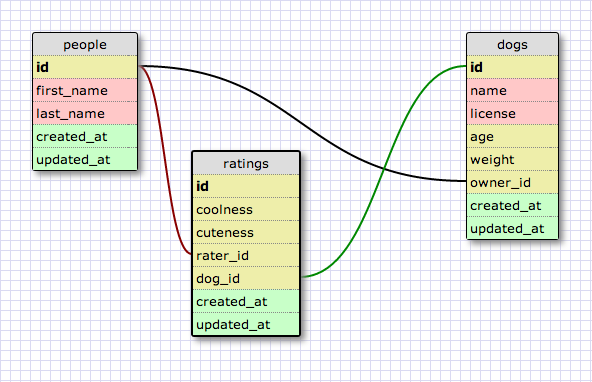

Figure 1. Database schema for this exercise.

In this exercise we'll create a database with the schema seen in Figure 1. We're going to begin using Active Record to create and update our database schema. We'll write Ruby, and Active Record will write the SQL for us.

Rather than writing SQL, we are going to write Active Record migrations. We'll write one migration for each change that we want to make to our database. We'll write a new migration file each time we want to add a table, add a column to an existing table, remove a column, rename a column, etc. Any change we make to our database will be written in its own migration file.

Why do we write migrations? Well imagine that you're a database administrator and one fine day a programmer asks you to make a change like add a NOT NULL or add a foreign key field. Where do you write this down? Is there a piece of code that records the change to the schema? Many large-scale organizations get around this by literally having a log book where the database admin writes down who requested what and why, who approved it and what the command was to enter it! What if, instead, you recorded that same transformation of the schema in a programming language? The transformation, or "migration" would live in git with a useful commit message, a date, etc. It would be a record of the transformation and, hopefully, the "undo" operation on that operation so it could be un-done. That's a good practice that Rails adopted and drove into the design of ActiveRecord.

Instead of writing raw SQL like:

CREATE TABLE dogs (

id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,

name VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL,

license VARCHAR NOT NULL,

age INTEGER,

weight INTEGER,

owner_id INTEGER

created_at DATETIME,

updated_at DATETIME

);Figure 2. SQL to create a dogs table based on Figure 1.

class CreateDogs < ActiveRecord::Migration[5.0]

def change

create_table :dogs do |t|

t.string :name, { null: false, limit: 50 }

t.string :license, { null: false }

t.integer :age

t.integer :weight

t.integer :owner_id

t.timestamps

end

end

endFigure 3. Active Record migration for creating a dogs table based on Figure 1.

To create the dogs table from Figure 1 in SQL, we would write code akin to what we see in Figure 2. But, now we'll want to write Active Record migrations to do this. An Active Record migration for creating this same dogs table is provided in the file db/migrate/20140901164300_create_dogs.rb, and its code can be seen in Figure 3.

In the migration, we define a class that inherits from the class ActiveRecord::Migration[5.0]—we get access to the behaviors necessary for working with the database through inheritance. Our class is named CreateDogs. The name of the class describes what this migration is doing; it creates the dogs table.

Then we define a #change method for our class. This method defines what changes we want to make to our database. What change will this migration make?

Inside the #change method, we call the create_table method and pass it (1) the name of the table we want to create, and (2) a block describing what to do with the table (i.e., which columns to add).

When the #create_table method executes the block, it will pass in a TableDefinition object. We can think of this object as the table being created. We're referencing it in our migration as t. As the block is executed, we take our table and we add a string-type column (i.e., VARCHAR) called name, we add a string-type column called license, we add an integer-type column called age, etc.

How are we adding these columns? We're calling the #string and #integer methods on the table object passed to the block. We also call the #timestamps method; this method adds two datetime-type columns to the table: one named created_at and one named updated_at. It's conventional to add these to our tables.

When we call the methods for adding columns to our table, the first argument we pass is the name of the column, (e.g., :name). We can optionally pass in a second argument, an options hash, which we do when adding the name and license columns. We can use these options to place constraints on our database—just as we could in SQL. For example, not allowing null values for particular columns.

In our migration we've set up our database to defend itself against bad data. We prevent records being added to the dogs table if the dog has no name or no license. We've also helped to conserve space in our database by limiting a dog's name to 50 characters. By default most databases allocate 256 characters for a string field, meaning 256 bytes are locked up for every dog. 256 bytes — so what? Think of how many dogs are registered in the city you live. That 256 bytes per dog could turn into gigabytes of space containing no useful information.

It is a mark of the best developers that they are always thinking about how to help the database defend itself from dirty data. Dirty data is hard to clean up and often requires taking a site offline. While programming-stack applications may come and go, databases tend to have a much longer service lifetime (databases from the 60's and 70's are still running in many businesses and most universities). We'll eventually learn about validating data in our application before even trying to save it to the database, but even with validations, database constraints are your first, strongest, and most reliable means of protection against dirty data.

-

The name of the migration file begins with a timestamp in the format YYYYMMDDHHMMSS:

20140901164300. This is important. Active Record uses these timestamps to keep track of the migrations that have already been run. Each migration will only be run once. -

The second half of the file name (i.e., after the timestamp) must match the name of the class written in the migration:

_create_dogs.rbandCreateDogs. -

The class defined in the migration inherits from the class

ActiveRecord::Migration[5.0]). This gives the class access to behaviors for updating the database—methods likecreate_table,add_column, etc. -

No id column is specified in the migration. An id column is created automatically—unless you specify not to. The id field is an autoincrementing integer field.

-

Rather than explicitly creating created_at and updated_at columns, there is a shortcut method for creating them:

#timestamps. -

Earlier we mentioned that migrations should be reversible. Migrations written with

#changealready have their "reverse" built-in. You may encounter older migrations that have aself.upand aself.downmethod. Theself.upmethod is the change andself.downis the reverse change. You may be amazed to think of this: every time you type a character, or bold a word in most word processors it stores the change and the anti-change. That's how Undo features work: they apply the last "counter-action" and toss it aside (an example of a Stack data structure).

$ bundle install

$ bundle exec rake db:create

Figure 4. Installing gems listed in Gemfile and creating the database.

In this exercise and many of the exercises we'll encounter going forward at Recode, we'll need to run through some setup before beginning to work through the exercise. We'll need to make sure that all the required gems are installed and then create the database that we'll be working with (see Figure 4).

In this exercise, we are supplied with an Active Record migration that will create a dogs table in our database (see file db/migrate/20140901164300_create_dogs.rb). We also have a spec file that tests whether or not our dogs table matches our expectations for column types and names (see file spec/schema/dogs_table_spec.rb).

$ bundle exec rspec spec/schema/dogs_table_spec.rb

Figure 5. Running the tests that describe the dogs table.

Run the tests for just the dogs table (see Figure 5). Looking at the output of the tests, we'll see that there's no dogs table in the database. And, it follows that the expected columns are not found.

$ bundle exec rake db:migrate

Figure 6. Executing the rake task for running the database migrations.

Now let's run the provided migration to create our dogs table (see Figure 6). After running the migration, we should run our tests again and see the tests for the dogs table pass.

Now we'll write migrations to create the remaining two tables from the schema design presented in Figure 1: the people table and the ratings table.

Spec files have been provided that describe the expectations for these two tables. At this point the tests for these tables fail, and we can run them to see the expectations for each table's column types and names.

$ bundle exec rake db:new_migration[create_people]

Figure 7. Executing the rake task for generating a migration to create the people table.

Let's make these tests pass. We'll start by working on the people table. We'll need to write a migration to create the people table with the appropriate columns. We can use the provided Rake task to generate the migration file for us; remember that the name of the migration should describe what it does to change the database (see Figure 7). After our migration is written, we need to run the migration.

The tests for the people table should all pass if the migration was written properly. If any of the tests for the people table fail, use the provided Rake task to rollback the database (db:rollback), correct the migration file, run the updated migrations, and run the specs again.

Once all the tests for the people table pass, repeat the same process for creating the ratings table. Once the entire test suite passes, submit your solution.

Moving forward through Recode, we'll rely on Active Record migrations to update the structure of our databases. We need to be comfortable working with them. Do we have any questions about creating tables through migrations? Do we understand the syntax in a migration? Do we understand how our migration classes (e.g., CreateDogs) inherit behaviors like #create_table.

In this exercise, we've focused on creating tables with a desired set of columns. We'll learn more about updating those tables in subsequent exercises.

Note: We're testing the structure of our database—which tables and columns are present. These are non-standard tests. We generally would not write such tests, but as we're just learning to write migrations, these tests are provided to give us feedback.