e15aa13c51c0be4626610baf777": {

"age": "edge",

"assignment": "edge",

"name": "edge",

"previous_assignments": [

"DICT(s)"

],

"rank": "edge",

"species": "edge"

},

"91143518648e5077589680d948593883": {

"age": "edge",

"home_planet": "edge",

"name": "edge",

"specialties": [

"edges_only"

],

"species": "edge"

},

"998db1309e33d4ca6b6b4d0f65758857": {

"age": "edge",

"home_planet": "edge",

"name": "edge",

"specialties": [

"DICT(s)",

"edge(s)"

],

"species": "edge"

}

}m.print_unique_data (resolution=0, indent=2)

# OUTPUT

{

"2444e6cb9505d17b89efb154f78a18ea": {

"age": 43,

"assignment": "USS Titan",

"name": "William T. Riker",

"previous_assignments": "LIST",

"rank": "Captain",

"species": "human"

},

"672ad685628256d29a5369ebefd059c1": {

"age": 22,

"home_planet": "Tatooine",

"name": "Anakin Skywalker",

"specialties": "LIST",

"species": "human"

}

}m.print_unique_models(resolution=4, indent=2)

# OUTPUT

{

"cd894fcbc758efe21e2207fdb40e5a38": {

"age": 63,

"assignment": "USS Enterprise-E",

"name": "Jean-Luc Picard",

"previous_assignments": [

{

"assignment": "USS Reliant",

"rank": "Ensign"

},

{

"assignment": "USS Stargazer",

"rank": "Commanding Officer"

},

{

"assignment": "USS Enterprise-D",

"rank": "Commanding Officer"

}

],

"rank": "Captain",

"species": "human"

},

"d63b0a2a9c17362110eff29fb7c8d225": {

"age": 43,

"assignment": "USS Titan",

"name": "William T. Riker",

"previous_assignments": [

{

"assignment": "USS Pegasus",

"rank": "Ensign"

},

{

"assignment": "USS Potemkin",

"rank": "Lieutenant"

},

{

"assignment": "USS Hood",

"rank": "First Officer"

},

{

"assignment": "USS Enterprise-D",

"rank": "First Officer"

},

{

"assignment": "USS Enterprise-E",

"rank": "First Officer"

}

],

"rank": "Captain",

"species": "human"

},

"3cce4c3e9d51bf0f575a12c0955be489": {

"age": 22,

"home_planet": "Tatooine",

"name": "Anakin Skywalker",

"specialties": [

"Anger",

{

"alientating_companions": [

"edge(s)"

]

},

"Pod racing"

],

"species": "human"

}

}